HESA Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

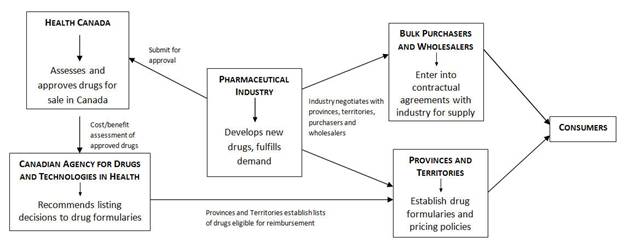

DRUG SUPPLY IN CANADA: A MULTI-STAKEHOLDER RESPONSIBILITYINTRODUCTIONOn 13 March 2012, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Health (the Committee) adopted a motion to undertake a short study on drug supply in Canada. The motion requested that, over the course of three meetings, the Committee: [E]xamine the role of government and industry in determining drug supply in Canada, how the provinces and territories determine what drugs are required in their jurisdiction, how the industry responds to them, and the impact this has on stakeholders. During meetings on 27 and 29 March, as well as 3 April 2012, the Committee heard from Health Canada officials, representatives of the pharmaceutical industry, healthcare professionals, pharmaceutical wholesalers and bulk purchasers, and patient advocates. This report outlines the role played by these stakeholders, summarizes the concerns that were expressed and offers recommendations that may mitigate future disruptions in the drug supply. THE DRUG SUPPLY CHAIN IN CANADAOnce Health Canada has authorized a drug, producers and purchasers are free to enter into commercial contracts for supply. Drug companies manufacture and supply needed medications; provinces and territories make the arrangements with suppliers to purchase them... Health Canada has no role or involvement in this regard. Paul Glover, Health Canada, 3 April 2012 The Committee heard from stakeholders along the spectrum of the drug supply chain. Health Canada, the federal drug regulator, is responsible for assessing the safety, efficacy and quality of drugs, and approving those found to have an acceptable risk/benefit profile. Health Canada is responsible for enforcing regulatory requirements of approved drugs including labelling, packaging, importing and good manufacturing practices. Drugs that have not been approved by Health Canada cannot be marketed in Canada. All provinces have publicly funded drug plans for certain populations (essentially, the elderly and those on social assistance). The drugs that these plans will reimburse are listed on each province’s drug formulary. Determination of whether a drug becomes listed on provincial formularies is assisted by the work of the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH). CADTH is an independent, not-for-profit body funded by the federal, provincial and territorial governments (except Quebec). CADTH is responsible for the Common Drug Review (CDR) process. All publicly funded drug plans participate in the CDR (except for Quebec); this includes six federal,[1] nine provincial and three territorial drug plans. The CDR assesses the clinical efficacy and cost-effectiveness of drugs approved by Health Canada against other drug therapies and provides listing advice to participating drug plans. CADTH indicated that although it has no expertise in the realm of drug purchasing, its current responsibilities and close ties to other provincial and territorial governments would suggest that it perhaps could play a greater role in a drug shortages strategy. The Canadian Association for Pharmacy Distribution Management (CAPDM) described itself to the Committee as the voice of the pharmacy supply chain in Canada as it brings together pharmaceutical wholesalers, self-distributing pharmacy chains and drug manufacturers. Pharmaceutical wholesalers and self-distributing pharmacy chains are responsible for over 95% of the pharmaceuticals distributed to community and hospital pharmacies as well as long-term and specialized healthcare facilities. CAPDM’s role is the management of the drug supply chain. The Committee learned that the CAPDM network becomes part of the allocation process when a medicine is in short supply as it helps ensure fair and even distribution of the affected product across the country, based on historical usage patterns. According to CADTH’s environmental scan of 2011, when drug shortages have arisen, manufacturers have sometimes been reluctant to share information about the disruptions. CADTH attributed this reluctance to a fear of losing competitive advantage, public backlash, legal or other considerations. RECENT SHORTAGES IN THE DRUG SUPPLYOn 14 March 2012 the following motion was passed unanimously in the House of Commons: That, in the opinion of this House, the government should: (a) in cooperation with provinces, territories and industry, develop a nationwide strategy to anticipate, identify, and manage shortages of essential medications; (b) require drug manufacturers to report promptly to Health Canada, the provinces and the territories any planned disruption or discontinuation in production; and (c) expedite the review of regulatory submissions in order to make safe and effective medications available to the Canadian public. This motion was prompted by recent events at Sandoz, a major manufacturer of generic medicines in Canada, which brought about significant shortages of critical medicines. Its manufacturing facility in Boucherville, Quebec produces 50% of generic injectable drugs used in Canadian hospitals. Sandoz received a warning letter on 18 November 2011 from the United States’ Food and Drug Administration (FDA) explaining that the facility was non-compliant with U.S. drug regulations. After receiving the FDA’s letter, the company slowed down production in order to address the compliance issues. The Committee heard that, in December 2011, Health Canada saw on the FDA’s Web site the warning letter to Sandoz and that the Department followed up with Sandoz to ask what their remediation plans were. Sandoz initially planned to suspend production of several non-essential products in order to focus their available production capacity on medically necessary products. Nevertheless, the Committee was told that Sandoz announced on 17 February 2012 an immediate reduction in available supply of essential medications. The Committee was not told why Sandoz’s plan to focus on essential medicines was not successful. On 2 March 2012, the Minister of Health wrote a letter to Sandoz concerned about the company’s failure to voluntarily provide publicly available, clear, precise and timely information regarding supply disruptions as this was contrary to an agreement it had signed onto the previous fall.[2] A fire broke out in the boiler room of the Sandoz facility in Boucherville on 4 March 2012. As a result, production was stopped completely for a week before resuming partially. While recent drug shortages prompted the introduction of the motion regarding a national strategy to manage drug shortages, similar disruptions in drug supply have been noted in past years. CHRONOLOGY OF ACTIONS TAKEN IN RESPONSE TO DRUG SUPPLY DISRUPTIONSThe Committee heard that drug shortages have been increasing in frequency and duration over the past decade and have become a serious issue for health care professionals for at least the past two years. Members were told that, in fall 2010, the Canadian Pharmacists Association (CPhA) met with a number of stakeholders, including pharmaceutical industry groups and wholesalers, to identify causes of drug shortages and that a guide to help pharmacists deal with drug shortages was published in late 2010. We've taken very seriously working with all the various stakeholders—hospital members, distributors — to create an allocation system that would minimize the shortage. Michel Robidoux, Sandoz Canada, 27 March 2012 On 27 January 2011, the Canadian Anesthesiologists’ Society wrote to the Minister of Health to express concerns regarding shortages of anesthetizing agents. On 25 March 2011, the Minister responded in a letter which explained that the Department was assessing drug shortages through contact with various stakeholders including the pharmaceutical industry, health care professionals and drug plan managers in several provinces. The Minister also wrote that departmental officials were in contact with the pharmaceutical industry to determine their preparedness to provide information about drug shortages, and that they had asked CADTH to conduct an environmental scan of drug shortages. In March 2011, the environmental scan on drug supply disruptions was published, which also provided several suggestions for strategies to manage drug shortages. In early 2011, HealthPro Procurement Services Inc. (HealthPRO), a national healthcare Group Purchasing Organization (GPO), began developing a revised contracting strategy to protect members (including provincial health authorities, hospitals, and shared service organizations) from shortages. Committee members also learned that several national health care professional organizations including the Canadian Society of Hospital Pharmacists (CSHP), as well as pharmaceutical associations have been working on a national drug supply management system since spring 2011. The Committee was also informed that, in March 2011, l’Ordre des pharmaciens du Québec (l’Ordre) formed a multi-stakeholder committee to study and identify factors causing drug shortages as well as ways to manage such shortages. The results of that study were released on 16 April 2012. To improve transparency and reduce the number of drug shortages, the Minister of Health wrote to a number of industry associations including Canada’s Research-Based Pharmaceutical Companies (Rx&D), the Canadian Generic Pharmaceutical Association (CGPA), BIOTECanada, the Canadian Medical Association (CMA), the CPhA, distributors and wholesalers in early 2011.[3] The purpose of that correspondence was to seek the collaboration of various stakeholders on two points: (a) to notify health system workers when a drug shortage arises and (b) to assist in reducing the number of future drug shortages.[4] In response to the Minister’s letter, the Multi-stakeholder Working Group on Drug Shortages (drug shortages working group) was formed and a three-phase plan was proposed.[5] The first phase, which was completed in November 2011, was the creation of two public Web sites on which the pharmaceutical industry could voluntarily post information about drug shortages in order to inform health care professionals and patients across Canada. The two public Web sites are: University of Saskatchewan — Saskatchewan Drug Information Services (SDIS)[6] and Ruptures d’approvisionnement en médicaments au Canada housed in Quebec.[7] The Committee heard that the second phase was the creation of a single bilingual Web site to provide information about drug shortages. The new site was announced in March 2012 and is available at www.drugshortages.ca. Witnesses told the Committee that the two main industry associations, Rx&D and the CGPA, committed to support funding up to $100 000 each to accelerate the development of the new Web site. Members were told that the drug shortages working group was currently working on the third phase of the plan which will offer clinical information such as alternative therapies for drugs in short supply as well as allow health practitioners to report directly into the system to validate a shortage. The Committee was also told that the national pharmaceutical associations, Rx&D and CGPA, encourage their members to post information on drug shortages using the tools developed by the drug shortages working group. Members heard that the Minister recently wrote to pharmaceutical associations to express concerns about the fact that their members were not posting drug shortage information and that instead the information was posted on company Web sites. The Committee learned that, since that letter, all members of the industry association have provided written commitments to the Minister that they will post all information on the official drug shortages site. The Committee heard that the Government of Canada has instructed the entire chain to work together and come up with a solution. Drug companies indicated that although this is a complex problem, they feel they have worked through the issues.[8] CAUSES OF DRUG SUPPLY DISRUPTIONSSecurity of supply is as important as safety, efficacy, and value to the health care of Canadians. Kathleen Boyle, HealthPRO, 27 March 2012 Disruptions in the drug supply may occur at any point along the supply chain. The regulator may identify compliance issues, the manufacturer may encounter production or market issues, purchasers may buy surplus, either intentionally or unintentionally, thereby disadvantaging other buyers, or there may be surges in demand. Several witnesses discussed the multitude of factors that could lead to disruptions in the supply of pharmaceuticals. Disruptions in supply can include the discontinuation of a pharmaceutical, as well as the interruption or reduction in production levels of a pharmaceutical. With respect to discontinuations, the Committee was told that generic medicines have a small profit margin, making it difficult to source raw materials and active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), or manufacturers may simply choose to terminate less profitable product lines. It also heard that mergers of drug manufacturing companies with similar product lines may result in consolidation and therefore change a multi-source product into a single-source product. Discontinuations of approved drugs are a foreseeable occurrence. Under the Food and Drug Regulations manufacturers must inform Health Canada within 30 days of discontinuing the sale of the product in Canada. In terms of interrupted or reduced drug supply, the Committee heard from drug manufacturers that while there has not been a change in the regulatory environment in recent years, and that the regulatory framework is similar for all major drug regulatory agencies (United States, European Union, Australia and Canada), there has been stricter enforcement. This enhanced enforcement was described as stemming from contamination of products from China and the recent surge in counterfeit products. Increased inspections and stricter follow-up on remediation actions have resulted in production slowdowns for some companies. In fact, l’Ordre informed the Committee that non-compliance issues with either Health Canada or U.S. FDA requirements identified through inspections account for 43% of drug shortages. The Committee was also told that there are sometimes transient shortages when demand outpaces supply, but that these are usually corrected without too much disruption. Unforeseen circumstances such as breakdowns along the production line and natural disasters were also listed as some of the causes of drug shortages. No concerns were raised with respect to the enforcement and compliance approach of the FDA and Health Canada. HealthPRO indicated that there has been a tendency in recent years for the generic industry to outsource its supply of raw materials and APIs which has resulted in instability in the global supply chain. Industry witnesses indicated that they often purchase their APIs from foreign sources such as China and India. CGPA claimed that the pricing restrictions placed on the generic industry by the provinces can result in limited APIs suppliers being available to the industry. It was noted that manufacturers frequently rely on a single supplier for raw materials and APIs thereby making the manufacturer vulnerable to supply disruptions should the supplier be unable to meet the manufacturer’s needs. Despite the long list of potential causes of drug shortages, all witnesses agreed that the most avoidable cause of drug supply disruptions was the tendency to award single source contracts for bulk purchases or for manufacturers to rely on single suppliers for their raw materials and APIs. All stakeholders were of the view that reliance on a single supplier introduced considerable vulnerability to the drug supply chain.

STAKEHOLDER COMMENTS1. Patient SafetyThe Committee heard that health care has changed over the years. Once dominated by surgical or short-term pharmaceutical interventions, now it is common for patients to be on long-term medication, frequently multiple prescriptions. It was told that changes to medication regimens are particularly difficult for those on long-term therapy, and that consistent supply is essential for individuals with chronic or life-threatening conditions. Witnesses described the difficulties involved when forced to find alternatives for patients. They emphasized that alternatives are sometimes more expensive, not always available, that they may be ineffective or that the adverse reactions associated with their use make them unsuitable for some patients. Additionally, a change in prescription may be accompanied with a change in the manner in which it is taken and this can present challenges for patients and their caregivers. The CSHP emphasized that their work is significantly more complex and the risk to patient is higher during drug shortages. They described their role during drug supply disruptions in identifying alternative medications, or alternative concentrations, strengths, or dosage forms of the same medication as well as compounding medications from raw materials. The Committee was told that this may introduce additional complexity to the treatment regimen and introduce opportunities for error when prescribing, preparing, administering, and monitoring medications. Finally, patient advocates spoke of the frustration and anxiety that drug shortages have on the end-users: Canadians of all ages who rely on these products to control and treat pain and illness. They emphasized the need to include patient groups in drug shortage discussions and when pursuing resolutions to the issue. 2. Sole-SourcingThe sole manufacturer of many drugs has made all players in our health care system aware of the vulnerability that comes with dependence on a single supplier. Diane Lamarre, l’Ordre, 29 March 2012 As indicated above, witnesses cited the increasing practice of GPOs, that are responsible for the bulk purchase of drugs for hospital use, of awarding sole-source contracts to generic manufacturers. While this has been done with the aim of keeping down cost, the Committee also heard that sole-source is the safest strategy for health care delivery as it reduces the amount of product-specific risk. Namely, that multiple products that may each have a unique delivery protocol introduces a certain level of risk. From the perspective of the hospital bulk purchasers, the vulnerability introduced by sole-sourcing would be best dealt with by ensuring that a sole supplier of a product has alternate sources of raw materials and APIs, as well as back up manufacturing facilities. 3. Drug Shortages Web siteWe're looking forward to th[e] working group continuing to work and continuing to improve those Web sites so they become progressively more accurate. David Johnston, CAPDM, 27 March 2012 Witnesses commented frequently on the work of the drug shortages working group. Although witnesses were all supportive of the new national and bilingual Web site which provides information on drug shortages, several pointed out that it is funded and operated by the pharmaceutical industry and that drug companies are not obligated to post supply disruptions. Witnesses suggested that the two Web sites housed in Saskatchewan and Quebec do not supply sufficient information. Several witnesses, while supportive of efforts so far in

establishing a national drug shortages Web site, voiced a preference for

mandatory reporting.[9] They suggested that financial considerations prevented the pharmaceutical

manufacturers from acting on their moral responsibility to notify stakeholders

of supply disruptions as soon as possible. The Committee heard that the Minister of Health was encouraged that, in response to her letter seeking increased transparency about drug shortages, industry associations have clearly committed their members to public reporting of anticipated and actual shortages. In addition, reporting obligations can be made formally binding if purchasers of drugs, on behalf of provincial and territorial clients, embed this obligation in their supply contracts as well as a requirement that suppliers have contingency plans in place in the event that they are unable to fill orders. 4. Health Canada’s ProgramsIn order to identify and procure alternative medications, pharmacists consult Health Canada’s Drug Product Database...and Special Access Program. Myrella Roy, CSHP, 29 March 2012 As mentioned above, in Canada there is a regulatory requirement for manufacturers to notify Health Canada within 30 days of discontinuing the sale of a drug in this country. Health Canada can reflect this information on its Drug Product Database (DPD), which is a publicly accessible, searchable collection of information pertaining to drugs that have been approved in Canada and which have been identified by their manufacturers as being marketed in this country. The DPD includes each drug’s status — active or discontinued. The Committee heard that information regarding a drug’s status is not always accurate which can negatively affect the ability of health providers to identify alternative therapeutic options. Health Canada’s Special Access Programme (SAP) is designed to allow health providers access to drugs and medical devices that are not approved for sale in Canada. The SAP for drugs is intended to provide therapeutic options for individuals with serious or life-threatening conditions when conventional treatment is unavailable, unsuitable or has not been successful. Drug supply disruptions present just one of the situations for which the SAP has been created. The Committee was told that recent shortages have highlighted the need to modernize the SAP. It heard that the process is tedious and too time consuming. 5. Medically Necessary DrugsWhat we need is proactive planning to avoid any similar situation in the future. Joel Lexchin, individual, 3 April 2012 The Committee heard from a number of witnesses that critical, or medically necessary, drugs deemed to be essential and provided by only one or two suppliers should be identified and listed and their supply followed closely. It was suggested that a component of this list could be therapeutic options in the event of a supply disruption. Health providers emphasized that drug makers have a moral obligation to ensure a secure supply of critical medications. As such, some witnesses expressed a desire to see more regulatory or contractual requirements on the part of these suppliers to provide that security, recognizing this is provincial jurisdiction. 6. Drug Pricing and PoliciesPrices have been going down worldwide for some of these products, and therefore there are fewer companies that can commercially exist making those products. Jim Keon, CGPA, 27 March 2012 Pricing of patented pharmaceuticals is regulated by the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board (PMPRB). The PMPRB ensures that the prices of patented pharmaceuticals are not excessive. It accomplishes this by comparing the price of each medicine within seven other jurisdictions, namely: France, Germany, Italy, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Once a pharmaceutical comes off patent, generic versions of the product may be submitted to Health Canada for approval. Once approved, witnesses explained, there are two pricing systems for determining the price of generics that are regulated provincially; one for hospital pricing and a second for retail pharmacy pricing. Members were informed that the provinces and territories each have the responsibility of purchasing drugs and that it is done in isolation. The Committee was told that pharmaceuticals are purchased in bulk for hospitals, including generics whenever possible as these are less expensive than the brand name version. These bulk purchases are carried out by GPOs through the tendering process. This process is subject to provincial regulations on internal trade and competitive bidding. A second pricing system affects the retail pharmacy market. Provincial legislation may dictate restrictions on the prices charged for generic products listed on their formularies. For example, the Committee was told that Ontario’s pricing regulations have recently been amended and now require that the price of generics must be no more than 25% of the price of the brand name pharmaceutical equivalent. However, members were informed that provinces have some provisions for exception to this rule in instances where the cost of a retail pharmacy product is higher and that the price cap becomes too low and therefore discourages pharmaceutical companies from producing that drug. It also heard that Quebec’s regulations stipulate that it will not pay more for generics than any other province. Members were told that retail generic prices are internationally competitive and that around the world, prices of several generic drug products have fallen. As a result, fewer pharmaceutical companies produce those generics, which limits competition, favours sole-sourcing and reduces access to medicines. A ROLE FOR EVERYONEIndeed, the drug shortages issue demands attention and collaboration from everyone — we as innovators, generics, governments, health care professionals, and all others who play a role in providing medicines to Canadians. Russell Williams, Rx&D, 27 March 2012 Over the course of three meetings, members heard frequently that there are multiple players in the drug supply chain in Canada and that all stakeholders can play a role in helping to make the drug supply more secure. Health Canada is responsible for approving new drugs so they can be sold on the Canadian market and it acknowledged a backlog in the approval process for generic drugs. However, the Committee was told that recent changes to the user fees paid to Health Canada by drug companies for drug submissions have allowed the regulator to increase its resources and improve review times. As a result, Health Canada indicated that it is now able to process submissions for generic drugs faster and that a greater number of generic medicines will be approved for the Canadian market. The Committee heard, however, that provincial formularies may only list a single option, despite the availability of multiple generic versions. Unfortunately, provincial officials who were invited to testify before the Committee declined to appear. The Committee, therefore, did not hear from any provincial representatives in order to explore further the role of drug formularies or relevant pricing policies or tendering processes with respect to the security of the drug supply. In addition, members understand that the expedited review process of more than 40 submissions has now resulted in the approval of more than 20 drugs that may help to address current shortages, although the timeframe to get the newly approved drugs to market is unclear. Health officials also informed the Committee that Health Canada has approved 10 additional foreign sites to Sandoz’s list of approved sites for manufacturing and product testing for the Canadian market. Witnesses also spoke of Health Canada’s role with respect to requiring manufacturers to report when they discontinue the sale of a product in Canada and how this information and other information needs to be kept up to date on Health Canada’s DPD. The Committee heard about Health Canada’s responsibility for the SAP and officials indicated that the regulator had approved 59 requests to this program as a result of drug shortages. Health Canada officials informed the Committee that the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) operates a National Emergency Stockpile System (NESS) and that while the NESS was recently made available to the provinces in response to drug shortages, no requests had been received. Some witnesses spoke of the need for the federal government to be proactive on the global stage and the CPhA indicated that provinces and territories expect the federal government not only to relay the information gained in the international context but also to bring the concerns of the provinces and territories to the global forums. Some witnesses urged Health Canada to take the issue of drug shortages to the World Health Organization and the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development in order that the issue be thoroughly analyzed from an international perspective. Manufacturers suggested that they often can only source their raw materials and APIs from a single supplier, and cited falling prices as a primary cause of this. Low profit margins were also cited as the reason fewer companies produce some generic drugs, or that fewer facilities are available to manufacture them. Members heard from the brand name pharmaceutical industry that sole-sourcing practices in the post-patent context drives away competition, but did not indicate whether it endorsed policies among its member companies to be competitive with generics once their products come off patent. Some witnesses spoke of the moral responsibility of drug manufacturers to maintain production of critical or essential medicines. Companies must weigh this moral obligation against diminishing profits when deciding to bring generic drugs to the Canadian market. I actually think the government has played an important role in pushing us all together to come up with a solution. Russell Williams, Rx&D, 27 March 2012 The Committee also heard that the Minister of Health became quite concerned over a year ago about the global problem of increasing drug shortages, and wrote to industry associations, including CPhA, asking that they work together to explore ways of reducing future drug shortages and to improve transparency. This would improve notification within the health system in the event of a drug shortage and facilitate a response. The Committee also heard that drug manufacturers must globally shoulder much greater moral accountability for health care in Canada. A licence to make profits within the Canadian health care system should go hand in hand with a commitment to patient care in the form of a stable supply. Global drug manufacturers must ensure that any required remediation plans do not negatively affect, to a significant degree, the production of supply available in Canada. Bulk purchasers have indicated that their tendering practices will be modified in order to reduce the reliance on a single supplier. They suggested this can be accomplished either by awarding a contract for a back-up supplier, or by securing an obligation from the supplier that it has contingency plans should disruptions occur. The Committee notes that it heard testimony suggesting that suppliers may currently have contractual obligations with the bulk purchasers to meet supply quotas but that contractors may not be enforcing these terms. Wholesalers and distributors must also assume a role in securing the drug supply. The Committee heard that their umbrella organization, CAPDM, is on the drug shortages working group. In addition, members were told that CAPDM plays a critical role in the fair and equitable distribution of the drug supply. CADTH indicated a willingness to assume key responsibilities in a drug supply strategy for preventing and mitigating supply disruptions. The Committee heard that CADTH’s current role of assessing drugs that have been approved by Health Canada for their cost-effectiveness and providing listing recommendations to its participating federal/provincial/territorial formularies makes it well-suited for providing clinical advice on alternative medicines in the face of a shortage. CADTH also suggested that it would be capable of establishing a list of critical medications that have only one or two suppliers. Concerns over whether the pharmaceutical industry should be hosting the drug shortages Web site were addressed with the suggestion that CADTH might be a more appropriate choice. Finally, the Committee applauds the efforts of the end-users, both the health professionals and the patients. It recognizes the critical role played by these stakeholders and encourages them to stay engaged and remain vigilant. They supply an essential voice in the challenge to hold drug manufacturers to account. COMMITTEE RECOMMENDATIONSInformation about the problem of drug shortages is no substitute for fixing the problem of drug shortages. John Haggie, CMA, 29 March 2012 1. Essential Medicines and Therapeutic AlternativesThe Committee commends the establishment of the Multi-stakeholder Working Group on Drug Shortages and agrees that it is has been a positive first step in addressing the security of Canada’s drug supply. However, the Committee notes the concerns of some witnesses that a list of essential medicines should be established and that therapeutic options be identified. Therefore, the Committee recommends that: The Minister of Health in consultation with the provinces and territories, explore the possibility of the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health establishing a list of medicines supplied by only one or two companies and considered critical to medical care; and, The Minister of Health, in consultation with provinces and territories, request that the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health provide clinical information on the use of therapeutic alternatives. 2. ReportingThe Committee understands the concerns of those witnesses who urge mandatory reporting to the Web site rather than voluntary participation. However, it suggests that Health Canada’s role should be limited to monitoring discontinuances and that mandatory reporting for temporary disruptions can be better enforced at the provincial level or via contractual obligations through GPOs. With respect to sole-sourcing, members heard repeatedly that regardless of whether that is due to the tendering process, no alternative approved for sale in Canada, or a manufacturer having only a single supplier of raw materials or APIs, it is a practice that leaves Canadians vulnerable to supply disruptions. The Committee understands that all stakeholders have a role to play in order to minimize and eliminate, wherever possible, all sole-sourcing. Therefore, the Committee recommends that: Health Canada consider expanding the regulatory requirement for manufacturers to inform them within 30 days of discontinuing the sale of a product in Canada, to require that manufacturers provide advance notification of six months for planned discontinuances; and, The Minister of Health work with provincial and territorial counterparts to encourage Group Purchasing Organizations, drug plan operators or other holders of contractual agreements with pharmaceutical companies: · to include obligations for the drug company to report disruptions on the drug shortages Web site, and · to discourage single source strategies and to include requirements that suppliers have contingency plans in the event that they can no longer fill orders. 3. Pricing PoliciesThe Committee shares the concerns expressed by several witnesses regarding the lack of competitiveness within the generic drug industry due to the declining prices and low profit margins associated with these products. However, it did not hear sufficient testimony in this regard to draw any conclusions or propose solutions. While it acknowledges the limited authority the federal government has in this area, the Committee proposes that Health Canada take a leadership role in addressing this issue in the interest of advancing a national strategy. Therefore, the Committee recommends that: The Minister of Health encourage her provincial and territorial counterparts to initiate an examination of policies within their jurisdictions which affect drug pricing, including restrictions on generic pricing as well as tendering and contracting requirements, in order to determine the implications on drug supply. 4. Existing Federal ProgramsHealth Canada indicated that in addition to its role in drug approval, it is also responsible for maintaining the DPD and the SAP, both of which were referenced by stakeholders as being useful tools when navigating a drug shortage. However, it is necessary that the database be up to date and the SAP be as responsive as possible to the urgent needs that arise during these crises. The Committee is encouraged by the Department’s attention to its programs in this regard. The Committee notes that although PHAC announced that the NESS would be made available during this drug shortage, there does not seem to be a general policy regarding its use during shortages of critical drugs. Therefore, the Committee recommends that: The Public Health Agency of Canada develop a policy on the role of the National Emergency Stockpile System during shortages of essential medicines. 5. International PresenceSeveral witnesses emphasized that the issue of drug supply and the problem of drug shortages is global. The Committee agrees that the federal government must have a strong presence on the world stage to bring the concerns of stakeholders to international discussions. In this capacity, the federal government can share best practices, learn from other jurisdictions and bring new information back to share with provincial and territorial governments as well as professional organizations. Therefore, the Committee recommends that: The Minister of Health continue to cooperate with the World Health Organization and Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development to address the issue of drug shortages in order that the global causes of this problem and potential solutions can be examined. CONCLUSIONThe Committee acknowledges that multiple players are involved in the development of a pan-Canadian strategy to anticipate, mitigate and manage drug shortages and it commends the efforts to date of all those involved. Considering the increasing frequency and duration of drug shortages in recent years, the Committee expects to see a concentrated effort by all stakeholders in order that a comprehensive strategy be in place as soon as possible. [1] The six federal drug insurance plans are managed by: Health Canada (for eligible First Nations and Inuit individuals), Veterans Affairs Canada (eligible veterans), National Defence (members of the Canadian Forces), the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (eligible regular and retired members), Correctional Service of Canada (federal inmates) and Citizenship and Immigration Canada (eligible refugees and detainees of CIC). [2] Health Canada, 3 April 2012. [3] Ibid. [4] Ibid. [5] Ibid. [6] The Web site can be accessed at http://druginfo.usask.ca/healthcare_professional/drug_shortages.php. [7] The Web site can be accessed at http://vendredipm.wordpress.com/. [8] Canada’s Research-Based Pharmaceutical Companies, 27 March 2012. [9] Ordre des pharmaciens du Québec and Canadian Anesthesiologists’ Society, 29 March 2012; HealthPRO Procurement Services Inc., 27 March 2012; Canadian Epilepsy Alliance (written submission). |