ENVI Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

The Impacts of a Ban on Certain Single-Use Plastic Items on Industry, Human Health and the Environment in Canada

Introduction

Between 12 April and 5 May 2021, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development (the Committee) studied the Government of Canada’s announced intention to regulate plastic manufactured items using the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 (CEPA), and to ban certain single-use plastic items. The Committee undertook this study to examine, among other things, the impacts that the federal government’s approach might have on Canadian small business and the plastics industry, on the environment, and on human health. The Committee heard from witnesses on various topics, including the present operations and the possible future of the Canadian plastics industry, the impacts of plastic pollution on the environment and human health, and how the Government of Canada intends to manage plastics in the future.

The Committee thanks the witnesses for their contributions, and is pleased to present its final report, which includes the study’s findings and recommendations to the Government of Canada.[1]

A Plastics Primer

Plastics can be divided into two main categories: thermoplastics and thermosets. Thermoplastics make up about 75% of worldwide plastics production and can be melted and re‑formed fairly easily.[2] Thermosets, on the other hand, cannot be re-melted once they have been cooled, which makes them strong, but difficult to recycle.[3] Plastics offer many beneficial properties—including insulation, flexibility and resistance to high temperatures, chemicals and shattering[4]—while being inexpensive and easy to produce.

Plastic products are all made from pellets or flakes of plastic, known as plastic resin. Resins can either be made from raw materials—creating what are known as “primary” or “virgin” resins—or from recycled plastic. Nearly all plastic resins are made from fossil fuels: Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) estimates that 90% of new plastic products are derived from fossil fuel feedstocks.[5] An energy-intensive process is required to create these feedstocks, which are then converted into polymer resins, which are in turn made into plastic products. Overall, it takes less energy to produce recycled, or “secondary,” resins, compared to virgin resins. However, recycled plastics do not necessarily cost less money. Firstly, recycled plastics have higher labour costs than other plastics. Also, because virgin resins are mostly made from fossil fuels, they are usually cheaper to produce when the price of fossil fuels is low.[6]

Table 1 presents common types of plastic according to their Resin Identification Code, or RIC. These codes may be familiar to many Canadians: the RIC is the number that appears on the bottom of many plastic packages.

Table 1: Common Types of Plastic

Resin Identification Code |

Type of Plastic |

Products Commonly Made from this Plastic |

1 |

Polyethylene terephthalate (PET or PETE, also called polyester) |

|

2 |

High-density polyethylene (HDPE) |

|

3 |

Plasticized polyvinyl chloride or polyvinyl chloride (PVC) |

|

4 |

Low-density polyethylene (LDPE) |

|

5 |

Polypropylene (PP) |

|

6 |

Polystyrene (PS) |

|

7 |

Other (material made with a plastic resin other than the six listed above, or a combination of multiple resins) |

|

Source: Table prepared by the Committee using data obtained from the American Chemistry Council, Plastic Packaging Resins.

Plastics in Canada

Production

Plastics production is a significant part of the Canadian manufacturing sector. According to a report commissioned by ECCC, the manufacturing of plastic resins and plastic products in Canada was worth an estimated $35 billion in 2017. This amount represented approximately 5% of sales in the Canadian manufacturing sector, employing 93,000 people across 1,932 establishments.[7] These establishments fall into two main categories: large multinational firms that produce raw plastic resins and smaller firms that convert these resins into plastic products.[8]

Single-use plastics—plastics that are used only once before being disposed of or recycled—represent a significant share of the products produced by the plastics industry. According to the Chemistry Industry Association of Canada (CIAC), annual sales of Canadian single-use plastics are worth $5.5–$7.5 billion, and those sales represent between 13,000 and 20,000 direct jobs, and as many as 26,000 to 40,000 indirect jobs. CIAC noted that these jobs are spread across nearly 2,000 firms, of which approximately 60% are in Ontario, 25%–30% are in Quebec, and most of the remainder are in Alberta and British Columbia, with a small number in other provinces.[9]

Canada’s plastics industry mainly produces “virgin” resins, also known as “primary” plastics, in contrast with “secondary” plastics, which are made from recycled plastic.[10] In 2016, 256,000 tonnes of plastic were recycled in Canada, while almost 20 times more virgin resin was produced in the same period.[11]

Use

Plastics are used throughout the Canadian economy. Their single largest end use is for packaging, followed by building and construction materials, and then for parts in the automotive sector.[12] Witnesses drew the Committee’s attention to certain uses of plastics. John Galt, President and Chief Executive Officer at Husky Injection Molding Systems Ltd. pointed out that plastics make up 73% of the value of raw materials in disposable medical devices, which have been particularly crucial during the COVID‑19 pandemic.[13] Likewise, plastics can play a role as Canada transitions to a lower-carbon economy. Bob Masterson, President and Chief Executive Officer of CIAC, explained that the light weight of plastics makes them a useful component in vehicles, allowing cars and aircraft to use less fuel and produce fewer emissions.[14]

Single-use plastics also have many applications. They are especially widely used in food packaging because they can meet food safety standards and help extend the shelf life of food products.[15] In health care, single-use plastic products have enabled innovation and decreased the risk of cross-contamination.[16]

Given its widespread use, plastic will be produced in ever greater quantities in the coming years. Manjusri Misra, Professor and Tier 1 Canada Research Chair in Sustainable Biocomposites at the University of Guelph, told the Committee that the world will make 1 billion tonnes of plastics a year by 2050, more than doubling the current production of 450 million tonnes a year. Approximately half of plastics produced today are single-use plastics.[17]

Disposal

In Canada, most plastic becomes waste. Of all the plastic used in the country in 2016, about 70%—roughly 3.3 million tonnes—was disposed of as waste. Of this amount, ECCC estimated that 86% was sent to landfill.[18] Similarly, the Canada Plastics Pact estimated that, of the 1.9 million tonnes of plastic packaging produced in Canada, 88% is landfilled or incinerated.[19]

As the Committee heard, Canada’s widespread landfilling of plastic waste represents a lost economic opportunity.[20] In 2016, landfilled plastic waste represented approximately $7.8 billion of material that could have been put to other uses.[21] Only a small part of the plastic used in Canada is recycled. According to ECCC, in 2016 approximately 9% of all plastic waste was recycled.[22] George Roter, Managing Director of the Canada Plastics Pact, said that plastic packaging is recycled at a slightly higher level: about 12%.[23]

Certain kinds of plastics are more widely recycled than others. Beverage containers, for example, are recycled at high levels.[24] Witnesses noted that these containers are more commonly recycled partly because they are made of more easily recyclable plastics, like PET, but also because of the existence of collection and deposit programs in some provinces.[25] Deposit programs encourage consumers to recycle the material, while collection programs help recyclers secure more supply of recyclable material.

However, in most cases the inverse situation applies, as Norman Lee, Director of Waste Management at the Regional Municipality of Peel, explained:

One of the most significant waste management challenges faced by municipalities today is the recycling of plastic packaging, which is becoming lighter and more complex, making it more difficult and more expensive to manage. The lack of mandatory recycled content requirements results in weak demand for some recovered plastics, such as the plastic film used in grocery bags. Messages from brand owners and retailers often conflict with municipal messaging about what can be recycled or composted. This results in materials being put in the wrong bin, which increases cost and decreases diversion.[26]

The Committee heard that the Government of Canada could play a role in increasing the rate of plastic recycling across Canada, as described in the “Reuse and Recycle” section of this report. Table 2 presents the roles of federal, provincial and municipal governments in waste management.

Table 2: The Roles of Federal, Provincial and Municipal Governments in Waste Management

Government |

Roles |

Federal |

|

Provincial |

|

Municipal |

Overseeing the following steps in the management of household waste:

|

Source: Table prepared by the Committee based on information from Government of Canada, Municipal solid waste: a shared responsibility; and Government of Canada, Management of hazardous waste and hazardous recyclable material.

The Government of Canada’s Proposed Ban on Certain Harmful Single-Use Plastics

The Government of Canada’s Approach

On 23 September 2020, in the Speech from the Throne, the Government of Canada announced that it would “ban harmful single-use plastics next year.”[27] The following month, in October 2020, the Government of Canada published a science assessment that examined how plastic pollution affects the environment and human health.[28] The government also issued a discussion paper proposing how the federal government would manage plastic waste and pollution.[29] This paper indicated that, to reach “zero plastic waste” by 2030, the government would:

- manage single-use plastics, including banning or restricting certain single-use plastics that cause harm, where warranted and supported by scientific evidence

- establish performance standards for plastic products to reduce (or eliminate) their environmental impact and stimulate demand for recycled plastics, and

- ensure end-of-life responsibility, so that companies that manufacture or import plastic products or sell items with plastic packaging are responsible for collecting and recycling them.[30]

In support of this agenda, the Government of Canada intends to use its power under CEPA to regulate plastics. Helen Ryan, Associate Deputy Minister of the Environmental Protection Branch at ECCC, explained that:

[Regulating certain plastic manufactured items under CEPA] will allow the government to enact regulations to change behaviours at key stages in the life cycle of plastic products, such as in design, manufacture, use, disposal and recovery, in order to reduce pollution and create the conditions to achieve a circular plastics economy.[31]

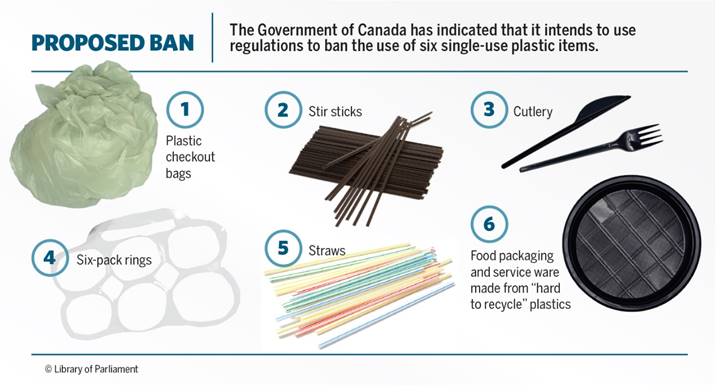

One of these regulations could be a ban on “harmful single-use plastics.” The Government of Canada proposes to ban six single-use plastic items, based on evidence that “they are found in the environment, are often not recycled, and have readily available alternatives.”[32] The six items are listed in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Items proposed to be banned under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999

Note: The proposed regulations include some exceptions related to flexible plastic straws.

Source: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament using information from Government of Canada, Discussion paper: A proposed integrated management approach to plastic products to prevent waste and pollution.

The Listing Process of the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999

The federal government plans to use CEPA to establish regulations affecting plastic manufactured items, including the proposed ban on certain single-use plastic items. CEPA is the main federal law for protecting human health and the environment. Its purpose is to prevent and manage risks posed by toxic and other harmful substances.[33] Within CEPA, a substance is toxic if

- it is entering or may

enter the environment in a quantity or concentration or under

conditions that:

- a) have or may have an immediate or long-term harmful effect on the environment or its biological diversity;

- b) constitute or may constitute a danger to the environment on which life depends; or

- c) constitute or may constitute a danger in Canada to human life or health.[34]

If the federal government determines—through a scientific assessment—that a substance is toxic, it may add the substance to Schedule 1 to CEPA, also known as the Toxic substances list. This list includes over 150 substances or groups of substances.[35] Schedule 1 lists substances that are easily associated with the everyday usage of the term “toxic” such as lead, mercury and its compounds, inorganic arsenic compounds, and dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT). Schedule 1 also lists substances that may not immediately be associated with the term but that meet the definition of “toxic” under CEPA, including greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide.

Once a substance is added to Schedule 1, the federal government is empowered to use various preventive or control measures to reduce or eliminate the release of the substance into the environment. These measures “may target any aspect of the substance’s life cycle, from the research and development stage through manufacture, use, storage, transport and ultimate disposal.”[36] CEPA provides for various preventive or control measures, such as regulations, pollution prevention plans, and environmental emergency plans.[37]

Table 3 presents the steps the Government of Canada must take in order to add “plastic manufactured items” to Schedule 1 to CEPA and develop regulations to ban certain single-use plastic items, and includes notes about actions taken to date.

Table 3: Regulating Plastics under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999

Step in regulatory process |

Timing and actions taken for plastic manufactured items and single-use plastics |

Identification of a substance as toxic under CEPA |

On 7 October 2020, the Government of Canada published the Science Assessment of Plastic Pollution. It determined that plastic pollution harms the environment and that the government should act to prevent plastic from entering the environment. |

Publication of proposal to add a substance to Schedule 1 followed by comment period |

On 10 October 2020, the Government of Canada published a proposal in Part I of the Canada Gazette to add “plastic manufactured items” to the Toxic substances list (also known as Schedule 1 to CEPA). |

Consideration of comments received |

The Government of Canada received several Notices of Objection to the proposal to add plastic manufactured items to Schedule 1, which criticized the science and called for further study. The Minister of Environment and Climate Change rejected these requests. The Government of Canada published a summary of the public comments received on the proposed addition of “plastic manufactured items” to Schedule 1. |

Addition of substance to Schedule 1 |

On 12 May 2021, the Government of Canada published the final order adding “plastic manufactured items” to Schedule 1 to CEPA in Part II of the Canada Gazette. |

Development of regulations using socio-economic analysis and cost‑benefit analysis |

Completed between May 2021 and December 2021. |

Publication of draft regulations followed by comment period |

On 25 December 2021, the Government of Canada published proposed regulations banning the manufacture, import or sale of single-use plastic checkout bags, single-use plastic cutlery, single-use plastic foodservice ware, single-use plastic ring carriers, single-use plastic stir sticks and single-use plastic straws. Exceptions are proposed for the manufacture, import and sale of single-use plastic flexible straws. Exceptions are proposed for the manufacture, import and sale of single-use plastic items for the purposes of export. In the case of export, certain records are required to be kept. Comments on the proposed regulations could be submitted to the Minister of Environment and Climate Change for 70 days after the publication—i.e., until 5 March 2022. A notice of objection requesting that a board of review be established could be filed for 60 days following publication—i.e., until 23 February 2022. |

Consideration of comments received from the public and stakeholders with the possibility to modify the proposed regulations based on the comments received |

Beginning after 5 March 2022. |

Publication of the final regulations in Part II of the Canada Gazette |

The Government of Canada may publish final regulations after consideration of the comments received and other factors. |

Coming into force of regulations |

The final regulations would come into force on the date they are registered or on a subsequent date identified in the regulations. |

Source: Prepared by the Committee using data obtained from Government of Canada, Science assessment of plastic pollution; Order Adding a Toxic Substance to Schedule 1 to the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999, 5 October 2020, in Canada Gazette, Part I, 10 October 2020; Government of Canada, “Notice of objection and request for board of review in relation to proposed order adding plastic manufactured items to Schedule 1 to the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 (CEPA),” Notices of objection; Government of Canada, Summary of public comments received on the proposed Order adding “plastic manufactured items” to Schedule 1 to the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999; Order Adding a Toxic Substance to Schedule 1 to the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999, SOR/2021-86, 23 April 2021, in Canada Gazette, Part II, 12 May 2021; Single-Use Plastics Prohibition Regulations, 25 December 2021, in Canada Gazette, Part I, 25 December 2021.

CEPA has already been used to ban plastic microbeads in personal care products. This process took approximately three years. Between August 2015 and June 2017, the government published proposed and final orders that added microbeads to Schedule 1, and then published proposed and final regulations that banned these microbeads. Regulations prohibiting the manufacture and import of all toiletries containing microbeads came into force on 1 July 2018.[38] Chelsea Rochman, Assistant Professor at the University of Toronto, told the Committee that the ban on microbeads has been effective and that fewer microbeads appear in the environment since the ban was issued.[39]

Impacts on Jobs and Industry of a Ban on Certain Single-Use Plastics

Various businesses and industry groups told the Committee that the government’s approach to regulating plastic manufactured items—particularly the proposed ban on some single-use plastics implemented through CEPA—would threaten jobs and deter investment in the plastics industry.[40]

In their testimony and submissions to the Committee, several witnesses cited an analysis from CIAC that estimated the economic impacts of a ban on all single-use plastics. As Elena Mantagaris, Vice-President of the Plastics Division at CIAC, explained: “bans in this country on single-use plastics writ large” could affect up to one-quarter of Canada’s existing plastic shipments.[41] As noted earlier, CIAC estimated that single-use plastics represent $5.5–$7.5 billion in annual sales, 13,000 to 20,000 direct jobs, and as many as 26,000 to 40,000 indirect jobs.[42] Sonya Savage, Minister of Energy of Alberta, said that a ban would be particularly damaging in her province, which is working to diversify its economy and attract new investment outside the oil and gas sector.[43] She cited analysis from CIAC estimating that a ban on all single-use plastics would put $100–$500 million in sales in Alberta at risk, “representing between 500 and 2,000 jobs.”[44]

In their testimony, representatives of CIAC said that a ban on some single-use plastics would disproportionately affect small- and medium-sized enterprises. Bob Masterson explained that many of these businesses produce a limited range of products, and that the government’s proposed ban might shut some enterprises out of the Canadian market.[45]

Witnesses told the Committee that the government’s proposed ban would damage the industry’s reputation and deter investment. According to Michael Burt, Vice-President and Global Director of Climate and Energy Policy at Dow:

This [ban] will significantly impact the perception of plastic in Canada and around the globe. This will negatively impact the investment climate in Canada for the petrochemical sector and is directly at odds with the government's initiative to restart the economy, in which the petrochemical sector plays a critical role.[46]

Minister Savage raised a similar point, saying the federal government’s approach would give the impression that Canada was hostile to the plastics industry:

We know that the global demand for petrochemicals is growing and companies are looking to invest. They have billions of dollars to invest. We believe this [ban] could drive investment away from Canada into other jurisdictions. Companies will look for jurisdictions that are the most competitive and that are not hostile to the business the company is trying to do.[47]

In their briefs to the Committee, plastics producers feared that designating plastic manufactured items as “toxic” could make it harder for their businesses to secure bank loans.[48]

One group argued that a ban on certain single-use plastics would not only threaten jobs and investment but could increase costs for some consumers: In its brief to the Committee, the Canada Coalition of Plastic Producers of the Foodservice Packaging Institute argued that “[b]ans will increase the cost of living and impact Canadians,” particularly “those out of work due to the pandemic and low-income groups.”[49] Commenting on the same issue, Philippe Cantin, Senior Director of Sustainability Innovation and Circular Economy at the Retail Council of Canada, said that it was difficult to anticipate how a ban on some single-use plastics would affect the cost of plastic items, and that the matter needed further study. However, he noted that materials generally become more expensive as their supply decreases. Mr. Cantin added that an implementation period would help small businesses adjust to any cost impacts of a ban.[50]

Some witnesses believed that the government was creating uncertainty by listing all “plastic manufactured items” on Schedule 1 to CEPA. They argued that this approach made it difficult for businesses and investors to anticipate the government’s intentions in the long term, for example, in relation to whether it would choose to expand the ban to other plastic items.[51] Minister Savage said there was a “great cloud of uncertainty” that was exacerbated by the “toxic” label,[52] while John Galt argued that uncertainty would deter investment and increase Canada’s reliance on imported goods.[53] In their briefs to the Committee, several businesses called on the Government of Canada to analyze the economic impacts of designating plastic manufactured items under CEPA and banning certain single-use plastic items.[54]

When the federal government published the order that added plastic manufactured items to Schedule 1 to CEPA, it noted that it had analyzed the potential impacts of its action. This included an analysis using a “small business lens” to examine the possible burden imposed on small businesses.[55] The government concluded that simply adding these items to Schedule 1 would have no impact on businesses, mainly because the listing does not create compliance costs. However, the government acknowledged that adding these items to Schedule 1 will allow ministers to develop risk management measures for plastic manufactured items, and that these measures “could result in incremental costs for stakeholders and the Government of Canada.”[56] The government explained that it would hold consultations and conduct a cost-benefit analysis as it developed these measures.

When the federal government published the proposed Single-Use Plastics Prohibition Regulations on 25 December 2021, it noted that the proposed regulations were expected to affect approximately 242,000 businesses that sell or offer the six categories of single-use plastic manufactured items affected by the proposed ban, 79 businesses that manufacture them and 43 businesses that import them.[57] The proposed regulations were expected to result in $1.9 billion in present value costs between 2023 and 2032. The costs, while representing a significant total, would be dispersed across Canadian consumers and represent a cost of approximately $5 per person per year. According to the analysis, the proposed regulations would result in benefits, mainly because of avoided costs related to terrestrial cleanup, worth $619 million over the same period. The net costs were therefore calculated to be $1.3 billion in present value costs between 2023 and 2032.[58]

Other witnesses described possible economic benefits from a ban on certain single-use plastics. Sophie Langlois‑Blouin, Vice-President of Operational Performance at RECYC-QUÉBEC, said that businesses could reduce their costs by using more sustainable products,[59] while Karen Wirsig, Program Manager, Plastics at Environmental Defence Canada, argued that “there are immensely more job opportunities available with getting away from single-use plastics, getting to the manufacturing of more durable containers, including durable plastic containers, and setting up reuse systems.”[60] She urged the government to phase out subsidies for the petrochemical industry, and to redirect those funds to help workers from the industry to transition into other roles.[61] Ashley Wallis, Plastics Campaigner at Oceana Canada, added that banning some single-use plastics might bring another kind of economic benefit by helping to reduce the costs associated with plastic pollution and even the costs of managing potential healthcare risks from that pollution.[62] Ashley Wallis also pointed to a study from the Ellen MacArthur Foundation that estimates “replacing 20% of single-use plastics globally with reusables would generate $10 billion in economic activity.”[63]

Significance of the “Toxic” Label

Schedule 1 to CEPA is also known as the “Toxic substances list.” The Committee heard diverging opinions about whether it was appropriate to add “plastic manufactured items” to such a list.

Several witnesses, including businesses throughout the plastics supply chain, argued that CEPA was the wrong tool for regulating plastic manufactured items. Above all, they argued that it was inaccurate to call plastics a “toxic” substance, noting that plastics are widely used in medical and food-safe applications.[64] Some of these witnesses supported a ban on certain single-use plastics, but objected to the designation of all plastic manufactured items as toxic.[65]

Several witnesses also contended that the Government of Canada took a flawed approach in adding the items to Schedule 1. In their briefs to the Committee, various businesses claimed that the government’s Science Assessment was incomplete and should not have made a recommendation about the management of plastics.[66] Minister Savage raised a further objection, saying that the federal government was intruding on provincial jurisdiction by using CEPA to regulate plastics.[67] The governments of Alberta, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec and Saskatchewan have objected to the use of CEPA for regulating plastics.[68]

Other witnesses disagreed, arguing that CEPA was the appropriate tool for regulating plastics. They emphasized that plastic meets the definition of a toxic substance as defined in CEPA.[69] Moreover, as Karen Wirsig told the Committee, “I think you won't be surprising, shocking or scaring any Canadian when you tell them that plastic is toxic to the environment.”[70] Whereas several witnesses worried that the government’s proposed ban would confuse consumers, others agreed with Ms. Wirsig, arguing that the public is aware that plastic can be toxic to the environment.[71]

Impacts on the Environment of a Ban on Certain Single-Use Plastics

Plastic mainly affects the environment in the form of pollution. When plastic is disposed of improperly and leaks into the environment, it becomes plastic pollution. As of 2016, roughly 1% of plastic used in Canada leaked into the environment as pollution.[72] Thanks in part to sound waste management, Canada is not a leading global source of plastic waste to marine environments.[73] Canada does, however, export waste overseas for processing, which could increase the potential for Canada’s plastic waste to be poorly managed and to be released into the environment. In 2020, Canada exported approximately 92,000 tonnes of plastic waste to other countries, primarily the United States.[74]

Plastic pollution can be released into the environment through littering, through environmental emergencies such as flooding events, through the wear and tear, abrasion or maintenance of certain items and through inadequate wastewater or stormwater management practices. Plastic pollution can be released into terrestrial or aquatic environments and move from one to another. Although plastic fragments and degrades in the environment, it persists for many years. Deborah Curran, Executive Director of the Environmental Law Centre at the University of Victoria, recommended that the Government of Canada take a long-term approach to managing plastics as “the persistence or legacy of plastics in our environment will now be with us for thousands of years.”[75]

Once it enters the environment, plastic can have negative effects on the natural world and on wildlife. For wildlife, plastics pose both physical threats (e.g., through entanglement, or gastrointestinal blockage by larger plastics) and chemical threats (through the internal accumulation of chemicals particularly associated with microplastics).[76] More than 600 marine species are harmed by marine litter and at least 15% of those are endangered.[77] For example, a study of 159 coral reef ecosystems in the Asia-Pacific region showed that contact with plastic waste increased the likelihood of disease among corals from 4% to 89%.[78] There are reports of hundreds of animal species being found entangled or having ingested pieces of plastic. Plastic can injure or even kill animals and leads to changes in the presence of different species at a particular location.[79]

Plastic waste—and plastic pollution—is often categorized into “macroplastics” and “microplastics.” Macroplastics are plastic items measuring more than 5 mm in diameter, while microplastics are plastic items measuring less than 5 mm in diameter. There is no lower limit to the size of microplastics, but the term “nanoplastic” is often used for particles smaller than a few micrometres.[80] Microplastics are often found during waterfront clean-ups, but they are difficult to identify once they have broken down. Identifiable sources of microplastics include rubber tires and textiles, which are durable plastics.[81] Single-use plastics can also be a source of microplastics in the environment. Microplastics are “ubiquitous in the environment, including in our Arctic and in seafood and drinking water extracted from the Great Lakes.”[82]

Animals at every level of the food web are exposed to microplastics.[83] The tiny particles can cause behavioural and reproductive changes in wildlife, and can be toxic to fish and invertebrates.[84] Microplastic concentrations are high enough in the Great Lakes to harm 5% of the species present.[85] Chelsea Rochman explained that there is some evidence that certain types of microplastics may “be more toxic than others” but she argued that “microplastics in general, as a mixture, [should] be kept out of the environment, regardless of material type.”[86] She acknowledged that there are many paths by which plastics can enter the environment, and that it is difficult to know the exact source of microplastic pollution.[87]

While all witnesses agreed that plastic does not belong in the environment, some wondered why the Government of Canada has focused on regulating plastic manufactured items instead of plastic waste or plastic pollution.[88] Some witnesses also pointed out that certain alternatives to single-use plastics can have larger environmental impacts than the single-use plastics they replace. For example, a life-cycle analysis of shopping bags by RECYC-QUÉBEC found that the single-use plastic bag had a lower environmental impact over its entire lifespan compared to reusable plastic or cotton bags.[89]

Both the production and lifecycle management of plastic have implications for greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, which in turn affect the environment. Because most plastics are made from fossil fuels, their production contributes to GHG emissions. The production of recycled plastic resins, on the other hand, creates 1.5 times fewer GHG emissions compared to virgin resins.[90]

At the same time, the use of plastic can reduce emissions compared to alternatives. John Galt stated that plastic requires less energy to produce or recycle because of its low melting point and that “[r]elative to the PET plastic used in a beverage container, paper composites have 1.6 times the carbon footprint, aluminum 1.7 times, and glass 4.4 times the carbon footprint. PET plastic does also not require deforestation or open-pit mining the way paper and aluminum do.”[91] As noted above, the light weight of plastics makes them useful for vehicles and aircraft parts, allowing these vehicles to use less fuel and produce fewer emissions.[92]

Impacts on Human Health of a Ban on Certain Single-Use Plastics

When used for their intended purposes, plastic items can play an important role in improving, or protecting, the health and safety of Canadians. Witnesses reminded the Committee of the critical role plastic had recently played, and continued to play, during the COVID‑19 pandemic, in part for its role in masks.[93] Plastic can also be found in many other medical items, such as heart stents and other medical devices. John Galt saw irony in adding plastic manufactured items to the Toxic substances list: “life-giving products and waste, both captured under the same designation.”[94] Ashley Wallis argued that using CEPA to ban unnecessary single-use plastic can “prioritize plastic for the places in our society where they might have real value, for example, in the medical space.”[95]

Human beings can also be exposed to plastics that have leaked into the environment. Exposures to macroplastics are not considered a concern for human health. In contrast, the effects of microplastics on human health are not well understood, but there is a consensus that more research is needed.[96]

Microplastics are found in drinking water as well as in the seafood human beings consume.[97] People breathe in microplastics, and it is possible that these plastic particles could damage human lungs.[98] Ashley Wallis highlighted a recent study that found microplastics in human umbilical cords and placentas, indicating that “unborn babies are exposed to plastic pollution in utero … We are exposed to plastic before we are born.”[99] However, the full impacts of these microplastics on human health, including the effect of gradually accumulating—or “bioaccumulating”—microplastics in the human body, are not currently known. To address these gaps and inform next steps, Chelsea Rochman suggested, the Government of Canada could convene a working group to research the impacts of microplastics on human and animal health.[100]

Recommendation 1

The Committee recommends that the Government of Canada amend its regulatory process to provide more certainty to groups that are affected by potential regulations in terms of economic costs and environmental impacts.

Recommendation 2

The Committee recommends that the Government of Canada convene a working group to study the impacts of microplastics on the environment and human health, including studying the effects of bioaccumulated microplastics.

Committee members expressed concerns about the impacts a single-use plastics ban could have on accessibility. On that subject, Philip Cantin gave the example of plastic straws, which can be an important accessibility tool for people with certain disabilities. He stated that “[e]xemptions [to the proposed ban] also need to be clearly defined, with considerations for accessibility, health, food safety, and security.”[101] Helen Ryan indicated that as the government designs regulations for single-use plastic items, ECCC will consider how to ensure that people with certain disabilities have the appropriate access to necessary tools.[102] As it develops regulations, she noted, the department will follow the Cabinet Directive on Regulation. This directive requires the department to “undertake an assessment of social and economic impacts of each regulatory proposal on diverse groups of Canadians” including people with a physical or mental disability.[103]

Recommendation 3

The Committee recommends that the Government of Canada set a clear intention to accommodate the needs of people with disabilities in any policy or regulation it adopts regarding single-use plastics.

Plastic packaging plays a role in preserving and extending the shelf life of food, which reduces food spoilage and food waste, and helps to ensure food safety.[104] William St‑Hilaire, Vice-President, Sales Business Development at Tilton, asserted that “[i]n the sectors we serve, eliminating plastics would lead to major food safety, security, sanitation and food waste issues.”[105] Sophie Langlois-Blouin believed that it would be possible to reduce both plastic packaging and food waste but “it must be done in an informed manner.”[106] Helen Ryan agreed it was “extremely important” that issues of food security be taken into account during the design of any potential regulation on plastics. She noted that the proposed ban on certain single-use plastic items did not apply to plastics used for food conservation in grocery stores but rather to food ware containers use for take-out purposes.[107]

Towards a Circular Economy for Plastics

“In summary, the era of take, make and toss, otherwise referred to as the linear economy, is over, and I think we can all agree with that.”[108]

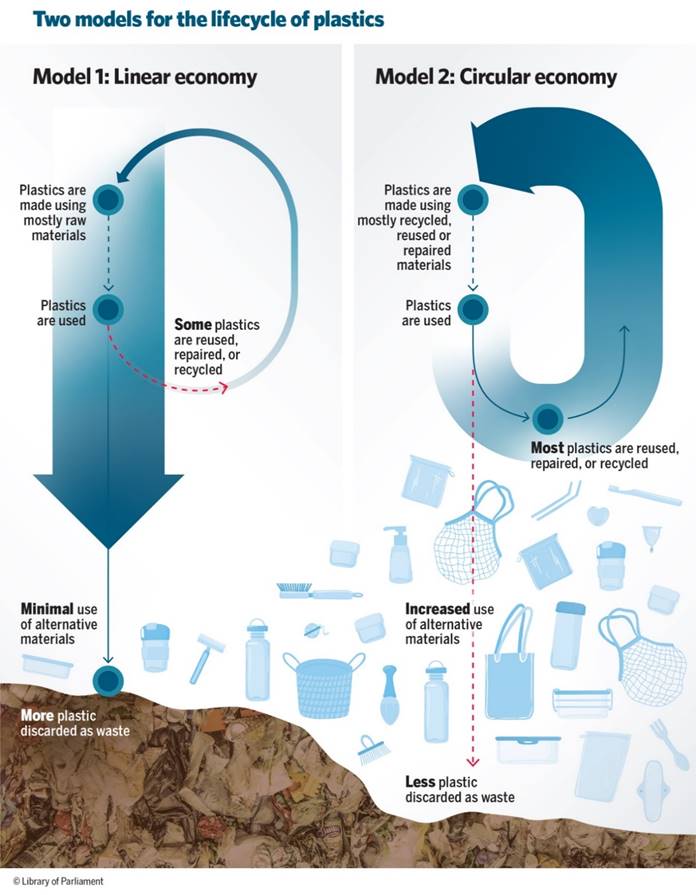

Canada’s plastics economy is mostly linear; that is, most plastic materials are not recovered or reused after being used. However, there is an alternative: witnesses were unanimous that Canada should work to establish a more “circular” plastics economy.[109]

A circular economy is an economic model that is intended to minimize resource consumption and waste. In contrast to a linear economic model in which resources are extracted, made into goods, and discarded, a circular economy emphasizes repair, reuse and/or recycling—maintaining the value of goods and services for as long as possible.[110]

Figure 2 shows how the principles of the circular economy could apply to plastics, compared to a linear economy for plastics.

Figure 2: Two models for the lifecycles of plastics

Source: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament

Building a Circular Economy

“As you know, there's no one-size-fits-all solution. Instead, we need a tool box of solutions that include those that help us build a circular economy.”[111]

Reduce

Many Canadians are familiar with the “Three Rs:” reduce, reuse, recycle. As Sophie Langlois‑Blouin noted, this means that the first step in waste management is to reduce the use of materials at their source.[112] Several witnesses emphasized that building a circular economy for plastics also means reducing the use of plastic, particularly single-use plastics.[113]

Some witnesses argued that a ban on certain single-use plastics would help reduce Canada’s use of plastic, as well as plastic pollution.[114] Ashley Wallis likened the problem of plastic pollution to an overflowing bathtub. She said that governments have so far focused on the wrong end of the supply chain, trying to mop up the overflow rather than “turning off the tap.” Bans, she argued, would help stop the “flow” of plastics and reduce their overall use.[115] Similarly, Chelsea Rochman supported a ban on certain single-use plastic items, saying that by reducing Canada’s reliance on unnecessary single-use plastics, the country can “bend our linear plastic economy toward a more circular one.”[116]

For other witnesses, particularly from the plastics industry, it was unnecessary to ban single-use plastics to reduce their use. Instead, these witnesses said that governments should focus on policies that improve waste management and allow plastic to recirculate in the economy, effectively eliminating one-time uses of plastic.[117] As William St‑Hilaire put it: “[t]he problem isn't single-use plastic, it's the single use of plastic that's the problem.”[118] These witnesses argued that the government should focus its attention on measures that improve the management of plastic waste, including through increased recycling.

Reuse and Recycle

The Committee heard significant discussion about the role that recycling will play in the circular economy. Witnesses generally agreed that the federal government could take additional steps to improve Canada’s recycling infrastructure and increase the rate at which plastics are reused and recycled.

The Committee heard from several witnesses who argued, as Michael Burt did, that “post-consumed plastic is a resource to be captured, not designated as a waste.”[119] These witnesses said that recycling would help keep plastic in the economy and out of the environment. However, some expressed concern that the government’s proposed ban on certain single-use plastic items would reduce the supply of post-consumer plastic, making it harder to scale-up recycling, and potentially deterring investments needed for a circular economy.[120] In the view of Tony Moucachen, President and Chief Executive Officer at Merlin Plastics, an approach focused on banning certain plastics “fails to recognize the value of post-consumer plastics to industry and society…suggest[ing] that the material is problematic, when in fact it is the absence of appropriate waste management systems that is the issue.”[121]

Other witnesses disputed this argument. They pointed out that the Government of Canada proposes to ban six single-use plastic items that are difficult or expensive to recycle, and that are unlikely to contribute to a circular economy.[122] Norman Lee summarized this challenge, noting that these plastic items “are often undetected and increasingly difficult to separate in municipal facilities. They contaminate our recycling and our compost, and are a major contributor to litter in our streets, parks and waterways.”[123] Karen Wirsig agreed with this point and mentioned that banning these items would help reduce the cost of recycling, which is mainly borne by municipalities.[124] Chelsea Rochman added that although in theory these six single-use plastic items can be recycled, in practice there is no market to do so.[125] In fact, some witnesses suggested that a single-use plastic ban could be expanded to include such items as wet wipes, plastic tampon applicators, single-use coffee cups and lids, cigarette butts, and all forms of polystyrene.[126]

It may be possible to improve the recyclability of some plastic products. The main technology used in the recycling sector—mechanical recycling—has several limitations. In addition to being expensive and energy intensive, it cannot remove contaminants from many types of plastic. However, there are other technologies that could make it easier to recycle various kinds of plastics and remove contaminants from used plastic.[127] One possibility is a group of technologies known collectively as “chemical recycling.” These technologies subject plastic to a combination of heat, pressure and chemicals, breaking the plastic down into its constituent chemicals. These chemicals can be repolymerized into new plastics or used as fuels or raw materials for other products.[128]

However, this technology is still developing and has yet to be deployed at scale. Accordingly, some witnesses—and several businesses that submitted briefs to the Committee—encouraged the federal government to invest in these technologies, to help them commercialize and scale up.[129]

Other witnesses were less optimistic about the advantages of chemical recycling. Norman Lee acknowledged that “chemical recycling and other advanced recycling technologies … hold some promise or potential” but said that “in practice they're still not there.”[130] He noted that pilot projects in advanced recycling showed that these technologies remain sensitive to contamination and moisture, and were not yet capable of producing new plastic polymers.[131] Some witnesses went further, arguing that the federal government could not rely on recycling alone to create a circular economy for plastics.[132] Ashley Wallis likewise rejected waste-to-energy and advanced recycling methods, calling them “waste disposal in disguise.”[133] She said the federal government should focus its investments in areas that would replace the use of virgin resins.

On increasing recycling capacity as a solution to plastic waste, Ashley Wallis argued that “we cannot recycle our way out of this crisis” and noted that “even in the best recycling scenario, by 2040, 45 million tonnes of plastic would be flowing into the global environment every year,” an increase of 7 million metric tonnes per year over today.[134]

Nonetheless, witnesses generally felt that the federal government could—and should—help strengthen Canada’s recycling sector. It can start by investing in the country’s recycling infrastructure, which Karen Wirsig described as “sorely lacking.”[135] William St‑Hilaire suggested that the federal government should invest in sorting centres, particularly in automated systems that can grade plastics according to their resin type.[136] Witnesses argued that these investments would not only help increase the recycling of plastics,[137] but would also encourage the plastics industry to manufacture more recyclable products.[138]

Some witnesses argued that the ban on single-use plastics should be paired with incentives and investments that support the development of reuse systems and noted that jobs in logistics, sanitation and technology for reuse can be created with relatively little investment. Karen Wirsig suggested that ECCC should host a round table for reuse companies and organizations to learn more about what infrastructure is needed to support reuse across the country.[139]

Recommendation 4

The Committee recommends that the Government of Canada host a roundtable for reuse companies and organizations, working with the Federation of Canadian Municipalities, to learn more about what infrastructure is needed to support reuse across Canada.

Recommendation 5

The Committee recommends that the Government of Canada invest in expanding the country’s recycling infrastructure and innovation, including by supporting the expansion of collection and sorting systems, and by investing in innovative technologies that can improve the rate at which plastics are recycled.

The federal government can also play an important role in harmonizing the different recycling systems that exist across Canada.[140] Municipalities are responsible for designing and implementing recycling programs, and these programs vary widely. Tony Moucachen explained that these differences are problematic for plastic producers, but also for consumers. He said: “There are many different approaches, especially in the blue box program… [This] confuses residents when they travel from one municipality to the next. The same is true with our green bin programs.”[141] However, municipalities are not the only players in the design of recycling programs. Sophie Langlois-Blouin noted that RECYC-QUEBEC coordinates with companies that market plastic, as well as with packers and recyclers[142]—and of course, provincial governments also play an important role in developing recycling and waste collection programs.[143] In their testimony, representatives of ECCC said that the Government of Canada was taking some steps to harmonize recycling standards in Canada. Helen Ryan mentioned that the government was developing proposals for these standards with the Standards Council of Canada and the Bureau de normalisation du Québec.[144]

Recommendation 6

The Committee recommends that the Government of Canada publish additional information on its work to harmonize recycling standards across Canada and seek additional opportunities to advance this harmonization in collaboration with provinces and territories, industry and communities.

Extended Producer Responsibility

One of the recurring challenges in expanding the reuse and recycling of plastics is a shortage of material.[145] Extended producer responsibility (EPR) schemes could help increase the supply of this material. EPR is a policy that makes producers, rather than consumers, responsible for managing a product at the end of its life.[146] It can expand the collection of post-consumer material and incentivize producers to incorporate environmental considerations into product design.[147]

British Columbia and Quebec currently have EPR systems in place for a range of goods, including plastic products. In Quebec, the system includes selective collection and a refundable deposit system.[148] In British Columbia, producers finance residential recycling programs, through curbside, multi-family, or depot collection programs.[149] The province has the highest recycling rates in Canada.[150]

Witnesses supported the expansion of EPR across Canada.[151] Usman Valiante, Technical Advisor at Canada Plastics Pact, explained that “when you make producers responsible for collecting and recycling materials, they then invest in systems to do so … [t]hat creates the supply of plastics that feed into the recycling systems that would go to companies … to produce the next cycle of products.”[152] Norman Lee added that EPR could attract investment in recycling processing since products would be collected in higher quantities.[153]

Some witnesses suggested that the federal government could establish a national EPR strategy to harmonize different EPR schemes across the country.[154] Jonathan Wilkinson, then Minister of Environment and Climate Change, informed the Committee that the federal government is working “with provinces and territories to put in place Extender Producer Responsibility Systems where they are responsible for collecting the plastics, and over time we will be ratcheting up the percentage that are going to have to be required to be recycled.”[155] The Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment approved a Canada-wide Action Plan for Extended Producer Responsibility in October 2009.[156]

Recommendation 7

The Committee recommends that the Government of Canada, in collaboration with provinces and territories:

- continue its work with the Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment (CCME) to develop guidelines for EPR programs across the country; and

- provide an update about the status of its EPR work with the CCME.

Recommendation 8

The Committee recommends that the Government of Canada work with the CCME to provide more regular progress reports on CCME work.

Improved Product Design

The circular economy depends partly on systems, like recycling and EPR. These systems, in turn, depend on effective product design. Witnesses explained that the federal government can introduce new product design standards that encourage the reuse and recycling of plastic products.

The federal government told the Committee about some of the work it is already doing in this area. Minister Wilkinson explained that the Government of Canada intends to use its authority under CEPA to require all plastic products to be made with a certain percentage of recycled material.[157] Many witnesses agreed that Canada should establish a recycled content requirement for plastic products, saying this requirement would incentivize more sustainable product design.[158] The Government of Canada’s long-term goal, outlined in the Ocean Plastics Charter, is to reach a 50% recycled content standard by 2030. It intends to develop these requirements in concert with various partners, including the Canada Plastics Pact and the Standards Council of Canada.[159]

Recommendation 9

The Committee recommends that the Government of Canada work with partners to accelerate the development and implementation of minimum recycled content standards.

Just as the federal government can set minimum standards for the content of plastic products, it can also set minimum standards for their marketing and labelling. Norman Lee suggested that the Government of Canada should establish “national labelling and advertising standards” for plastic products, “to reduce consumer and resident confusion.”[160] Other witnesses agreed.[161] Sophie Langlois-Blouin suggested that the Competition Bureau of Canada could issue labelling directions that would make it easier for consumers and businesses to recognize and sort plastic products.[162]

The Government of Canada could go further and incentivize the manufacture and purchase of more sustainable packaging. Witnesses mentioned two—complementary—approaches that the government could take. First, jurisdictions could levy “eco-fees” on packaging. An eco-fee is a surcharge that is added to a good depending on its carbon footprint. The proceeds from the fee finance the recovery and recycling of the good at the end of its life cycle. Tony Moucachen and Maja Vodanovic, Mayor of the Borough of Lachine in Montreal, told the Committee that jurisdictions should charge an eco-fee—and the federal government should require the value of the fee to be posted on the product label. They argued that these fees would help change consumer behaviour and incentivize better product design.[163] In the second approach, the federal government could establish certification programs for different materials to help promote products with a lower carbon footprint and to simplify recycling and reuse.[164] Witnesses pointed out that these certification and labelling standards would only become more important as new types of materials enter the market.[165]

Alternative Materials

Manufacturers are exploring alternatives to conventional plastics. “Bioplastics” is a term commonly used to refer to plastic alternatives that mimic the useful qualities of fossil fuel-based plastics but are made from renewable sources, including waste or by-products from other industries.[166] Bioplastics can be broadly divided into natural polymers[167] and materials, such as cellulose, and biomass-based polymers, such as polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA).

Some bioplastics are made with biomass but are recyclable in the same waste streams as fossil fuel-derived plastic.[168] Other bioplastics are compostable. Bioplastics are mainly produced in China, and in the United States and Europe to a certain extent. Dr. Misra suggested that this was an area where Canada could develop its capacities and become a world leader. She noted that bioplastics were unlikely to be produced in sufficient quantities to replace conventional plastics for many years.[169]

Despite their name, bioplastics are not necessarily biodegradable. Marc Olivier, Research Professor and the Université de Sherbrooke, acknowledged that “[t]he word bioplastics causes a lot of confusion. Because the word starts with the prefix ‘bio,’ people believe that bioplastics are biodegradable. That is not the case at all.”[170] Furthermore, certain “compostable” bioplastics are only truly compostable in industrial facilities and not in backyard compost bins.[171] Even at industrial facilities, bioplastics can present new challenges to waste systems. These materials can contaminate the waste stream of recyclable plastics or compostable materials, making them impossible to reuse.[172]

Recommendation 10

The Committee recommends that the Government of Canada take steps to help Canadians distinguish between plastics and plastic alternatives based on how recyclable, compostable or biodegradable they are by, for example, establishing national labelling standards.

Conclusion

Everyone can agree that plastic does not belong in the environment. The challenge is to identify the right tools that stop plastic from becoming plastic pollution. Witnesses who testified during this study were divided about whether a ban on harmful single-use plastics is one of these tools. The Committee heard from various witnesses, particularly from the plastics industry, who argued strongly against the Government of Canada’s proposal to regulate plastic manufactured items using CEPA. They contended that the government’s approach, including a possible ban on some single-use plastics, would harm the plastics industry and make it harder to transition to a circular economy. Other witnesses felt equally strongly that the federal government should ban certain single-use plastics. They agreed with the government’s argument that certain single-use plastics are simply unnecessary: that they harm the environment, are too difficult to recycle, and can be replaced with other products.

The ways that we make, use, and manage plastic are changing. Witnesses emphasized that Canada—and the world—must move toward a circular economy for plastics that minimizes the use of raw materials and the creation of waste. To build this circular economy, the Committee has outlined steps that the Government of Canada can take to strengthen the country’s recycling sector, harmonize waste management programs, encourage better product design, and foster innovation. Taken together, these steps can help to make the one-time use of plastic products a thing of the past.

[1] The study on single-use plastics began and witnesses appeared before the House of Commons Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development (the Committee) during the 43rd Parliament. The members of the Committee for the 44th Parliament wish to thank the members who served on the Committee during the 43rd Parliament.

[2] Anne Trafton, World Economic Forum, These MIT chemists are making tough plastics easier to recycle, 29 July 2020.

[3] Ibid.

[4] American Chemistry Council, Plastic Packaging Resins.

[5] Government of Canada, Moving Canada toward zero plastic waste: Closed consultation.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC), Economic Study of the Canadian Plastic Industry, Markets and Waste: Summary Report to Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2019.

[8] House of Commons, Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development (ENVI), Evidence, 21 April 2021, 1540 (Bob Masterson, President and Chief Executive Officer, Chemistry Industry Association of Canada).

[9] ENVI, Evidence, 12 April 2021, 1715 (Elena Mantagaris, Vice-President, Plastics Division, Chemistry Industry Association of Canada).

[10] New technologies, such as bioplastics, are being developed and their role is explored later in this report.

[11] ECCC, Economic Study of the Canadian Plastic Industry, Markets and Waste: Summary Report to Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2019.

[12] ENVI, Evidence, 3 April 2019, 1610 (Carol Hochu, President and Chief Executive Officer, Canadian Plastics Industry Association).

[13] ENVI, Evidence, 12 April 2021, 1635 (John Galt, President and Chief Executive Officer, Husky Injection Molding Systems Ltd.); see also Norbert Sparrow, “Global medical disposables market to hit $273 billion in 2020,” Plastics Today, 31 August 2016.

[15] ENVI, Evidence, 6 May 2019, 1600 (Philippe Cantin, Senior Director, Circular Economy and Sustainable Innovation, Montreal Office, Retail Council of Canada).

[16] Emily J. North and Rolf U. Halden, “Plastics and Environmental Health: The Road Ahead,” in Reviews on Environmental Health, Vol. 28, No. 1, January 2013.

[17] ENVI, Evidence, 21 April 2021, 1540 (Manjusri Misra, Professor and Tier 1 Canada Research Chair in Sustainable Biocomposites, University of Guelph).

[18] ENVI, Evidence, 5 May 2021, 1550 (Helen Ryan, Associate Assistant Deputy Minister, Environmental Protection Branch, Department of Environment).

[20] Ibid.

[22] ENVI, Evidence, 5 May 2021, 1630 (Dany Drouin, Director General, Plastics and Waste Management Directorate, Department of Environment).

[24] ENVI, Evidence, 28 April 2021, 1535 (Jim Goetz, President, Canadian Beverage Association); ENVI, Evidence 28 April 2021, 1540 (Jim Goetz); and ENVI, Evidence, 5 May 2021, 1635 (Helen Ryan).

[26] ENVI, Evidence, 28 April 2021, 1550 (Norman Lee, Director, Waste Management, Regional Municipality of Peel).

[27] Government of Canada, A stronger and more resilient Canada: Speech from the Throne to open the Second Session of the Forty-Third Parliament of Canada.

[28] Government of Canada, Science assessment of plastic pollution.

[29] Government of Canada, A proposed integrated management approach to plastic products to prevent waste and pollution.

[30] Government of Canada, “Choosing the best instruments,” A proposed integrated management approach to plastic products to prevent waste and pollution.

[32] Government of Canada, Canada one-step closer to zero plastic waste by 2030, News release, 7 October 2020.

[33] Government of Canada, “2. Environmental management in Canada,” Guide to understanding the Canadian Environmental Protection Act: chapter 2.

[34] Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 (CEPA), S.C. 1999, c. 33, s. 64.

[35] Government of Canada, Toxic substances list: schedule 1.

[36] Government of Canada, “5. Existing substances,” Guide to understanding the Canadian Environmental Protection Act: chapter 5.

[37] Current, proposed and repealed regulations, pollution prevention plans and environmental emergency plans are available online on the CEPA registry.

[38] Government of Canada, Microbeads.

[39] ENVI, Evidence, 12 April 2021, 1615 (Chelsea M. Rochman, Assistant Professor, University of Toronto).

[40] CKF Inc., “Re: Study on Single-Use Plastics,” Brief submitted to ENVI, 31 March 2021; CCC Plastics, “Re: Study on Single-Use Plastics,” Brief submitted to ENVI, 5 April 2021; Hymopack Ltd., “Re: Study on Single-Use Plastics,” Brief submitted to ENVI, 5 April 2021; Peel Plastic Products Inc., “Re: Study on Single-Use Plastics,” Brief submitted to ENVI, 5 April 2021; INEOS Styrolution, “Re: Study on Single-Use Plastics,” Brief submitted to ENVI, 6 April 2021; Pack All Manufacturing Inc., “Re: Study on Single-Use Plastics,” Brief submitted to ENVI, 6 April 2021; Pactiv Evergreen, “Re: Study on Single-Use Plastics,” Brief submitted to ENVI, 6 April 2021; Winpak, “Re: Study on Single-Use Plastics,” Brief submitted to ENVI, 6 April 2021; and Dart Container Corporation, “Re: Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development’s study on the ban of single‐use plastics,” Brief submitted to ENVI, 19 April 2021.

[42] Dart Container Corporation, “Re: Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development’s study on the ban of single‐use plastics,” Brief submitted to ENVI, 19 April 2021.

[46] ENVI, Evidence, 21 April 2021, 1550 (Michael Burt, Vice-President and Global Director, Climate and Energy Policy, Dow).

[48] CKF Inc., “Re: Study on Single-Use Plastics,” Brief submitted to ENVI, 31 March 2021; CCC Plastics, “Re: Study on Single-Use Plastics,” Brief submitted to ENVI, 5 April 2021; Hymopack Ltd., “Re: Study on Single-Use Plastics,” Brief submitted to ENVI, 5 April 2021; Peel Plastic Products Inc., “Re: Study on Single-Use Plastics,” Brief submitted to ENVI, 5 April 2021; INEOS Styrolution, “Re: Study on Single-Use Plastics,” Brief submitted to ENVI, 6 April 2021; Pack All Manufacturing Inc., “Re: Study on Single-Use Plastics,” Brief submitted to ENVI, 6 April 2021; Pactiv Evergreen, “Re: Study on Single-Use Plastics,” Brief submitted to ENVI, 6 April 2021; Winpak, “Re: Study on Single-Use Plastics,” Brief submitted to ENVI, 6 April 2021.

[49] Canada Coalition of Plastic Producers of the Foodservice Packaging Institute, “Brief Submitted to The Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development Study on the Ban of Single-Use Plastics,” Brief submitted to ENVI, 1 April 2021.

50 ENVI, Evidence, 26 April 2021, 1710 (Philippe Cantin).

[51] ENVI, Evidence, 12 April 2021, 1605 (Bob Masterson); ENVI, Evidence, 12 April 2021, 1635 (John Galt); and ENVI, Evidence, 21 April 2021, 1605 (Michael Burt).

[54] CKF Inc., “Re: Study on Single-Use Plastics,” Brief submitted to ENVI, 31 March 2021; CCC Plastics, “Re: Study on Single-Use Plastics,” Brief submitted to ENVI, 5 April 2021; Hymopack Ltd., “Re: Study on Single-Use Plastics,” Brief submitted to ENVI, 5 April 2021; Peel Plastic Products Inc., “Re: Study on Single-Use Plastics,” Brief submitted to ENVI, 5 April 2021; INEOS Styrolution, “Re: Study on Single-Use Plastics,” Brief submitted to ENVI, 6 April 2021; Pack All Manufacturing Inc., “Re: Study on Single-Use Plastics,” Brief submitted to ENVI, 6 April 2021; Pactiv Evergreen, “Re: Study on Single-Use Plastics,” Brief submitted to ENVI, 6 April 2021; Winpak, “Re: Study on Single-Use Plastics,” Brief submitted to ENVI, 6 April 2021; and Dart Container Corporation, “Re: Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development’s study on the ban of single‐use plastics,” Brief submitted to ENVI, 19 April 2021.

[55] The principles that the Government of Canada follows when analyzing the potential impact of regulations on business are outlined in the Policy on Limiting Regulatory Burden on Business. See: Government of Canada, Policy on Limiting Regulatory Burden on Business.

[56] Order Adding a Toxic Substance to Schedule 1 to the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999, SOR/2021-86, 23 April 2021, in Canada Gazette, Part II, 12 May 2021.

[57] Single-Use Plastics Prohibition Regulations, 25 December 2021, in Canada Gazette, Part I, 25 December 2021.

[58] Ibid.

[59] ENVI, Evidence, 12 April 2021, 1555 (Sophie Langlois-Blouin, Vice-President, Operational Performance, RECYC‑QUÉBEC).

[60] ENVI, Evidence, 28 April 2021, 1705 (Karen Wirsig, Program Manager, Plastics, Environmental Defence Canada).

[63] Ibid.

[64] CKF Inc., “Re: Study on Single-Use Plastics,” Brief submitted to ENVI, 31 March 2021; CCC Plastics, “Re: Study on Single-Use Plastics,” Brief submitted to ENVI, 5 April 2021; Hymopack Ltd., “Re: Study on Single-Use Plastics,” Brief submitted to ENVI, 5 April 2021; Peel Plastic Products Inc., “Re: Study on Single-Use Plastics,” Brief submitted to ENVI, 5 April 2021; INEOS Styrolution, “Re: Study on Single-Use Plastics,” Brief submitted to ENVI, 6 April 2021; Pack All Manufacturing Inc., “Re: Study on Single-Use Plastics,” Brief submitted to ENVI, 6 April 2021; Pactiv Evergreen, “Re: Study on Single-Use Plastics,” Brief submitted to ENVI, 6 April 2021; Winpak, “Re: Study on Single-Use Plastics,” Brief submitted to ENVI, 6 April 2021; and Dart Container Corporation, “Re: Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development’s study on the ban of single‐use plastics,” Brief submitted to ENVI, 19 April 2021.

[65] ENVI, Evidence, 26 April 2021, 1605 (Philippe Cantin); and ENVI, Evidence, 26 April 2021, 1705 (Marc Olivier, Research Professor, Université de Sherbrooke).

[66] The Vinyl Institute of Canada, “Re: Submission to the Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development—Study on Ban of Single Use Plastics and Designating Plastics Under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act,” Brief submitted to ENVI, 25 March 2021; Norwich Plastics, “Re: Submission to the Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development—Study on Ban of Single Use Plastics and Designating Plastics Under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act,” Brief submitted to ENVI, 26 March 2021; Shintech, “Re: Submission to the Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development—Study on Ban of Single Use Plastics and Designating Plastics Under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act,” Brief submitted to ENVI, 8 April 2021; and PVC Pipe Association, “Re: Submission to the Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development—Study on Ban of Single Use Plastics and Designating Plastics Under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act,” Brief submitted to ENVI, 29 March 2021.

[68] ENVI, Evidence, 28 April 2021, 1710 (Sonya Savage); and ENVI, Evidence, 12 May 2021, 1745 (Helen Ryan).

[69] ENVI, Evidence, 12 April 2021, 1650 (Chelsea Rochman); ENVI, Evidence, 21 April 2021, 1610 (Deborah Curran, Executive Director, Environmental Law Centre, University of Victoria); and ENVI, Evidence, 28 April 2021, 1630 (Ashley Wallis).

[71] ENVI, Evidence, 21 April 2021, 1550 (Michael Burt); ENVI, Evidence, 26 April 2021, 1545 (Philippe Cantin); ENVI, Evidence, 26 April 2021, 1550 (Tony Moucachen); ENVI, Evidence, 21 April 2021, 1650 (Deborah Curren); and ENVI, Evidence, 28 April 2021, 1630 (Ashley Wallis).

[72] ECCC, Economic Study of the Canadian Plastic Industry, Markets and Waste: Summary Report to Environment and Climate Change Canada, 2019.

[73] J.R. Jambeck et al., “Plastic waste inputs from land into ocean,” Science, Vol. 347, Issue 6223, 2015.

[74] Statistics Canada, “Table 980-0039: Domestic exports—Plastics and articles thereof, 391590 Plastics waste and scrap, nes,” Canadian International Merchandise Trade Database, accessed 29 May 2021.

[76] United States Environmental Protection Agency, Toxicological Threats of Plastic.

[77] Government of Canada, Moving Canada toward zero plastic waste: Closed consultation.

[78] J.B. Lamb et al., “Plastic waste associated with disease on coral reefs,” Science, Vol. 359, 2018.

[80] Nature Nanotechnology, Nanoplastic should be better understood, Editorial, 3 April 2019.

[84] ENVI, Evidence, 28 April 2021, 1700 (Ashley Wallis); and ENVI, Evidence, 12 April 2021, 1530 (Chelsea Rochman).

[88] ENVI, Evidence, 12 April 2021, 1610 (Chelsea Rochman); ENVI, Evidence, 21 April 2021, 1550 (Michael Burt); ENVI, Evidence, 21 April 2021, 1625 (Deborah Curran); ENVI, Evidence, 28 April 2021, 1540 (Karen Wirsig); and ENVI, Evidence, 12 May 2021, 1720 (Jonathan Wilkinson, Minister of Environment and Climate Change, Department of Environment).

[93] ENVI, Evidence, 12 April 2021, 1635 (John Galt); and ENVI, Evidence, 26 April 2021, 1540 (Tony Moucachen).

[96] A. Dick Vethaak and Juliette Legler, “Microplastics and human health,” Science, Vol. 371, No. 6530, 12 February 2021; Order Adding a Toxic Substance to Schedule 1 to the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999, 5 October 2020, in Canada Gazette, Part I, 10 October 2020; and World Health Organization, WHO calls for more research into microplastics and a crackdown on plastic pollution, News release, 22 August 2019.

Since the Committee heard from its last witnesses in May 2021, more research has been published on the impacts of microplastics on human health. This research indicates that microplastics are likely to have negative impacts on human health. For example, a review accepted for publication in November 2021 found that cell death, allergic response and damage to cell membranes were detectable at the levels to which people are exposed to microplastics through contaminated drinking water, seafood and table salt. See: E. Danopoulos, et al., “A rapid review and meta-regression analyses of the toxicological impacts of microplastic exposure in human cells,” Journal of Hazardous Materials, Vol. 427, 2022.

[103] Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat, “5.2.3 Gender-based analysis plus (GBA+),” Cabinet Directive on Regulation.

[104] ENVI, Evidence, 12 April 2021, 1555 (Sophie Langlois-Blouin); and ENVI, Evidence, 21 April 2021, 1550 (Michael Burt); and ENVI, Evidence, 26 April 2021, 1640 (Philippe Cantin).

[105] ENVI, Evidence, 21 April 2021, 1555 (William St-Hilaire, Vice-President, Sales Business Development, Tilton).

[107] ENVI, Evidence, 5 May 2021, 1620 (Helen Ryan); and ENVI, Evidence, 5 May 2021, 1620 (Helen Ryan).

[109] ENVI, Evidence, 12 April 2021; 1530 (Chelsea Rochman); ENVI, Evidence, 12 April 2021; 1540 (Bob Masterson); ENVI, Evidence, 12 April, 1545 (John Galt); ENVI, Evidence, 12 April 2021, 1550 (George Roter); ENVI, Evidence, 12 April 2021, 1620 (Sophie Langlois-Blouin); ENVI, Evidence, 21 April 2021, 1535 (Deborah Curren); ENVI, Evidence, 21 April 2021, 1545 (Laurence Boudreault, General Manager, Bosk Bioproduits Inc.); ENVI, Evidence, 21 April 2021, 1550 (Michael Burt); ENVI, Evidence, 21 April 2021, 1555 (William St‑Hilaire); ENVI, Evidence, 21 April 2021, 1650 (Manjusri Misra); ENVI, Evidence, 26 April 2021, 1530 (Maja Vodanovic); ENVI, Evidence, 26 April 2021, 1555 (Philippe Cantin); ENVI, Evidence, 26 April 2021, 1700 (Tony Moucachen); ENVI, Evidence, 28 April 2021, 1535 (Jim Goetz); ENVI, Evidence, 28 April 2021, 1545 (Ashley Wallis); ENVI, Evidence, 28 April 2021, 1605 (Norman Lee); ENVI, Evidence, 28 April 2021, 1610 (Karen Wirsig); ENVI, Evidence, 28 April 2021, 1620 (Sonya Savage); ENVI, Evidence, 5 May 2021, 1550 (Helen Ryan).

[110] Government of Canada, Circular Economy; and Stephanie Cairns et al., Getting to a Circular Economy: A Primer for Canadian Policymakers, Policy Brief, Smart Prosperity Institute, January 2018.

[113] ENVI, Evidence, 12 April 2021, 1530 (Chelsea Rochman); ENVI, Evidence, 12 April 2021, 1715 (Sophie Langlois‑Blouin); ENVI, Evidence, 21 April 2021, 1540 (Deborah Curren); ENVI, Evidence, 28 April 2021, 1545 (Ashley Wallis).

[114] ENVI, Evidence, 12 April 2021, 1530 (Chelsea Rochman); and ENVI, Evidence, 28 April 2021, 1625 (Ashley Wallis).

[117] ENVI, Evidence, 12 April 2021, 1715 (Elena Mantegaris); and ENVI, Evidence, 12 April 2021, 1545 (John Galt).

[119] ENVI, Evidence, 21 April 2021, 1550 (Michael Burt). See also: ENVI, Evidence, 12 April 2021, 1545 (John Galt); ENVI, Evidence, 26 April 2021, 1700 (Maja Vodanovic); ENVI, Evidence, 28 April 2021, 1705 (Norman Lee)

[120] ENVI, Evidence, 12 April 2021; 1540 (Bob Masterson); ENVI, Evidence, 12 April 2021, 1630 (John Galt); and ENVI, Evidence, 26 April 2021, 1540 (Tony Moucachen).

[122] ENVI, Evidence, 26 April 2021, 1640 (Maja Vodanovic); and ENVI, Evidence, 12 May 2021, 1720 (Jonathan Wilkinson).

[126] ENVI, Evidence, 12 April 2021, 1620 (Chelsea Rochman); and ENVI, Evidence, 28 April 2021, 1750 (Ashley Wallis).

[128] Andrew N. Rollinson and Jumoke Oladejo, Chemical Recycling: Status, Sustainability and Environmental Impacts, Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives, 2020; and Allan Gerlat, “The promise of chemical recycling,” Recycling Today, 8 October 2018.

[129] ENVI, Evidence, 12 April 2021, 1725 (Elena Mantagaris); ENVI, Evidence, 21 April 2021, 1710 (Michael Burt); The Vinyl Institute of Canada, “Re: Submission to the Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development—Study on Ban of Single Use Plastics and Designating Plastics Under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act,” Brief submitted to ENVI, 25 March 2021; Norwich Plastics, “Re: Submission to the Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development—Study on Ban of Single Use Plastics and Designating Plastics Under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act,” Brief submitted to ENVI, 26 March 2021; Shintech, “Re: Submission to the Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development—Study on Ban of Single Use Plastics and Designating Plastics Under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act,” Brief submitted to ENVI, 8 April 2021; and PVC Pipe Association, “Re: Submission to the Standing Committee on Environment and Sustainable Development—Study on Ban of Single Use Plastics and Designating Plastics Under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act,” Brief submitted to ENVI, 29 March 2021.

[131] Ibid.

[132] ENVI, Evidence, 28 April 2021, 1540 (Karen Wirsig); and ENVI, Evidence, 28 April 2021, 1545 (Ashley Wallis).

[134] Ibid.

[138] ENVI, Evidence, 26 April 2021, 1540 (Tony Moucachen); ENVI, Evidence, 28 April 2021, 1540 (Karen Wirsig); and ENVI, Evidence, 12 April 2021, 1620 (Sophie Langlois‑Blouin).

[139] ENVI, Evidence, 28 April 2021, 1545 (Ashley Wallis); and ENVI, Evidence, 28 April 2021, 1540 (Karen Wirsig).

[145] ENVI, Evidence, 12 April 2021, 1710 (Bob Masterson); and ENVI, Evidence, 21 April 2021, 1700 (William St‑Hilaire).

[146] Government of Canada, Overview of extended producer responsibility in Canada.

[147] Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment (CCME), Canada-Wide Action Plan for Extended Producer Responsibility, October 2009.

[149] Recycle BC, Recycle BC FAQS.

[151] ENVI, Evidence, 26 April 2021, 1620 (Maja Vodanovic); ENVI, Evidence, 28 April 2021, 1535 (Jim Goetz); ENVI, Evidence, 28 April 2021, 1550 (Norman Lee); and ENVI, Evidence, 28 April 2021, 1620 (Sonia Savage).

[154] ENVI, Evidence, 26 April 2021, 1620 (Maja Vodanovic); ENVI, Evidence, 28 April 2021, 1655 (Jim Goetz); and ENVI, Evidence, 28 April 2021, 1550 (Norman Lee).

[156] CCME, Canada-Wide Action Plan for Extended Producer Responsibility, October 2009.

[157] ENVI, Evidence, 12 May 2021, 1710 (Jonathan Wilkinson).