|

1. Parliamentary Institutions

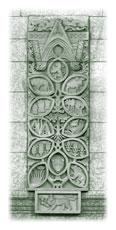

The Years Preceding Confederation Figure 1.1 Chronological Development of Canadian Parliamentary Institutions

Figure 1.2 Distribution of Senate Seats Figure 1.3 Distribution of Seats in the House of Commons

Separated from the British Isles by a three thousand mile ocean, situated next to the United States, living in a country which covers half of the North American continent, with our heterogeneous population, our two cultures and our two languages, we have developed a parliamentary practice of our own based on British principles and yet clearly Canadian. Arthur Beauchesne (Beauchesne, 4th ed., p. 8) The Parliament of Canada consists of the Crown, the Senate and the House of Commons. Canada’s Parliament was created by the Constitution Act, 1867,[1] a statute of the British Parliament[2] uniting the provinces of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick and Canada (Ontario and Quebec).[3] The legislation which gave birth to this new political confederation, to be known as the Dominion of Canada, was passed by Westminster[4] on March 29, 1867, and came into force on July 1 of that year. The Dominion’s first general elections were held later that summer and the House of Commons assembled at Ottawa for the first time on November 6, 1867. Members proceeded to elect James Cockburn as their Speaker[5] and the next day, November 7, the Dominion Parliament met to hear the Governor General, Lord Monck, read Canada’s inaugural Speech from the Throne.[6] While the law enacting Canada’s Parliament came into force on July 1, 1867, it would be misleading to conclude that Canadian parliamentary institutions were created at Confederation; they were then neither new nor untried. The provinces of Canada (Ontario and Quebec), Nova Scotia and New Brunswick each possessed sophisticated systems of governance, including legislative assemblies and upper houses, functioning according to historic, well‑understood principles of parliamentary law and practice. While these parliamentary traditions were largely British in origin, they had been adapted over the years as the local political situation required. This body of domestic practices, traditions, customs and conventions grew with the result that, at Confederation, Canada’s parliamentary system was well adapted to meet the needs of governing a young, diverse and growing nation.[7] The oldest of Canada’s institutional structures, those found in the Maritime Provinces, evolved out of the myriad instructions and commissions issued by the imperial government to successive governors over the years of British colonial rule.[8] By contrast, the institutional structure which emerged in the territory comprising present‑day Ontario and Quebec was from the beginning laid out in statutes, a practice continued at Confederation with the enactment of the Constitution Act, 1867 [1] Originally named the British North America Act, 1867, it was renamed the Constitution Act, 1867, in 1982 (Constitution Act, 1867, R.S. 1985, Appendix II, No. 5). For consistency, all references will be to its new title. [2] “From the earliest colonial times, the Parliament at Westminster had the power not only to make laws for the United Kingdom, but also to make laws for the overseas territories of the British Empire. In performing the latter function it was known as the imperial Parliament and its enactments were known as imperial statutes” (Hogg, P.W., Constitutional Law of Canada, 4th ed., Toronto: Carswell Thomson Professional Publishing, 1997, p. 44). [3] The Preamble of the Constitution begins with “Whereas the Provinces of Canada, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick have expressed their Desire to be federally united into One Dominion” and goes on to say, “And whereas such a Union would conduce to the Welfare of the Provinces” (Constitution Act, 1867, R.S. 1985, Appendix II, No. 5). [4] “A reference to the British Parliament, which is built on the site of Westminster Palace in London. Thus, references to ‘Westminster’ or ‘the Westminster model’ are references to the British Parliament and its practices” (McMenemy, J., The Language of Canadian Politics: A Guide to Important Terms and Concepts, 4th ed., Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2006, p. 406). [5] Journals, November 6, 1867, p. 2. For further information on the election of the Speaker, see Chapter 7, “The Speaker and Other Presiding Officers of the House”. [6] Journals, November 7, 1867, pp. 3‑4. For further information on the Speech from the Throne, see Chapter 15, “Special Debates”. [7] The following are some of the sources consulted on the evolution and function of Canadian parliamentary institutions: Bourinot, J.G., Parliamentary Procedure and Practice in the Dominion of Canada, 2nd ed., rev. and enlarged, Montreal: Dawson Brothers, Publishers, 1892; Bourinot, Sir J.G., 4th ed., edited by T.B. Flint, Toronto: Canada Law Book Company, 1916; Dawson, R.M., Dawson’s The Government of Canada, 6th ed., edited by N. Ward, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1987; Forsey, E.A., How Canadians Govern Themselves, 6th ed., Ottawa: Library of Parliament, 2005; Franks, C.E.S., The Parliament of Canada, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1987; Hogg, 4th ed.; Jackson, R.J. and Jackson, D., Politics in Canada: Culture, Institutions, Behaviour and Public Policy, 6th ed., Toronto: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2006; Mallory, J.R., The Structure of Canadian Government, rev. ed., Toronto: Gage Publishing Limited, 1984; McMenemy, 4th ed.; Stewart, J.B., The Canadian House of Commons: Procedure and Reform, Montreal and London: McGill‑Queen’s University Press, 1977; Van Loon, R.J. and Whittington, M.S., The Canadian Political System: Environment, Structure and Process, 4th ed., Toronto: McGraw‑Hill Ryerson Limited, 1987; Whittington, M.S. and Van Loon, R.J., Canadian Government and Politics: Institutions and Processes, Toronto: McGraw‑Hill Ryerson Limited, 1996; and Wilding, N. and Laundy, P., An Encyclopaedia of Parliament, 4th ed., London: Cassell & Company Ltd., 1972. [8] Murdoch, B., A History of Nova‑Scotia or Acadie, Vol. II, Halifax: James Barnes, Printer and Publisher, 1866, pp. 351‑4. |

|