RNNR Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

Creating A Fair And Equitable Canadian Energy Transformation

Introduction

In response to the threat of climate change, countries around the world are adopting measures to cut their greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and adapt their economies to lower‑emitting activities and technologies. Canada is no exception. Under the Paris Agreement (COP21), which has 194 signatories, Canada has committed to taking the necessary action to limit global warming to two degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, and to continuing efforts to limit the increase to 1.5 degrees Celsius by 2100.

In the coming years, Canada’s economy and energy systems will undergo a transformation as the country pursues a goal of net-zero[1] emissions by 2050. In this context, during 10 meetings between 4 April 2022 and 22 September 2022, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Natural Resources (the Committee) studied the measures needed to transition Canada’s energy system towards a fair and equitable net-zero future.

The complexity of this transition was reflected in the Committee’s study, which covered a wide range of challenges and opportunities affecting individuals, groups, communities and industries across Canada. This report presents the evidence on these topics under six themes:

- 1) Understand the transition;

- 2) Learn from experience and best practices;

- 3) Establish frameworks for planning, engagement and reconciliation;

- 4) Promote a resilient, net-zero energy sector;

- 5) Strengthen local supply chains for net-zero industries;

- 6) Support communities and equip workers with the skills for a net-zero economy.

Building on these themes and drawing from the insights the Committee heard during its study, this report recommends actions that the Government of Canada can take to ensure that a net-zero transition creates opportunities for all Canadians. The Committee thanks all witnesses for their contributions for this study.

Understand the Transition

Canada will be better prepared to manage a net-zero transition if its governments, industries, workers and communities have a better understanding of what the transition is and where it is taking them. The following sections of this report describe the concepts and principles that are relevant to this transition, as well as steps the Government of Canada can take to better measure its progress toward a net-zero future.

Energy Transition

One of the drivers of the Committee’s study—and a theme in much of the testimony—was the concept of an energy transition. As the Alberta Federation of Labour explained in a written brief:

In the simplest sense, an energy transition is the substitution of one source of energy for another. For example, cheap petroleum and the internal combustion engine displaced steam and animal-power during the first half of the 20th century while new energy sources (natural gas, nuclear) were added during the second half. The current energy transition involves switching from coal, oil, and gas to clean electricity and low-carbon fuels like hydrogen.

This transition is motivated by a desire to reduce the risk posed by climate change. As witnesses explained, the world’s current energy system is emitting unsustainable quantities of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, warming the planet and increasing the risk of dangerous effects across the globe. Most of these emissions are produced by the combustion of fossil fuels, chiefly coal, oil and natural gas. To avoid these emissions and reduce the risk posed by climate change, societies must “decarbonize” by adopting lower-emitting forms of energy.[2]

Canada has committed to reduce its own emissions to net-zero by 2050. This commitment echoes a report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which concluded that to avoid the worst impacts of climate change the world must reduce global emissions to net-zero by 2050. For Canada to reduce its emissions in line with a net-zero future, the country will have to be part of a global solution as it undergoes an economic transformation.[3] The remainder of this report explores how Canada can achieve this transition in a fair and equitable way.

Recommendation 1

That the Government of Canada set clear targets for getting to net‑zero with a clear plan to meet these targets.

The Global Energy Transition

Some witnesses suggested that a global energy transition is already underway. As Gil McGowan, from the Alberta Federation of Labour, stated, “the question is not if it's going to be a transition, but what kind of transition it's going to be. Is it going to be an orderly transition or a disorderly transition, or a planned transition or an unplanned transition?” Hadrian Mertins-Kirkwood, Senior Researcher at the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives (CCPA), similarly suggested that Canada has a choice, between “a just and managed transition to a lower-carbon economy or, alternatively, an unplanned collapse reminiscent of so many previous resource busts.”

Noting that “the world is moving away from fossil fuels whether we like it or not,” Mr. Mertins-Kirkwood highlighted a point that a few witnesses made, that Canada’s energy transition would be affected by the climate commitments of other countries. Merran Smith, the Chief Innovation Officer at Clean Energy Canada, underscored that Canada’s “largest trading partners are investing billions in these newly imagined economies. The EU's race to reduce its dependence on imported fossil fuels foreshadows where the global economy is going.” Nichole Dusyk, senior policy advisor at the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD), noted that as other “countries implement ZEV [zero-emission vehicle] mandates and other climate policies, global demand for oil and gas will drop.”

Indeed, witnesses referenced job losses within the oil and gas sector as a signal that the energy transition is already happening. Gil McGowan pointed out that since 2014, there have been 40,000 job losses in Alberta’s oil and gas sector, leaving 130,000 workers in that sector. While acknowledging that such losses are due, in part, to a drop in the price of oil, he stated that “the industry is not the engine of job creation that it once was, and it never will be.” Professor Éric Pineault, from the Institute of Environmental Sciences of the Université du Québec à Montréal, added that job losses in the oil and gas sector since 2014 are also due to “huge productivity gains.” Furthermore, Kevin Nilsen, President and CEO of the Environmental Careers Organization of Canada (ECO Canada), pointed out that salaries within the oil and gas sector “aren't as high as they were” in 2014.

Providing a different point of view, Dale Swampy, President of the National Coalition of Chiefs, stated his organization’s perspective that

[w]e don't see a transition happening. It's not. Global demand for oil and gas has never been higher. In fact, there's an energy crisis and the G7 is calling for producers around the world to pump out more. Canada has never exported more oil; we are at record levels. Oil and gas companies are making more money than they have in their history, and the federal government is making more revenues off them than ever before.

Mr. Swampy continued in saying, however, that “we believe the transition has to exist in both Canada and the rest of the world.” He contended that Canada was better prepared to transition towards blue hydrogen and biofuels than other forms of low-carbon energy.

Identifying and Measuring the Impacts of a Net-Zero Transition

A transition toward net-zero will be easier to manage if it is fair and can be measured. The use of indicators and metrics can help Canadians understand whether a transition is happening and what effects it is having. The Committee heard that these tools can also help the Government of Canada develop more effective programs and track their progress.[4]

The Government of Canada does not have all the information or tools that it needs to measure a transition. Jamie Kirkpatrick, Program Manager at Blue Green Canada, stated that “[f]rankly, federal departments and agencies have not established frameworks to measure success, to monitor the work or to support Canadians in this transition.” Mr. Kirkpatrick was among a few witnesses who referenced a recent report by the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development (CESD) on the government’s just transition planning, which found that “Natural Resources Canada and Employment and Social Development Canada were not prepared to support a just transition to a low‑carbon economy for workers and communities.”[5]

The Committee heard recommendations addressing the need to better understand which regions and sectors will be the most affected by a net-zero transition. Officials from Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC) indicated that the department has already identified certain sectors that will be “significantly impacted,” either positively or negatively, by a transition. These sectors are:

- clean technology;

- agriculture;

- construction;

- natural resources and environment; and

- transportation.

An official from Natural Resources Canada (NRCan) added that the department considers clean electricity production, hydrogen and biofuels production, critical minerals, and zero-emission vehicles to be job-creating industries of the future.

Witnesses argued that there is a need for more detailed analysis. Patrick Rondeau, Union Advisor for Just Transition at the Fédération des travailleurs et travailleuses du Québec (FTQ), suggested that the Government should extend its analysis to the regional level by conducting prospective studies about the impacts of decarbonization on specific industrial areas. Similarly, Sandeep Pai, Senior Research Lead for the Global Just Transition Network at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, proposed “mapping” the potential for clean energy jobs at the community level.

“Transitioning to a net-zero economy may very well increase overall employment opportunities. However, we know that employment effects will vary by country and by region.”

Tricia Williams, Director, Research, Evaluation and Knowledge Mobilization, Future Skills Centre

The Committee heard some evidence about the types and locations of clean energy jobs. Merran Smith summarized research from her organization, Clean Energy Canada, which found that approximately 209,000 jobs could be created in the “clean energy sector” by 2030. These include jobs in generating and transporting clean energy, reducing energy consumption and making low-carbon technologies like zero-emission vehicles. In contrast, their modelling projected the loss of 125,800 jobs in fossil fuel industries by 2030.

According to Michael Burt, Vice President at the Conference Board of Canada, his organization has estimated that approximately 900,000 jobs—representing about 5% of Canada’s workforce—are considered “green.” According to their research, these jobs include work in three key areas: clean energy, energy efficiency and environmental management. The number of green jobs and their share of the workforce is expected to rise in the coming decades. However, Mr. Burt said that job creation and training may differ across regions of Canada:

[O]pportunities vary quite a bit depending on where you are in the country. For example, on a relative basis, Ontario and Alberta have much more opportunity, while Atlantic Canada has less. The cost of training is also quite different, depending on what region you're in. In Alberta, it's very high. Quebec is the lowest in the country, and the gap is quite large. It's about a 30% difference between the two provinces.

In addition to differences across regions, the effects of a transition will differ across groups and individuals. Historically, marginalized groups, including Indigenous peoples and non‑white workers, face higher barriers to obtaining education, training and jobs, which can make it harder for members of these groups to respond to a transition. These challenges are exacerbated by the discrimination that members of these groups may experience in the workplace.[6] Similarly, Michael Burt testified that “older workers, those without tertiary education and those with deficiencies in fundamental skills are less likely to be given training opportunities, but they are also the ones who are most in need of upskilling.”

Economic transitions can have psychological effects as well. Changing or losing a job can be extremely stressful or life-altering for a worker and their family. Likewise, the closure of an industry or the displacement of a community can cause people to lose their sense of culture or identity.[7] Later sections of this report describe social protection measures, like worker retraining, that can help workers and communities cope with the effects of transition.

Recommendation 2

That the Government of Canada collaborate with provinces and territories, municipalities and communities, businesses, organized labour, Indigenous governments and communities and other partners to:

- conduct industry-by-industry analyses, disaggregated by region, that assess the potential labour market impacts of a net-zero transition;

- identify individuals and groups who are disproportionately vulnerable to negative effects from a net-zero transition; and

- publish the results of these analyses.

A “Just Transition”

Throughout its study, the Committee heard some calls for Canada’s transition to net-zero to be a “just transition.” The concept of a just transition has long been connected to the relationship between the economy and the environment. The North American labour movement first developed the concept, calling for programs to support workers who lost jobs or income because of new environmental protection policies.[8] Since then, the International Labour Organization (ILO) and the parties to the Paris Agreement have used the term to refer to the importance of ensuring that workers have access to decent and sustainable jobs in the context of the world’s response to climate change.[9]

The Government of Canada has used the term “just transition” in recent consultations about its climate policies. According to Debbie Scharf, Associate Assistant Deputy Minister of the Energy Systems Sector at NRCan, just transition is “a policy approach that puts people at the centre of the Government of Canada's climate policy.” The government has drafted “just transition principles” and invited feedback on them during its consultations.

Principles from the Government of Canada’s Discussion Paper on People-Centred Just Transition

- 1) Adequate, informed and ongoing dialogue on a people-centred, just transition should engage all relevant stakeholders to build strong social consensus on the goal and pathways to net‑zero.

- 2) Policies and programs in support of a people-centred, just transition must create decent, fair and high-value work designed in line with regional circumstances and recognizing the differing needs, strengths and potential of communities and workers.

- 3) The just transition must be inclusive by design, addressing barriers and creating opportunities for groups including gender, persons with disabilities, Indigenous Peoples, Black and other racialized individuals, LGBTQ2S+ and other marginalized people.

- 4) International cooperation should be fostered to ensure people-centred approaches to the net-zero future are advancing for all people.

Source: Government of Canada, People-Centred Just Transition: Discussion Paper.

The Committee invited witnesses to comment on possible principles and a definition of just transition:

- Noel Baldwin, Director of Government and Public Affairs at the Future Skills Centre, responded that just transitions are “economic transitions that meet climate targets and provide people who are transitioning, whether for opportunity or as a result of disruption, with the kinds of jobs that allow them to support their family, meet their obligations and have dignified work.”

- Larry Rousseau, Executive Vice-President of the Canadian Labour Congress, and Samantha Smith, Director of the Just Transition Centre at the International Trade Union Confederation, referred the Committee to the ILO’s guidelines for a just transition.[10]

- On this point, Rosin Reid, Director of the Energy and Environmental Policy Division at NRCan, told the Committee that the department had referred to the ILO guidance when developing its discussion paper, and “tried to come up with some principles that would complement what they're telling us are the best practices.”

- Seamus O’Regan, Minister of Labour, said that just transition “means that we have the ability to point workers in the right direction where we need them to lower emissions, to build up renewables and to continue the prosperity of this country.” However, the minister commented that he and the Minister of Natural Resources would prefer not to use the term “just transition,” saying that it is viewed unfavourably by workers in some sectors.

- Sari Sairanen, National Director of Health, Safety and Environment at Unifor, suggested that the government should adopt the principles outlined in the final report of the Task Force on Just Transition For Canadian Coal Power Workers and Communities.

- Hadrian Mertins-Kirkwood said that the government should explicitly call for an end to the use of fossil fuels, explaining that “we need to stop talking about emissions reductions in the abstract and be clear about the end goal.”

- Sharleen Gale, Chair of the Board of Directors of the First Nations Major Projects Coalition, said the Government of Canada should ensure that measures to achieve net-zero emissions “do not disadvantage First Nations communities, further creating hardship to Indigenous communities.”

Recommendation 3

That the Government of Canada set clear goals and principles based on Canada’s international climate obligations and responsibilities to Indigenous peoples, in partnership with workers, communities and other stakeholders, and that these principles reflect:

- Canada’s obligation to address the climate crisis; and

- the need to ensure that Canadian workers and communities, and Indigenous peoples, benefit from investments in a clean technology future.

Witnesses also responded to the notion of a “people-centred” transition. Unifor's representative objected to the term “people-centred,” saying it “waters down the original focus on the needs and challenges faced by workers in fossil fuel-dependent industries undergoing transition.” Lionel Railton, Canadian Regional Director of the International Union of Operating Engineers, likewise said that a just transition should be “worker centric.”

Other witnesses disagreed, saying that policies focused on supporting workers might be too narrow and would exclude other people who will be affected by a net-zero transition. The CCPA representative offered an example from the energy sector:

Providing broad support is important from an equity perspective, because while the people who work in the energy industry today are disproportionately high-income white males who were born in Canada, the people who depend indirectly on that industry—who, for example, make lunch for energy workers and also lose their jobs when a project closes down—are more likely to be low-income women, racialized workers and immigrants. Just transition policies that are too narrow can make inequality worse and further marginalize historically excluded groups.

Along the same lines, Luisa Da Silva, Executive Director at Iron and Earth, argued that the government should work with communities rather than workers alone, to address the “entire ecosystem” of social and economic life in communities that will be affected by transition.

Recommendation 4

That the Government of Canada take a broad approach to assessing the risks and opportunities associated with a net-zero transition, emphasizing the needs of workers while also identifying the indirect opportunities and impacts of the global net-zero transition on other individuals, groups and communities.

Recommendation 5

That the Government of Canada recognize that the transition to net‑zero, while being a huge opportunity for growth in the clean tech sectors, must also work to alleviate negative impacts on regions and communities, and wherever possible, promote local production while supporting workers in dependent industries and affected domestic supply chains.

Learn From Past Experience and Best Practices

To ensure a successful transition, witnesses outlined a few ways that Canada could learn from past experiences and best practices. Nichole Dusyk highlighted that

Canada has been through difficult labour transitions before. Whether that's the boom and bust in the oil patch or whether it's the collapse of the cod fishery, we do have experience and we understand what is at stake and how important it is to proactively plan and ensure that supports are in place for workers and for communities.

Some witnesses referenced Canada’s coal sector transition, as well as transition plans in other countries as examples of past experience and best practices for Canada to undertake a transition to a low-carbon economy.

Canada’s Coal Transition

Government policies can trigger transitions away from certain types of energy, such as coal. Coal-fired electricity generation is the largest single source of carbon dioxide emissions globally.[11] In December 2018, Canada’s federal government committed to phase out traditional coal-fired electricity by 2030. Hadrian Mertins-Kirkwood described this 2030 deadline as “essential […] because it gave affected workers, their communities and the industry certainty about the future.” In November 2021, the federal government also committed to banning the export of thermal coal—which is mainly used for coal-fired electricity—by 2030.

Most Canadian provinces and territories have eliminated coal as a source of electricity. Yet, as witnesses from NRCan and ECO Canada pointed out, Alberta, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Saskatchewan continue to use coal as an electricity source. A planned transition away from coal as a source of electricity will affect employment, families and communities in those regions. Likewise, the Committee received a written brief from a coal exporter in British Columbia, Westshore Terminals, which pointed out that thermal coal exports account for 60–70% of its sales and revenue and help to support 200 unionized jobs in addition to multiple indirect jobs from service suppliers working with their terminal.

To support the federal government’s commitment to an accelerated coal phase out, the Task Force on Just Transition for Canadian Coal Power Workers and Communities was mandated to provide knowledge, opinions and recommendations to the Minister of the Environment and Climate Change for implementing a just transition. The Task Force’s final report from December 2018 made 10 recommendations in that regard.

In 2022, the CESD published Report 1—Just Transition to a Low-Carbon Economy, which included an audit of the federal government’s implementation of the Task Force’s recommendations. It pointed out that among those 10 recommendations, the government has only implemented four, stating “[f]ederal commitments and programs did not reflect all the task force recommendations.”

In its brief to the committee, the Canadian Chamber of Commerce drew attention to the CESD’s report, noting that “the [coal] transition has been handled on a business-as-usual basis, relying on existing program mechanisms such as the employment insurance program to deliver support.” Westshore Terminals highlighted that “the gender-based analysis plus undertaken for the coal transition programs did not reflect the diversity of the workers in the sector.” The Blue Green Canada representative pointed out that fulfilling the recommendations of the Task Force would require interventions from multiple departments and agencies, and “[t]he result was that no one was given the jobs to do, so the jobs then didn't get done.”

The FTQ’s brief called on the federal government to “act now on the recommendations of the Just Transition Task Force of Canada to meet with communities and coal power workers.”

Recommendations of the Task Force on Just Transition for Canadian Coal Power Workers and Communities

- 1) Develop, communicate, implement, monitor, evaluate, and publicly report on a just transition plan for the coal phase-out, championed by a lead minister to oversee and report on progress.

- 2) Include provisions for just transition in federal environmental and labour legislation and regulations, as well as relevant intergovernmental agreements.

- 3) Establish a targeted, long-term research fund for studying the impact of the coal phase-out and the transition to a low-carbon economy.

- 4) Fund the establishment and operation of locally-driven transition centres in affected communities.*

- 5) Create a pension bridging program for workers who will retire earlier than planned due to the coal phase out.

- 6) Create a detailed and publicly available inventory with labour market information pertaining to coal workers, such as skills profiles, demographics, locations, and current and potential employers.

- 7) Create a comprehensive funding program for workers staying in the labour market to address their needs across the stages of securing a new job, including income support, education and skills building, re-employment, and mobility.

- 8) Identify, prioritize, and fund local infrastructure projects in affected communities.*

- 9) Establish a dedicated, comprehensive, inclusive, and flexible just transition funding program for affected communities.*

- 10) Meet directly with affected communities to learn about their local priorities and to connect them with federal programs that could support their goals.*

Note: The symbol * indicates recommendations implemented by the Government of Canada, according to the Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development.

Source: Government of Canada, Final Report by the Task Force on Just Transition for Canadian Coal Power Workers and Communities: section 7.

Recommendation 6

That the Government of Canada implement all 10 recommendations from the Task Force on Just Transition for Canadian Coal Power Workers and Communities, and report on the implementation of those recommendations.

There are several factors that differentiate the coal transition from the net-zero transition. For example, the Alberta Federation of Labour's representative outlined some differences between the coal-fired power industry and the oil and gas sector, stating that “we can’t simply cut and paste what we did in the coal-fired power industry and apply it to oil and gas.” These differences include:

- The smaller scale of the coal industry, at 2,000 workers, compared to 130,000 workers in Alberta’s oil and gas sector alone.

- The lower rate of unionization in the oil and gas sector, making it more difficult to communicate with workers.

- The difficulty of identifying the factors that lead to job losses in the oil and gas sector, which include climate policies, market forces and technology advancements. These factors make it “much harder to decide who should qualify for benefits.”

Just Transition Approaches Around the World

Some witnesses mentioned notable just transition policies in other countries. The FTQ's brief recommended that the Committee study Scotland and Ireland’s commissions on just transition, and Spain’s efforts on a just transition, highlighting that the Scottish government requires that its Just Transition Commission reports to Parliament and publishes a report every year. Hadrian Mertins-Kirkwood noted that New Zealand and Scotland have implemented coordinating bodies to oversee a just transition, given that achieving a just transition requires the involvement of many government departments. He pointed out that Denmark and New Zealand have committed to phasing out oil production, and accordingly, can develop industrial and social policy that creates alternative jobs in the green sector. Similarly, Sandeep Pai referenced South Africa’s inter-ministerial committee on a just transition, which comprises “members from various ministries, including from provinces or states that are impacted.” Speaking on behalf of NRCan, Debbie Scharf mentioned that the federal government had also examined “just transition” measures in the European Union and in Germany.

A brief submitted by the Association of Consulting Engineering Companies–Canada (ACEC–Canada) reported that Canada’s infrastructure spending lags behind that of other nations. ACEC–Canada recommended that Canada increase its infrastructure investments, which could “help to enable an energy transformation, especially for workers whose skills may transfer well from energy-intensive sectors to delivering more clean-energy-enabling infrastructure.”

Providing a different perspective, Shannon Joseph, Vice-President of Government Relations and Indigenous Affairs at the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers (CAPP), said that:

Even before the Russian invasion of Ukraine, oil and natural gas prices had been rising as a result of supply shortages and a decline in energy development. An important driver for this decline has been policy signals from governments and the investment community that are misaligned with global energy demand.

Table 1—Selected Just Transition Initiatives Around the World

Governing Authority |

Type of Measure |

Notes |

European Union |

Funding mechanism |

The European Union has adopted a Just Transition Mechanism to address the social and economic effects of a low-carbon transition. The mechanism funds economic diversification, energy efficiency and infrastructure projects in member states, among other initiatives. |

Germany |

Strategy and planning |

Germany conducted a multi-decade transition process for its main coal-producing region, the Ruhr. Among other things, this process included proactive economic planning, the establishment of new educational institutions and stricter environmental policies. |

Germany |

Engagement |

In 2018, Germany established a commission to advise the government on phasing out coal and planning transition measures for the coal sector. |

New Zealand |

Coordination |

In 2018, New Zealand established a Just Transitions Unit within the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment. It conducts research and advises the government about transitioning to a low-carbon economy. Functionally, its purpose is to play a coordinating role and serve as a centre of expertise within government. |

Scotland |

Strategy and planning |

Scotland is developing a National Just Transition Planning Framework to help the government develop transition plans that are consistent with its climate goals. |

Scotland |

Engagement |

The Scottish Government has established two just transition commissions (2019–2021 and 2022–present) to scrutinize and advise on the government’s sectoral and regional “just transition plans.” These plans are intended to help Scotland reduce its emissions to net-zero while supporting workers and communities. |

South Africa |

Coordination |

The President of South Africa convened an Inter-Ministerial Committee on the Just Energy Transition Partnership to coordinate national planning for a low-carbon transition. |

Sources: Government of Spain, Just Transition Agreements: Update March 2021; New Zealand, Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment, Just Transition; The Presidency of the Republic of South Africa, “President Ramaphosa outlines South Africa’s Just Energy Transition Investment Plan,” 4 November 2022; Scottish Government, Just Transition—A Fairer, Greener Scotland: Scottish Government response, 7 September 2022; and Scottish Government, Just Transition Commission.

Establish Frameworks for Planning, Engagement and Reconciliation

The lessons of the past and the experience of other countries may be useful as Canada develops its own approach to managing a net-zero transition. As the following sections outline, the Committee heard that the federal government could better organize, communicate and coordinate its transition measures.

Outlining a Vision and a Strategy

Change creates uncertainty. While Canada has committed to achieving net-zero emissions, the exact path to its goal and the precise effects of transition are unclear. Many witnesses emphasized the importance of counteracting this uncertainty.[12] To this end, various witnesses recommended that the federal government should outline a clearer vision and strategy for Canada’s net-zero future.[13]

“We're currently dealing with a significant trust deficit. People are fearful. What they really need is a plan.”

Tara Peel, Political Assistant to the President, Canadian Labour Congress

Witnesses who represent organized labour said that the lack of a plan is creating fear among workers and undermining their trust in government. According to the representative of the International Union of Operating Engineers, “there seems to be no blueprint and no real clear objectives, but just a lot of talk. This uncertainty creates distrust and unease among those who will eventually be impacted: the workers.” Gil McGowan concurred, saying that Canada needs “an industrial plan” established and funded by all orders of government. The representative from the Canadian Labour Congress added that a plan should also include “the types and numbers of jobs that will be needed to meet the needs of a net-zero economy.”

Implementing a net-zero plan will require significant public and private spending. The Government of Canada has already taken some steps in this regard; an NRCan official referred to $9 billion in spending from the 2030 Emissions Reduction Plan and “the $100 billion in previous plans.” However, the CCPA's representative pointed to calculations from the 2022 federal budget that estimated the spending needed to attain net‑zero at $100 billion to $125 billion a year, of which only $15 billion to $25 billion is currently being spent. The CCPA said it was not the Government of Canada’s sole responsibility to make up this shortfall, but that the government was still not spending its share.

Nichole Dusyk, speaking for the IISD, agreed that the public and private sectors should both play a role in financing a net-zero transition. She added that the federal government should “ensure that corporate accountability is maintained and upholds the ‘polluter pays’ principle, and at the same time minimizes public financial liability.”

The Alberta Federation of Labour's representative recommended that at least some federal spending take the form of a “just transition transfer” from the Government of Canada to the provinces and territories.

Recommendation 7

That the Government of Canada commit adequate financial resources and establish robust policy and legislative frameworks necessary to lay out a clear path to a sustainable net-zero economy focused on job creation, skill development and making use of Canada’s advantage in clean tech resources, while respecting the jurisdiction of the provinces and territories.

Recommendation 8

That the Government of Canada end fossil fuel subsidies and establish a sustainable investment plan to develop a net-zero economy.

The Minister of Labour affirmed that the federal government will “deliver a comprehensive action plan.” He explained that this was the intended purpose of the government’s forthcoming just transition legislation.

However, some witnesses cautioned that legislation on its own is insufficient.[14] For example, the IISD’s representative said that the Government of Canada must also think about complementary measures, not just legislation. These witnesses explained that legislation should form part of a proactive “just transition strategy” that outlines funding mechanisms, economic diversification strategies, training and reskilling, as well as monitoring and evaluation. The FTQ’s representative agreed that the federal government needed to adopt a just transition strategy, adding that this strategy must not use a “one size fits all” approach. Instead, it called for the government to establish sectoral transition plans.

Recommendation 9

That the Government of Canada establish region- and sector-specific planning and reporting requirements in supporting the growth of sustainable jobs and that progress reports on the implementation of these plans be reported to Parliament on an annual basis.

The Government of Canada noted that the forthcoming just transition legislation and other federal measures will provide some information about how a net-zero transition would affect different economic sectors. An official from NRCan noted that the federal 2030 Emissions Reduction Plan “set a sector-by-sector approach to look at emissions reductions between now and 2030” and “provided guideposts for action.” An official from the department affirmed that the 2030 Emissions Reduction Plan and the just transition legislation would “help us understand the directions we need to take” and “make decisions on how to bring the right skills and the workers to the jobs of the future.”

The representative from Blue Green Canada offered a counterpoint, saying that “the federal government has climate plans, but it does not have plans that lay out the future of workers.” He said that governments can help provide certainty by answering questions such as: “are there going to be constraints on oil and gas production? Are we going to take the steps needed to limit temperature rise to 1.5°[C]? Are we going to be able to do so in a fair way?”

Shannon Joseph, from CAPP, agreed about the importance of certainty but said the best way to provide it was to adopt policies that accelerate permitting and construction while “allow[ing] investors to invest with confidence.”

Developing Inclusive Engagement Processes

Engagement processes can help governments adapt their policies to the realities of different communities and build trust between the many groups that will shape a net‑zero transition.[15]

The ministers of Labour and Natural Resources described two tools that the Government of Canada plans to use to consult Canadians about the energy transition. The first tool is the Regional Energy and Resource Tables. These tables bring the federal government together with provinces, territories, Indigenous communities and other partners with the aim of identifying regional economic development strategies that are aligned with net-zero.[16] The second tool is a just transition advisory body, which has not yet been established. As the Government of Canada explains in its discussion paper on people-centred just transition, it intends for the advisory body “to provide the government with advice on regional and sectoral just transition strategies that support workers and communities.”

The Committee heard that the following groups should be part of such an advisory body:[17]

- affected workers and labour organizations;

- employers;

- communities, particularly affected communities; and

- Indigenous peoples.

For its part, the FTQ criticized the proposal to establish an advisory body. In its brief, the organization wrote that “we find the idea of setting up another advisory council outdated. We are convinced that we are ready for a more effective structure.” The FTQ recommended that Canada instead consider the “just transition” approaches adopted in Scotland, Ireland and Spain.

Engagement processes need not be limited to the federal level. Charlene Johnson, CEO of Energy NL, recommended that each province should have an advisory body “composed of government, industry, labour and other stakeholders.” Representatives from Green Blue Canada and the FTQ said that the government should support the establishment of joint committees within workplaces for workers and employers to discuss transition planning.

“Good outcomes for Canadian workers will emerge from good, inclusive processes.”

Nichole Dusyk, Senior Policy Advisor, International Institute for Sustainable Development

For consultations led by the federal government, the IISD's representative recommended the use of a “tripartite-plus” format. According to the ILO, tripartite social dialogue refers to consultation and cooperation between public authorities and social partners, while tripartite-plus refers to situations where these partners open up the dialogue and engage other civil society groups. Labour organizations have called for the Regional Energy and Resource Tables to follow a tripartite format as well.

Recommendation 10

That the Government of Canada adopt a tripartite-plus approach (all orders of government, including Indigenous governments and affected municipalities; employers; and workers) that employs strong, ongoing social dialogue and an equity focus to establish standards, policies and programs related to labour.

Pursuing Fairness and Reconciliation

The Government of Canada must not only engage with Canadians: it must ensure that they can prosper in a net-zero future. Witnesses emphasized that the economic opportunities of this future should be made available to all Canadians, particularly those who have historically been marginalized.[18] In the words of Denis Bolduc, General Secretary of the FTQ, “[j]ust transition is about fairness.”

As this report has described, economic transitions can deepen existing inequalities. Accordingly, some witnesses said that government policies should focus on providing opportunities to the groups that are most vulnerable to a transition. “The lesson is not that energy workers don’t deserve support in this transition,” Hadrian Mertins-Kirkwood explained:

Of course, they absolutely do. The lesson is that we need to think bigger and more comprehensively about how entire communities transition to ensure that the costs of this inevitable shift to a clean economy are shared fairly and that the benefits are shared equitably with everyone.

In this vein, the Canadian Chamber of Commerce’s brief recommended that historically marginalized Canadians should be prioritized for public procurement projects, and suggested that the private sector should partner with these groups to receive decarbonization funding.

For these reasons, a net-zero transition could be an opportunity for Canada to advance reconciliation with Indigenous peoples, who are among the groups that have historically been marginalized and denied opportunities available to other Canadians. The First Nations Major Projects Coalition's representative called for measures that would enable Indigenous peoples to obtain equity in clean energy projects, saying that Indigenous involvement “brings value not only to First Nations but also to Canada's economy, in the form of investor certainty.” Ian London, Executive Director of the Canadian Critical Minerals and Materials Alliance, agreed with this recommendation and added that Indigenous peoples should also be able to invest in value-added parts of the supply chain.

Recommendation 11

That Natural Resources Canada develop measures to enable greater Indigenous participation in—and ownership of—clean energy and natural resources projects.

Recommendation 12

That the Government of Canada establish clear rules to ensure companies that receive public money for net‑zero investments have obligations to ensure domestic jobs with good employment standards and obligations for Indigenous involvement while considering the need to maximize economic benefits for communities.

Speaking more generally, the IISD's representative said that any transition funding should be designed to uphold Indigenous rights. Other witnesses agreed, though the Committee heard different views about how government policies could affect Indigenous rights. Kukpi7 (Chief) Judy Wilson, representing the Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs, insisted that just transition legislation must recognize the Indigenous rights contained in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). Chief Wilson warned that a net-zero transition should not become “a similar extractive economy, in which Indigenous peoples’ rights are ignored and ecosystems are destroyed for clean energy” rather than fossil fuels.

Witnesses also cautioned that certain government policies could interfere with the ability of Indigenous peoples to participate in certain economic development projects. The representative from the National Coalition of Chiefs expressed concern that the federal government’s legislation to implement UNDRIP could become “a vehicle for the government to be able to stop projects that First Nations are supporting.” The First Nations Major Projects Coalition's representative and Chief Delbert Wapass, a Board Member of the Indian Resource Council, agreed that the federal government should not advance policies that prevent Indigenous peoples from deciding which projects to pursue.

Improving Coordination

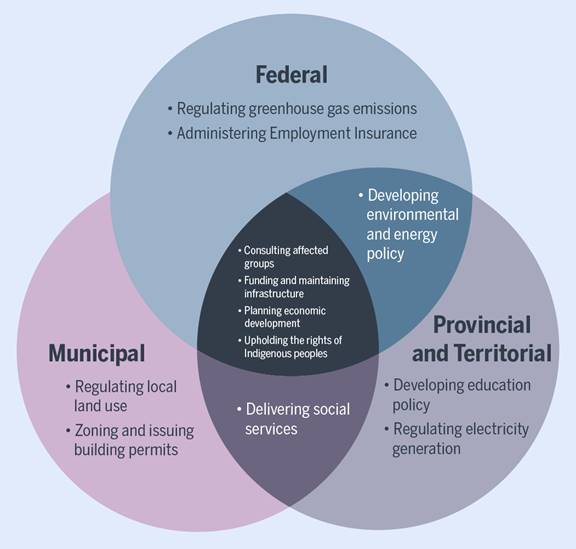

A successful net-zero transition will require collaboration within and between all orders of government. The Committee heard repeatedly that Canadian governments must coordinate their efforts more effectively. “What we’ve done so far,” according to Jamie Kirkpatrick, “is divide this work across many government ministries.” To illustrate this challenge, Figure 1 shows some responsibilities of different orders of government that may be relevant to a net‑zero transition.

Figure 1—Selected Government Responsibilities Relevant to Net-Zero Transition

Source: Figure prepared by the Committee.

There are many possible remedies. A representative for the FTQ proposed that Canada should appoint a deputy minister for just transition and establish a body “similar to a Crown corporation” that would implement a transition. Luisa Da Silva said that the federal government should have a “central ministry, group or committee that oversees the development, management and implementation of just transition policy.” She added that an advisory body was insufficient “because advice can be ignored.”

Canada could follow the example of the United States and South Africa by establishing an inter-ministerial committee for the transition.[19] Sandeep Pai proposed that a Canadian committee could include ministries responsible for finance, environment and skills development, among others. Dr. Pai added that such a committee would ideally include representatives from “the most impacted communities.” ATCO’s brief endorsed the idea of an inter-ministerial committee that includes the federal government “and members from key energy producing provinces.”

Recommendation 13

That the Government of Canada legislate a dedicated government body to plan sustainable jobs initiatives and engagement for the ongoing development of a net-zero economy.

Governments should not only coordinate their actions: they should also coordinate their messaging. The Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada commented that strong communication is essential in the context of change. They suggested that individuals and communities are more receptive to messages that outline a positive and realistic vision, and that are delivered by people they trust. The organization commented that certain terms, including “just transition,” may be divisive or unhelpful. They concluded that the federal government can best contribute to a net-zero transition by convening leaders and aligning them “in support of a common narrative that presents both the necessity for change and an optimistic and realistic vision of a positive future.”[20]

Conversely, mixed messaging can undermine an effective transition. For example, Luisa Da Silva argued that the federal government issued confusing messages in 2022 by approving the Bay du Nord offshore oil project “shortly after a very green forward budget was announced and while intergovernmental agencies such as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change are calling for an end to all new fossil fuel projects.” She said these acts sent contradictory signals that make it harder for communities to know what to expect.

Promote a Resilient, Net-Zero Energy Sector

The pathway to a net-zero future runs through Canada’s energy system. At present, the country uses fossil fuels for 74% of its energy needs.[21] While some parts of the energy system are already largely decarbonized, like electricity, the Committee heard that other areas will face more challenging transitions to net-zero. The following sections describe some of the options facing Canada as it looks to build a resilient, net-zero energy sector.

Electrifying Canada’s Energy System

A net-zero world will need significantly more electricity than we use today. Electricity generated from non-emitting sources can play many roles that are currently filled by fossil fuels, including powering vehicles, generating heat for industrial processes and supplying some of the energy needed for resource development, among other uses.[22]

“We know that to get to net-zero, we need to replace fossil fuel power generation with zero-carbon power, at least one to one. It's a simple concept with staggering implications.”

Christopher Keefer, President, Canadians for Nuclear Energy

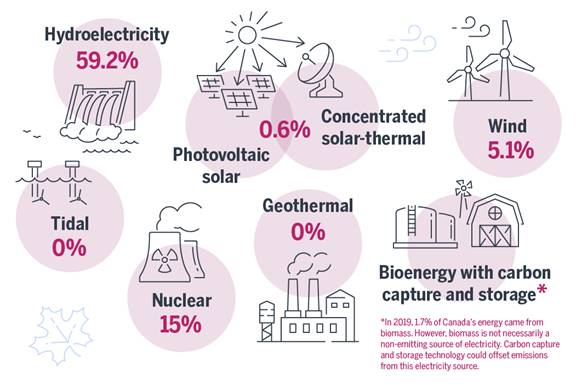

Canada already generates approximately 80% of its electricity from non-emitting sources, chiefly hydroelectricity, followed by nuclear energy and other renewables like wind and solar.[23] However, the country will need to expand its generating capacity to meet its emissions targets. According to various estimates, Canada must double or triple its capacity to generate electricity from non-emitting sources to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050.[24]

The electricity sector itself may have to decarbonize more quickly than the rest of the economy. While Canada aims to achieve net-zero emissions overall by 2050, the Government of Canada has committed to having a net-zero electricity grid by 2035. Francis Bradley, President and CEO of Electricity Canada, described the federal targets as “very aggressive” but affirmed that “the electricity sector is committed to working towards those targets.” To achieve a net-zero electricity system, Mr. Bradley said that Canada must pursue “every non-emitting source of generation.” Figure 2 illustrates some key sources of non-emitting electricity.

Figure 2—Selected Sources of Non-emitting Electricity

Source: Figure prepared by the Committee. Data are from NRCan, Energy Fact Book: 2021–2022.

Citing a study that was conducted before Canada announced its net-zero targets, Electricity Canada's representative anticipated that a decarbonized economy would require investments of $1.7 trillion in the electricity sector, chiefly in new generation and transmission capacity. However, the electricity system needs more than investment. As Mr. Bradley explained, Canada struggles to expand its electricity system because the systems are mostly under provincial jurisdiction and there is no “effective subnational coordination function for the planning and construction of transmission on a regional basis.” He also said:

The reality is that it is more challenging today than it was 10 years ago to build infrastructure. The challenges of siting, the challenges of seeking approvals, the complexity of this work has simply increased. That's just the reality that we need to deal with, and it's something that everybody in the sector is addressing.

Recommendation 14

That the Government of Canada make project approvals more efficient and strengthen Canada’s business case as a first-choice destination for investment in low-carbon resource and energy projects.

Michelle Branigan, CEO of Electricity Human Resources Canada, added that the electricity sector must deal with at least two other challenges as it prepares its workforce for an energy transition. First, she said the sector must fill the gaps being created by “a rapidly retiring demographic,” adding that even more workers appear to be retiring because of the effects of COVID-19. Second, Ms. Branigan noted that the sector’s current workforce “does not represent what the population of the country actually looks like.” In her view, “[w]e have an ethical obligation to ensure that anybody in our society feels capable of pursuing a career, regardless of their gender, their background or any other parts of their identity.”

Ensuring Domestic and Global Energy Security

The illegal Russian invasion of Ukraine has disrupted energy markets around the world, threatening energy supplies and contributing to rising prices, particularly of oil and gas.[25] Jonathan Wilkinson, the Minister of Natural Resources, remarked that as a result, “issues relating to energy affordability and energy security are now very much at the forefront of international affairs.” Prices for many energy products have risen significantly, especially in rural and remote areas—where prices are already higher than in other parts of Canada.[26]

“I've heard some people say today that Canada has had cheap, affordable energy. Perhaps it has, if you've been living in metropolitan areas, but I speak with people who live on reserves and they pay $500 to $700 a month for electricity […] Energy cannot be considered cheap and affordable when a quarter of your pay is going toward electricity.”

Luisa Da Silva, Executive Director, Iron and Earth

Some argued that Canada can best serve its citizens and its allies by acting as a stable supplier of energy, including fossil fuels. In a brief submitted to the Government of Canada and shared with the Committee, the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada affirmed that:

Concerns about energy security will not disappear with the transition to net-zero, and these consultations should be mindful of the role Canada can or should play in meeting the energy needs of its allies, trading partners and, of course, its own population. The oil and gas resources with which Canada has been blessed will continue to be in demand for years to come. As a global good citizen, Canada can play an important part in securing energy stability in the world.[27]

CAPP's representative agreed, telling the Committee that they see “an important role for our industry in meeting increasing global demand for reliable, affordable and responsibly produced energy.”

As discussed in the following section of this report, nuclear energy could also play a role in promoting energy security. Christopher Keefer, President of Canadians for Nuclear Energy, said that nuclear power can provide Canada with reliable energy sourced from mainly domestic supply chains. He suggested that Canada should learn a lesson from the experience of the European Union:

If you look at what's going on with the Russian aggression in Ukraine right now, the EU is completely handicapped in terms of stopping this. They are funding that aggression to the tune of $700 million euros every single day, because they created a wind and solar dominant energy transition backed by natural gas. That's the problem as you were saying of this unreliability and intermittency [of wind and solar power]…Canada could find itself in the same situation with the supply chains I was talking about.

On the subject of energy costs, Merran Smith stated that “[i]n the plainest sense, transitioning to clean energy lowers energy bills.” She said it was true that an energy transition would bring higher electricity use—and therefore higher electricity bills—but that consumers would spend less on energy overall. She explained: “[W]hen you waste less energy and use less wasteful energy, you save money.” Pointing to analysis from the International Energy Agency (IEA), she said that existing policies will lead to lower household energy bills in advanced economies between now and 2050, and that more ambitious policies would drive further decreases.

Other witnesses agreed that energy efficiency measures can help Canadians reduce the cost of energy. According to Daniel Breton, President and CEO of Electric Mobility Canada, the country “ranks first among G20 countries for per capita energy consumption, per capita greenhouse gas emissions, and greenhouse gas emissions from our light-duty vehicles. That means we waste a lot of energy.” While Canada needs new sources of clean energy, he said, the country should also waste less. The Coalition for Responsible Energy Development in New Brunswick submitted a brief noting that “[e]nergy efficiency measures […] will allow citizens at all income levels to reduce their energy demand and hence their energy bills.”

The Role of Nuclear Energy

Some witnesses told the Committee that nuclear energy could help Canada transition to a lower-emitting energy system. One of the advantages of nuclear power is that it can generate large amounts of non-emitting electricity at a relatively constant rate.[28] Christopher Keefer told the Committee that whereas solar panels in Canada typically produce electricity equal to 15% of their maximum capacity and wind turbines produce 30–35%, CANDU reactors produce more than 90% of their maximum capacity.

Witnesses added that the nuclear energy industry offers a range of economic benefits, saying that it generates more jobs, offers higher wages, and relies more heavily on Canadian supply chains than some other industries. Chad Richards, Director of New Nuclear and Net-zero Partnerships at the Nuclear Innovation Institute, cited a 2021 paper from the International Monetary Fund which found that nuclear power creates about 25% more employment per unit of electricity than wind power, while workers in the nuclear sector earn approximately 30% more than workers in renewable industries. Witnesses noted that this workforce is unionized at higher rates than those in the wind and solar industries.[29]

According to Christopher Keefer, the nuclear industry’s supply chain “is 96% made in Canada. That includes the mines, fuel fabrication, heavy industry, construction, operation, maintenance and spent fuel handling.” Furthermore, nuclear technology can be exported. As Dr. Keefer noted, Canada’s CANDU reactor technology is used around the world.

An expansion of nuclear power in Canada would require significant investment. Dr. Keefer suggested that the cost might be on the order of “hundreds of billions of dollars,” though he contended that this spending would generate even more value in economic benefits. Chad Richards also noted that the cost of supplying nuclear electricity in Ontario in 2021 was cheaper than wind and solar. To help fund nuclear projects, witnesses and organizations that submitted briefs said the Government of Canada should ensure that nuclear energy is classified as clean energy and eligible for financing through green bonds.[30]

Recommendation 15

That the Government of Canada ensure that nuclear energy projects are classified as clean energy projects and made eligible for sustainable finance.

Two groups submitted briefs opposing such spending. The Rural Action and Voices for the Environment (RAVEN) project at the University of New Brunswick and the Coalition for Responsible Energy Development in New Brunswick argued that nuclear energy projects would lead to higher energy costs compared to other non-emitting sources. They noted that the cost of renewables is falling, whereas nuclear reactor construction and refurbishments have typically run over budget. Their briefs also opposed federal support for emerging reactor designs known as small modular reactors (SMRs) saying that there is insufficient demand for SMRs to be built at the scale needed to generate returns.

Nuclear energy also generates hazardous waste that must be stored and managed. In its brief, the RAVEN project described the existence of this waste as another reason not to spend public money on nuclear power. However, Christopher Keefer told the Committee that the risk of nuclear waste has been exaggerated. He said that the country has experience managing its waste safely, though he suggested that Canada ought to build a permanent repository for its nuclear waste.

Oil and Gas in Canada’s Transition

The oil and gas sector employs hundreds of thousands of people (Figure 3), contributes $20 billion in tax revenues and supplies fuels for a range of uses at home and abroad.[31] At the same time, the oil and gas sector is the country’s largest source of GHG emissions.[32] Given that Canada aims to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050, the sector is expected to undergo some transformation. Witnesses offered a range of perspectives on how Canada should approach that transformation.

Figure 3—Direct and indirect employment related to the oil and gas sector in Canada, 2021

Source: Figure prepared by the Committee using data supplied by Natural Resources Canada.

As described earlier in this report, some witnesses argued that the effects of the energy transition are already visible in the oil and gas sector. Indeed, a representative of the FTQ anticipated that oil and gas will be “the most impacted sector in the near future.” Representatives from the Alberta Federation of Labour and Unifor pointed to job losses in the sector in recent years and anticipated that this trend would continue. Gil McGowan, President of the Alberta Federation of Labour, said that the lesson for Canada was to stop “talking about maintaining the status quo” and to start “planning for a future that’s going to look very different from our past.”

In a written brief, the Canadian Association of Energy Contractors (CAOEC) questioned the necessity of a federally planned transition for the oil and gas sector:

By producing cleaner oil and gas, developing alternate energy sources such as hydrogen and geothermal, and perfecting CCUS techniques, Canada’s valuable oil and gas resources, and Canada’s energy services sector can help Canada achieve net-zero. CAOEC thus believes that there is no need for a federal “people-centred just transition initiative.”

CAPP's representative, Shannon Joseph, agreed that Canada’s oil and gas sector should continue to play an important role, not only in ensuring energy security but also by “proactively [advancing] solutions to support Canada’s role in addressing climate change.”

The oil and gas sector has made some progress reducing the emissions created by each unit of oil and gas production. For instance, CAPP declared in its brief that emissions intensity of oil sands mining decreased by 8% to 14% between 2013 and 2019 while that of natural gas, condensate and natural gas liquids decreased by 33% between 2011 to 2019. Ms. Joseph told the Committee that the sector believes it can “decouple” oil and gas production from emissions, theoretically allowing production to increase and emissions to fall. However, these reductions are costly. She testified that if the sector was to meet emissions targets “right now, support would be needed because we are going beyond what is profitable and are coming up against international competition.”

For this reason, Energy NL's representative recommended that the Government of Canada financially support the research, development, demonstration, implementation and adaptation of technology that will help the oil and gas sector achieve net-zero. Canada’s Buildings Trades Union agreed in its brief, adding that the Government of Canada should also invest in large-scale non-emitting energy projects.

Another witness, Éric Pineault, a professor at the Université du Québec à Montréal, expressed skepticism that Canada’s oil and gas sector could deliver absolute emissions reductions that contribute to achieving net-zero. He argued that the country was more likely to “spend money on until 2030 to reduce GHG emissions [per] barrel of oil, while not reducing emissions overall.” Dr. Pineault recommended that policy-makers should focus their efforts on diversifying the economies of oil and gas-dependent regions.

It is true that the oil and gas sector is an important actor in many regions and communities across Canada. For example, witnesses mentioned that there are more than 15,000 businesses in the oil and gas supply chain in Alberta alone, while the sector employs approximately 22,000 people directly and indirectly in Newfoundland and Labrador.[33]

Various witnesses also testified to the relationship between the oil and gas sector and Indigenous communities.[34] Representatives from the National Coalition of Chiefs and the Indian Resource Council both spoke to the economic benefits of oil and gas for economic development in Indigenous communities. As Chief Delbert Wapass, from the Indian Resource Council, explained:

For our members, for many other First Nations, oil and gas provide the best opportunity. It doesn't mean that we aren't interested in other sectors or that we don't want to be part of the net-zero economy, but […] it should be obvious that having a strong oil and gas sector that has meaningful Indigenous involvement and ownership and that is a global leader in environmental, social and governance principles is in the interests of all Canadians.

However, the oil and gas sector can have other effects on communities that should be considered in the context of climate change and energy transition. The representative of the First Nations Major Projects Coalition agreed that Canada has high environmental standards for its projects, but noted that oil and gas projects have also altered local landscapes. Chief Sharleen Gale said that Indigenous knowledge can play an important role in understanding these impacts and recommended that the Government of Canada find more opportunities to integrate Indigenous peoples and traditional knowledge in its work. Herb Lehr said that his organization—the Métis Settlements General Council—wants to “get in at the ground floor” of an energy transition.

Oil and Gas in a Global Transition

As this report has described, energy security is expected to be an enduring consideration for policy-makers around the world. Some witnesses such as Shannon Joseph and Dale Swampy argued that Canada should focus on positioning its oil and gas sector as a pillar of global energy security and stability. At the same time, witnesses expected Canada’s oil and gas sector to come under increasing pressure in a decarbonizing world, including Nichole Dusyk and Hadrian Mertins-Kirkwood, who felt that the country should emphasize a transition away from fossil fuels.

The path that Canada takes will depend partly on the future demand for oil and gas products. The Committee heard some diverging narratives on this point. Whereas CAPP's representative pointed out that the global demand for oil is currently growing, the Minister of Natural Resources emphasized that the IEA expects oil consumption to begin declining by 2030 or 2035, followed by a decline in natural gas consumption. Nonetheless, the world will continue to use petroleum products “for decades to come—if not for fuel, then certainly in various petrochemical products” according to Kevin Nilsen of ECO Canada.

Canada could choose to invest further in its role as a major exporter of petroleum products. CAPP's representative advocated this course, saying that Canadian natural gas could reduce emissions in other countries if it is used to replace coal-fired electricity. Dale Swampy, of the National Coalition of Chiefs, added that Canada should have a competitive advantage because it earns high scores according to environmental, social and governance (ESG) metrics, which are used to assess non-financial dimensions of investments. “I have heard that the last barrel should be a Canadian barrel because of our high ESG standards,” he said, adding: “I think the last barrel should be a First Nations barrel.”

In contrast, some witnesses argued that Canada would be mistaken to assume that there will be continued global demand for its oil and gas. Éric Pineault suggested that Canada’s comparative advantage would be limited in a decarbonizing world because Canadian crude oil is relatively carbon intensive. Sandeep Pai added that future demand for fossil fuels in developing countries may be weaker than generally assumed. Referring to China and India, he said:

Those countries are already deploying large-scale solar and large-scale wind technologies. They're talking about reducing the use of fossil fuels in the long run. Even from a demand point of view, you see that countries that could have been demand centres in the future for these technologies may or may not bite on some of these resources that Canada is trying to export.

Low-Carbon and Renewable Fuels

Decarbonization may increase the demand for low-carbon or renewable fuels that currently play a small role in Canada’s energy system. For example, hydrogen is a potential contributor to Canada’s net-zero fuel mix. Mark Kirby, President and CEO of the Canadian Hydrogen and Fuel Cell Association, argued that hydrogen could play many roles in a net-zero future, from powering vehicles to generating heat and electricity. However, Mr. Kirby warned that if Canada cannot build the infrastructure to support hydrogen use, then “we could miss out on the economic opportunity of the industry as well as miss our commitments to net zero.”

If low-carbon fuels are to be produced on a larger scale, then Canada will need more workers who are trained to handle them. If hydrogen is to be more widely adopted, the Nuclear Innovation Institute's representative mentioned that pipeline construction workers and system safety inspectors would need new certifications, while workers would be needed for new roles like fuel cell retrofit installers and fuelling station managers.

Fortunately, there is some overlap in skillsets between workers in existing and emerging fuel industries. For example, the skillset for workers in biofuels plants are comparable to the skills needed in today’s oil refineries.[35] Clean Energy Canada's representative cited a study which found that more than 90% of the workers in the oil and gas sector in the United Kingdom are well positioned to transfer their skills to other energy sectors. Nevertheless, CAPP maintained in its brief that transition will occur within sectors—such as the oil and natural gas sector—and that demand for skilled workers will continue as their roles evolve to include hydrogen production and carbon capture, utilization and storage functions.

To encourage the domestic production of low-carbon fuels, the Canadian Fuels Association recommended the introduction of a federal low-carbon fuel producer tax credit modelled after Quebec’s tax credit for the production of biodiesel fuel in Quebec. The Canadian Hydrogen and Fuel Cell Association's representative encouraged the federal government to implement the Hydrogen Strategy for Canada and allocate funds from existing clean energy programs specifically for hydrogen spending. It recommended setting aside $800 million for this purpose, with $100 million directed toward the creation of “hydrogen hubs,” which are proposed industrial clusters to be built around a common source of hydrogen.

Recommendation 16

That the Department of Finance Canada assess the scope and effectiveness of current tax measures, such as tax credits, for companies producing low-carbon and renewable fuels in Canada and include assessment of effectiveness of wage obligations and apprenticeship commitments and make changes to these measures as needed.

Recommendation 17

That the Government of Canada work with the hydrogen industry, research and training organizations, Indigenous governments and communities, and provincial, territorial and municipal governments to develop a low-carbon hydrogen industry and national expertise in this field by:

- implementing the Hydrogen Strategy for Canada;

- allocating specific funding envelopes for low-carbon hydrogen production and related infrastructure; and

- helping to build hydrogen hubs in close proximity to production sites and markets where demand for hydrogen could increase.

Strengthen Local Supply Chains for Net-Zero Industries

The effects of a net-zero transition are not confined to the energy sector. As this report has described, this transition is expected to create opportunities across Canada’s economy even as it disrupts high-emitting industries. To seize these opportunities, the Committee heard that the Government of Canada should strengthen local supply chains associated with low-carbon technologies and products. While the country possesses some of the resources, workers and infrastructure for these supply chains, witnesses testified that Canada could do more.[36] The remainder of this section outlines the most promising opportunities that witnesses described and the recommendations they offered for Canada to maximize the benefits of a net‑zero transition.

Mining and Critical Minerals

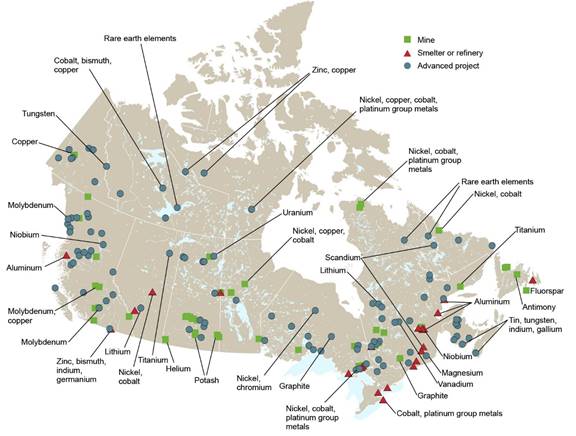

The transition towards a low-carbon economy will lead to a significant increase in demand for minerals that are needed to manufacture low-carbon goods such as electric vehicles, batteries, solar panels and wind turbines. These are sometimes described as “critical minerals.”[37] Canada already produces some of these minerals and has deposits of many others (Figure 4).[38]

Figure 4—Map of Critical Mineral Deposits and Projects in Canada

Note: NRCan defines an “advanced project” as one with mineral reserves or resources (measured or indicated), the potential viability of which is supported by a preliminary economic assessment or a prefeasibility/feasibility study.

Source: NRCan, The Canadian critical minerals strategy, from exploration to recycling: powering the green and digital economy for Canada and the world, December 2022, p. 10.

This Committee recently re-tabled a report, From Mineral Exploration to Advanced Manufacturing: Developing Value Chains for Critical Minerals in Canada, that explores in detail how Canada can support the development of the critical minerals industry and its associated value chains. During the present study, the Committee heard evidence that echoed some of the recommendations in that report.

“Critical materials development and their downstream processing feed major value-creating clean technologies and next-generation jobs.”

Ian London, Executive Director, Canadian Critical Minerals and Materials Alliance

As with other products, Canada can gain a competitive advantage by producing minerals in an inclusive and environmentally responsible way. The Canadian Critical Minerals and Materials Alliance’s brief declared that “[f]airness and solidarity must be defining principles in our critical minerals strategies & plans.” To that end, it recommended that the Government of Canada should consider the end-of-life of any project, including how communities can use its infrastructure. The organization’s president, Ian London, pointed out that manufacturers place value on the traceability of their minerals, and on a low carbon footprint. “It’s fundamental that we […] advance these energy-efficient, greener mining operations” in Canada, he said.

It is not always necessary to establish new mines. Mr. London told the Committee that Canada can use waste products to create value-added products, including materials from tailings ponds and effluent streams.

Witnesses emphasized that the critical minerals industry offers a particularly valuable opportunity because it could serve as the foundation for other value-added industries, like the supply chains for zero-emission vehicles.[39]

Zero-Emission Vehicles and Manufacturing Industries

One of the clearest opportunities for Canada to leverage its access to critical minerals, clean power and skilled workers is in the supply chain for zero-emission vehicles. This supply chain runs from the raw materials needed for vehicle batteries through to vehicle assembly.

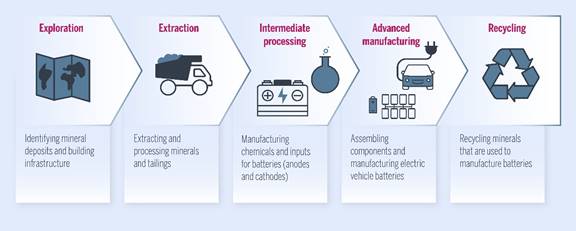

Figure 5—The Battery Manufacturing Value Chain

Source: Figure prepared by the Committee. From Mineral Exploration to Advanced Manufacturing: Developing Value Chains for Critical Minerals in Canada, First report, June 2021.

Various witnesses described the manufacturing of electric vehicle batteries as a major opportunity to generate economic benefits while transitioning to a low-carbon economy. In a previous report, this Committee noted that some links in the battery manufacturing chain did not yet exist in Canada. Since then, Canada has secured some additional investments that will help to develop a battery manufacturing value chain, including a $5 billion investment in a battery factory in Windsor, Ontario.

However, witnesses testified that more work remains to establish this supply chain.[40] Electric Mobility Canada’s representative voiced that, in addition to attracting more investment to Canada’s electric vehicle manufacturing industries in order to spur the development of a domestic zero-emission vehicle supply chain, the federal government should “accelerat[e] technologies, research, development and manufacturing associated with reducing the cost of vehicle batteries,” work with provinces to prioritize training and increase apprenticeship opportunities for electric vehicle mechanics, and build a skilled labour force by supporting employers in training new entrants and “maintaining existing funding commitments for training and retraining.” In the same vein, Clean Energy Canada's representative mentioned that “Canada could do more refining in order to feed into the cathode, anode and cell development and the building out of the whole battery supply, linking in with the auto sector.”