FAAE Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

CANADA AND THE ARCTIC COUNCIL: AN AGENDA FOR REGIONAL LEADERSHIPINTRODUCTIONCanada has been a leader in multilateral cooperation in the Arctic region for over two decades. Soon after the end of the cold war, it argued that there was a need for a council that would unite the eight Arctic states and a number of indigenous peoples’ organizations to deal with common challenges, notably those related to the protection of the fragile Arctic environment. The Arctic Council was established from these discussions in 1996, and Canada served as its first chair. Following a full rotation among all member states, Canada will chair the council for the second time for a two-year term beginning in May 2013. After consultations in the Canadian north in the fall of 2012, the Government of Canada announced the broad theme — “development for the people of the north” — and sub-themes that it will pursue during its chairmanship. In anticipation of this important opportunity for Canadian regional leadership, the Committee conducted a study of Canada’s Arctic foreign policy, receiving testimony from over 40 witnesses, including federal departmental and territorial officials, academics, scientists and businesspeople. The present report summarizes the key findings from the Committee’s meetings in order to provide parliamentary input to Canada’s Arctic Council agenda and to identify what the Committee believes are the most pressing challenges facing Arctic states. One of the central messages to emerge from the Committee’s hearings is that the Arctic is opening to its nations and the world. It is equally clear that these developments are occurring at an accelerating pace, which raises significant diplomatic, regulatory, and practical questions for Canada and its Arctic Council partners. In other words, the management issues in the Arctic are both substantial and immediate. Witnesses emphasized the degree to which climate change, globalization and other processes are together resulting in opportunities and challenges in the Arctic that are qualitatively different from those that existed in 1996 when the Arctic Council was established. The Committee also heard that, if managed effectively, the global processes that are opening the region can contribute to increased prosperity and economic development for the people of the Arctic, including northern Canadians. The fact that the Arctic Council has a track record of producing studies that benefit from a combination of state resources and the knowledge of indigenous peoples’ organizations ensures that solid science and other technical work will be available to help guide future policies. The Arctic region is perhaps unique in the extent to which it blurs the lines between domestic and foreign policy. This report therefore outlines the main messages from the Committee’s testimony regarding issues that are relevant to both. The report concludes with the Committee’s recommendations for the steps that it believes Canada should take to enhance and further its own Arctic policies, as well as the priority initiatives the Committee believes Canada should pursue through regional and broader multilateral cooperation. THE ARCTIC AS A FOREIGN POLICY PRIORITYThe Arctic is increasingly being defined by three phenomena: globalization, global climate change, and global demand for natural resources. These three global trends have profound implications for the region’s environment and the people who reside there. The Arctic is also characterized by national pressures and opportunities. It is therefore increasingly important to both domestic and foreign policy. The fact that Canada will assume the rotating chair of the Arctic Council in May 2013, the regional organization mandated to address Arctic issues, has brought these issues into sharpened focus. The pace with which the Arctic is growing in the international consciousness is evident in the proliferation of media coverage, conferences, and publications in recent years. All of this debate has occurred alongside an increasing number of visits, announcements, strategies and undertakings by governments in their Arctic territories and in relation to Arctic issues. It is important at the outset of this report to understand why such a flurry of interest has taken hold. Put simply, the national and international stakes in the Arctic are high. It is a region rich in coveted natural resources, most of which have yet to be fully developed. It, along with the world’s other polar region in Antarctica, is on the front line of global climate change. It is a region where the implementation of the international legal framework governing the oceans is being carefully tested. It is the region that brings together the national and foreign policy interests of the world’s key late-twentieth century adversaries — the United States and Russia — with the aspirations and evolving policies of some of the world’s new twenty-first century powers, such as China and the European Union. It is a region that as a transit point represents potential savings in time and distance for companies that are increasingly in search of advantages in a competitive and integrated global economy. And, most importantly, all of these activities are occurring in a region that is notable for its unique geography and demographics. For example, approximately 500,000 of the 4 million people who live in the Arctic region are indigenous peoples,[1] the proportion of which is much higher in the Arctic territory of Greenland (88.1%), Canada (50.8%) and Alaska in the United States (15.6%).[2] Northerners are the stewards of what is at once a vast, forbidding, fragile, and beautiful territory and homeland. Jillian Stirk, Assistant Deputy Minister in Canada’s Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade (DFAIT), framed the urgency and relevance of developments in the Arctic for Canada, noting that “the north is undergoing rapid change, and this has sparked unprecedented international interest.” She added that change of this kind “presents both opportunities and challenges.”[3] Terry Hayden, Acting Deputy Minister for Economic Development in the Yukon Government, also suggested that Canada’s north is entering a critical phase. He told the Committee: “We are experiencing massive social, political, environmental, and economic change, and with that change comes the opportunity for benefits that reach beyond our northern borders.”[4] In his appearance, Bernard Funston, Chair of the Canadian Polar Commission, pointed out that many of the changes and forces that are affecting the Arctic are global in nature. He said: We have seven billion people on the planet at the moment, and it's not just a case that the things that will change the Arctic occur in the Arctic. Most of them, in fact, occur outside of the Arctic. Whether that's pressure for transportation routes, or minerals, or transboundary pollutants, or climate change itself, they're caused by non-Arctic drivers.[5] A traditional understanding of the foreign policy dimensions of the Arctic would make the case that there are five states with national borders in the Arctic Ocean; furthermore, relations exist between these states, who must manage the governance of waters, land, natural resources, and vessels in adjacent territory, all of which makes the Arctic the domain of foreign policy. While these facts remain the bedrock of international relations in the Arctic, it is the additional recognition of the truly global nature of the forces that are driving many of the most critical dynamics in the region — whether it is increased maritime traffic or resource exploration — that elevates the Arctic to a foreign policy priority for Canada. In response to this changing landscape, the Government of Canada released a Statement on Canada’s Arctic Foreign Policy in 2010, which expanded on the international dimensions of the government’s 2009 integrated Northern Strategy. The latter has four pillars:

The linkages between the two documents, which are presented by the government as a policy package, reflect the connection between the national and international dimensions of the Arctic. Canada’s foreign policy statement contains a broad vision of the Arctic as “a stable, rules-based region with clearly defined boundaries, dynamic economic growth and trade, vibrant Northern communities, and healthy and productive ecosystems.”[6] The document also acknowledges that “The geopolitical significance of the region and the implications for Canada have never been greater.”[7] THE ARCTIC COUNCIL AND CANADA, 2013–2015Canada has long been a leading Arctic state, both in terms of its domestic policies and with respect to multilateral cooperation in the region. A key element of Canada’s multilateral approach to the Arctic for almost two decades has been the Arctic Council. This unique body combines the resources and knowledge of the eight Arctic states — Canada, Denmark (Greenland), Finland, Iceland, Norway, the Russian Federation, Sweden and the United States — with those of six international indigenous peoples’ organizations for the benefit of cooperation on a common regional agenda. While that cooperation initially focused largely on the protection of the environment, it has since expanded to include issues such as sustainable development and emergency response. Canada served as the first chair of the Arctic Council from 1996–1998, and will do so again from 2013–2015. Canada’s Senior Arctic Official, Sigrid Anna Johnson of DFAIT, told the Committee: …you will be aware that the Prime Minister recently appointed the Honourable Leona Aglukkaq as minister for the Arctic Council and Canada's chair of the Arctic Council. …The appointment by the Prime Minister of a dedicated minister for the Arctic Council and of someone with such a deep understanding of Canada's north and its peoples reflects the importance the Government of Canada attaches to the north and to the work of the Arctic Council.[8] While the approach the Canadian government takes to the Arctic must inevitably evolve with changes in the opportunities and challenges that need to be addressed in that region, the unique nature and flexibility of the Arctic Council means that it remains as relevant to Canadian priorities today as it was when it was created. The Council — Then and NowThe possibility of real international cooperation in the Arctic began with the end of the cold war, when Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev called in a 1987 speech for a zone of peace in the region. Within several years, a Finnish-led initiative to unite the Arctic states and three Arctic indigenous peoples’ organizations to address a range of environmental issues led to an Arctic Environmental Protection Strategy (AEPS). In 1993, it was agreed to expand this strategy to include sustainable development, with Canada taking the lead in developing terms of reference and a work plan. Canada had, however, been arguing for several years about the need for the creation of a regional body with a broader scope and mandate. It was for this reason that Sara French, Program Director of the Munk-Gordon Arctic Security Program told the Committee: The genesis of the Arctic Council is largely found here in Canada. It was Canadians who built upon the Finnish initiative of the Arctic environmental protection strategy to push for a more permanent intergovernmental forum to facilitate cooperation among the eight Arctic states previously separated by the cold war boundaries.[9] Agreement was finally reached to establish the Arctic Council in 1996. In the Declaration on the Establishment of the Arctic Council (the “Ottawa Declaration”), ministers stated that:

Among other important elements, a footnote in the declaration stated that, “The Arctic Council should not deal with matters related to military security.”[10] The Arctic Council largely retained the structure of the AEPS, through the establishment of a number of working groups and the inclusion of Arctic indigenous peoples’ organizations as “permanent participants.” Funding for the council and the work of its project-driven working groups was to be provided on a voluntary basis by the eight member states. Coordination of work was to be overseen by regular meetings of Senior Arctic Officials of the states, supported by a secretariat that rotated with the chair of the council every two years. The six working groups of the Arctic Council, which are composed of researchers as well as governmental experts and officials, are the following:[11]

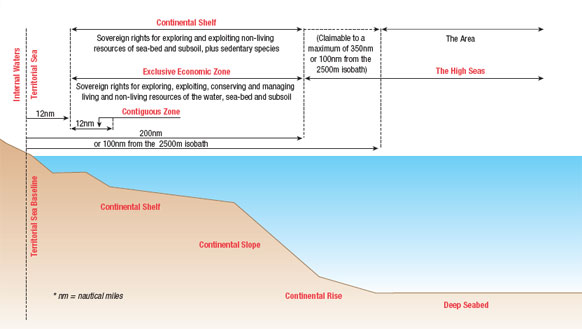

In addition to these groups, task forces are also created by ministers to work on specific initiatives. In the years since the establishment of the Arctic Council, its working groups have produced ground-breaking research, such as the Arctic Climate Impact Assessment (2004), the Arctic Human Development Report (2004), and the Arctic Marine Shipping Assessment (2009). While work related to scientific and other technical research has continued, Arctic states reached a new level of cooperation in 2011. In that year, they completed the Aeronautical and Maritime Search and Rescue (SAR) Agreement, the first legally binding agreement negotiated by the states under the auspices of the Arctic Council. Ms. Johnson of DFAIT argued that this development marked the evolution of the Arctic Council from “very much a scientific body” into a policy-making one. On the broader implications of these developments, she added that, “With the increasing attention on the circumpolar region, it's clear that this will be a role the council will rise to, to ensure that there is appropriate governance in the region.”[12] Organizational IssuesIn terms of the structure, working methods and focus of the Arctic Council, John Crump, Senior Advisor on Climate Change at the GRID-Arendal Polar Center, made the general observation to the Committee that “the world has changed much faster than the council.”[13] Adding to this sense of a changing regional landscape and new opportunities for regional leadership, Dr. David Hik, professor, Department of Biological Sciences at the University of Alberta, commented that since all the Arctic states have now had a chance to chair the Arctic Council, “This is a chance for the next cycle of chairmanships, with Canada being the first, to define some of these procedural issues and questions about the types of priorities we're going to place on questions that are within the purview of the Arctic Council.”[14] Recent years have seen a significant increase in the volume of work undertaken by the Council's working groups. Many projects and initiatives that are already underway — such as the updated Human Development Report — will be completed during Canada’s chairmanship. Despite this ever-increasing workload, however, beyond the establishment of a permanent secretariat in January 2013 there have been few changes to the internal operation of the Arctic Council itself since 1996. Inuit Circumpolar Council (Canada) President Duane Smith conveyed to the Committee his impression of “a body in its teenage years,” with respect to “how it conducts its business and activities.” Mr. Smith noted that as the Council “gets more grounded, and it has a permanent secretariat now, it's going to become much more active.”[15] Among other present challenges, Arctic Council states will in the coming months and years have to decide on the question of how to improve their support for the work of the Council’s permanent participants, as well as on the issue of the admission of permanent observers to the Council’s proceedings. More generally, Ms. Johnson told the Committee that during its chairmanship, Canada “will build on the council's continuing efforts to improve coordination across all of the council's working groups and task forces, and to improve tracking and reporting to effectively implement our work.”[16] Over the past six years, Norway, Denmark and Sweden have pursued a common agenda as chairs of the Arctic Council in order to enhance the coherency of the Council’s work and to allow for a longer time horizon to achieve their common goals. A number of witnesses likewise suggested that Canada should coordinate closely with the United States, which will succeed Canada as Arctic Council chair in 2015. On the question of coordinating chairmanships, Ms. Johnson stated that the Council is moving toward a “troika” system, in her words a “very effective” one in which the current chair cooperates closely with both the past and future ones. Canada has cooperated closely with Sweden, and she said that Canada “will certainly be working very closely with the Americans.”[17] The fact that Arctic states succeeded in negotiating a legally binding instrument under the auspices of the Council on search and rescue, and have now almost completed another one on marine oil pollution preparedness and response, has led some to argue that they should focus on the completion of such instruments. Michael Byers, professor and Canada Research Chair, Department of Political Science at the University of British Columbia, told the Committee that, in the context of climate change: We shouldn't think that these things can be done informally. We all know that when it comes to the most important issues in the world, countries negotiate binding treaties because they can be enforced. These issues are of such importance that we need to be talking about law-making.[18] Professor Whitney Lackenbauer, Associate Professor and Chair of the History Department at St. Jerome’s University, disagreed with the idea that legally binding instruments should be the goal and the marker of the Arctic Council’s success. He argued that “The desired goal is scientifically informed policy, most of which should be generated at the state level as per the original intent of the council. What this does is it allows policies to accommodate regional diversity, because there are different realities depending on where one lives or operates in the circumpolar world.”[19] Notwithstanding the Arctic Council’s many successes in the years since its establishment, maximizing its effectiveness requires recognizing what it can and cannot do. While it will remain the leading forum for dealing with truly regional issues, it cannot be expected to address effectively all issues — particularly global ones — that impact the Arctic, although it may be able to address their regional implications. In managing its foreign policy, the Government of Canada will therefore have to decide how best to balance its bilateral, regional and global efforts on various issues relevant to the circumpolar region. Setting an AgendaThe range of challenges that are facing the Arctic, and which could be pursued within the Council, is significant. Many of these were mentioned regularly during the Committee's hearings. They include maritime safety and ship standards, completion of an instrument on oil spill preparedness and response, implementation of the 2011 search and rescue agreement, and the possibility of fisheries management in the central Arctic Ocean. Following a series of consultations in the Canadian north and discussions elsewhere, the Government of Canada announced in the fall of 2012 that Canada’s overarching theme for its chairmanship of the Arctic Council would be “development for the people of the north.” Three sub-themes will address: responsible Arctic resource development, responsible and safe Arctic shipping, and sustainable circumpolar communities.[20] Issues brought forward in the Arctic Council often emphasize the links between domestic and foreign policy. Cooperation to address them in that multilateral setting allows for the sharing of knowledge and the identification of common approaches and best practices. For example, while building sustainable communities is an important domestic priority for the Government of Canada, Ms. Johnson noted that the same challenges are faced by states across the Arctic.[21] The fact that the Arctic Council works by consensus means that its priorities will be determined collectively. Mr. Funston, who was intimately involved with the Council from its establishment until 2010, told the Committee: … the priorities… are set in the Kiruna ministerial meeting in May 2013, and that will be done in collaboration with our Arctic state partners. The key here is the consensus rule within the Arctic Council, so Canada cannot unilaterally push an agenda, say, for sustainable development in communities in Canada's Arctic.[22] In his testimony, Duane Smith noted that, as of March 2013, the Government of Canada was “still consulting and working closely, not only with us but with others, in revising and trying to reflect everybody's views and perspectives, all while trying to also be realistic in the agenda and the mandate and the timeframe to ensure that we can achieve some objectives within that.”[23] The opportunities and challenges facing Canada and the Arctic Council on the eve of Canada assuming its chair were summarized by Andy Bevan, Acting Deputy Minister of Aboriginal Affairs and Intergovernmental Relations in the Government of the Northwest Territories. He said: Canada's upcoming chairpersonship of the Arctic Council presents a unique and exciting opportunity to advance its Arctic foreign policy. This is an important time for northerners, as economic growth and climate change are playing significant roles in the future of the Arctic. It is an opportunity to engage on northern priorities on both the national and international stage and to showcase the immense potential of Canada's north.[24] In the course of the Committee's meetings, a host of issues were raised by witnesses. These relate both to long-standing challenges and debates concerning the Arctic and to emerging ones that will be critical for states to address cooperatively during Canada's chairmanship and beyond. As noted, the Government of Canada has announced the overarching theme and sub-themes that will frame its chairmanship of the Arctic Council from 2013–2015. The scope and complexity of these themes and of the broader issues at stake in the region mean that additional consideration from a parliamentary perspective can only contribute to the objective of a successful chairmanship. In the sections that follow, the Committee will highlight the key findings and messages from the testimony it received in an effort to: clarify certain ideas about the Arctic; establish the challenges and opportunities facing that region; and lay out what the Committee believes are the most pressing issues that should be considered by Canada and the Arctic Council in the coming months and years. THE COMMITTEE’S KEY FINDINGSInternational Relations in the Arctic: Cooperation or Conflict?The first section of this report outlined the broad foreign policy context of the Arctic, making the case that the stakes for Arctic nations like Canada in the circumpolar region are high. However, the argument that there are significant opportunities and issues that need to be addressed in the Arctic does not mean that it is or will be an arena of conflict between states. Certain media reports and punditry on the Arctic in the last few years have created the impression of a “race for resources” in the Arctic, implying that the region is akin to a wild west-type environment where “claims” are either being staked out or are in flux, and where nations are engaged in stand-offs against one another in an effort to protect and assert their interests. Testimony given to the Committee suggests that such assessments of the Arctic are either misleading or overblown. Witnesses explained that there is no legal vacuum in the Arctic, and that, in fact, a robust legal framework governs Canada’s Arctic waters, which include the Northwest Passage, and the seabed beneath those waters, as well as the waters of the Arctic Ocean. Arctic states are pursuing their interests in accordance with that established legal framework. The International Legal FrameworkThe Committee heard from a number of experts on the international legal framework governing the Arctic, including Mr. Byers, Donald McRae, professor at the University of Ottawa, Alan Kessel, Legal Adviser to DFAIT, Ted McDorman, professor, faculty of law at the University of Victoria, who is currently seconded to the legal department at DFAIT, and David VanderZwaag, professor of law and Canada Research Chair in Ocean Law and Governance at Dalhousie University. These witnesses made fairly similar presentations with regard to the key legal principles that apply to Canadian Arctic waters and the Arctic Ocean. One of the key points that can be taken from all of these presentations is that Arctic waters, and the natural resources that lie within and underneath them, are no different than waters anywhere else on earth. They are governed by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), an international treaty that came into force in 1982. Some 165 states had ratified UNCLOS as of January 2013, including Canada, which ratified the treaty in 2003.[25] UNCLOS is a comprehensive international treaty. It defines different types of waters and state rights in those waters, and specifies the domestic laws and regulations that can govern each type, while also providing rules related to navigation, pollution control, and resource development. As depicted in Figure 1, key definitions related to the maritime zones of coastal states in the Arctic include states' "territorial sea," their "exclusive economic zones," their "continental shelves," and, beyond these, the "high seas." Figure 1 — Canada’s Maritime Zones

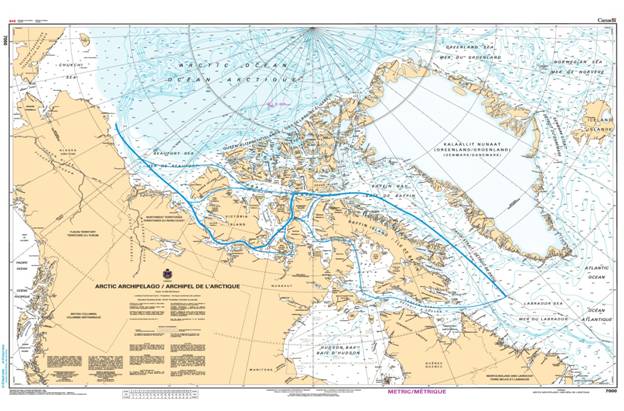

Source: Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Canada’s Ocean Estate – A Description of Canada’s Maritime Zones. On the first definition, waters up to 12 nautical miles from a state’s coastline constitute its territorial sea. All vessels enjoy “innocent passage” through the territorial sea of coastal states. Innocent passage is passage that “is not prejudicial to the peace, good order or security of the coastal State” (e.g. foreign ships cannot exercise weapons of any kind).[26] With respect to submarines, in the territorial sea of a coastal state, they "are required to navigate on the surface and to show their flag.”[27] States may adopt laws and regulations relating to innocent passage through their territorial sea. In the Arctic Ocean, as in all other oceans on earth, each coastal state is entitled to an exclusive economic zone (EEZ) that extends from 12 to 200 nautical miles from their coastline, adjacent to and beyond the state’s territorial sea. Within its EEZ, a coastal state has sovereign rights for the purpose of exploring and exploiting, conserving and managing the natural resources, whether living or non-living, of the waters superjacent to the seabed and of the seabed and its subsoil, and with regard to other activities for the economic exploitation and exploration of the zone…[.][28] Coastal states also have jurisdiction with regard to the protection and preservation of the marine environment in their EEZs. There is a specific and important Article (234) in UNCLOS pertaining to waters in ice-covered areas, which enables states to enforce "non-discriminatory laws and regulations for the prevention, reduction and control of marine pollution from vessels in ice-covered areas [...].” Canada exercises such jurisdiction in its Arctic EEZ in accordance with its Arctic Waters Pollution Prevention Act. Under UNCLOS, each coastal state is entitled to define its continental shelf, which comprises the seabed and subsoil of the areas “that extend beyond its territorial sea throughout the natural prolongation of its land territory to the outer edge of the continental margin,” up to a 200 nautical mile limit.[29] Each coastal state has certain sovereign rights over its continental shelf “for the purpose of exploring it and exploiting its natural resources.”[30] These resources “consist of the mineral and other non-living resources of the seabed and subsoil together with living organisms belonging to sedentary species…” (In general terms then, the provisions in UNCLOS related to the exploitation of natural resources contained in continental shelves apply to the physical land under the sea, but not the waters above). These rights are “exclusive in the sense that if the coastal State does not explore the continental shelf or exploit its natural resources, no one may undertake these activities without the express consent of the coastal State.”[31] Moreover, these rights “do not depend on occupation, effective or notional, or on any express proclamation.”[32] Coastal states also “have the exclusive right to authorize and regulate drilling on the continental shelf for all purposes.”[33] Professor McRae explained the legal significance of these key provisions of UNCLOS in respect to the delineation and exploitation of continental shelves as follows: These are rights that belong to the coastal state automatically and don't have to be claimed by the state. That's why the Russian flag-dropping incident of a few years ago, while amusing and scientifically interesting, was of no legal significance whatsoever, and the Russians themselves recognized that. Just as the states within the region cannot enhance their positions by making claims, rights over the continental shelf within the Arctic cannot be claimed by states from outside the region. The continental shelf, in legal terms, is the prolongation of the land territory. If you don't have any land in the area, then you cannot have a continental shelf.[34] Therefore, the popular narrative that there is a race underway between many states to stake maritime claims in the Arctic is misleading. Under certain circumstances, states can delineate a continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles if their shelf extends naturally beyond that point. The extension and outer limit of a state’s continental shelf must be based on a complex formula defined in UNCLOS. As the Department of Fisheries and Oceans explains, “Determination depends on the thickness of sedimentary rocks, which underlines the idea that the shelf is the natural extension of a state’s land territory.”[35] In order to establish the extent of its continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles to a maximum, under most circumstances, of 350 nautical miles, each “coastal state must submit scientific, technical and legal details...to the Commission on the limits of the Continental Shelf (the Commission).”[36] States have 10 years following the date of UNCLOS ratification to submit claims, which gives Canada until the end of 2013. Mr. Kessel pointed out that Canada's technical and scientific work is being done in cooperation with partners such as the United States and Denmark. He said that, "By the time we're finished, the land mass equivalent will be that of the three prairie provinces in terms of the extension, with, as you can imagine, extraordinary hydrocarbon potential and the like."[37] Even so, Professor McRae noted that there is a backlog in the Commission's work, and that "it may be 20 years before the commission will actually express its views on Canada's submission."[38] Mr. Kessel told the Committee that Canada will eventually define the outer limits of its continental shelf based on these recommendations. With respect to the possibility of state claims overlapping, he noted that "the extent and location of these overlaps is not yet known." Nevertheless, any such overlaps "will be resolved bilaterally in accordance with international law."[39] Professor McRae explained that the rules governing such disputes in maritime boundaries "are not very clear." But, "they have been developed in state practice and in the decisions of international tribunals."[40] With respect to the final pertinent definition under UNCLOS, which governs the wider Arctic Ocean, all seas beyond the outer limit of the territorial seas and EEZs of coastal states constitute the high seas. They are open to all states, which have freedom of navigation, overflight, fishing (subject to certain conditions) and scientific research.[41] Providing an overall picture of this mosaic of definitions, Mr. McDorman explained to the Committee that, "As with other oceans, the Arctic Ocean is simultaneously an area of exclusive national jurisdiction and an area of certain international rights exercisable by and available to all states."[42] James Manicom, Research Fellow at the Centre for International Governance Innovation, explained, for example, that the interest of East Asian states in the Arctic relates to the Arctic Ocean, or the high seas, not waters under national jurisdiction. The existence of an established legal framework in the Arctic, based on UNCLOS, and the desire of Arctic states to pursue cooperation in this field was underlined by the 2008 Ilulissat Declaration of the five Arctic Ocean states — Canada, the United States, Russia, Norway, and Denmark (Greenland). The foreign ministers recalled: ...that an extensive international legal framework applies to the Arctic.... Notably, the law of the sea provides for important rights and obligations concerning the delineation of the outer limits of the continental shelf, the protection of the marine environment, including ice-covered areas, freedom of navigation, marine scientific research, and other uses of the sea. We remain committed to this legal framework and to the orderly settlement of any possible overlapping claims.[43] The United States has not ratified UNCLOS; however, the United States does apply customary international law as regards the law of the sea. Professor McRae said that "The fact that the U.S. is not a party of the treaty is for the most part of no real significance."[44] The Committee believes that UNCLOS is of fundamental importance as an international legal framework. As Andrea Charron, Assistant Professor at the University of Manitoba, told the Committee: “UNCLOS is the most appropriate body of law to deal with oceans and seas.” She also reinforced the point that, “It is well respected, and the U.S., even though it hasn't ratified it, treats it as customary law.”[45] The Committee was therefore encouraged by the message received during its hearings that the Government of Canada is firmly committed to UNCLOS as the common basis for proceeding. Canada's Arctic SovereigntyWith UNCLOS as a reference point, witnesses also put forward many common points regarding the legal foundation of Canada’s Arctic sovereignty. Mr. Kessel made the overarching observation that "Canada's sovereignty over its lands and waters in the Arctic is long standing and well established."[46] With respect to Canada's land territory in the Arctic, witnesses agreed that no one disputes Canada's legal position. Mr. McDorman emphasized that, with the exception of the tiny Hans Island, Canada's Arctic territory "is unquestionably under Canadian sovereignty and not subject to any challenge by any other state."[47] The situation regarding the waters within Canada's Arctic archipelago is somewhat more complicated. Mr. Kessel told the Committee: No one disputes that the various waterways known as the Northwest Passage are Canadian waters. The issue is not about sovereignty over the waters or the islands; it's about the legal status of these waters and, consequently, the extent of control Canada can exercise over foreign navigation.[48] The United States maintains that the Northwest Passage constitutes an international strait for navigation.[49] However, Mr. Kessel stated: Canada's position is that these waters are internal waters by virtue of historic title and not an international strait. For greater clarity, Canada drew straight baselines around its Arctic islands in 1986. As a result, Canada has an unfettered right to regulate the Northwest Passage as it would land territory.[50] Mr. McDorman agreed, stating that "there is absolutely no question in international law that the waters, including the sea floor and all of the resources therein within the Arctic archipelago and the Northwest Passage, are Canadian."[51] Rather than being a dispute over “whether the Northwest Passage area is Canadian,” he described the dispute as being over the question of “how Canadian is the Northwest Passage? Is it like Wascana Lake in Regina or Halifax harbour…all Canadian for all purposes, in other words? That would be the Canadian view. Is it all Canadian but for a right of vessel navigation? That is the position asserted by the United States.”[52] With respect to the U.S. position, Mr. Kessel argued firmly that the Northwest Passage (see Figure 2) is not the same as the Straits of Malacca, Gibraltar or Hormuz. He noted that the Northwest Passage has never been used as an international strait for navigation, especially when considering that the Strait of Malacca could see 10,000 ships pass through it each year, and that until very recently the waters of the Northwest Passage were impassable. He stated: "You can't create a right out of something just because the nature of water changed from ice to liquid."[53] Furthermore, vessels that now enter Canadian Arctic waters enter with Canada's permission, the system for which will be discussed in a subsequent section of this report on maritime traffic. Mr. Kessel said that "We have been in control, and we've been strengthening that control over the period of time under question."[54] Figure 2 — Northwest Passage

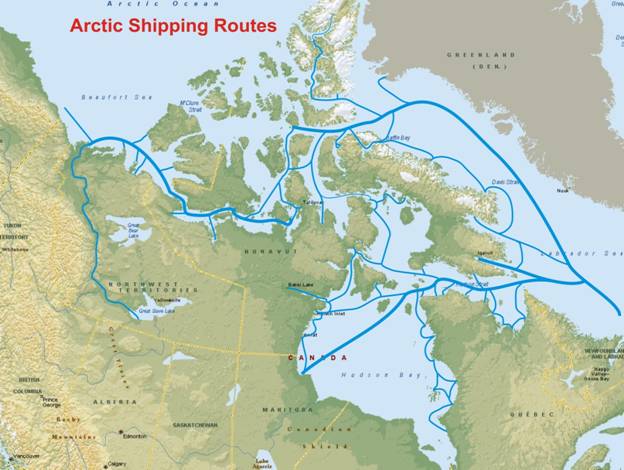

Source: Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Canadian Coast Guard, presentation to Committee, February 28, 2013. Despite the different positions held by Canada and the United States on the Northwest Passage, Professor McRae suggested that, in fact, the issue “is a matter of principle, not really a matter of practice.”[55] He noted that the U.S. “does not object in practice to the actual jurisdiction being exercised by Canada,” and that the central issue at stake for the United States is really a geopolitical concern over precedent regarding freedom of navigation; it “is more about the implications of Canada's position for other waterways around the world than concern about what Canada does or might do.”[56] There is a considerable amount of cooperation between Canada and the United States in the Arctic, notwithstanding this interpretative legal disagreement about the Northwest Passage. Within such a context, Mr. McRae argued “that Canada's position in respect of the Northwest Passage is best enhanced by simply going ahead with treating it and managing it as internal waters and retaining it as open to international navigation […].”[57] The actual enforcement of Canada's legal position could be an issue in the future, particularly given the predicted increase in maritime traffic in the Arctic and the resources that will be needed to monitor and respond to incidents related to such traffic. While emphasizing that Canada's sovereignty over its Arctic waters “is secure and is not under threat,” Shelagh Grant, Adjunct Professor in the Canadian Studies Department at Trent University, told the Committee: What may be at risk is Canada's ability to enforce its own laws and regulations in adjacent waters should increased ship traffic outpace investment in sufficient Coast Guard or patrol ships to respond to non-compliance with Canadian laws.[58] It is for this reason that Ms. Grant argued that investments in maritime infrastructure must be considered in addition to Canada's mandatory ship reporting technology, which is administered by the Coast Guard through the Northern Canada Vessel Traffic Services Zone (NORDREG). She told the Committee, “We're behind on infrastructure. We're ahead in technology.”[59] Resolving DisputesWitnesses before the Committee were clear that, while there are legal disputes in the Canadian Arctic, these do not amount to a sovereignty crisis. From the perspective of the Government of Canada, Mr. Kessel told the Committee that there are three disputes in the Arctic that Canada is concerned with:

Canada cooperates closely with other Arctic states — particularly the United States — in various endeavors in the Arctic, and Mr. Kessel stated that these three disputes “are well-managed and will be resolved peaceably in accordance with international law.”[60] On what Professor McRae called the “Lilliputian”[61] dispute over Hans Island, Mr. Kessel noted that the island claimed by both Canada and Denmark is 1.3 square kilometers, barren and uninhabited. He stated that this dispute has no implications for the waters or seabed surrounding the island, and that “regular bilateral discussions take place to move toward a mutually acceptable solution.”[62] In terms of the Lincoln Sea, while Canada and Denmark had agreed that the boundary between them should be an equidistant line, they disagreed on some technical aspects of how to draw it. Danish and Canadian technical experts have met informally to exchange information. Mr. Kessel stated that officials of both governments believe that such work “will provide a good basis to move forward on this dispute.” Shortly after Mr. Kessel's appearance before the Committee, on 28 November 2012, Canada and Denmark announced that they had reached a “tentative agreement” on the boundary in the Lincoln Sea.[63] On what Mr. Kessel called the “more interesting” question of the Beaufort Sea, he explained that the United States, “does not agree with Canada’s consistent and long-held position that the 1825 Treaty of St. Petersburg establishes the maritime boundary along the 141st meridian of longitude, resulting in a disputed maritime area measuring approximately 6,250 square nautical miles.”[64] He added that while both governments have offered oil and gas exploration licenses and leases in the disputed zone, neither country has allowed exploration or development in the area pending resolution of the dispute. Government experts from both countries have been engaged regularly as part of a dialogue over this dispute. Many Canadians probably believe that the most significant sovereignty issue in the Canadian Arctic relates to the waters of the Northwest Passage. As noted earlier, however, the issue in the Northwest Passage is not the sovereignty of the waters (which are Canadian), but their legal status. In regards to these three disputes, the Government of Canada will continue to pursue through diplomatic means its long-standing legal positions. The government argued in its 2010 Statement on Canada’s Arctic Foreign Policy that these disagreements are well managed, neither posing defence challenges for the country “nor diminishing Canada’s ability to collaborate and cooperate with its Arctic neighbours.”[65] Mr. McDorman similarly summarized the practical implications of these disputes as follows: …it is not the existence of the dispute that matters. Rather, it is whether the dispute is causing friction between the states involved. Using this standard, none of Canada's perceived Arctic disputes come close to a crisis level. More colourfully perhaps, whatever the causes of the loss of ice cover in the Arctic Ocean, it is not caused by the heat arising from Canada's international ocean law disputes.[66] Therefore, while exercising sovereignty will remain an ongoing and key element of Canada’s policies in the Arctic, fending off supposed challenges to that sovereignty need not be. At a more general level, witness testimony did not suggest that the Arctic will be an arena of inter-state conflict or unregulated competition in the near to medium future. When asked whether he predicted a future of cooperation or conflict in the Arctic region, Professor Lackenbauer told the Committee that he is “unambiguously expecting cooperation.”[67] Similarly, Mr. McDorman stated that in regards to ocean law, “there is a fair degree of bilateral and multilateral cooperation and, perhaps more important, common understanding amongst the Arctic states...”[68] Professor Lackenbauer argued that: …despite all of the media hoopla over this alleged “race for resources”, the simple fact remains that most of the Arctic's exploitable resources lie within clearly defined national jurisdictions. Conflict over Arctic resources remains highly unlikely, particularly in the North American part of the circumpolar world.[69] This view seems to be shared by the Canadian government. In reference to the 2008 Ilulissat Declaration cited above, Jillian Stirk of DFAIT told the Committee that “Canada recognizes that international cooperation strengthens our national efforts to address the opportunities and challenges emerging in the north.”[70] Professor Byers, who advised the then-Minister of Foreign Affairs, Lawrence Cannon, on Canada’s 2010 Arctic foreign policy document, told the Committee that even with the region's “Cold War history,” there is “little prospect of military conflict between nation-states.” He summarized the current Arctic landscape from the perspective of Canadian foreign policy as follows: …generally, it's a pretty positive scene: international cooperation, recognition of this by the Canadian government, and now, with our upcoming chairmanship of the Arctic Council, an opportunity to lead that cooperation further, to build on the government's Arctic foreign policy statement from two years ago. The challenges are enormous, obviously, and so too are the opportunities.[71] While there is concern over the growing interest of non-Arctic states in the circumpolar region, based on his research of East Asian foreign policy, Mr. Manicom told the Committee that East Asian scholars of Arctic politics also recognize the region’s geopolitics “as being largely cooperative.”[72] Professor Lackenbauer pointed out that, “International interest in a region doesn't mean that we should inherently feel threatened.”[73] Public Perceptions of the ArcticWitnesses before the Committee suggested that a disconnect exists to a certain extent between some of the key findings discussed above and public perceptions of those issues. Some suggested that the reality of Canada’s Arctic sovereignty has not always translated clearly into public discourse. The challenge posed by any discussion of sovereignty is that while the issue is essentially a legal one, the term is often used more generally by the media and others, with various connotations. Speaking against the background of Norway and Russia having settled a longstanding maritime boundary dispute peacefully in 2010, Mr. Funston told the Committee: Sovereignty is a very interesting proxy in Canadian policy for a whole range of things, domestic and international. There aren't many other Arctic states that actually have sovereignty crises, as we do from time to time. The Norwegians, for example, when they were dealing with the Russians on Svalbard, did not have a sovereignty crisis. They had an issue.[74] Professor Lackenbauer argued that Arctic sovereignty has been a long-standing preoccupation of the Canadian public, and therefore Canadian governments. He said: …historically the catalyst for our foreign policy interest in the Arctic has been a rather neurotic concern about sovereignty over anything else. We have a long history of perceiving sovereignty threats, particularly from the United States, followed by a brief surge of political interest and commitments to invest in our north. Then when the immediate crisis passes and Canadians realize sovereignty is not in clear and present danger, our usual track record is to lose interest in the north and fail to fulfill political promises. This time I hope, and I sense, it is different.[75] He also argued that there is a need to capitalize on the “intense” public interest in the Arctic and on improved government messaging regarding the region, as established in the 2009 Northern Strategy and 2010 foreign policy statement. In his words, “It's about messaging and consistency of message. It's about correcting some of the misinformation that's circulated…”[76] Witnesses cited several examples of public misperceptions about a range of issues in the Arctic. For example, in her appearance before the Committee, professor Charron opened her remarks by recalling a public event on the Arctic that had been held in Winnipeg the night before. She explained how this event, the themes it raised, and the viewpoints that were expressed by those in attendance illustrated the need for improved public messaging and education. She told the Committee that the event, …was extremely predictable in its message, both for what it did raise and for what it didn't raise. Four academics were asked to speak about the Arctic. There were themes that they did raise: there are opportunities in the north, but we must be very concerned about who has those opportunities; the U.S. is our greatest challenge; and our sovereignty is under threat. There were lots of maps … [which show] the potential conflict as a result of the continental shelf. What was not raised was Canada's actual northern strategy. There was no mention of the living conditions in the north. There was absolutely no mention of the Arctic Council or the fact that Canada will chair it. I might add that there was no mention of the Canadian chapter chairing the [Inuit Circumpolar Council] from 2014 to 2018.[77] From the perspective of economic development, Ms. Grant told the Committee, for example, that “Many Canadians are unaware of the degree of industrialization already taking place in the Arctic due to new mining developments and the associated ship traffic.”[78] For his part, Tom Paddon, President and Chief Executive Officer of Baffinland Iron Mines argued the need to “inject a fact-based narrative” into the public perception of resource development in the north.[79] In general, witnesses agreed that Canadians have an interest in and affinity for the Arctic. However, with respect to sovereignty issues and a host of others relevant to the Arctic and Canada’s Arctic policies, several underlined that there is a general need for increased public awareness. Such public education can ensure continued and informed support for Canadian domestic and foreign policies related to the region. The fact that southern Canadians may not know enough about their own Arctic makes it even more difficult for them to understand the complexity of the circumpolar Arctic, given the real differences that exist among the eight Arctic states in terms of geography, demographics, history, etc. Among other suggestions to increase knowledge about the north throughout Canada, Geoff Green, Founder and Executive Director of the Students on Ice Foundation, advocated the establishment in Ottawa of a “Polar House,” which he described as “a national centre to raise awareness about and to celebrate the past, present, and future of the Arctic.”[80] Karen Barnes, President of Yukon College, and Shelagh Grant of Trent University also supported this initiative. Ms. Grant even commented that, “The irony is that I was part of a committee, I think it was 25 years ago, when we first brought it up. ... We are the only Arctic country that does not have a polar centre or a polar house that would have a museum and resources associated. I couldn't encourage that…more.”[81] In terms of knowledge about the Arctic Council itself, Sara French of the Walter and Duncan Gordon Foundation told the Committee that in a poll released in January 2011 Canadians had scored significantly better than Americans in terms of their knowledge of the Arctic Council. This fact was little comfort, however, given that only one-third of Canadians in the three territories and 15% of southern Canadians were able to state clearly that they had heard of the organization. She therefore argued the need to raise awareness about the Arctic Council’s goals and programs, both within Canada and abroad. She added that it was also important that northerners were aware of the work underway at the Arctic Council and elsewhere, arguing that plain language summaries of often technical Arctic Council reports would be useful.[82] Bernard Funston and David Scott of the Canadian Polar Commission told the Committee that they and their colleagues had spent the past two years revitalizing the Commission, whose purpose, Mr. Scott explained, was “to be Canada's national institution for furthering polar knowledge and awareness.”[83] The goal of the commission is to aggregate polar knowledge, synthesize it and communicate it “to the general public, to the international community, and to decision-makers....”[84] Mr. Funston added his belief that as part of Canada’s upcoming chairmanship of the Arctic Council, there is a desire on the part of the government to increase understanding of these issues within Canada. He said: “I can see that it's really bringing home the Arctic Council's work in order for it to be better disseminated within Canada, and that is a role where the commission could assist.”[85] The Opening of the Arctic: Implications for Canada’s Foreign and Domestic PoliciesClimate ChangeAs was noted in the beginning of this report, recognition of the need to address environmental challenges in the Arctic provided the genesis for circumpolar cooperation. The initial regional mechanism that was developed, the 1991 Arctic Environmental Protection Strategy, became the basis for the broader work of the Arctic Council, which was founded in 1996. In 2000, that body then agreed to conduct a comprehensive arctic climate impact assessment. This report took 3 years to complete and involved over 300 researchers, indigenous representatives and other experts from 15 countries.[86] While more and up-to-date scientific information has been gathered in the years since this study was published, the general points from that comprehensive report continue to form the basis for discussions about environmental issues in the north, which witnesses argued is on the front line of climate change. Witnesses told the Committee that there are global connections to the climate change that is being experienced locally in the Arctic, and that the change occurring there has implications not only for the region, but the global system. In the first instance, these changes are having a disproportionate impact on the Arctic, which is affecting in a tangible way the daily lives of the people who live there and the local ecosystems. In the second, the climate change that is being seen in the Arctic is in turn shaping climatic events and forces in other parts of the world. Dr. David Hik, who is also the President of the International Arctic Science Committee, summarized the situation as follows: “I think the scientific consensus is that the Arctic is headed to a new state that will substantially change the north, and indeed the planet.”[87] With respect to the effect that climate change is having on the circumpolar region, and more specifically, the Canadian north, many witnesses spoke in personal terms and from direct experience. For example, Duane Smith, President of the Inuit Circumpolar Council (Canada), told the Committee: “With the changing Arctic, we're living on the edge, the frontier, if I may, in regard to the changes that are taking place. We're seeing it and living it first-hand.”[88] Dr. Barnes of Yukon College similarly said: “It is real. If you live up here, you see it constantly, and it’s facing people in terms of food security, transportation, and other issues like that.”[89] Andy Bevan, Acting Deputy Minister in the Northwest Territories’ Department of Aboriginal Affairs and Intergovernmental Relations, told the Committee: Temperatures are warming rapidly, coastal communities are facing increased coastal erosion, and the season for winter roads is shortening and becoming less predictable. Additionally, thawing permafrost is compromising transportation, buildings, and other infrastructure, and northern ecosystems are changing rapidly, which in turn is affecting traditional food security for many of our residents and communities.[90] In relation to all of these points, Stephen Mooney, Director of the Cold Climate Innovation Research Centre at Yukon College, went so far as to argue that, "For the northern communities the number one interest, I believe, is their concern about climate change, how the north is changing, and the way they can adapt."[91] Specialists in climate change and Arctic science also provided their perspective to the Committee. In addition to the dramatic sea ice melt that has been recorded in the Arctic, John Crump, Senior Advisor on Climate Change at the GRID-Arendal Polar Center, described an “increasingly green Arctic.” He told the Committee: Thirty years of satellite observations show the conditions today resemble those that were four degrees to six degrees of latitude further south in 1982; that's around 400 to 700 kilometres, depending on where you're measuring. Of course, habitat fragmentation, pollution, industrial development, overharvesting of wildlife, etc., are all having impacts at a regional and wider basis.[92] While debates about climate change in the Arctic tend to focus more on the waters and ice, which will be discussed in the next section of this report, Dr. Hik also pointed to significant land-based changes to the Arctic environment. He told the Committee that with decreasing snow levels and increasing temperatures, Arctic shrubs, which are able to grow faster, are increasingly appearing above the snow, thus darkening the surface and absorbing more sunlight, which would have previously been reflected by the snow and ice. He said: The second large change is a change in the seasonality of snow cover. Snow melting earlier in the season results in a higher albedo, a darker surface that absorbs more of the sun's solar energy. That ends up changing the depth of the active layer of permafrost, which can cause surface hydrology to change, that's the way streams and rivers and lakes are connected to each other on the frozen ground. All these things are cumulative and seem to establish a positive feedback. The process of warming accelerates as that land surface changes. It's occurring over a very large area. And because it's changed only within the last decade, we really haven't anticipated the consequences.[93] The accelerating change in the Arctic climate is reinforcing the need for Arctic Council countries to focus on adaptation measures for circumpolar residents and on steps to protect the fragile environment. A core element of the work that has been undertaken at the Arctic Council since 1996 relates exactly to environmental protection. One of the Council’s six working groups looks specifically at “protection of the Arctic Marine Environment,” while three others focus on monitoring threats to the Arctic environment and on work related to contaminants and conservation of Arctic flora and fauna. The fragile nature of the Arctic environment, and the need for northern economic development activities to engage in planning that takes these realities and environmental protection needs into consideration, was highlighted by Geoff Green. He used the example of a recent incident involving narwhal whales that migrate “out of summer feeding grounds in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago into Baffin Bay.” Those whales had been turned back from their intended destination “by seismic exploration.” The whales of course use echolocation in a quiet ocean to hunt and navigate. They became trapped at breathing holes in the channels of the islands until it was too late for them to reach open water, when the holes froze up. They starved, and they died. This kind of problem will likely increase as industrial activity increases, unless it's mitigated and studied properly. Certainly, the petroleum exploration people never intended to kill thousands of whales several hundred kilometres distant from their operations. It shows how in the Arctic, all activities, both human and natural, are connected. Even short-term activities can have long-term impacts.[94] Related to this need to protect the fragile Arctic environment, Professor VanderZwaag made a number of recommendations to the Committee related to shipping standards and pollution in the Arctic, as well as on management and governance issues related to the Arctic Ocean. As part of one of them, he noted the importance of ecosystem-based management and related work being conducted through the Arctic Council. But he argued that “we are a long way from putting in operation the ecosystem approach.” He noted more specifically that there is currently no “network of marine-protected areas” in place in the Arctic, “nor are we even close to it.”[95] Some witnesses suggested that the Arctic Council could play a greater role in addressing climate change, particularly with respect to concrete deliverables and outcomes. Michael Byers implied that what was needed was impetus and leadership. He told the Committee: My message to you on this is that the Arctic Council has been ready before to act in concert. It was prevented by [a U.S.] administration eight years ago that didn't realize the full impact and potential consequence of climate change. We know better today, across party lines, that [climate change] is a real problem, and the Arctic Council is a place.[96] Mr. Crump argued that the Arctic Council has to date not done enough follow-up work on its own ground-breaking 2004 regional climate impact assessment, which was noted above. In his opinion, this is an area toward which “Canada could make a major contribution.”[97] For his part, Mr. Bevan suggested that “there is a strong environmental agenda that can be championed not necessarily only through Canada's chairpersonship, but also through the future chairpersonship of the U.S.” Rather than being focused on policy areas like greenhouse gas reductions, which are the subject of international negotiations under the auspices of the United Nations, Mr. Bevan said that the emphasis in the Arctic Council could be on “environmental stewardship.”[98] Black CarbonA specific area that drew comments and recommendations from a number of witnesses relates to what are known as short-lived climate forcers, particularly black carbon. Witnesses noted that black carbon is both an environmental and a health concern. In basic terms, black carbon in most industrialized countries comes from the burning of diesel fuel in generators and trucks.[99] Diesel fuel is used ubiquitously in northern communities. The particulates (soot) generated by these activities, which are “heavier than air,” fall on the snow and ice and then act to absorb sunlight, accelerating the melting of the ice; hence the term “climate forcer.” As Professor Byers explained to the Committee, “The ice and the snow reflect 90% of the solar energy; the particulates absorb 90%.” Black carbon, thus, both accelerates and exacerbates “the larger climate changes resulting from other greenhouse gases.” In fact, he noted that some scientists “say that upwards of 40% or 50% of the snow and ice melt in the Arctic is the result of these particulates.”[100] Mr. Crump argued for action in this area, stating: While deep cuts in CO2 remain the backbone of efforts to limit the long-term consequences of climate change … rapid reductions in emissions of short-lived climate forcers such as black carbon and methane have been identified as perhaps the most effective strategy to slow warming and melting in the Arctic over the next few decades.[101] Professor Byers argued that there is need and room for enhanced cooperation and action within the Arctic Council on short-lived climate forcers such as black carbon and Arctic haze. Ms. Stirk of DFAIT informed the Committee that Canada has taken action in this area, as it “launched the Climate and Clean Air Coalition to Reduce Short-Lived Climate Pollutants in February 2012.”[102] (This coalition is a voluntary mechanism.[103]) Building on this initiative, Mr. Crump noted that “Canada’s Minister of the Arctic Council has said that Canada will advance work on short-lived climate forcers like black carbon." In his view, "This is an important statement.” Canada could expand on this initiative, he argued, by working in the Arctic Council to adopt “strong” measures, including the establishment of “a negotiating body on a circumpolar black carbon instrument to be adopted by the next ministerial meeting.”[104] With respect to the need for circumpolar cooperation to address black carbon, and the potential challenges and resistance that could be encountered in doing so, Professor Byers drew an analogy with Canada–U.S. cooperation in the late 1980s and early 1990s on acid rain, which he argued had elicited “similar concerns” in the countries concerned during initial discussions over whether and what remedial actions should be taken. Mr. Crump also noted an important Canadian precedent on an earlier environmental mechanism, as an example of what could be accomplished in the months and years ahead: In the 1990s, Canadian data assembled through the national contaminants program, combined with the moral force of the Arctic indigenous peoples and the desire of all Arctic states to participate, contributed to the negotiation and signing of the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants. This was the first international environmental instrument that actually banned toxic substances and it is seen as a major precedent. This was the result of sound research and the alliance of indigenous peoples' organizations and Arctic states, something that's always possible at the Arctic Council. It led to an important step forward in global environmental governance.[105] Returning to the current issue of potential efforts to reduce and mitigate the effects of black carbon, Mr. Crump stated that "It's important that the Arctic Council be seen to be in the forefront of this work."[106] Scientific Research and CooperationWitnesses drew the connection between the need to address climate change and related adaptation and environmental protection in the Arctic, and scientific research. Professor Byers told the Committee that, …the Arctic is changing so very quickly that it is imperative that we have the very best science possible on all these issues, and this science should be exercised and dealt with in terms of its recommendations and consequences in concert with other countries.[107] One of the recommendations put forward by Dr. Anita Dey Nuttall, Associate Director at the University of Alberta's Canadian Circumpolar Institute, pertained to the "need for Canada to have an overarching arctic-northern science policy,” while she also noted “the potential of using science diplomacy as a tool for Canada's arctic foreign policy."[108] Danielle Labonté, Director General of the Northern Policy and Science Integration Branch in Aboriginal and Northern Affairs Canada, also highlighted “the foundational role of Arctic science.” She drew the Committee’s attention to two new initiatives. The first is the Canadian High Arctic Research Station, which “will be a year-round facility, in Cambridge Bay, Nunavut.” This research station “will advance Canada's knowledge of the Arctic in order to improve economic opportunities, environmental stewardship, and the quality of life for northerners and all Canadians.” The second is the Beaufort regional environmental assessment, which is a four-year partnership between different levels of government, Inuit communities, academia and industry, which aims “to develop a knowledge base of scientific and socio-economic information in advance of oil and gas development so as to inform the decision-makers of the region…”[109] Referring to the Government of Canada’s 2009 Northern Strategy, Dr. Hik told the Committee that “the underlying support of the four pillars is science and technology, what once was called the “one ring that binds them all”.” He therefore expressed his optimism “that we have capacity. We just need to make sure we focus that.”[110] Drawing the Committee’s attention to initiatives underway in the United States, including their five-year inter-agency research plan related to scientific research, Dr. Hik also suggested that enhanced “bilateral scientific cooperation” might be possible in the “context of the upcoming Canadian and U.S. chairs of the Arctic Council.”[111] Maritime Traffic in Canada’s Arctic Waters and the Arctic OceanAs discussed, climate change has significant consequences for the Arctic, not the least of which is the reduction in sea ice cover and extension of ice-free periods. Along with other factors, these changes are opening Canada's north to considerable natural resource development. For these reasons, and the fact that Canada has an extremely long Arctic coastline, it has to prepare to manage increased maritime traffic in its Arctic waters and to consider the implications of increased vessel activity in the international Arctic Ocean beyond its waters. As part of these management efforts, two areas that require Canada's attention are ship standards and safety regulations, and search and rescue capabilities. On the first issue — regulations — there is a need for continued enforcement of Canada's established legal regime in its Arctic waters and for the conclusion of a robust and mandatory polar code to govern the Arctic Ocean. This reality has been reflected in Canada’s stated priority sub-themes for its upcoming chairmanship of the Arctic Council, one of which is "responsible and safe shipping." On the second key issue, now that Arctic Council states have taken the important step of reaching a binding agreement on search and rescue, the focus must shift to implementation, which will necessitate significant Canadian resources. There is evidence that Arctic sea ice is shrinking and thinning and that both of these effects are accelerating. From the pan-Arctic perspective, in September 2012, scientists from the National Snow and Ice Data Center, which is based in Boulder, Colorado, announced that Arctic sea ice had melted to what was likely “its minimum extent for the year on 16 September,” a level which was also “the lowest summer minimum extent in the satellite record.”[112] Two months later, the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) issued its provisional statement on the state of the global climate in 2012. The statement concluded that not only had the low recorded on September 16th broken “the previous record low set on September 18th, 2007 by 18 percent,” it was also “49 percent or nearly 3.3 million square kilometres below the 1979–2000 average minimum.”[113] The WMO statement also commented: “The difference between the maximum Arctic sea ice extent on March 20th, 2012 and the lowest minimum extent on September 16th was 11.83 million square kilometres — the largest seasonal ice extent loss in the 34-year satellite record.”[114] From the Canadian perspective, Environment Canada reported that: “In Northern Canadian Waters, during summer 2012, minimum ice coverage of 8.4% was recorded for the week of September 10, breaking the previous Canadian Arctic record set in 2011 (9.4%).”[115] Perhaps the most profound implication for the Arctic of the decline in sea ice is the predicted increase in maritime traffic in the region. Professor Byers impressed upon the Committee the rate at which the climate in the Arctic is changing, and the corollary effect the pace and extent of these changes is having on related predictions of activity in the area. He told the Committee: I remember six or seven years ago, when I was warning that we might see seasonally ice-free waters through the Northwest Passage, I was assured by very many people, including a number of distinguished scientists, that my concerns were overblown and that we wouldn't actually see any significant melt-out of the Arctic Ocean ice pack until at least 2050, and probably not until 2100. The leading scientists are now predicting that we could see a total late-summer melt of Arctic sea ice as early as 2015 to 2020. That is truly astounding—not only for what it says about the pace of climate change, but also for the consequences. […][116] The fact that Arctic waters are predicted to be more accessible sooner is significant because of what that means for access and maritime traffic. New Shipping RoutesAs has been documented in numerous reports, what is commonly referred to as the “Arctic” — a general expression which in the context of maritime traffic typically can include the Northwest Passage through Canadian waters, the Northern Sea Route (or Northeast Passage) through Russian waters, or the Polar Route through the Arctic Ocean — represents a potential saving on time and distance for maritime transits between Europe and Asia. The argument that is put forward on the basis of this fact is as follows: Arctic ice is diminishing, the various Arctic routes are shorter than traditional shipping routes, and resource development projects are proliferating in the circumpolar north; therefore, commercial maritime traffic in the Arctic will increase substantially. In one high-profile demonstration of the degree to which the circumpolar region could be an arena of international commercial activity in the future, August–September 2012 saw the icebreaker vessel, the Snow Dragon (Xuelong), become the first from China to cross the Arctic Ocean. (As part of the same two-way journey, it also sailed the Northern Sea Route between the Pacific and Atlantic oceans.)[117] Ms. Grant told the Committee: “The transit across the Arctic Ocean by China's conventional icebreaker last summer was likely a harbinger of what is to come: icebreakers creating a path for a convoy of bulk carriers.”[118] The combination of changes in the international market for natural gas and the increased melting of polar ice also resulted in another first in November 2012. In that month, the gas tanker ship Ob River, which had been constructed with a view to shipping gas west to North America, instead set sail from Norway through the Northern Sea Route to Japan, the first ship of its kind to do so in the winter.[119] Most recently, a study published by researchers at the University of California in January 2013 analyzed climate model projections of sea ice to study potential new trans-Arctic shipping routes linking the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. On the basis on their findings, they argue that “by mid-century, changing sea ice conditions [will] enable expanded September navigability” for “open-water ships crossing the Arctic along the Northern Sea Route …, robust new routes for moderately ice-strengthened…ships over the North Pole, and new routes through the Northwest Passage for both vessel classes.”[120] Even so, with specific respect to the situation in Canada’s Arctic waters, the Committee heard a fairly sober assessment of current and predicted trends in activity from experts. Maritime traffic in the Northwest Passage did increase by 29.2% from 2011 to 2012 when there were 31 total transits. However, it is important to underscore that 23 of those transits were done by “pleasure craft,” with the remaining activity attributable to cruise ships, government vessels, tugs, barges, tankers and research vessels.[121] Many witnesses cautioned that the reduction in ice cover in the broader Arctic region will not necessarily lead to a rapid increase in shipping activity through the Northwest Passage in the near term (see Figure 3). Those waters remain hazardous to vessels. Moreover, diminished ice does not mean an absence of ice, and the changing ice patterns and composition of that ice are in some ways making the waters less predictable for vessels. On this issue, Laureen Kinney, Associate Assistant Deputy Minister with the Department of Transport, told the Committee: The potential is huge, but the actuality is quite slow. I think it's important to also reinforce the point that was made earlier. The risk is so substantial in terms of unpredictability, with these more open areas and with climate change impacts. The risk is actually more undefined, so there is a significant impact on insurance and the capability of the vessels that want to operate in these areas to do so with sufficient liability insurance, etc.[122] In the words of the Coast Guard’s Deputy Commissioner for Operations, Jody Thomas, “There is a romanticism about the Northwest Passage. It promises quicker transit from east to west. The reality is it remains treacherous and dangerous as the ice continues to break away and float south.”[123] Ms. Thomas also pointed out that the break-up in the ice has actually caused it to move south into the Northwest Passage, which has made those waters “inherently more dangerous.” She told the Committee: Last summer, for example, there was significantly more ice in the Northwest Passage and in Frobisher Bay it was iced in for quite some time due to the winds and the breakup of the ice. Therefore, the need for icebreakers is actually increasing as the Arctic ice breaks up. It is not less dangerous.[124] Not counting the need for refits at a given time, the Canadian Coast Guard has seven icebreakers available for the Arctic in the summer months, one of which is dedicated to scientific work.[125] The fleet is being renewed, and Canada is planning to have its first polar icebreaker, the John G. Diefenbaker, available to replace its current heavy icebreaker, the Louis S. St. Laurent, by late 2017. Ms. Thomas told the Committee that this new icebreaker “will provide the coast guard with greater range capability and accessibility over the entire year in the Arctic, which is important as the shipping season extends and the breakup of ice is found in non-traditional areas.”[126] Figure 3 — Shipping Routes in Canada’s Northwest Passage