HESA Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

A DIABETES STRATEGY FOR CANADA

Introduction

Diabetes is the cause of death for over 7,000 Canadians per year.[1] According to the International Diabetes Federation, Canada is “among the worst OECD [Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development] countries for diabetes prevalence.”[2]

Diabetes affects children and adults. It affects families, communities, and nations. Indigenous peoples in Canada are disproportionately affected by diabetes. Other population groups in Canada, such as people of South Asian, East Asian, and African descent, are also disproportionately affected by diabetes.

Individuals with diabetes cannot properly regulate the amount of glucose in their blood, which can lead to a host of related physical health issues and, in many cases, mental health issues such as depression and anxiety. The financial burden of managing diabetes is an added stress, with many costs not covered by provincial and territorial health insurance programs.

On 21 March 2017, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Health (the Committee) agreed “to study anti-diabetes strategies in Canada and in other jurisdictions.”[3] Over the course of six meetings held in the spring and fall of 2018, the Committee heard from 32 witnesses and received 12 briefs. Witnesses included individuals living with diabetes, advocacy organizations and health care professionals. Individuals shared very personal accounts of their struggles to manage their diabetes with often limited resources, and the Committee is grateful for their candor and openness. The Committee appreciates the time taken by witnesses who appeared before the Committee as well as those who provided input on this study by providing a written brief.

Background

What is Diabetes?

According to the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC), diabetes mellitus is a chronic disease that occurs when the body is either unable to sufficiently produce or properly use insulin.[4] Insulin is a hormone secreted by beta cells in the pancreas that enables the cells of the body to absorb sugar from the bloodstream and use it as an energy source. If left uncontrolled, diabetes results in consistently high blood sugar levels, a condition known as hyperglycemia. Over time, hyperglycemia can damage blood vessels, nerves and organs such as the kidneys, eyes and heart, resulting in serious complications and, ultimately, death. There are three main types of diabetes:[5]

- Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune disease in which an individual’s immune system attacks and destroys the insulin-producing cells of the pancreas, thereby leaving the individual dependent on an external source of insulin for life. Type 1 diabetes typically arises in individuals under 40 years of age, most often in children and youth. Approximately 10% of people with diabetes have type 1 diabetes.

- Type 2 diabetes is a metabolic disorder that occurs when the pancreas does not produce enough insulin and the body does not properly use the insulin it makes. While the onset of type 2 diabetes typically occurs in adults over 40 years of age, it can occur in younger individuals and is seen even in children and youth. Approximately, 90% of people with diabetes have type 2 diabetes.

- Gestational Diabetes occurs when hyperglycemia develops during pregnancy. Although elevated glycemic levels typically disappear following delivery, women diagnosed with gestational diabetes are at an increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes within 5 to 10 years.

An individual who has a higher-than-normal blood glucose level that is not high enough to result in a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes is referred to as prediabetic. Approximately 5.6 million people in Canada have prediabetes.[6]

The Committee heard that there are three million Canadians who have been diagnosed as having diabetes, and this number will increase as the population grows and ages.[7] Due to several factors, including a lack of awareness, many individuals who have type 2 diabetes have not yet been diagnosed. Diabetes Canada estimates that approximately 1.5 million people in Canada do not know they have type 2 diabetes.[8]

Who is at Risk?

Type 1 Diabetes

“Canada has one of the highest incidence rates of type 1 diabetes worldwide… [i]t is increasing in prevalence for reasons we don't understand.”

Dr. Bruce Verchere, professor, Department of Surgery, Pathologoy and Laboratory Medicine, University of British Columbia

It is not known what causes type 1 diabetes, which used to be referred to as juvenile diabetes. There is a genetic component, and individuals with other autoimmune conditions may be more susceptible to developing type 1 diabetes. Dave Prowten, President and Chief Executive Officer of the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation Canada (JDRF) explained that “we're starting to understand the genesis of this disease.”[9] While type 1 diabetes primarily has its onset in childhood, 20% of individuals with type 1 diabetes are diagnosed as adults.[10] The Committee heard from diabetes researcher Dr. Bruce Verchere, professor, Departments of Surgery, Pathology and Laboratory Medicine at the University of British Columbia, that “Canada has one of the highest incidence rates of type 1 diabetes worldwide,”[11] and that “[i]t is increasing in prevalence for reasons we don't understand.”[12]

Type 2 Diabetes

While obesity has long been understood as a key contributing factor to developing type 2 diabetes, the Committee heard that “[t]ype 2 diabetes is caused by a complex array of factors, including genetics, lifestyle, and such environmental factors as poverty, food insecurity, and a disease-promoting food and physical environment.”[13] While some of these determinants of health cannot be modified, social and environmental conditions can be changed.[14] Low-income Canadians are four times more likely to have type 2 diabetes than other Canadians.

Seniors and individuals of South Asian, East Asian and African ethnic backgrounds are also at greater risk of developing type 2 diabetes than other population groups in Canada.[15] Deljit Bains, the leader of the South Asian Health Institute at Fraser Health, explained that the diabetes rate is three times higher in the South Asian community in the Fraser Health region, and that diet is a key contributing factor.[16]

While social determinants of health are important risk factors for developing type 2 diabetes in the non-pediatric population, Dr. Mélanie Henderson, Pediatric Endocrinologist and associate professor, Centre hospitalier universitaire Sainte-Justine told the Committee that “[o]besity is the number one risk factor for type 2 diabetes in children.”[17]

Indigenous Peoples

“The complex interaction of access to appropriate and equitable care related to socioeconomic status, geography, infrastructures, language and cultural barriers, jurisdictional issues demonstrate the multifactorial causes of types 2 diabetes in Indigenous population[s].”

Canadian Indigenous Nurses Association

Valerie Gideon, Senior Assistant Deputy Minister of the First Nations and Inuit Health Branch at Indigenous Services Canada told the Committee that “diabetes rates are three to four times higher among First Nations than among the general Canadian population and all Indigenous [p]eoples are at increased risk of developing diabetes.”[18] In addition, Indigenous individuals are diagnosed with type 2 diabetes at a younger age than other individuals.[19] Individuals in a First Nation community who are in their twenties have an 80% chance of developing diabetes during their lifetimes; the risk to non-First Nations individuals is 50%.[20]

In its brief, the Canadian Indigenous Nurses Association (CINA) explained that:

[t]he complex interaction of access to appropriate and equitable care related to socioeconomic status, geography, infrastructures, language and cultural barriers, jurisdictional issues demonstrate the multifactorial causes of types 2 diabetes in Indigenous population[s].[21]

Federal Diabetes-related Initiatives

The Canadian Diabetes Strategy, which was established in 1999, became part of the Integrated Strategy on Healthy Living and Chronic Disease in 2005. The Committee heard from Gerry Gallagher, Executive Director, Centre for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Equity, Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention Branch from PHAC that PHAC takes “an integrated approach to promote healthy living and prevent chronic disease.”[22] Valerie Gideon explained that there has been a shift from disease-specific strategies to a “holistic framework approach.”[23]

PHAC conducts national surveillance of diabetes in collaboration with provinces and territories, and through the Pan-Canadian Health Inequalities Reporting Initiative (which is a partnership between PHAC, provinces and territories, Statistics Canada, the Canadian Institute for Health Information and the First Nations Information Governance Centre) has gained “new insights into how diabetes impacts different groups of Canadians in different contexts.”[24]

PHAC has also developed CANRISK, which is a questionnaire used to identify an individual’s risk of developing diabetes. It also provides information on reducing risk.[25] The Committee heard that PHAC promotes healthy living and chronic disease prevention through several programs and partnerships.[26]

The Government of Canada and JDRF jointly support type 1 diabetes research through a $30‑million partnership between JDRF and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.[27]

Federal Programs to Help Reduce Diabetes Rates in Indigenous Communities

As Roslyn Baird, Chair of the National Aboriginal Diabetes Association explained to the Committee, diabetes complications “are devastating our communities.” She noted that the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Call to Action 19 set out that “[A]boriginal health is a direct result of government policies, including residential schools, and it is only through change that the health gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples can be closed.”[28]

To support community-based health promotion and disease prevention, Indigenous Services Canada provides $44.5 million annually for the Aboriginal Diabetes Initiative.[29] The Aboriginal Diabetes Initiative was part of the Canadian Diabetes Strategy, launched in 1999. Nutrition education is provided in many communities through the Nutrition North Canada program. Diabetes treatment supports are also offered through Indigenous Services Canada’s Non-Insured Health Benefits Program.[30]

With respect to chronic disease prevention more generally, a specific framework for Indigenous peoples has been developed to provide “broad direction and identif[y] opportunities to improve access for individuals, families, and communities to appropriate, culturally relevant services and supports based on their needs at any point along the health continuum.”[31]

The Effects of Diabetes

Physical Health

As Diabetes Canada explains in Diabetes 360°, A Framework for a Diabetes Strategy for Canada, 30% of strokes, 40% of heart attacks, 50% of kidney failures that requires dialysis and 70% of limb amputations not caused by accidents are diabetes-related.[32] Diabetic foot ulcers, which are a common diabetes complication, can lead to amputation if not treated properly. Dr. Catharine Whiteside, Executive Director, Diabetes Action Canada, explained that a foot ulcer in an individual with diabetes is an indication that that individual may have poor glucose control and may be at risk of other complications.[33] She noted that Alberta Health Services found that 85% of amputations are preventable.[34] Peripheral and other types of neuropathy (damage to nerves) can also result from diabetes.

Children affected by type 2 diabetes have more complications at diagnosis than adults, often requiring insulin injections for treatment.[35]

As Victor Lepik, an individual living with type 1 diabetes told the Committee,

While I'm very conscientious about keeping my diabetes under control, managing my blood sugar is a juggling act. Over the years, I've struggled with low blood sugar and dangerously high blood sugar. Untreated, severe low blood sugar can result in seizures, loss of consciousness and even death. In order to keep my blood sugar under control, I typically require five to seven daily injections of insulin. I also check my blood sugar levels at least 10 times a day to ensure that they're neither too high nor too low.[36]

Individuals with type 1 diabetes can also have difficulty managing blood glucose levels during periods of illness and sustained high blood glucose levels can lead to diabetic ketoacidosis,[37] which can require hospitalization.

“While I'm very conscientious about keeping my diabetes under control, managing my blood sugar is a juggling act.”

Victor Lepik, an individual living with diabetes

Mental Health and Stigma

Dr. Mélanie Henderson stated that youth with type 2 diabetes are more at risk for depression. If they are obese, they can have low self-esteem and body image, and are often victims of bullying.[38] Dr. Bruce Verchere told the Committee that individuals with diabetes are “at greatly increased risk for mental health issues, including anxiety and depression.”[39] Karen Kemp, who has type 1 diabetes, told the Committee that 50% of individuals living with diabetes suffer from depression.[40] As Charlene Lavergne, who lives with diabetes and appeared as an individual, explained to the Committee: “You get depressed. You can't get help. There are no psychiatrists. There are no psychologists. There is nothing out there. There's nobody to talk to about our issues.”[41]

Ms. Lavergne acknowledged that stigma contributes to poor diabetes management:

In my family, there are 35 diabetics and we don't talk about it. I have to do my blood sugar under the table when I visit my mother. We don't discuss it, and they don't treat.

Last year I lost my uncle to it because they just won't treat. They won't admit to it. They don't want to deal with it because the stigma is so bad.[42]

Louise Kyle, who has type 1 diabetes, noted that stigma is a problem for individuals with diabetes, and that public education on diabetes could be a useful tool to reduce stigma.[43]

There is a strong need to reduce the stigma associated with type 2 diabetes. Reducing messaging that blames patients for their diabetes is an important first step to take. Early detection of diabetes can prevent significant complications and comorbidities, reducing the strain on the health care system.

“Last year I lost my uncle to it because they just won't treat. They won't admit to it. They don't want to deal with it because the stigma is so bad.”

Charlene Lavergne, an individual living with diabetes

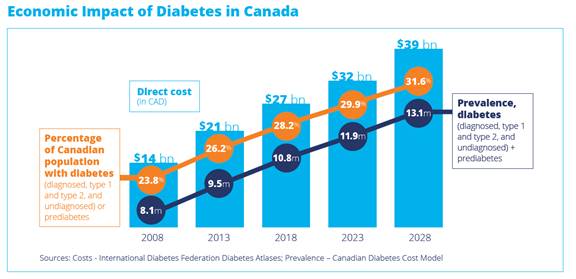

Health Care Costs

Canada is among the top 10 OECD countries for health care spending relating to diabetes.[44]

Figure 1

Source: Diabetes Canada, Diabetes 360°: A Framework for a Diabetes Strategy for Canada, Executive Summary, July 2018.

Kimberley Hanson, Director, Federal Affairs, Government Relations and Public Policy, Diabetes Canada, stated that implementing proven prevention programs across Canada could result in health care savings of $1.24 billion over 10 years.[45]

Barriers to Management

For some individuals with diabetes, accessing health care services to manage their diabetes is challenging and can involve long wait times and significant travel time.[46] To address issues relating to access to health care services for individuals living with diabetes in remote communities, Stacey Livitski, who has type 1 diabetes and appeared as an individual, recommended that there need to be incentives for health care professionals to work in northern communities.[47]

Other barriers include a lack of education and awareness both for individuals who have or may have diabetes, as well as health care professionals. Indigenous peoples in Canada face unique barriers. These barriers are described below.

Education and Awareness

General

“The most economical, effective, and efficient way to solve diabetes related problems, from prevention to intervention, morbidity and mortality, is through education.”

Professor Nam H. Cho, President of the International Diabetes Federation

In his brief to the Committee, Professor Nam H. Cho, President of the International Diabetes Federation, explains that “[t]he most economical, effective, and efficient way to solve diabetes related problems, from prevention to intervention, morbidity and mortality, is through education.”[48]

Michelle Corcoran, Outreach Diabetes Case Manager and dietician with Horizon Health Network in New Brunswick, told the Committee that while diabetes outcomes are improved for individuals who receive diabetes education, “many people, for many reasons, do not access the education they need.”[49] Lucie Tremblay, President of l’Ordre des infirmières du Québec, echoed the need for more education for individuals with diabetes so that they can better manage the disease.[50]

The Committee believes that public awareness and education are instrumental to prevent the onset of type 2 diabetes. Far too many Canadians are living with diabetes or pre-diabetes without being diagnosed. Familiarizing both Canadians and health care professionals with the symptoms and warning signs of diabetes can help reduce the number of Canadians that develop type 2 diabetes and ultimately help to relieve the resulting and increasing burden on our health care system.

Health Care Professionals

The Committee heard that diabetes-related training is not part of initial college training for nurses in Quebec,[51] and that not all health care practitioners use clinical practice guidelines to screen for diabetes.[52] Michelle Corcoran indicated that while 80 % of diabetes care is done in family doctors’ offices, many of them are not meeting the targets that have been set out in clinical practice guidelines.[53] Stacey Livitski referred to her experience and the need for more education for health care professionals:

[T]here are specialists out there, and we know more than our specialists do about diabetes. We're going for appointments and essentially getting nothing in return from our health care professionals[54]

Some individuals have had negative interactions with health care professionals in relation to their diabetes. Charlene Lavergne shared this observation with the Committee:

I had a surgeon tell me that he didn't believe in type 2 diabetes or whatever my diabetes was, and he wouldn't order insulin. It took me a year and a half to heal. He wouldn't give me insulin. He just didn't believe in it. There are a lot of doctors who don't believe in my type of diabetes.… “You're too fat. You don't exercise enough. You've never done the right thing, so it's your fault.” I'm telling you honestly, they always blame that.[55]

Indigenous Peoples

Lifestyle over the past 50 years has had a great deal of impact, and serious impact, on the health of Indigenous people. Our elders have expressed their sadness, because diabetes is killing our people. This is what it is, a killer.[56]

The Canadian Indigenous Nurses Association has identified a number of barriers in the delivery of diabetes-related health care services to Indigenous communities, including:

[T]he geographic locations of communities …, the lack of healthcare workers and the social determinants of health (e.g., housing, water, infrastructure and access to nutritious food), the lack of culturally appropriate diabetes programs and services that are developed in collaboration with Indigenous communities and the lack of a regular surveillance data on Indigenous health.[57]

When she appeared before the Committee, Marilee Nowgesic, Executive Director, CINA also referred to “the colonial legacy of health care where [I]ndigenous people are experiencing poor impacts, poor access to health care, racism and blaming.”[58]

She also discussed the role technology could play in improving Indigenous health outcomes, particularly for youth. The Committee heard from Reliq Health Technologies that remote patient monitoring can be used to help manage diabetes; Reliq has used this technology as part of a pilot project in Sioux Lookout, which is three hours north of Thunder Bay, Ontario.[59] However, Ms. Nowgesic pointed out that some First Nations have limited connectivity, which is a barrier in some communities to accessing self-care tools that could support diabetes management.[60]

Lifestyle over the past 50 years has had a great deal of impact, and serious impact, on the health of [I]ndigenous people. Our elders have expressed their sadness, because diabetes is killing our people. This is what it is, a killer.”

Marilee Nowgesic, Executive Director, Canadian Indigenous Nurses Association

Dr. Agnes Coutinho, Past Chair of the National Aboriginal Diabetes Association (NADA) recommended to the Committee that “the Government of Canada acknowledge that diabetes among Indigenous peoples of Canada is a systemic disease at pandemic levels and requires immediate attention.”[61] NADA expressed the need to:

- 1) support Indigenous-led diabetes programs, services and research;

- 2) prioritize food sovereignty;

- 3) provide access to appropriate care and treatment options and to traditional healers and medicines;

- 4) raise awareness about gestational diabetes and the increase in diabetes among young Indigenous women.[62]

CINA also emphasized the need to address food security for Indigenous populations and the importance of cultural competency and cultural safety training for health care practitioners.[63]

Costs Associated with Diabetes-Related Treatment and Management Tools

Kimberley Hanson explained that individuals with diabetes can spend up to $15,000 per year in out-of-pocket expenses,[64] and in their joint brief to the Committee, Universities Allied for Essential Medicines, T1 International, Santé Diabète and 100 Campaign noted that 57% of Canadians living with diabetes cannot adhere to their therapies because of their cost.[65] Dr. Catharine Whiteside explained that people with diabetes and early signs of kidney disease may not be able to afford the medications they need, which can be quite expensive. Not adhering to treatment in these cases can lead to end-stage kidney disease which requires dialysis. The annual cost of dialysis per patient is $70,000.[66]

Louise Kyle, who has type 1 diabetes and who appeared on behalf of the 100 Campaign and Universities Allied for Essential Medicines also discussed cost barriers and access to diabetes treatment:

Low-income Canadians are disproportionately affected by the high costs of treating diabetes. They have a higher risk of cardiovascular complications and death compared to individuals with higher socio-economic status. A study estimated that 5,000 deaths in Ontario alone could have been prevented with universal drug coverage for diabetes supplies.

Diabetes-related mortality is as much as three times higher for [I]ndigenous populations in Canada than for non-indigenous populations. A recent policy round table found that these challenges can be linked to “variability across the country in terms of public and private insurance coverage for medications and supplies for those managing their diabetes.” [67]

As is referenced by Ms. Kyle above, not all medications used for treatment for diabetes are covered by provincial/territorial health insurance plans. As Dave Prowten explained, “giving people the most basic of tools to manage their type 1 diabetes, which is insulin, is a very important step that could be taken to prevent … deaths.”[68] The Committee also heard that, despite the fact that Frederick Banting, Charles Best and J.B. Collip assigned their insulin patent rights to the Board of Governors of the University of Toronto for $1 each, the cost of insulin has increased substantially in recent years.[69] Charlene Lavergne explains the difficulty she faces in accessing medications because of their cost:

I live on $1,500 a month. My insulins are $1,000. My rent is $1,000. If you can afford your medication, it's great, but if you can't.... I just beg. I go from clinic to doctor, and I get compassionate care, but I never know when it's going to run out, and I never know when I'm going to get my next batch, so it's really a struggle.[70]

Michelle Corcoran expressed her frustration to the Committee with respect to coverage of insulin by provincial insurance plans:

Should I have to make people choose between picking up insulin or getting groceries? Should they have to shop pharmacies to get the best price for insulin? These are things I deal with every day. It's frustrating, as well, when I have a plan that can provide some coverage but still people are denied that coverage, not because they didn't meet the criteria set out by our government, but because the people who are advising this plan have wrongly read the forms, or they inexplicably say that this is denied when it shouldn't be.

I shouldn't have to advocate for patients. There shouldn't be this issue.[71]

Even when some medications are covered by provincial plans, some related supplies, such as syringes and test strips for blood glucose monitors, are not. As Kimberley Hanson told the Committee, “[i]nsulin doesn’t do much good if you haven’t a syringe to inject it.”[72] Test strips for blood glucose monitors are $1.50 per strip.[73]

Canadians are proud of our publicly funded health care system, a system that is based on need and not on ability to pay. However, the Committee believes that when Canadians living with diabetes cannot afford their medical supplies and equipment, something has to change. Canadians living with diabetes expressed the need for more accessible treatment. A solution to provide Canadians with the medical supplies and equipment that they need to live with diabetes must be found.

“Should I have to make people choose between picking up insulin or getting groceries? Should they have to shop pharmacies to get the best price for insulin? These are things I deal with every day.”

Michelle Corcoran, Outreach Diabetes Case Manager, Dietitian, Diabetes Education, Horizon Health Network

Individuals who require insulin therapy can have insulin delivered by injection or by an insulin pump. Insulin pumps cost approximately $7,000, and coverage for them under provincial plans can vary by age depending on an individual’s place of residence. Continuous glucose monitors (CGM) are also available. A CGM contains a thin cannula, attached to a transmitter, that is inserted under the skin. It monitors blood glucose levels at frequent intervals, requiring fewer finger pricks than other glucose monitors to check blood glucose levels. No provincial plans cover CGMs, which cost approximately $3000 to $4000 annually;[74] some private plans provide coverage.

There is data suggesting that the use of insulin pumps by individuals who are good candidates for insulin pump therapy prevents long-term complications, which results in health care savings.[75] For some individuals, insulin pumps greatly contribute to managing their blood glucose levels: “When I got my insulin pump eight years ago, I caught the flu and didn't realize how significant it was, because it was the first time I didn't go into diabetic ketoacidosis. That was a life changer for me.”[76]

With respect to foot care and prevention of ulcers and amputations, Dr. Catharine Whiteside explained that in most provinces, community chiropody care is not paid for by provincial/territorial health insurance plans, which is “one of the biggest barriers to care.”[77]

The Committee believes that Canadians should have equal access to diabetes-related medical care regardless of where they live in Canada, and that reimbursement for diabetes-related supplies such as insulin pumps, glucose test strips, and lancets should be standardized across the country.

The Disability Tax Credit

Many witnesses raised concerns about accessing the Disability Tax Credit (DTC), which is a non-refundable income tax credit. The Committee heard that a number of individuals with diabetes who had previously been approved for the DTC have subsequently had their claims rejected. While the Canada Revenue Agency reviewed cases that had been denied, the Committee heard that 42% were re-rejected.[78] Individuals whose applications were rejected were also required to close a registered disability savings plan (RDSP) if they had one, and government contributions to the RDSP were to be clawed back.[79]

Dave Prowten indicated that “JDRF is committed to working with the government and the newly created disability advisory committee,”[80] and recommended (among other things) that the number of hours per week for life-sustaining therapy that are required to qualify for the DTC be reduced from 14 to 10.[81]

Marilee Nowgesic noted the burden on health care professionals of having to complete benefit-related forms, and the cost burden on patients who have to pay to have the form filled out.[82] Charlene Lavergne told the Committee “the forms need to change. They need to be more adaptive. I think it would help if we had a tailored form for just diabetes.”[83] Louise Kyle explained that applying for the DTC is

… a huge burden to put on someone who is already dealing with something 24 hours a day—to be put through this sort of administrative process of coming up with 14 hours a week of things that don't even scratch the surface of what someone with diabetes has to deal with.[84]

Diabetes Abroad: A Snapshot

Research and international experience show that with coordinated, focused action we can turn the tide [of diabetes], saving valuable health care resources and improving millions of lives.[85]

In his brief to the Committee, Prof. Nam H. Cho, noted that there are 425 million people globally who live with diabetes.[86] He explained that “diabetes threatens to overwhelm healthcare systems as well as budgets. An estimated 12% of global health expenditure (or 727 billion US dollars) is now spent on diabetes.”[87]

Research and international experience show that with coordinated, focused action we can turn the tide [of diabetes], saving valuable health care resources and improving millions of lives.”

Dr. Jan Hux, President, Diabetes Canada

The World Health Organization recommends that all countries have a national diabetes strategy.[88] In 2016 in Singapore, where one in three people is at risk of developing diabetes, the Ministry of Health launched a “War on Diabetes,” and established a taskforce to take a whole-of-nation approach to addressing diabetes.[89] Singapore’s approach has included public education and stakeholder engagement through the campaign, “Let’s BEAT Diabetes”; Be Aware, Eat Right, Adopt an Active Lifestyle, and Take Control. Singapore has also made diabetes one of the Ministry of Health’s priority areas for research and development.[90]

The Committee also heard about Sweden’s diabetes register, which tracks the personal health information of individuals with diabetes. As Dr. Whiteside explained, maintaining this register has led to “some of the best diabetes outcomes in the world at a much lower cost than expended per capita in Canada.”[91] In Sweden, 90% of individuals with diabetes are part of the registry.[92]

A National Diabetes Strategy for Canada

Currently today, we have no overarching framework, no guidelines, no standards that we're working towards, no targets that we're working towards in any kind of coordinated way.

We think that [a] strategy can really help achieve that.[93]

Many witnesses emphasized the need for federal leadership and coordination relating to diabetes. As Dr. Jan Hux, President, Diabetes Canada, stated, “Diabetes is just not a top priority in our country. But it must be.”[94]

Pointing to initiatives such as the Canadian Partnership Against Cancer and the Mental Health Commission of Canada, Dr. Hux explained that “[p]rovinces and territories each working on diabetes in their own way will not facilitate the economies of scale and rapid knowledge sharing that are the hallmarks of transformative change.”[95]

Diabetes Canada recommends that the federal government “establish a national partnership and invest $150 million in funding over seven years to support the development and implementation of a new nation-wide diabetes strategy, based on the Diabetes 360° framework, and … facilitate the creation of Indigenous-specific strategic approaches led and owned by Indigenous groups.”[96]

In collaboration with numerous stakeholders, and based on the approach used for HIV/AIDS and other diseases, Diabetes Canada developed the following targets relating to diabetes, to be achieved within the seven years of federal funding:

- 90 % of Canadians live in an environment that preserves wellness and prevents the development of diabetes

- 90% of Canadians are aware of their diabetes status

- 90% of Canadians living with diabetes are engaged in appropriate interventions to prevent diabetes and its complications

- 90% of Canadians engaged in interventions are achieving improved health outcomes.[97]

Components of a Canadian Diabetes Strategy

Diabetes Canada’s proposed strategy focuses on prevention, screening and treatment. It also contains recommendations specific to type 1 diabetes and draws attention to the “unique needs of Indigenous populations.”[98]

Specifically, the national partnership that Diabetes Canada recommends would have the following mandate:

[T]o collaborate with provincial, territorial and, if appropriate and agreeable, Indigenous governments along with academia, industry and non-governmental organizations to further plan and implement an approach to the prevention and management of diabetes in Canada. The partnership should facilitate the creation of Indigenous-specific strategic approaches led and owned by any Indigenous groups wishing to embrace this framework. The goal of this partnership would be to collaborate with healthcare systems to optimize disease prevention and healthcare delivery for people with diabetes, with a goal of sunsetting itself as quickly as possible.[99]

Research and Funding

As is mentioned above, as part of its 360° Framework, Diabetes Canada recommends that the federal government invest $150 million over seven years to support a national diabetes strategy.[100] The strategy includes the need to expand research on preventing and treating type 1 and type 2 diabetes.[101] Diabetes researcher Dr. Bruce Verchere highlighted Canada’s significant role in diabetes research:

As we approach the 100th anniversary of the discovery of insulin by Fred Banting and colleagues at the University of Toronto in 1921, it's important to point out that Canadian researchers have played pivotal roles in the development of a number of other therapies in worldwide use for the treatment of diabetes. These include not just insulin, of course, but also newer classes of drugs used in type 2 diabetes known as DPP-4 inhibitors and GLP-1 analogues.

In addition, the Edmonton Protocol for clinical transplantation of islets, the clusters of insulin-producing cells in the pancreas called beta cells, is recognized worldwide, and has made replacement of insulin-producing beta cells by transplantation a clinical reality, albeit one that's not yet widely available and needs further research. Canadian diabetes researchers are now playing a leading role in research that aims to develop insulin-producing cells from stem cells that would be suitable for transplantation into persons with type 1 diabetes.[102]

With respect to type 1 diabetes specifically, research funding in the U.S. is $150 million per year; Australia has committed $125 million over nine years.[103] JDRF recommends that Canada needs “to make significant investments in cure and prevention research” for type 1 diabetes.[104]

Dr. Mélanie Henderson echoed the need for research funding, including research on pediatric obesity.[105] Dr. Bruce Verchere explained the value in funding diabetes-related research:

[T]here's really some remarkable diabetes research going on across the country and … Canada is truly uniquely poised to continue its world-leading role in diabetes research and make new discoveries and contributions that stand to change the lives of persons living with, or at risk for, the disease. Government support of research is critical if this is to happen.[106]

Dr. Verchere noted the importance of funding “the best diabetes research:”

Increasing fundamental support across pillars and across research disciplines through the tri-council funding, particularly CIHR, ensures that the best diabetes research is funded across the country and that diabetes research capacity in Canada remains strong. When research capacity is strong, this government support of diabetes research in Canada is enhanced, for example, through Canadian participation in international teams and magnified by additional support from international organizations such as JDRF and the U.S. National Institutes of Health, and nationally from Diabetes Canada.[107]

Disease Registry, Standardization and Screening

The Committee heard that there is a need to track patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes to gather data.[108] Tracking patient outcomes in communities “will enable continual quality improvement based on best evidence,”[109] and assist in determining whether prevention and other interventions are successful.[110] Diabetes Action Canada has developed a national diabetes repository.[111]

JDRF Canada is supporting a nationwide study exploring the lifespan of type 1 diabetes patients. The study involved establishing a diabetes registry of Canadians who had been living with type 1 diabetes for 50 years or more.[112] The Committee suggests that the registry that was established be reviewed to see whether it could be expanded to include all Canadians living with type 1 and type 2 diabetes. This could become an essential resource relating to treatment research, as well as for supporting outreach in relation to treatment.

Dr. Catharine Whiteside told the Committee that Diabetes Action Canada recommends that provinces and territories work towards standardizing diagnosing diabetes and complications.[113] It also recommends that care, treatment and the education of health care professionals should be standardized and made available regardless of where an individual resides.[114]

With respect to screening for diabetes, the Committee heard that diabetes screening and prevention are very important for First Nations people living in remote or isolated communities.[115] In addition, Diabetes Action Canada recommends that a national diabetes strategy include support for screening for diabetic eye disease, diabetic foot ulcers and kidney disease.[116]

With respect to type 1 diabetes, children could be potentially screened to look for biomarkers.[117]

Diabetes Strategies for Indigenous Peoples

We have seen an ongoing opportunity for this government to support the request to work with your respective caucuses to call on the government to provide funding to explore the establishment and administration of diabetes strategies for [I]ndigenous people, using [I]ndigenous knowledge-based healing models such as the Four Directions. This would include terms for renewable funding and evaluation for success that is mutually agreed upon by the federal government and national [I]ndigenous health professional associations.[118]

Isabelle Wallace, Indigenous Nursing Advisor with CINA stated that “[d]iabetes prevention will take on a new perspective once Indigenous knowledge is mobilized.”[119] Marilee Nowgesic explained the need to include Indigenous knowledge and healing practices as part of chronic disease management,[120] and in its brief, CINA recommended that Indigenous youth be consulted to establish priorities relating to preventing diabetes.[121]

Finally, Diabetes Action Canada noted in its brief that

[t]he recently published Diabetes Canada Guidelines emphasize the urgent need to implement screening and prevention strategies in collaboration with Indigenous community leaders, Indigenous peoples with diabetes, health‐care professionals and funding agencies to promote environmental changes and prevent the risk of diabetes in all Indigenous populations.[122]

Conclusion

Diabetes Canada has developed a national framework for Canada to defeat diabetes. Supporting Diabetes 360°: A Framework for a Diabetes Strategy for Canada has the potential to enhance the prevention, screening and management of diabetes and achieve better health for Canadians. It will reduce unnecessary health care spending by billions of dollars, protect Canada’s productivity and competitiveness and improve the lives of millions of Canadians.

The Committee therefore recommends:

Recommendations

National Diabetes Strategy

Recommendation 1

That the Government of Canada, in partnership with the provinces and territories, and in collaboration with stakeholders such as Diabetes Canada, plan and implement an approach to the prevention and management of diabetes in Canada through a national diabetes strategy, as outlined in Diabetes Canada’s Diabetes 360°: A Framework for a Diabetes Strategy for Canada. The partnership should facilitate the creation of Indigenous-specific strategic approaches led and owned by any Indigenous groups wishing to embrace this framework.

Recommendation 2

That, as part of the national diabetes strategy, the Government of Canada, in partnership with the provinces and territories, and in collaboration with stakeholders such as Diabetes Canada:

- explore options for establishing a national diabetes registry for people living with both type 1 and type 2 diabetes;

- explore options to reduce diabetes-related stigma; and

- explore options to improve public awareness and education on diabetes, particularly through community programming, including public awareness of the relationship between nutrition and diabetes.

Research Funding

Recommendation 3

That the Government of Canada provide funding through the Canadian Institutes of Health Research for research into preventing and treating type 1 and type 2 diabetes.

Disability Tax Credit and Diabetes

Recommendation 4

That the Government of Canada provide greater certainty to individuals with diabetes about their eligibility for the disability tax credit and ensure the rules related to life-sustaining therapy and associated requirements accommodate Canadians living with diabetes.

Recommendation 5

That the Government of Canada reduce the required number of hours spent on therapy-related activities per week in order for an individual to be eligible for the disability tax credit.

Recommendation 6

That the Government of Canada amend the Income Tax Act to include the time spent on certain activities, such as preparing meals or preparing and making adjustments to the intake of medical food (defined as a suitable diet prescribed by a medical practitioner) or formula that are required to manage diabetes, in the time requirement for therapy-related activities under the disability tax credit.

Provincial/Territorial Coverage of Diabetes-Related Medications, Supplies and Equipment

Recommendation 7

That the Government of Canada hold discussions with the provinces and territories to explore possible approaches to providing uniform coverage for diabetes-related medications, supplies and equipment across Canada. A solution to provide Canadians with the medical supplies and equipment that they need to live with diabetes must be found.

Cost of Insulin

Recommendation 8

That the Government of Canada, in collaboration with the provinces and territories, the Pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance and the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board, identify ways of addressing the high prices of long-acting insulin in Canada.

Rural, Remote and Northern Communities

Recommendation 9

That the Government of Canada hold discussions with the provinces and territories to explore possible approaches to improving access to health care for individuals living with diabetes in rural, remote and northern communities.

Access to Physicians

Recommendation 10

That the Government of Canada hold discussions with the provinces and territories to explore possible approaches to addressing the difficulties faced by many Canadians in accessing a family physician.

Diabetes-Related Education and Training for Health Care Professionals

Recommendation 11

That the Government of Canada work with the provinces and territories and their health professional regulatory bodies to ensure that health care professionals receive comprehensive education and training to properly identify and manage diabetes and diabetes-related complications in their patients.

[1] House of Commons, Standing Committee on Health (HESA), Evidence, 42nd Parliament, 1st Session, 2 October 2018, 0945 (Kimberley Hanson, Director, Federal Affairs, Government Relations and Public Policy, Diabetes Canada).

[2] Diabetes Canada, Diabetes 360°: A Framework for a Diabetes Strategy for Canada, July 2018, p. 4.

[3] HESA, Minutes of Proceedings, 42nd Parliament, 1st Session, 21 March 2017.

[4] Public Health Agency of Canada [PHAC], Diabetes in Canada: Facts and figures from a public health perspective, 2011.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Diabetes Canada, Diabetes 360°: A Framework for a Diabetes Strategy for Canada, July 2018, p. 13.

[7] HESA, Evidence, 28 May 2018, 1530 (Gerry Gallagher, Executive Director, Centre for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Equity, Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention Branch, Public Health Agency of Canada).

[8] Diabetes Canada, Diabetes 360°: A Framework for a Diabetes Strategy for Canada, July 2018, p. 13.

[9] HESA, Evidence, 2 October 2018, 0900 (Dave Prowten, President and Chief Executive Officer, Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation Canada).

[11] HESA, Evidence, 23 October 2018, 0910 (Bruce Verchere, Professor, Department of Surgery, Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of British Columbia).

[12] Ibid.

[14] Ibid., 1630 (Catharine Whiteside, Executive Director, Diabetes Action Canada).

[15] Ibid., 1615 (Jan Hux).

[16] HESA, Evidence, 23 October 2018, 0845 (Deljit Bains, Leader, South Asian Health Institute, Fraser Health).

[17] HESA, Evidence, 28 May 2018, 1625 (Mélanie Henderson, Pediatric Endocrinologist and Associate Professor, Centre hospitalier universitaire Sainte-Justine).

[18] Ibid., 1535 (Valerie Gideon, Senior Assistant Deputy Minister, First Nations and Inuit Health Branch, Department of Indigenous Services Canada).

[19] Canadian Indigenous Nurses Association, Submission to the Standing Committee on Health, 23 May 2018.

[21] Canadian Indigenous Nurses Association, Submission to the Standing Committee on Health, 23 May 2018.

[23] Ibid., 1555 (Valerie Gideon).

[24] Ibid., 1530 (Gerry Gallagher).

[25] Ibid.

[26] Ibid.

[28] HESA, Evidence, 28 May 2018, 1615 (Roslynn Baird, Chair, National Aboriginal Diabetes Association).

[29] Ibid., 1535 (Valerie Gideon).

[30] Ibid.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Diabetes Canada, Diabetes 360°: A Framework for a Diabetes Strategy for Canada, July 2018, p. 5.

[34] Ibid., 0850 (Catharine Whiteside).

[37] “Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) is a life-threatening problem that affects people with diabetes. It occurs when the body starts breaking down fat at a rate that is much too fast. The liver processes the fat into a fuel called ketones, which causes the blood to become acidic.” National Institutes of Health, U.S. National Library of Medicine, MedLine Plus.

[41] Ibid., 0950 (Charlene Lavergne, as an individual).

[42] Ibid.

[43] HESA, Evidence, 22 November 2018, 0920 (Louise Kyle, North American Coordinating Committee Member, Advocate with the 100 Campaign, Universities Allied for Essential Medicines).

[44] Diabetes Canada, Diabetes 360°: A Framework for a Diabetes Strategy for Canada, July 2018, p. 4.

[47] Ibid., 0915 (Stacey Livitski, as an individual).

[48] Prof. Nam H. Cho, Recommendations on What Canada Could do to Reduce the Impact or Prevalence of Diabetes.

[49] HESA, Evidence, 22 November 2018, 0850 (Michelle Corcoran, Outreach Diabetes Case Manager, Dietitian, Diabetes Education, Horizon Health Network).

[50] HESA, Evidence, 23 May 2018, 1625 (Lucie Tremblay, President, Ordre des infirmières du Québec).

[51] Ibid.

[55] Ibid., 0855 (Charlene Lavergne).

[56] HESA, Evidence, 23 May 2018, 1635 (Marilee Nowgesic, Executive Director, Canadian Indigenous Nurses Association).

[57] Canadian Indigenous Nurses Association, Submission to the Standing Committee on Health, 23 May 2018.

[59] Ibid., 0855 (Richard Sztramko, Chief Medical Officer, Reliq Health Technologies).

[60] Canadian Indigenous Nurses Association, Submission to the Standing Committee on Health, 23 May 2018.

[61] HESA, Evidence, 28 May 2018, 1620 (Agnes Coutinho, Past Chair of the National Aboriginal Diabetes Association).

[62] Ibid.

[63] Canadian Indigenous Nurses Association, Submission to the Standing Committee on Health, 23 May 2018.

[65] Essential Medicines, T1 International, Santé Diabète, 100 Campaign, Submission to the Standing Committee on Health : A call for Canada to uphold the rights of people living with diabetes at home and abroad, 22 October 2018.

[69] HESA, Evidence, 20 November 2018, 0935 (Charlene Lavergne); and HESA, Evidence, 22 November 2018, 0905 (Louise Kyle).

[75] Ibid., 0930 (Kimberley Hanson).

[78] Ibid., 0855 (Kimberley Hanson).

[79] Ibid.

[81] Ibid.

[86] Prof. Nam H. Cho, Submission to the Standing Committee on Health, Recommendations on What Canada Could do to Reduce the Impact or Prevalence of Diabetes.

[87] Ibid.

[89] Ministry of Health, Singapore, Submission to the Standing Committee on Health, Singapore’s War on Diabetes, August 2018.

[90] Ibid.

[93] Ibid., 0925 (Kimberley Hanson).

[95] Ibid.

[96] Diabetes Canada, Diabetes 360°: A Framework for a Diabetes Strategy for Canada, July 2018, p. 1.

[97] Ibid., p. 4.

[98] Ibid., p. 23.

[99] Ibid., p. 25.

[100] Ibid., p. 4.

[101] Ibid., p. 13.

[104] Ibid.

[107] Ibid., 0915.

[111] Diabetes Action Canada, Submission to the Standing Committee on Health, 16 May 2018.

[112] See JDRF Canada, News Release, “Canadians Living With Type 1 Diabetes for 50 Years Can Have a Significant Impact in Discovering Factors for Success in T1D Research,” 17 October 2013.

[114] Ibid., 0900 (Kimberley Hanson).

[116] Diabetes Action Canada, Submission to the Standing Committee on Health, 16 May 2018.

[119] Ibid., 1640 (Isabelle Wallace, Indigenous Nursing Advisor, Canadian Indigenous Nurses Association).

[120] Ibid., 1635 (Marilee Nowgesic).

[121] Canadian Indigenous Nurses Association, Submission to the Standing Committee on Health, 23 May 2018.

[122] Diabetes Action Canada, Submission to the Standing Committee on Health, 16 May 2018.