FINA Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

Invocation of the Emergencies Act and Related Measures

Chapter 1: Introduction

On 17 February 2022, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Finance passed a motion to, among other things:

[…] undertake an emergency study on the invocation of the Emergencies Act and related measures taken regarding the 2022 Freedom Convoy, and that:

a) The study examine:

i. the financing of the protest and the blockades;

ii. The broadened scope of Canada’s anti-terrorist financing laws;

iii. The federal government’s increased ability to interfere with the business of crowdfunding websites; including but not limited to new Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Centre of Canada (FINTRAC) regulations with which crowdfunding websites must comply;

iv. The ability of Canadian financial institutions to temporarily and selectively cease providing financial services to specific clients;

v. The increased powers given to Canadian financial institutions to share personal information on anyone suspected of involvement with the 2022 Freedom Convoy;

vi. The long-term impacts of these measures on individual Canadians’ financial futures;

vii. Any other issue or topic related to the extension of powers or their effect on the Canadian financial system by the invocation of the Emergency Measures Act on February 14, 2022.

From 22 February to 17 March 2022, the Committee heard from 15 witnesses over video-conference. These meetings were held in a “hybrid” format, with members attending either virtually or in-person, under strict health and safety protocols.

This report summarizes the testimony brought forward by witnesses, organized into the following chapters: the Emergencies Act and Measures Adopted, Consumer Protection and Account Freezes, Businesses and People Impacted by Blockades, Crowdfunding, Financial Intelligence and Regulation, Government and Departmental Communication, Law Enforcement, and Rights and Freedoms. In addition, the Committee has considered the testimony of GiveSendGo before the Standing Committee on Public Safety and National Security as it relates to the crowdfunding linked to the protests.

In consideration of this testimony, the conclusion of this report lists the Committee’s recommendations to the government.

Chapter 2: The Emergencies Act and Measures adopted

Background

An Act to authorize the taking of special temporary measures to ensure safety and security during national emergencies and to amend other Acts in consequence thereof was enacted in 1988 and may be referred to as the Emergencies Act, pursuant to the short title in section 1.

On 14 February 2022, the Governor in Council proclaimed a public order emergency under Part II of the Emergencies Act, pursuant to section 17 (the Proclamation).

The Proclamation describes the public order emergency as:

(a) the continuing blockades by both persons and motor vehicles that is occurring at various locations throughout Canada and the continuing threats to oppose measures to remove the blockades, including by force, which blockades are being carried on in conjunction with activities that are directed toward or in support of the threat or use of acts of serious violence against persons or property, including critical infrastructure, for the purpose of achieving a political or ideological objective within Canada,

(b) the adverse effects on the Canadian economy — recovering from the impact of the pandemic known as the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) — and threats to its economic security resulting from the impacts of blockades of critical infrastructure, including trade corridors and international border crossings,

(c) the adverse effects resulting from the impacts of the blockades on Canada’s relationship with its trading partners, including the United States, that are detrimental to the interests of Canada,

(d) the breakdown in the distribution chain and availability of essential goods, services and resources caused by the existing blockades and the risk that this breakdown will continue as blockades continue and increase in number, and

(e) the potential for an increase in the level of unrest and violence that would further threaten the safety and security of Canadians.

The temporary measures anticipated by the Governor in Council, as detailed in the Proclamation, are:

(a) measures to regulate or prohibit any public assembly — other than lawful advocacy, protest or dissent — that may reasonably be expected to lead to a breach of the peace, or the travel to, from or within any specified area, to regulate or prohibit the use of specified property, including goods to be used with respect to a blockade, and to designate and secure protected places, including critical infrastructure,

(b) measures to authorize or direct any person to render essential services of a type that the person is competent to provide, including services related to removal, towing and storage of any vehicle, equipment, structure or other object that is part of a blockade anywhere in Canada, to relieve the impacts of the blockades on Canada’s public and economic safety, including measures to identify those essential services and the persons competent to render them and the provision of reasonable compensation in respect of services so rendered,

(c) measures to authorize or direct any person to render essential services to relieve the impacts of the blockade, including to regulate or prohibit the use of property to fund or support the blockade, to require any crowdfunding platform and payment processor to report certain transactions to the Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Centre of Canada and to require any financial service provider to determine whether they have in their possession or control property that belongs to a person who participates in the blockade,

(d) measures to authorize the Royal Canadian Mounted Police to enforce municipal and provincial laws by means of incorporation by reference,

(e) the imposition of fines or imprisonment for contravention of any order or regulation made under section 19 of the Emergencies Act; and

(f) other temporary measures authorized under section 19 of the Emergencies Act that are not yet known.

On 15 February 2022, the Governor in Council made Emergency Measures Regulations, on the basis that “the Governor in Council believes on reasonable grounds, that the regulation or prohibition of public assemblies in the areas referred to in these Regulations are necessary.”

On 15 February 2022, the Governor in council also made Emergency Economic Measures Order, (the Order) on the basis that “the Governor in Council has reasonable grounds to believe that the measures with respect to property referred to in this Order are necessary.”

Following the coming into force of the Order, banks, credit unions, insurance companies, trust and loan companies, crowdfunding platforms and other financial services providers (financial entities) were required to, among other things:

- Temporarily cease providing any financial or related services when an account is being used by, on behalf or for the benefit of any person engaged, directly or indirectly, in prohibited activities set out under sections 2 to 5 of the Emergency Measures Regulations;

- Determine on a continuing basis whether they are in possession or control of property that is owned, held or controlled by or on behalf of these persons; and

- Disclose without delay the existence of any such property, or information about a transaction in respect of that property to the Royal Canadian Mounted Police or the Canadian Security Intelligence Service.

The Order also allowed a federal, provincial or territorial institution to share information to any financial entity subject to the Order if it was satisfied that it would contribute to the application of the Order. In addition, the Order provided that no civil proceedings could be commenced against a financial entity for complying with the Order in good faith.

The motion for confirmation of a declaration of emergency was tabled in the House of Commons on 16 February and debated from 17 to 21 February 2022. The motion passed the House of Commons on 21 February 2022 with a vote of 185 for and 151 against. The Proclamation Revoking the Declaration of a Public Order Emergency was made on 23 February 2022.

Witness Testimony

Speaking broadly on the invocation of the Emergencies Act (the Act), witnesses provided clarification on its use and accountability, as well as made suggestions for its improvement.

Appearing before the Committee, the Department of Justice explained that – while some of the protestors’ actions were illegal under the Criminal Code prior to the invocation of the emergency measures – the Emergency Measures Regulations set out the actions that were being targeted. The Department of Finance clarified that the measures enacted were not retroactive, and that – for example – only those making financial contributions to the protests from 15 February 2022 onwards would be affected. The Department of Justice went on to say that it believed – once enacted – that the assessment as to whether the emergency measures continued to be necessary was being performed on an hourly basis.

Both FINTRAC and the Department of Finance expressed that the emergency measures were meant to discourage people from funding illegal activities. The Department of Finance further expressed that – while account freezing can be done outside of the emergency measures by court orders or other legal processes – in its opinion, the invocation was the only way to effectively end the blockades. When asked about the provision of a legal opinion on the emergency measures’ compliance with the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (the Charter), the Department of Justice explained that it does not normally provide Charter Statements for regulations made pursuant to legislation – such as the Emergencies Act – and that “no legal opinion would be forthcoming in normal circumstances.” Notably, Charter Statements are normally prepared by the Department of Justice for every government bill in order to identify potential effects that a bill may have on rights and freedoms guaranteed by the Charter.

The Department of Justice emphasized that accountability measures are built into the use of Emergencies Act, as well as the orders and regulations. In particular, the Act provides that members of both Houses of Parliament can move motions to amend or revoke an order made under the Act and that a parliamentary review committee must be established under timelines set out in section 62 of the Act. Finally, when the emergency is revoked or has expired, an inquiry needs to be held to look into the circumstances that led to the emergency being declared and the response that was taken.

With respect to the measures taken to suspend the vehicle insurance of protestors, the Department of Finance said that the intent of the program was to dissuade people from using their vehicles to participate in these illegal blockades, and it noted that the possibility of having their insurance suspended may have provided an incentive to stop these behaviours; however, it was unaware if any such suspensions had taken place. Additionally, it explained that while the Société de l'assurance automobile du Québec was not explicitly mentioned in the order, it would still have been required to suspend the vehicle insurance of individuals it knew were involved in the protests.

Proposals related to improvements to the Act or its future use included the Assembly of First Nations, that noted that both overt and covert systemic racism against Indigenous Peoples must be taken into account, while Newton Crypto Ltd. expressed the need for “guardrails” to be placed around separating Canadians from their access to the financial system. The Canadian Bankers Association suggested the future use of “humanitarian exemptions” to certain measures – such as the freezing of joint accounts – where one or more owners of an account were not a designated person under the emergency measures and could be unfairly affected.

Chapter 3: Consumer Protection and Account Freezes

Background

Outside of the Order, financial institutions have legal obligations as part of Canada’s measures to combat money laundering and terrorism financing. These obligations namely include financial institutions and entities engaged in the business of dealing in virtual currencies among the reporting entities that are subject to the reporting requirements provided under the Proceeds of Crime (Money Laundering) and Terrorist Financing Act (PCMLTFA). Reporting entities must implement a compliance program, verify the identity of their customers, carry out other due diligence activities such as “know your client” requirements, as well as keep records related to the accounts and transactions of their customers.

In particular, as part of their compliance program, financial institutions must develop policies and procedures to assess and mitigate their money laundering and terrorist financing risks. A risk assessment may be done using a risk-based approach, which takes into consideration several elements, such as the nature of the business, the customers and/or the business relationships.

Due to the sensitive nature of the information communicated under the PCMLTFA, reporting entities are prohibited from disclosing that they have made, are making, or will make a report pursuant to the PCMLTFA as well as from disclosing the contents of such a report with the intent to prejudice a criminal investigation, whether or not it has begun. This is referred to as the “no tipping-off” rule in Recommendation 21 of the Financial Action Task Force, an independent inter-governmental body established by the G-7 that acts as “the global money laundering and terrorist financing watchdog.”

Finally, it should be noted that cryptocurrency wallets can be “hosted” or “unhosted”. A “hosted wallet” means that a financial institution, cryptocurrency exchange or wallet service hosts the owner’s private cryptographic key. An “unhosted wallet” means that the wallet owner hosts their own private key. Therefore, only hosted wallets are subject to the reporting requirements under the PCMLTFA through the entity that hosts them. Furthermore, certain cryptocurrencies – such as Bitcoin – operate on a decentralized network that enables peer-to-peer exchanges, where users can privately exchange cryptocurrency with one another without the use of an intermediary, which are also not captured under the PCMLTFA as there is no intermediary subject to the reporting requirements.

The Order introduced two additional obligations: an obligation for crowdfunding platforms and payment service providers to register with FINTRAC and report to it (section 4 of the Order), and a duty for financial entities listed in section 3 of the Order to determine, cease dealing and disclose (sections 2, 3 and 5 of the Order).

Specifically, the duty to determine in section 3 of the Order meant that the financial entities had to “determine on a continuing basis whether they [were] in possession or control of property that [was] owned, held or controlled by or on behalf of a designated person.”

A “designated person” was defined in section 1 of the Order as “any individual or entity that is engaged, directly or indirectly, in an activity prohibited by sections 2 to 5 of the Emergency Measures Regulations.” In general, a “designated person” was interpreted as one that was engaged, directly or indirectly, in a public assembly that disrupts trade, critical infrastructure, supports the threat or use of acts of serious violence, and/or an individual that provided property to facilitate or participate in any such assembly.

Witness Testimony

During its study, the Committee heard about how the process of freezing accounts unfolded for financial institutions and entities operating in the cryptocurrency sector, as well as their respective experience in carrying out a risk assessment as required by the PCMLTFA. The Committee also heard whether customers were advised of account freezes and, if so, how.

The Freezing of Accounts

The Canadian Bankers Association, the Department of Finance and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) confirmed that the Order did not apply retroactively, with the RCMP further stating that it had communicated very clearly to the financial entities that the measures were to be applied only while the Order was in effect. The Department also testified that financial institutions started unfreezing accounts as of 21 February 2022. The Department added that the total value of the accounts frozen as a result of the Order was approximately $7.8 million. The Canadian Bankers Association went on to say that any account that remained frozen beyond the date on which the emergency measures were lifted would be as a result of a court order. It also confirmed – based on the numbers provided by the RCMP – that 180 accounts from the largest six domestic banks were frozen as a result of the Order, including a few corporate accounts. However, it was unable to confirm how many of these accounts were held by Canadian entities, as opposed to entities outside of the country.

The Canadian Credit Union Association, in turn, testified that their members had frozen a total of 10 accounts, with a total value of less than half a million dollars.

The RCMP told the Committee that at least 257 accounts were frozen by financial institutions. The RCMP added that it also disclosed information on 57 entities to financial institutions and other listed entities. Furthermore, the RCMP identified and disclosed 170 Bitcoin wallet addresses as receiving funds linked to the HonkHonk Hodl crowdfunding campaign, which raised 20.7 Bitcoin with a value of between $1 million to $1.2 million. Lastly, the RCMP said that it disclosed a number of these cryptocurrency wallet addresses linked to a joint RCMP and Ontario Provincial Police investigation to virtual currency money service businesses and directed these businesses to cease the facilitation of any transaction and to disclose any transaction information to the RCMP.

The Department of Finance explained that the freezing of an account could be initiated by the RCMP’s sharing of the protestors’ names with the financial institutions, or could take place further to the financial institution’s internal processes and verification – carried out through algorithms – to determine whether there were accounts associated with the protests. The RCMP testified that personal information available in the police database was communicated to financial institutions to enforce the Order, including the individual’s sex, height, previous police dealings, and whether the individual was suspected of – or was a witness to – other crimes.

The Department of Finance noted that it was possible that joint accounts be frozen pursuant to the Order, if an individual involved in the protests was co-holder of the account. It also confirmed that more than one account of the same individual involved in the protests could be frozen. The Department also mentioned that it discussed the possibility that child support payments might be disrupted due to the freezing of certain accounts with financial institutions, and advised them that they were able to use their judgment to ensure child support payments were not disrupted.

Wealthsimple remarked that the breadth of the Order put them in a position where it was required to freeze all accounts related to a designated person, including registered accounts, even though it felt it was unlikely that a Registered Retirement Savings Plan could be used to fund an illicit activity. It also highlighted the fact that, as a wealth management and cryptocurrency platform business, it holds assets for customers that are not typically used in the same way as assets held in a financial institution for daily banking activities.

Cryptocurrency Sector

Wealthsimple testified that it froze one account, while Newton Crypto Ltd testified that it did not freeze any. Both Newton Crypto Ltd and Wealthsimple nevertheless blocked certain transactions to Bitcoin wallet addresses identified by the RCMP; however, they were unable to give the value of these transactions. Wealthsimple and Newton Crypto Ltd informed the Committee that they did not see a significant level of transaction activity aimed at funding the protests.

Wealthsimple and Newton Crypto Ltd also confirmed that they ceased screening transactions against the lists received by the RCMP once they received confirmation that the emergency measures were lifted.

Newton Crypto Ltd underlined that it is unable to freeze or hold funds held in private Bitcoin wallets off their platform, as the ability of users to transact peer-to-peer without an intermediary is a key characteristic of Bitcoin. However, Newton Crypto Ltd emphasized that – in many cases – Bitcoin in a self-hosted wallet may be seized as part of a court order as it can be traced to a person. Ether Capital stated that the emergency measures covered both platform and self-hosted wallets, as the platforms were covered explicitly, and an individual using a self-hosted wallet donating to an identified address could be identified on the blockchain. However, Ether Capital and Wealthsimple mentioned that the nature of cryptocurrency does not restrict its use to platforms within Canada’s jurisdiction, making its regulation, use, and consumer protection more complicated.

Ether Capital feared that the negative backlash experienced by the cryptocurrency sector as a result of the emergency measures may lead banks and audit firms to stop offering traditional financial services to the cryptocurrency sector.

Financial Institutions

Both the Canadian Credit Union Association and the Canadian Bankers Association testified that they and their members worked with – and relied on the names provided by – the RCMP to enforce the Order, which were compared with their records to validate if there was in fact activity that warranted the freezing of related accounts.

While acknowledging that it was very challenging to dispute information provided by the RCMP, the Canadian Bankers Association noted that banks were trying to respect the spirit and intent of the Order to ensure that they were only freezing accounts linked to individuals or entities that were understood to be engaged in illegal activities. Finally, it confirmed that banks did not rely on external information, such as leaked donor lists, to freeze accounts.

The Department of Finance reiterated that, in normal circumstances, financial institutions may freeze accounts when they suspect illegal activity, such as fraud or theft, to protect customers in cases of suspicious activity or as part of a police investigation. The department and the Canadian Bankers Association confirmed that accounts may also be frozen pursuant to court orders.

The Canadian Bankers Association testified that, under the Order and separate from information provided by the RCMP, banks were obligated to continue applying their normal risk-based approach in monitoring accounts to make their own determinations as to whether an account needed to be frozen. It further observed that the Order imposed a legal obligation to freeze accounts, whereas financial institutions usually enjoy some discretion in choosing how they handle suspicions of financing of criminal activities.

FINTRAC stated that if a customer exceeds a certain risk level, as established by the financial institution, the financial institution may send a suspicious transaction report to FINTRAC. In such a report, information on the measures taken by the financial institution will be included, which in turn is shared with law enforcement agencies.

The Department of Finance mentioned that, although very unlikely, it was possible that someone who gave a small donation of $20 would be captured and have their bank account frozen. The Canadian Bankers Association clarified that the account would only be frozen if unusual activity had taken place, as determined pursuant to the bank’s risk-based approach.

Notice of Account Freeze

The Department of Finance confirmed that no obligation was imposed on financial institutions to notify their customers of an account freeze, pursuant to the Order or otherwise, while acknowledging that legislating this obligation might be possible.

The Canadian Bankers Association explained that it was up to each bank to determine whether to notify the customer or not, as is the case with court orders. In some cases, customers were notified after the fact and in other cases, they were not notified that their account had been frozen. It stated, however, that if a bank had not notified the customer of an account freeze, it would have provided information to the customer upon request.

The Canadian Credit Union Association mentioned that credit unions notified many customers whose accounts were frozen. Wealthsimple testified that it did not advise its customer whose account was frozen, noting there is “good reason” not to notify clients in these circumstances. Newton Crypto Ltd. noted that in cases where there is an ongoing investigation, it has an obligation not to inform its customer of an account freeze – referred to as the “no tipping-off rule.”

The RCMP and the Department of Finance encouraged customers to communicate directly with their financial institution to answer any question they might have and resolve any issue with regard to the freezing of their account, including in cases of mistaken identity. However, both the Canadian Bankers Association and the Department of Finance testified that they were not aware of any instances where accounts were frozen in error.

The Department of Finance contended that the positive obligation imposed on financial institutions to review the requirements under the Order on an ongoing basis offered adequate protection to customers. Additionally, it reminded the Committee that, pursuant to section 47(2) of the Emergencies Act, the Crown remains liable under current legislation for any damages incurred as a result of the wrongful freezing of an account.

Chapter 4: Businesses and People Impacted by Blockades

Background

According to media reports, the “Freedom Convoy 2022,” generally composed of people across Canada opposed to a variety of policies related to the government response to the COVID-19 pandemic, including vaccination requirements for cross-border truckers, departed from several points across Canada in January 2022. The convoy arrived in Ottawa on 28 January, while other blockades began to form in Coutts Alberta on 29 January, the Ambassador Bridge in Windsor on 7 February, and Emerson Manitoba on 10 February.

Ottawa Police Service estimated that on 5 February 2022, 500 heavy vehicles associated with the demonstration were in downtown Ottawa, seven arrests had been made and 70 traffic violation tickets had been issued in connection with the blockade. On 6 February 2022, the City of Ottawa declared a state of emergency and on 11 February 2022 the province of Ontario also declared a state of emergency due to the ongoing blockades.

The Emergencies Act was invoked on 14 February 2022, and three days later, the Unified Command – in control of policing in Ottawa – created a Secured Area in the downtown core where travel was restricted. The area was delimited by Bronson Avenue, the Rideau Canal, the Queensway, and Parliament Hill. Police checkpoints were set up around the perimeter of the secured area. On 18 February 2022 a police operation in downtown Ottawa began to remove trucks and protesters from downtown streets.

Witness Testimony

On the topic of businesses and people impacted by blockades, the Committee heard about the blockade in the National Capital Region and how the Ambassador Bridge blockade affected supply chains and trade with the United States.

Protests in the National Capital Region

Appearing before the Committee, Invest Ottawa and the Gatineau Chamber of Commerce explained that on 31 January 2022, restaurants, gyms, theatres, museums and cinemas were all set to reopen at 50% capacity in Ontario and Quebec, providing a much-needed opportunity to generate income and to welcome residents back to their businesses after a series of closures due to containment measures related to the COVID‑19 pandemic.

Invest Ottawa explained that the reopening of businesses in downtown Ottawa wasn’t able to take place, because the protestors arrived on 28 January 2022, shutting down the downtown core. Acknowledging that Ottawa was the focal point of the protest and that the situation there was “extreme”, the Gatineau Chamber of Commerce told the Committee that downtown Gatineau was “stormed.” It added that all merchants in downtown Gatineau suffered “incredible losses,” and “serious harm,” as people who came to their businesses refused to follow public health measures.

Invest Ottawa added that the protesters prevented companies from being able to go about their normal business. It stated that some of these businesses were afraid for their employees and were implementing additional security measures in and around the perimeters of their facilities as they could not physically operate there.

In speaking to the Committee about the invocation of the Emergencies Act, Invest Ottawa stated that it did not feel equipped to pass judgment on the usefulness of the Act, but testified that after investing so much time with companies to help them get through the pandemic, it was extremely grateful that the protest was brought to a close.

Discussing a CBC article – which stated that retail experts estimated the total economic cost of the protest for downtown Ottawa to be between $44 million and $200 million from 29 January to 20 February 2022 – Invest Ottawa mentioned that the article did a “very good job of providing a variety of views on what the costs would be.”

Additionally, Invest Ottawa indicated that it will be implementing the government’s business financial assistance programs, with $20 million from the federal government and $10 million from the Ontario government, including an additional $1.5 million is allocated to Ottawa Tourism. It added that companies that experienced financial duress during those three weeks, and were clearly impacted by it, can access to up to $15,000 per company. Invest Ottawa also highlighted that this funding is destined to cover part of the additional business expenses in security, the cost of perishable inventory, and the general costs that a business had to pay even if it could not operate during that period.

The Gatineau Chamber of Commerce expressed its satisfaction with the federal government’s decision to offer Gatineau businesses the same assistance as Ottawa businesses, to be provided through the Canada Economic Development for Quebec Regions agency.

On the topic of mental health, Invest Ottawa stressed that financial duress has been a big stressor for a lot of people, many of whom are still “on the brink.”

Supply Chains and Border Crossings

Figure 1 – Number of Trucks Crossing the Ambassador Bridge per Month

Source: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament using data obtained from the Bridge and Tunnel Operators Association, Ontario Border Crossings with Michigan and New York, accessed on 12 April 2022.

In speaking to the Committee about the blockade of the Ambassador Bridge in Windsor that began on 7 February 2022, the Automotive Parts Manufacturers’ Association (APMA) reiterated that the blockade was publicly disavowed by the Canadian Trucking Alliance and the Ontario Trucking Association, that no long-haul trucks were involved in the blockade at the Ambassador Bridge, that all of the major logistics companies and bonded companies it uses have a 100% vaccination policy for their drivers, and that any unvaccinated drivers were reassigned to intra-country shipments. It also indicated that Canada’s vaccine mandates were a reaction or a reflection of similar American mandates and noted that the cost of trucking had increased by 10% to 15% as a result of vaccine mandates for truckers. The APMA reiterated that it expressed concerns over the effect of the mandates on its industry in November of 2021, but that it accepted “this latest hurdle as something we could absorb for the greater good.”

The APMA emphasized that the automotive industry in Canada is very integrated with that of the United States and explained that on a regular day, about 10,000 truck drivers pick up and deliver $50 million in goods from Canadian parts companies, deliver them to their U.S. customers, and return with a similar load from United States factories to Canadian automakers.

Regarding the impacts of the blockade of the Ambassador Bridge, the APMA testified that the blockade led to the stoppage of production at plants in Michigan, Ohio, Illinois, Kentucky and Tennessee. This cost the highly integrated automotive sector approximately $1 billion in unrecoverable production, and approximately 100,000 Canadian automotive workers faced shift and pay losses. Furthermore, the APMA explained that Canada is currently negotiating with the United States on its electrification plan and the blockade highlighted to American lawmakers that the United States is vulnerable to an interruption of auto parts deliveries from Canada.

Consequently, the APMA advocated for a better mitigation plan amongst all levels of government to prevent similar blockades of critical public infrastructure.

Chapter 5: CrowdFunding

Background

Crowdfunding can be defined as a way for individuals or businesses to collect funds from many people using online platforms. Fundraising campaigns may be created by businesses to raise funds in exchange for financial and/or material rewards, or by individuals or non-profits to raise funds for charitable or other purposes without providing any financial or material return.

GoFundMe is a U.S.-based crowdfunding platform that was founded in 2010. Its terms of service state that GoFundMe is not a broker, financial institution, creditor or charity and that it is simply an “administrative platform” that enables fundraisers to connect with donors. This means GoFundMe does not process donors’ financial transactions and it is not among the entities required under section 5 of the PCMLTFA to report suspicious transactions to Canada’s financial intelligence agency, FINTRAC. Rather, GoFundMe’s third-party payment processors would be captured by the PCMLTFA provision.

Term 8 of GoFundMe’s terms of service prohibits

[u]ser [c]ontent that reflects or promotes behavior that we deem, in our sole discretion, to be an abuse of power or in support of hate, violence, harassment, bullying, discrimination, terrorism, or intolerance of any kind relating to race, ethnicity, national origin, religious affiliation, sexual orientation, sex, gender, gender identity, gender expression, serious disabilities or diseases.

While GoFundMe initially facilitated the crowdfunding for the protests, on 4 February 2022 it announced that it was cancelling the fundraiser because “we now have evidence from law enforcement that the previously peaceful demonstration has become an occupation, with police reports of violence and other unlawful activity.” Having been deplatformed by GoFundMe, the protest organizers reportedly began use of GiveSendGo as a replacement crowdfunding platform.

GiveSendGo’s terms of service are roughly similar to those of GoFundMe in that they prohibit the use of its platform for activities that violate any law, statute, ordinance or regulation related to items “that encourage, promote, facilitate or instruct others to engage in illegal activity [or] promote hate, violence, racial intolerance, or the financial exploitation of a crime.”

Witness Testimony

During its study, the Committee heard about how crowdfunding platforms GoFundMe and GiveSendGo monitor activities on their platform, their involvement in the protests in Ottawa and elsewhere in Canada and their assessment of the origins of the donations in support of these protests. GiveSendGo was invited to participate in the Committee’s study but declined to appear. Accordingly, Committee members did not have the opportunity to question this witness or address its testimony directly. It appeared before the Standing Committee on Public Safety and National Security (SECU) on 3 March 2022, and this testimony has been incorporated into this chapter.

Monitoring of Fundraising Campaigns

GoFundMe, during its appearance before SECU, informed committee members that approximately 20% of its employees are dedicated to compliance activities, including policy monitoring, enforcement, financial crimes preventions and sanctions screening.

In conducting its due diligence of campaigns on its platforms, GoFundMe explained that its employees first focus on the recipient of funds and runs “know your customer” checks, in collaboration with payment processors, to establish the identity of the funds’ recipient and of the owner of the account the funds will be deposited in. It added that payment processors and banks conduct their own due diligence of the funds’ recipient.

With respect to donations, GoFundMe said that it does a risk-based assessment based in part on the nature of the campaign. In the case of the campaign in support of the protests, it explained that it intensified its review of the donations given its “unprecedented” and “fast-moving” nature and the significant impacts that it had, and that it undertook a review of foreign sources of donations.

GiveSendGo indicated that the portion of its resources that it allocates to the verification of campaigns and organizers is similar to that of GoFundMe. It stated that it does not condone violence of any form and that it has processes in place with law enforcement to deal with individuals who commit acts of violence. It mentioned that it uses a certain level of discretion in determining whether fundraising campaigns are related to activities prohibited by its terms of service. It further explained that to the extent that individuals or organizations involved in a campaign are legally authorized to receive payments, that they pass the know your client and anti-money laundering verifications and that the object of the campaign is legal, it would allow the campaign on its platform. As well, it said it believed that protests are fundamental to democracy and added it is very hesitant to limit people’s freedoms based on their political beliefs.

Involvement of Crowdfunding Platforms in the Protests

Crowdfunding platforms GoFundMe and GiveSendGo, as well as other witnesses, provided an account of the involvement of the two platforms in the funding of the protests.

GoFundMe explained that the fundraising campaign for the “freedom convoy” was created on 14 January 2022, subjected to active monitoring on the following day due to its significant level of activity and found, at that time, to be complying with the organization’s terms of service. It made a distribution of $1 million, through its payment processing partner, to the TD Bank account designated by the campaign’s organizer. It noted that TD Bank later applied to the court to surrender the funds that was in the organizer’s account.

GoFundMe stated that it suspended the fundraising campaign on 2 February 2022, thereby pausing all further donations and withdrawals, following certain public statements made by the organizer. Between 2 February and 4 February 2022, it received reports from local authorities of violence, harassment, misinformation and threatening behaviour by a number of individuals associated with the protests. On 4 February 2022, following exchanges with the organizer and her team and further reports from authorities, GoFundMe determined that the campaign was no longer meeting its terms of service, removed it from its platform and initiated refunds to all donors through its payment processing partner, including transaction fees, tips and the $1 million already paid out. On 14 February 2022, it pre-registered with FINTRAC, as required by the Order made under the Emergencies Act.

FINTRAC indicated that following the removal of the campaign from the GoFundMe platform, a new fundraising campaign was created on the GiveSendGo platform. The Department of Justice stated that, at the request of the Ontario government, a court order was issued on 10 February 2022 to freeze the two main crowdfunding accounts on the GiveSendGo platform and that the order was enforced under existing Canada-United States co-operation agreements with respect to financial crime.

During its appearance before SECU, GiveSendGo said that about 6% of all of its fundraising campaigns originate out of Canada and that it had never hosted campaigns of a political nature of this scale before. It told the Committee that it saw these protests as largely peaceful and that it was unaware that a number of protesters called for violence and overthrowing the government. It clarified that the campaigns on GiveSendGo were not connected to the blockade of the Ambassador Bridge. The crowdfunding platform added that it was never contacted by Canadian authorities to end the fundraising campaign for the protests and that it heard about the protests from the media and other indirect sources. It noted that it learned about the Ontario court order on social media. According to GiveSendGo, Canadian authorities should be more proactive in reaching out to those they believe may be committing offences.

Regarding the funds frozen by the Ontario court order, GiveSendGo said on 3 March 2022 that they are being held in a U.S. bank account. It added that it is examining options going forward and that it intends to send the funds to the campaign recipient, if possible. If not, donors would be refunded. Furthermore, GiveSendGo informed SECU members that it had been the subject of a cyber attack during the course of the campaign and that it allocated additional resources to prevent the reoccurrence of such attacks on its platform.

Origins of Donations

GoFundMe told the Committee that it conducted a review of the origin of the donations made in connection to the campaign in support of the protests on its platform. It explained that it worked with its payment processing partners and related financial institutions to assess the sources of donations based on the financial instruments that were used, noting, for example, that each credit card has a Bank Identification Number associated with it. It clarified that collecting information beyond the issuing bank and the payment instrument would be quite complex and would have to be done by the bank itself.

GoFundMe found that 88% of the donated funds originated in Canada and that 86% of donors used Canadian banks or credit cards; however, the information it receives is self-reported from donors and it relies on the banks and credit cards to confirm the identities of these individuals. It noted that a small number of donations were from Russia but that, in its opinion based on the evidence that it saw, there was no coordinated effort with respect to these donations. According to it, the largest single donation was in the amount of $30,000 and was made by a Canadian.

GiveSendGo indicated that 60% of donors and amounts donated through its platform in support of the protest were from Canada and that 37% were from banks or credit cards located or issued in the United States. It added that most donations were under $100.

In response to the Committee’s concerns about the protest’s funding, especially regarding certain donations from foreign sources, the RCMP said that it can only share limited information because an investigation on the subject is ongoing.

The Assembly of First Nations remarked that the financing of the “protests and blockades highlighted the vulnerability of Canada to be influenced by national and international white supremacists and far-right extremist groups.”

Chapter 6: Financial Intelligence and Regulation

Background

Established by the PCMLTFA and its regulations, FINTRAC is Canada’s financial intelligence unit. It collects financial intelligence and enforces compliance of reporting entities with the legislation and regulations. FINTRAC acts as a unique partner in Canada’s anti–money laundering and anti–terrorist financing regime that is led by the Department of Finance. FINTRAC is established as a financial intelligence agency independent from the law enforcement agencies and has no investigative powers. It is authorized to share financial intelligence with law enforcement agencies – that may go on to investigate the occurrence of money laundering or terrorist financing – as well as other departments with distinct roles under the regime. Within Canada’s regime, FINTRAC undertakes the following:

- receives financial transaction reports and voluntary information in accordance with the legislation and regulations;

- safeguards personal information under its control;

- ensures compliance of reporting entities with the legislation and regulations;

- maintains a registry of money services businesses in Canada;

- produces financial intelligence relevant to investigations of money laundering, terrorist activity financing and threats to the security of Canada;

- researches and analyzes data from a variety of information sources that shed light on trends and patterns in money laundering and terrorist activity financing; and

- enhances public awareness and understanding of money laundering and terrorist activity financing.

FINTRAC defines terrorist financing as the act of providing funds for terrorist activity. This may involve funds raised from legitimate sources such as donations from individuals, businesses and/or charitable organizations that are otherwise operating legally. Or it may involve funds from criminal sources such as the drug trade, the smuggling of weapons and other goods, fraud, kidnapping and extortion.[1]

Under section 4(1) of the Order, additional entities were required to register with FINTRAC if they were in possession or control of property owned, held or controlled by or on behalf of a designated person.

The additional entities that were required to register with FINTRAC under the Order are the following:

- entities that provide a platform to raise funds or virtual currency through donations; and

- entities that perform any of the following payment functions:

- the provision or maintenance of an account that, in relation to an electronic funds transfer, is held on behalf of one or more end users,

- the holding of funds on behalf of an end user until they are withdrawn by the end user or transferred to another individual or entity,

- the initiation of an electronic funds transfer at the request of an end user,

- the authorization of an electronic funds transfer or the transmission, reception or facilitation of an instruction in relation to an electronic funds transfer, or

- the provision of clearing or settlement services.

Under the Order, these entities were required to report suspicious or large value transactions to FINTRAC.

With respect to the oversight of crowdfunding platforms and the payment service providers the Deputy Prime Minister remarked that the “government will also bring forward legislation to provide these authorities to FINTRAC on a permanent basis.”

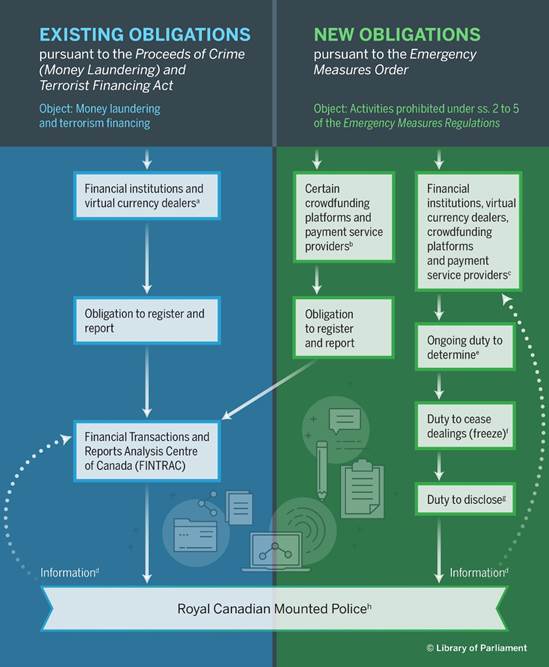

Figure 2 – Summary of Financial Entities’ Obligations to Gather and Report Information Pursuant to the Proceeds of Crime (Money Laundering) and Terrorist Financing Act and the Emergency Economic Measures Order

Notes: a. Other reporting entities are listed under section 5 of the PCMLTFA.

b. If it was in possession or control of property linked to a designated person (section 4(1) of the Order).

c. Other entities were also subject to these obligations pursuant to section 3 of the Order.

d. Additional authorized disclosure recipients are provided under the PCMLTFA and the Order.

e. The ongoing duty to determine provided under section 3 of the Order imposed an obligation on entities to “determine on a continuing basis whether they are in possession or control of property that is owned, held or controlled by or on behalf of a designated person.”

f. The duty to cease dealings is provided under section 2 of the Order.

g. This duty applies to the existence of property or transactions linked to a designated person.

Witness Testimony

Appearing before the Committee, witnesses highlighted the operations of FINTRAC and its role under the emergency measures, the workings of certain cryptocurrency platforms, the financial intelligence that could be gathered from crowdfunding platforms and payment service providers, as well as how these businesses are currently – or could be – regulated.

In its testimony to the committee, FINTRAC underscored that its mandate was not expanded by the emergency measures, only the entities that would report to it, and that the scope of these reports is limited to money laundering and terrorist financing activity. With respect to receiving intelligence on donations to crowdfunding platforms, FINTRAC went on to say that – absent the emergency measures – anytime such a platform was used, “there would be a touchpoint at a financial institution. There would be a requirement, if [an individual was] setting up a page or if [they] were receiving the donations in order to disburse them to others, for a touchpoint at a bank. There would be a financial institution in a position as a reporting entity to report transactions to us if they were threshold transactions or if there were reasonable grounds to suspect that the transactions were relevant to a money-laundering or terrorist-financing activity.” GoFundMe confirmed that it does not directly interact with, or hold any funds collected from donors – and is unable to redirect those funds – as donations are processed, held and paid out by its payment processing partners that are already regulated by FINTRAC.

FINTRAC reminded the Committee that it was established as an administrative financial intelligence unit for matters related to money laundering and terrorist financing, not a law enforcement or investigative agency. As a result, it does not have the authority to monitor or track financial transactions in real time, freeze or seize funds, ask any entity to freeze or seize funds, or cancel or delay financial transactions. This was done very deliberately by the Parliament of Canada to ensure that it would have access to the information needed to support the money laundering and terrorist financing investigations of Canada's police, law enforcement and national security agencies, while protecting the privacy of Canadians.

FINTRAC confirmed that it was not involved in any way in the freezing of accounts as a result of the information provided to the financial institutions by the RCMP. It further testified that the account freezes were done without its knowledge. It also highlighted that once an account was frozen, there were no transactions to report to FINTRAC.

The Department of Finance and FINTRAC explained that – prior to the Order – crowdfunding platforms, payment service providers, and certain cryptocurrency platforms did not report to FINTRAC, so requiring them to do so would help mitigate the fact that these platforms might receive illicit funds as well as increase the quality and quantity of financial intelligence received by FINTRAC, which would also support the investigations of law enforcement. FINTRAC clarified that these groups were only required to register with them if they were in possession or in control of property that was owned, held or controlled by an individual or entity who was engaged in an activity that was prohibited in the Emergency Measures Regulations, that this requirement ended with the revocation of the emergency measures, and any entities already registered with FINTRAC would already have to report on activities covered under the Order. Wealthsimple went on to say that cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin are already fully transparent, as every transaction is recorded on a public blockchain.

FINTRAC also indicated that – while provincial regulators may address certain aspects of crowdfunding platforms, payment service providers, and certain cryptocurrency platforms – it was not a duplication of efforts to require that they also report to it. Furthermore, it works closely with provincial counterparts with respect to information‑sharing agreements, employee training and best practices. FINTRAC also highlighted that it undertakes considerable educational outreach with financial institutions regarding compliance measures, ensuring they understand the critical role they play in disrupting and mitigating the damage of financial crime.

With respect to the regulation of crowdfunding platforms, GoFundMe believed that there are no existing Canadian laws or regulations that directly regulate peer-to-peer crowdfunding, and that – internationally – the regulation generally falls on the organizer of the fundraiser, who may be required to seek permits or government approval before the fundraising commences. In particular, Australia, Denmark and Finland take this approach. In other jurisdictions, like Singapore, there are voluntary codes of practice that online fundraising platforms are asked to adhere to that outline best practices for protecting users. In Romania, regulations are placed on the donors of crowdfunding campaigns with respect to the amount of the donation.

FINTRAC confirmed that it had sufficient capacity to meet the requirements of the emergency measures, and that it was able to react quickly to the measures on their website and in addressing the questions of reporting entities.

The Department of Finance confirmed that FINTRAC cannot request information from reporting entities, and that FINTRAC was accordingly not communicated with in these regards, as it was outside its mandate. FINTRAC also re-iterated that it does not monitor foreign transactions, though it does share information with international counterparts who may forward information on suspicious or high value transactions into Canada from abroad. Similarly, the agency does not use data from data leaks and did not receive a list of people who donated to the protest, as this is outside its mandate.

Speaking on cryptocurrency, FINTRAC explained that while virtual currency dealers[2] are subject to its regular reporting requirements, peer-to-peer cryptocurrencies are not. The addition of virtual currency dealers came in 2020 and 2021, and FINTRAC can now see the whole continuum of fiat and virtual currencies, which was very helpful in fulfilling its mandate. FINTRAC also pointed out that it was receiving excellent information from virtual currency dealers – such as with respect to its public-private partnership to combat child sexual exploitation material on the Internet – and that the suspicious transaction reports it receives have debunked the idea of anonymity in virtual currency.

Regarding the extent to which crowdfunding platforms and payment service providers registered with FINTRAC, the agency noted that limited progress could be made in the short time the emergency measures were in effect, but that organisations that had pre-registered with FINTRAC would have been able to report on suspected money-laundering or terrorist-financing activity. Similarly, FINTRAC was unable to assess best use – or the value of – the reports that would come from crowdfunding platforms during the period the measures were in effect, but would continue to explore this matter. It went on to mention that many of the crowdfunding platforms have fairly strong anti-money laundering and anti-terrorist financing compliance programs in place, as they do not want to be misused by organizers and donors.

While the emergency measures were in place, FINTRAC mentioned that there was neither a significant decline nor increase in reporting, though the expansion of reporting entities may have reinforced the fact that it was illegal to try to donate money to support the protest, so it only played an indirect role in brining the protests to an end. It clarified that “supporting or disbursing the funds related to an illegal blockade has nothing to do with money laundering or terrorist financing. [FINTRAC] would not get a suspicious transaction report [from this activity].”

With respect to making crowdfunding platforms and payment service providers permanently subject to FINTRAC reporting requirements, the Department of Finance noted this could be accomplished either by legislative or regulatory amendments, that it would not impact the ability of Canadians to legally donate money through crowdfunding platforms in the future, that it would fill an information void at the federal level, and that it is working closely with the Department of Justice and FINTRAC to move this forward. The RCMP stated that this change should be made permanent, as it is important that FINTRAC has real time information on these platforms. FINTRAC observed that it has an obligation to look at emerging trends and to evolve as the technology evolves, but that it was difficult to say where the current gaps in legislation are located, and that it is possible that it would not receive many reports from crowdfunding platforms due to the nature of their businesses.

Speaking on potential changes to the kinds of information it receives or those who might report to it, FINTRAC remarked that it is constantly reassessing its understanding of where the risks of money laundering and terrorist financing activity are located, and how to best assess those risks using the reporting it receives. Furthermore, FINTRAC noted that it is constantly considering potential loopholes and vulnerabilities under its mandate, and that any improvements it would recommend would be based on its experiences and international best practices.

Chapter 7: Government and Departmental Communication

Background

The Order introduced a number of obligations on financial institutions and other financial services providers as discussed in Chapter 1. Prior to and after the coming into force of the Order, federal government entities communicated with financial services providers, including at information briefings, to assist them in the application of the measures contained in the Order.

Witness Testimony

With respect to the flow of communication prior to, and during the application of the Order, witnesses clarified the application of the Order, spoke about the levels of engagement with different businesses, and the desire for further direction to be provided in the future.

With respect to enacting the emergency measures, a number of witnesses commented on what information was provided to the businesses that would carry out certain aspects of the Order. The Department of Finance explained that the Order was written in a manner that makes it clear that the financial institutions were responsible for its implementation, and while the Department did not provide financial institutions with written information or instructions with regard to the enforcement of the Order, it confirmed that it was available to answer their questions. It added that it was in contact with the financial institutions, including the Desjardins Group – sometimes on a daily basis – to discuss the order and to answer their questions regarding its implementation. In addition, the Department and the Canadian Credit Union Association highlighted the information sessions that were held for the affected financial institutions, wherein over 620 individuals participated and included over 220 credit unions. With respect to the information provided by the government and the implementation of the Order, the Canadian Bankers Association reported that the in-house counsels of the financial institutions would have reviewed the information.

The RCMP testified that it remained in constant communication with financial institutions for the duration of the Order to ensure that they were provided with the most up-to-date information possible on the status of persons and entities of interest so that they could make the most informed determination possible before taking action to freeze, or unfreeze, financial products. The Canadian Credit Union Association expressed their belief that the six largest Canadian banks were consulted or informed days before credit unions and other financial institutions, and that its members should have equal treatment in matters that directly impact their operations and members, particularly in a time of crisis. Furthermore, when the measures were first announced, its members were very unclear as to whom the financial sanctions applied, which led to some degree of panic among some Canadians that their accounts may be frozen. Many of its members expressed concerns, and many Canadians made significant withdrawals from credit unions as a result, sometimes in the hundreds of thousands of dollars, and on a few occasions, millions. While these withdrawals did not cause liquidity issues for credit unions, better and much clearer communications from the government could have mitigated this. In contrast, the Canadian Bankers Association testified that it did not observe any material change in the withdrawal activity in the days following the invocation of the Emergencies Act, but mentioned that clearer information from the government and/or appropriate authorities from the beginning would have been helpful.

Similarly, the National Chief of the Assembly of First Nations, RoseAnne Archibald, insisted that she was not provided appropriate notice of the emergency measures, and that there should be greater engagement with First Nations on the deeper implications of the Act and its invocation. The National Chief went on to say that while she “really appreciate[s] the relationship [she’s] built with Minister Miller, giving the national chief a heads-up the day before is not acceptable. There need to be processes in place that are definitely more fulsome than that when it comes to first nation land defenders and water defenders.”

With respect to the level of discretion provided to financial institutions regarding whose accounts to freeze, the Canadian Credit Union Association went on to say that its members would have appreciated further guidance from the government in this regard to prevent an uneven application of the Order.

The RCMP explained that it did not discuss with financial institutions how they would freeze or manage the accounts in question, only how the information would be communicated to them. It also shared that – in relation to the emergency measures - its communication with the government took place at various levels, with the commissioner and through a number of government programs.

Wealthsimple and Newton Crypto Ltd. also expressed that they did not have same level of communication with the Department of Finance as Canadian banks – and had great difficulty interpreting the Order – but felt certain notices provided by the RCMP were helpful in fulfilling the Order. Wealthsimple added that the government should increase efforts to engage with companies other than the largest financial institutions – as millions of Canadians now own cryptocurrency. The RCMP offered that additional guidance should be provided to financial institutions as to what to do with cryptocurrency once it has been frozen, namely when such assets fluctuate in value.

The Canadian Credit Union Association observed that, as financial institutions manage their own risk portfolios based on their relationships with their customers, any direction from the government on how information gathered and received during the enforcement of the Order may be used in the future should provide some flexibility. It noted that this is especially true for credit unions, as they tend to be smaller organizations with closer relationships with their customers.

Finally, the Department of Finance recalled that insurance companies were not given instructions in writing with respect to the suspension of vehicle insurance policies, and for its part, FINTRAC stated that it was provided the necessary information with respect to compliance and the businesses that would be required to register with it.

Chapter 8: Law Enforcement

Background

When the Order was in place, all financial institutions were required to disclose the existence of property in their possession or control that they had reason to believe was owned or held by individuals involved in prohibited activities, as well as any information about a transaction or proposed transaction in respect of said property, to the Commissioner of the RCMP or to the Director of the Canadian Security Intelligence Service without delay. Furthermore, any Government of Canada, provincial or territorial institution could disclose information to any financial institution if it was satisfied that the disclosure would contribute to the application of the Order.

The Order does not contain any enforcement provisions. Therefore, no charges were laid by the RCMP under the Order.

Witness Testimony

With regard to law enforcement, Committee witnesses focused mainly on the RCMP’s involvement, the scope of the Emergencies Act, information gathering and their belief in the necessity of invoking the Act.

The Royal Canadian Mounted Police’s Involvement

The RCMP told the Committee that it was clear that the Ottawa Police Service had jurisdiction over the protest in downtown Ottawa in the three weeks leading up to the triggering of the Emergencies Act. The RCMP added that, during that period, its role was to provide advice and support to the federal government – nothing more. The RCMP said that it provided the government with recommendations on certain points, but did not ask for the Emergencies Act to be invoked.

The RCMP told the Committee that there was nationwide concern and monitoring as there was a risk of blockades appearing across Canada. The RCMP was closely following the situation in the National Capital, at the Ambassador Bridge in Windsor; in Coutts, Alberta; and in Emerson, Manitoba.

Scope of the Emergencies Act

Without offering any specifics, the RCMP told the Committee that as soon as the Emergencies Act was invoked, the RCMP reviewed the Act and looked at how it could apply the Act and other measures. The RCMP said that the scope of law enforcement was really limited to the people – the entities – who influenced the protests and were very active, in addition to the truck drivers or companies that were not moving out of downtown Ottawa. The RCMP added that it enforced the law as it was passed, and that the methods it employed were for the sole purpose of clearing downtown Ottawa as peacefully as possible. The Department of Finance reiterated that the purpose of the financial measures was solely to ensure that people stopped funding illegal activities, not to respond to a more ongoing threat to national security.

According to the RCMP, the only additional power that law enforcement received from the Emergencies Act was the ability to share information with financial institutions. The Canadian Bankers Association added that when banks received information from the RCMP on their clients, they looked in their system and had a legal obligation to freeze the accounts of any of their clients who were involved in activities prohibited by the Order.

The RCMP said that it served as a point of contact with financial institutions, sending them information provided by the Ontario Provincial Police and the Ottawa Police Service as well as its own information. The RCMP also said that during the eight days that the Order was in place, it disclosed information on numerous entities to banks, the Canadian Bankers Association, the Investment Industry Regulatory Organization of Canada, the Canadian Securities Administration, credit unions and the Mutual Fund Dealers Association.

Witnesses told the Committee that they did not know whether, barring the RCMP, other federal, provincial or territorial institutions were in direct communication with financial institutions to tell them whether certain individuals had violated the Order. The Department of Finance confirmed that this was possible as prescribed under section 6 of the Order, adding that section 5 requires financial institutions to disclose any relevant information to the Commissioner of the RCMP without delay.

Information Gathering

The RCMP told the Committee that it worked closely with municipal and provincial partners to collect relevant information for the duration of the Order with regard to persons, companies and vehicles directly or indirectly involved in the illegal activities relating to the blockades, in particular, the owners and drivers of vehicles who did not want to leave downtown Ottawa.

The RCMP added that it generally attempted to contact individuals in order to ascertain where they were before providing the information to financial institutions, except for those who had overwhelming evidence against them that they were participating in the designated offence. In addition, the RCMP said that 15 entities were provided by the Ontario Provincial Police and the Ottawa Police Service.

Impacts of the Emergencies Act

Speaking about the effectiveness of the Emergencies Act, the RCMP told the Committee that when it started giving the names of entities to the financial institutions, and when the institutions started to freeze accounts, some people left downtown Ottawa out of a fear that their accounts would be frozen.

The RCMP added that the Emergencies Act allowed law enforcement and monitoring agencies to work more closely, share information with Canadian financial institutions and use financial measures to strongly encourage individuals to leave the illegal protests and deter the counselling of others to commit related criminal offences.

According to the RCMP, although there is legislation under which the RCMP can obtain the power to demand that financial institutions freeze accounts through a court order, the Emergencies Act allowed it to take action faster. The RCMP said it believed that the Emergencies Act was necessary to enable law enforcement to discourage people from maintaining their involvement in the illegal protest, and also to give the power to financial institutions to freeze accounts.

Witnesses disagreed on the need for emergency legislation. With respect to the best way to have put an end to the blockade of the Ambassador Bridge, the APMA stated that there were existing laws that law enforcement could have used. According to it, the municipal and provincial law enforcement agencies that dealt with the roads leading to the Ambassador Bridge appeared paralyzed. It outlined that it was in direct contact with officials at all three levels of government and implored them to terminate the blockade.

The APMA also told the Committee that the Ambassador Bridge was cleared under orders from an injunction that it sought on 11 February 2022, as a plaintiff in superior court in Windsor and then, a day later the City of Windsor and the province joined the injunction. It is of the opinion that the Highway Traffic Act should have been enforced, which would have addressed this crisis right when it started.

Chapter 9: Rights and Freedoms

Background

According to the preamble, the Emergencies Act authorizes the “Governor in Council … subject to the supervision of Parliament, to take special temporary measures that may not be appropriate in normal times” which nonetheless remain “subject [namely] to the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms and the Canadian Bill of Rights.”

The Charter guarantees many rights and freedoms, namely fundamental freedoms, which include: the freedom of opinion, expression, and of peaceful assembly; as well as legal rights, which include: the right to life, liberty and security of the person and the right to be secure against unreasonable search or seizure. The Charter also provides that it does not abrogate or derogate from any aboriginal, treaty or other rights or freedoms that pertain to the aboriginal peoples of Canada.

However, recognizing that limits may be justified in a free and democratic society, the Charter allows reasonable limits to be prescribed by law and, in the case of the right to life, liberty and security of the person, in accordance with the principles of fundamental justice. A balancing exercise therefore takes place between the protection of individual rights and freedoms and society’s interests.

As the Charter is enshrined in the Constitution, which is the supreme law of Canada, any law that is inconsistent with its provisions may be declared by a court to be invalid, in whole or in part. In addition, any person whose rights or freedoms have been infringed or denied may apply to a court to obtain such remedy as the court considers appropriate and just in the circumstances.

Finally, two main federal laws protect the privacy of individuals and customers: the Privacy Act and the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Document Act (PIPEDA). While the Privacy Act applies to personal information about individuals held by government institutions, PIPEDA namely applies to private-sector organizations with regard to personal information they gather “in the course of for-profit, commercial activities across Canada” as well as to the “personal information of employees” held by businesses operating in a federally regulated sector. There are also provincial laws, which may apply in lieu of PIPEDA to businesses in the private sector, and sector-specific privacy laws, such as the Bank Act, that deal with the use and disclosure of personal financial information.

Witness Testimony

During its study, the Committee heard about witnesses’ concerns regarding the invocation of the Emergencies Act on Indigenous Peoples’ treaty, aboriginal and inherent rights and on customers’ right to privacy, as well as the steps that were taken in the drafting of the order and regulations to mitigate adverse effects on individuals’ rights and freedoms.

The Department of Finance contended that the emergency measures complied with the Charter. As explained by the Department of Justice, the emergency measures were drafted with the Charter in mind and tailored to limit any impact on individuals’ rights only to what was reasonably necessary, which the Charter allows.

The Department of Finance reminded the Committee that the financial institutions had a positive obligation to review the requirements under the Order on an ongoing basis. It asserted that this obligation ensured the compliance of the emergency measures to the Charter. Both the Department of Finance and the Department of Justice stressed that once the behaviour prohibited by the emergency measures stopped, an account could be unfrozen.

The Assembly of First Nations stated that First Nations are not extremist groups nor terrorists. It also expressed its concerns about the long-term implications of the emergency measures, namely that the Emergencies Act might be immediately invoked in cases where First Nations are involved in civil actions to protect their treaty, aboriginal and inherent rights. It voiced its belief that emergency measures should not be used as a tool to suppress issues around First Nations’ claiming of their rights to land and water, in particular, and to self-government, while pointing out that what it referred to as Canada’s history of suppressing, oppressing and repressing First Nations people, is a story rarely told.

The Assembly of First Nations was also specifically concerned about First Nations people having their bank accounts frozen or having financial services being temporarily and selectively denied to them as a result of the emergency measures, in light of what it described as the systemic racism that already exists within the financial institutions, law enforcement agencies and within the government. It felt that the protesters were provided with considerable leniency at the outset because they were non-Indigenous and were not initially considered to pose a threat. It urged the need to treat First Nations people with dignity and respect when they take part in civil actions and express disagreement with the government on legislation and policies.

Both the Assembly of First Nations and the Department of Finance expressed that the right to privacy was of particular concern. The Department of Finance further explained that the Order allowed for information to flow from the RCMP to the financial institutions directly, without it having access to the information. The Department of Finance also confirmed that the government did not direct the financial institutions on how to retain the information they received from law enforcement under the Order, while pointing out that there are already laws in place governing the retention of information, which the Canadian Bankers Association confirmed. Finally, the Department of Finance and FINTRAC told the Committee that the enforcement of the Order had not resulted in the creation of a new “no fly list”, insisting that there is no lasting black mark on individuals whose accounts have been frozen.

FINTRAC stressed that it did not have the power, under the emergency measures, to order a financial institution to do something it otherwise cannot legally do. As such, information received by a financial institution from the RCMP could not be used to file a suspicious transaction report with FINTRAC, as law enforcement agencies cannot direct a financial institution to provide information to FINTRAC and FINTRAC could not compel a financial institution to file a suspicious transaction report. As well, it added that information disclosed and received by FINTRAC remained subject to its legislation and the Privacy Act, and when the emergency measures were revoked, all activity associated with information received as part of the emergency measures stopped.