FAAE Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

THE HUMAN RIGHTS SITUATION IN BURMA: CONCERNSWhile the Subcommittee welcomes recent political reforms in Burma, we believe that we must remain realistic about the rate and extent of change. There are still many obstacles to democracy in Burma and the political situation remains fragile. As Mr. Din stated on behalf of the U.S. Campaign for Burma, “[t]o be sure, there have been significant changes in Burma over the past nine months, but it would be a mistake to assume that they are irreversible or that all things are pointing in a positive direction.”[87] Similarly, Mr. Davis told the Subcommittee: “[w]hile these changes are important, the same problems that have plagued the people of Burma for decades, including rampant forced labour, attacks on civilians, the use of land mines, and lasting impunity for those who commit heinous human rights violations, continue to this day.”[88] The Subcommittee, therefore, wishes to draw attention to a number of very serious concerns about the lack of respect for universal human rights in the country, in particular in ethnic minority areas. A. Concerns with Respect to Civil and Political Rights1. Persistent Weakness in Governance StructuresIn February 2008, a committee appointed by the military junta completed the drafting of a new constitution, which was adopted in May 2008 in a widely criticized national referendum. The constitution entrenches military control over government in Burma and has been critiqued by international human rights organizations for failing to protect key human rights.[89] a. The Need for Constitutional Reform(i) Lack of Civilian Control of the MilitaryWitnesses told the Subcommittee that at least 25% of seats in both houses of Parliament are reserved for active service members appointed by the Commander-in-Chief of the Defence Services. Key cabinet portfolios such as defence, home, and border affairs are also reserved for active service military personnel. Members were dismayed to learn that appointments to these three powerful ministerial portfolios are controlled not by the civilian President, but by the Commander-in-Chief of the Burmese military.[90] In addition to these formal guarantees of military representation in parliament, Mr. Humphries pointed out that in the Burmese Union legislature, “out of the 600 seats, probably 550 of those seats are maintained by previous military or military.”[91] Witnesses stressed that the 2008 constitution contains a number of provisions that limit democratic governance in Burma. For example, the constitution entrenches the leadership role of the military in national political affairs, assigns the military the responsibility for safeguarding the constitution, and explicitly permits the Commander-in-Chief of the Defence Services to take all sovereign power in order to counter violence or insurgency, as well as other threats to national disintegration or disintegration of national solidarity.[92] Although the President holds the formal power to declare a state of emergency under the constitution, this may only be done following “coordination” with the military-controlled National Defence and Security Council. A nation-wide state of emergency can only come to an end once the Commander-in-Chief reports to the President that he has accomplished his duty to counter the threats that led to the declaration of the state of emergency. The constitution also gives the military the power to manage the transition back to civilian rule.[93] Thus, the President’s power to determine whether a state of emergency ought to be declared and when it ought to end appears to be subject to a high degree of military influence. Moreover, there is no possibility for effective parliamentary or judicial scrutiny of the declaration of a nation-wide state of emergency or the actions taken by the military while a state of emergency is in force.[94] Indeed, witnesses consistently told us that the real power to declare a national state of emergency, which transfers sovereign power to the military, lies with the Commander-in-Chief.[95] We were also told that the constitution does not contain any provision for the removal from office of the Commander-in-Chief,[96] in contrast to the situation of the President and members of the judiciary.[97] Witnesses consistently testified that these provisions, taken together, “grant supreme power into the hands of the military.”[98] Thus, as Mr. Giokas told us, “the civilian government doesn't necessarily control the military.”[99] The persistent refusal of the Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces, Vice Senior General Min Aung Hlaing, to obey the President’s order to halt the military offensive in Kachin State, was cited by a number of witnesses as clear evidence of this lack of civilian control.[100] International human rights bodies have emphasized that in countries transitioning to democracy, it is essential to have a clear legal framework limiting and specifying the role of the armed forces and providing for effective political and civilian control over them.[101] The Subcommittee believes that civilian control over the military is critically important if the Burmese government’s current democratic reforms are to be sustained, expanded and entrenched. In our view, promoting effective civilian control of the military ought to be a key priority for Canada in its bilateral relations with Burma. (ii) Undue Restrictions on Political and Democratic RightsIn addition to the formal entrenchment of military power under the 2008 Burmese constitution, witnesses drew our attention to significant limitations on political participation and democratic rights contained in the document that undermine genuine democratic governance. The constitution, according to Mr. Humphries, gives a lot of freedoms and rights in words, but none of this is carried out. … For example, they say they have freedom of religion, but my wife as a minister and my friend as a pastor cannot vote. How is that a democracy when you can't vote? In addition to being denied their right to vote, religious leaders cannot be part of a local political party, and cannot apply for government office.[102] The right to run for office is also denied to individuals who are members of organizations that obtain or directly or indirectly use funds, land, housing, or other property from a religious organization, government or other organization of a foreign country, potentially disqualifying any individual affiliated with a religious community or secular civil society organization that receives foreign support — which would include many groups working to improve human rights conditions in Burma. Individuals who have been convicted of “an offence relating to disqualification” for election are also barred from running for office, potentially disqualifying former political prisoners.[103] The formation of political parties is also restricted by the constitution. All political parties are required to be loyal to the state and to hold the objective of maintaining national sovereignty and the Union of Burma.[104] The potential significance of such a provision is illustrated by the previous military junta’s reported justification of the detention of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi partly on the basis that she had acted with the intention of weakening the integrity of the nation.[105] The constitution also disallows political parties that have been declared “unlawful associations” under existing law, as well as those “directly or indirectly” involved with insurgent groups or unlawful associations, and any political parties that receive assistance from religious associations.[106] It is in this context that Mrs. Humphries told the Subcommittee that the 2008 Burmese constitution is built to suit the needs of the military and to protect them.[107] The Subcommittee notes that opposition to oppressive military rule in Burma has traditionally been led by student dissidents, monks, ethnic leaders, and ethnic minority religious communities, as well as by organizations based abroad that advocate and work for human rights in Burma, supported by foreign funding. We observe also that over the last 60 years, Burma has enacted multiple laws aimed at crushing political dissent and the formation of civil society groups, making any prohibition on political parties that have been declared unlawful under present legislation extremely suspect. In addition, many of the largest ethnic minority groups have been at war with the central government for decades over issues related to autonomy and power-sharing, during which time they have created political parties to advocate in favour of their collective aspirations. We were told that only those ethnic leaders who were perceived as favourable to the ruling party and the military were allowed to form political parties to contest elections. Mr. Davis explained that during the 2010 election most of [the Kachin] political parties were banned from running, and even in the election in April, two Kachin political parties were not allowed to contest. They're pushing for fundamental changes to the 2008 constitution so that they can have more representation, and the Burmese are not agreeing to this at all right now.[108] In the end, the by-elections held in April 2012 were cancelled in Kachin State due to armed hostilities commenced by the Burmese military against the Kachin Independence Army, which continued despite the President’s repeated orders to cease the fighting.[109] Mr. Humphries summed up the situation in these words: They say in the constitution that anyone can put together a party, but when [the political representatives of the Kachin people] put up parties to be part of the government system, they disallow them. They say you have the freedom to vote, but then they turn around whenever it's convenient and remove that freedom. The constitution allows them to do that. In the Subcommittee’s view, the constitutional provisions discussed above restrict democratic rights and freedoms in a manner that is inconsistent with international human rights standards. The Subcommittee is particularly concerned that the Burmese constitution formally discriminates against religious leaders in the exercise of their democratic rights and, in practice, does not permit equal access to democratic and political rights for many ethnic minority groups.[110] We believe that this situation is likely to impede Burma’s successful transition to democracy in the long-term and we hope that all parties in the Burmese legislature will come to see the importance of undertaking a process of constitutional change. (iii) Challenges to Constitutional ReformAs a result of the flaws in the Burmese constitution, Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and the NLD have identified constitutional change as a key plank in their political platform. However, a proposal to amend the Burmese constitution requires that 20% of legislators submit a bill for consideration to a joint session of both houses of the Union of Myanmar Parliament. The Subcommittee was very concerned to learn that approval of any constitutional change requires approval by more than 75% of the members of both houses of Parliament, which means in practice that even if all of the elected, civilian MPs vote for constitutional change, the military can still block any reform.[111] Mr. Davis told members that it was unrealistic to expect constitutional change to come quickly to Burma, stressing that it will likely take some time to persuade some appointed military legislators that voting for constitutional change will bring important, positive effects.[112] Mr. Humphries, however, told us that people in Burma are generally positive about the prospects for constitutional change in the long term.[113] Mr. Giokas told the Subcommittee that constitutional change in Burma is primarily a domestic issue, “but if they’re going to develop a functioning democracy, they’re going to have to deal with these things in a democratic fashion.”[114] The Subcommittee agrees with this assessment. 2. Absence of the Rule of LawAchieving the constitutional reforms necessary to entrench and sustain democratic governance in Burma will be a long-term project. In the shorter-term, however, there is significant work to be done to establish the rule of law in the country. At the outset, the Subcommittee wishes to acknowledge that the Burmese government has expressed a desire to improve the rule of law in Burma and is taking steps towards this goal, including through the establishment of a parliamentary committee on the rule of law. Nevertheless, the Subcommittee wishes to highlight its concerns regarding the near absence of the rule of law in Burma at the present time. Progress towards reforming legislation that does not conform to international human rights standards, towards establishing both substantive and procedural legal, judicial, and administrative guarantees of due process and accountability, and towards reforming the police force ought to be included in discussions by Canada and other countries in assessing whether to permanently lift remaining sanctions in the future. a. The Urgent Need for Legal ReformMr. Giokas emphasized that Canada remains concerned about the consistency of certain Burmese laws with international human rights standards. He referred us to the reports of the Special Rapporteur on human rights in Myanmar, who has expressed the view that a number of Burmese laws enacted under the military dictatorship still impermissibly limit the enjoyment of human rights.[115] In particular, Mr. Quintana has stressed that international human rights standards require any legal limitations on human rights to be clearly defined by law, imposed for a specific and legitimate purpose, and be necessary and proportionate in the context of achieving such purposes in a democratic society. Vague, broad and sweeping formulas for limiting human rights, in his view, “contravene the principle of legality and international human rights law.”[116] In his March 2012 report, the Special Rapporteur stated that Burma needs to accelerate its legal reform process and recommended that the government establish clear, time-bound target dates for the conclusion of the legislative review.[117] b. Inadequate InstitutionsWitnesses consistently told the Subcommittee that key institutions necessary to the maintenance of the rule of law in Burma were exceptionally weak, lacking the professional capacity and legal framework to perform their functions. (i) The JudiciaryWitnesses flagged reform of the judiciary as another significant challenge that Burma needs to address in order to establish the rule of law in the country.[118] In practice, the Subcommittee heard that individuals do not have the opportunity to defend themselves fully against criminal charges in a court of law or to seek judicial redress when their property is taken from them unlawfully.[119] Mr. Din told the Subcommittee that “[c]orrupt judges run the courts without due process and make rulings as instructed by their superiors, or in favour of those who pay the most.”[120] Mr. Davis reiterated this view, telling us that the Burmese judiciary is not independent from the rest of government and that institutional change will be a long-term project, requiring significant support and judicial education.[121] In addition, the Subcommittee was particularly dismayed to learn that the Burmese military “is not subject to any institutional accountability mechanism that could be used to punish or deter crimes.”[122] Indeed, the Commander-in-Chief administers the military justice system free from any civilian oversight and acts as the final appellate authority.[123] The Subcommittee wishes to stress that international human rights standards place a high value on judicial impartiality and independence, which are necessary to ensure the right to equality before the law, the right to a fair hearing before a court of law, the right to judicial review of the legality of detention, and the fair trial rights of defendants in criminal cases such as the presumption of innocence and the right to make full answer and defence. An independent and impartial judiciary is also a crucial check on the abusive use of power by other branches of government and organs of the state, including the military.[124] Effective access to competent, independent and impartial justice is necessary to ensure that those whose rights have been violated receive redress, and is vital to combating impunity.[125] The Subcommittee notes that effective access to justice is fundamentally compromised when the military chain of command has final, unfettered discretionary authority over the disposition of any complaints or legal charges. Mr. Davis identified the establishment of an independent judiciary as a crucial step to ensure that the economic benefits of reform reach the population of Burma.[126]As Burma opens its economy and adopts market reforms, it can be expected that there will be an increase in business-related disputes. If economic reforms are to succeed, the Subcommittee believes that these disputes eventually will need to be adjudicated within a sound legal framework by an independent and impartial judiciary in which both foreign investors and domestic actors can have confidence. The Subcommittee stresses that the establishment and preservation of an independent and impartial judiciary in Burma must extend to states of emergency.[127]We wish to highlight our deep concern over the provisions of the Burmese constitution that permit, during a state of national emergency, the transfer of all judicial powers to the Commander-in-Chief and the suspension of important procedural guarantees that Burma is bound to respect under international law.[128] The Subcommittee hopes that as Burma proceeds along the path to democratic reform, it will address these critical weaknesses in its constitutional structure and judicial institutions. (ii) The Security SectorThe evidence that the Subcommittee received has also convinced us that securing the rule of law in Burma will require the wholesale reform of the entire security apparatus in Burma. We recognize that reforming the military and improving its adherence to international human rights and humanitarian law obligations and standards will be a slow process extending over many years. However, we wish to draw particular attention to the urgent need to begin reforming the Burmese police forces. Witnesses from DFAIT emphasized that the treatment of prisoners is an ongoing concern in Burma.[129] Mr. Din stated that “[l]aw enforcement officials are brutal and dangerous, and arbitrary detention and torture are their only tools to get confessions from the accused.”[130] He also emphasized that civilian governments did not necessarily have effective control over the police.[131] The Subcommittee would like to stress that international law absolutely prohibits any form of torture, as well as all inhuman and degrading treatment.[132] This prohibition extends to treatment inflicted on detainees by security forces or prison officials in the context of interrogations or as a form of punishment of persons under any form of detention or imprisonment.[133] We also note that international human rights standards prohibit the police from using disproportionate or unnecessary force in the exercise of their duties,[134] prohibit corporal punishment, and provide useful guidance relating to humane conditions of detention aimed at preventing cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment.[135] The Subcommittee believes that a principled, effective, and accountable police force is a cornerstone of democracy. Law enforcement officials play a vital role in the protection of the rights to life, liberty and security of the person guaranteed under the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. In our view, a police force serves its community most effectively when it respects the human rights and human dignity of both the victims of crime and alleged perpetrators. Likewise, a humane prison system staffed by well-trained officials is critical to the successful re-integration of offenders into society and to the maintenance of public trust in the state’s ability to fairly enforce the law. We hope that the Burmese government will proceed with reforms to its national police and security forces and prison system as quickly as possible, including taking steps to ensure that these forces are subject to effective civilian control, oversight and accountability. The Subcommittee also believes that the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) can play a useful role in monitoring conditions of detention. In our view, the eradication of torture and ill-treatment by those with a duty to protect the people of Burma should be a particular focus of reform efforts in the country. (iii) The National Human Rights CommissionEarlier in this report, the Subcommittee recognized that the establishment of a national human rights commission by the President of Burma represented a significant step on the path to reform, but noted our concern that it currently lacked an appropriate legislative basis. Although witnesses welcomed the establishment of the Commission, they also expressed concern about its lack of independence from the government and the possible involvement of some members of the Commission in past human rights abuses and violations of international humanitarian law.[136] Witnesses also expressed disappointment with the Commission’s activities to date. Mr. Davis and Inter Pares indicated that the Commission had refused to investigate human rights violations in Kachin State or to accept cases related to alleged human rights violations in the region, where an armed conflict is ongoing.[137] In his March 2012 report, the Special Rapporteur on human rights in Myanmar set out the Commission’s reasons for refusal, as explained by the Commission’s Chairman:

However, the Commission appears to have changed its position. The Special Rapporteur on Myanmar reported that by July of 2012, the Commission had begun to undertake some work in Kachin State.[139] The Subcommittee believes that national human rights institutions can play a useful role in ensuring that universal human rights principles are effectively disseminated and applied, especially in countries emerging from periods of repression or armed conflict.In order to be effective, however, these institutions need to be able to carry out their tasks independently and effectively. Witnesses referred the Subcommittee to the internationally recognized Paris Principles, which set out key standards to help national human rights institutions meet these goals. In particular, national human rights commissions need to have the independence to determine which cases and issues they will address and the capacity, resources and will to effectively assess alleged human rights violations and abuses.[140] In light of the information before it, the Subcommittee is concerned that Burma’s Human Rights Commission is still far from meeting these standards. The Subcommittee was pleased to learn that the Commission has reversed its previous position on human rights investigations in Kachin State. We sincerely hope that the Commission will take a proactive approach to these investigations in the future. In particular, we believe that the Commission needs to strengthen both its capacity and its will to undertake effective and independent investigations into alleged human rights violations by the Burmese military and other state security forces, as well as investigating the actions of non-state armed groups. 3. Lack of Respect and Protection for Other Civil and Political RightsWitnesses told the Subcommittee that many human rights protections in Burma either were not enforced, or were subject to significant limitations permitted by the Constitution. For example, we were told that in practice, freedom of movement is limited and travellers must regularly clear check-points and register wherever they go — even for such minor journeys as an overnight stay at the home of a friend or relative.[141] Arbitrary detention and arbitrary deprivation of property, a lack of respect for minority cultural, linguistic and religious rights, and violations of the right to freedom of association continue.[142] The Subcommittee heard that despite the Burmese government’s ratification of the Palermo Protocol, human trafficking remains a significant problem, particularly in areas affected by armed conflict and major development projects.[143] Forced labour remains common in some ethnic minority areas, where local authorities and the military order villagers to assist with road construction, for-profit agricultural projects and other forms of manual labour without compensation.[144] Further, the 2008 constitution contains a provision that could be interpreted to permit forced labour.[145] Although there is now greater respect for freedom of expression and freedom of the press, and pre-publication censorship of the press has been abolished, it is nonetheless true that the Press Scrutiny and Registration Division, the government’s media censorship body, now will review media articles post-publication. Publication of offensive articles has the potential to subject journalists to harsh punishments, including “fines, imprisonment, suspension, or forced closure.”[146]The Subcommittee agrees with the submission that the new law has the potential to entrench self-censorship in the media by preventing journalists from pushing the limits of permissible speech and instead ensuring that they will stay “well short of them.”[147]We reiterate our strongly held view that freedom of expression, including an uncensored, rigorous and professional media, is critical to ensuring that democracy takes root in Burma and that the human rights of all individuals in the country are protected and respected. In the view of one witness, the vagueness and over-breadth of many provisions in the Constitution permit and facilitate arbitrary, improper and abusive decisions and restrictions on human rights.[148] In addition, although the 2008 Constitution enshrines certain human rights, the vast majority of these rights are guaranteed only to Burmese citizens.[149] Burma’s persistent refusal to recognize the Rohingya ethnic minority as citizens makes the restriction of human rights protections only to “citizens” particularly significant. The Subcommittee notes that the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and international human rights treaties, in contrast, require states to protect and respect the rights of all people under their jurisdiction. a. Political Prisoners and Arbitrary DetentionThe Subcommittee is deeply concerned at the continued detention of political prisoners in Burma and over recent arrests of individuals for the peaceful exercise of their human rights. Mr. Din informed the Subcommittee that the Burmese regime has consistently denied the existence of political prisoners in the country, instead insisting that all prisoners had been convicted for violations of law.[150] This raises an important challenge in assessing Burma’s progress in relation to the release of political prisoners: there is no international standard to determine which individuals are “political prisoners” and which individuals are “criminal convicts.” Although the term “political prisoner” is popularly understood to refer to those who are imprisoned primarily on the basis of their political beliefs, rather than for the commission of a crime, there is no agreed definition of the term under international law.[151] The Subcommittee notes that around the world, individuals may be detained, tried and imprisoned for alleged criminal activity based on their political opinions, perceived political motivations, because of the political nature of their acts, or because of the political motivations of the authorities. Moreover, the Subcommittee notes that in Burma, as in other countries, individuals may be targeted for arbitrary detention out of religious, ethnic or other discriminatory motives. In the Subcommittee’s view, it is important to distinguish between individuals who have actually committed acts of violence and those who hold or express opinions or beliefs peacefully. We believe that all those imprisoned, in Burma or any other country, for peacefully exercising their internationally recognized human rights, in particular their rights to freedom of opinion, expression, association, assembly, religion or belief, ought to be immediately and unconditionally released. The Subcommittee also acknowledges that some individuals imprisoned in Burma may have committed or advocated acts of violence as a means of achieving their political goals, or they may have committed other types of crimes that are defined in a manner that meets international human rights standards, such as crimes involving corruption. We stress that all such individuals must benefit from the full range of fair trial rights under international law, including trial before an independent and impartial tribunal for the commission of crimes defined in accordance with international human rights standards, and on charges that are sufficiently well defined to afford the individual their right to full answer and defence. We do not consider that mere association with an ethnic armed group or its political wing, in the context of Burma’s decades of internal conflict, should automatically disentitle an individual from being considered a “political prisoner.” However, whether such individuals ought to be considered “political prisoners” would need to be considered on a case-by-case basis taking account of the circumstances of each case. Overall, we believe that the situation of imprisoned members of ethnic armed groups ought to be considered in the context of a comprehensive national reconciliation process that stresses the right to truth for victims, as well as accountability for perpetrators of serious violations of international humanitarian law and gross violations or abuses of internationally protected human rights. Witnesses pointed out that despite the recent releases of political prisoners, most of the laws under which those individuals were detained, charged, and convicted remain in force.[152] Moreover, many of the political prisoners who have been released to date have been freed under subsection 401(1) of the Code of Criminal Procedure, a provision that temporarily suspends a prison sentence. These individuals can be re-arrested without a warrant to serve the remainder of their term, and possibly an additional sentence.[153] Mr. Din told the Subcommittee in May of 2012 that these individuals were not yet truly free and illustrated this point by referring to the case of Zargana, “the most famous comedian of Burma.” According to the information the Subcommittee received, Zargana “was sentenced to 59 years imprisonment in June 2008. His sentence was later commuted to 35 years. Upon his release, he had served 3 years and 3 months in prison; however he still owes 31 years and 9 months to President U Thein Sein. It is a very heavy weight sitting on his shoulders at all times.”[154] Estimates of the number of political prisoners who remain in detention vary, but there are thought to be a significant number remaining.[155] The Subcommittee is extremely disturbed by allegations that the Burmese government continues to detain and imprison new individuals on the basis of their political beliefs or for the peaceful exercise of their human rights, despite its stated commitment to reform. Mr. Davis told us that “March [2012] saw the highest number of arrests in two years, including 43 people who have been jailed in relation to development projects for things like refusing forced relocation orders, and for distributing T-shirts protesting a gas pipeline.”[156] Similarly, six locally engaged staff members of the United Nations and a number of staff members of international NGOs working to address humanitarian needs arising out of communal violence that occurred in Rakhine State in June 2012 were arrested and detained. The Special Rapporteur for human rights in Myanmar, indicated at the end of a fact-finding visit in early August 2012 that he had “serious concerns about the treatment of these individuals during detention” and expressed his view that “the charges against them are unfounded and that their due process rights have been denied,” a situation similar to that of other political prisoners. The Special Rapporteur has called for the immediate release of these individuals and a review of their cases. While some of these individuals have since been released, including the UN staff members, others remain in detention.[157] The Subcommittee wishes to express its firm conviction that the Government of Canada ought to continue to call for the immediate and unconditional release of all political prisoners in Burma. B. Concerns with Respect to Economic, Social and Cultural Rights1. Setting the Stage: Economic, Social and Cultural Rights in BurmaThe ultimate goal of international human rights law is the creation of free societies where individuals can live in dignity, free of fear and want. Different states may choose different means to reach this goal. Nevertheless, one of the fundamental functions and obligations of any government is to create, through national effort and international co-operation and in accordance with the resources of each society, the social conditions under which all people within its jurisdiction may fully enjoy their social, economic and cultural rights. Some key social, economic and cultural rights include, for all persons without discrimination:

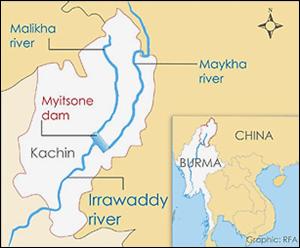

Burma is an impoverished country that has been subject to decades of military misrule. As Burma begins its democratic transition, the Subcommittee was told that significant development challenges will need to be overcome in order to set the people of Burma on the path towards the progressive realization and enjoyment of their economic, social and cultural rights.[159] Mr. Jeff Nankivell, from CIDA, summarized the situation this way: According to the 2011 UN Human Development Report, Burma ranked 149th out of 187 countries on a composite measure of income per-capita, life expectancy and education levels. In the border regions where fighting continues between the national army and armed non-state ethnic groups, there is evidence that the depth of poverty is considerably greater than the national average for Burma. In addition to impeding long-term social and economic development in the affected regions, these long-standing conflicts have resulted in widespread displacement within Burma and migration across borders.[160] Illustrating some of the challenges Burma faces in building the capacity to implement necessary reforms, the 2011 United Nations Development Program (UNDP) Human Development report indicates that the mean number of years of schooling in Burma is 4.0. In contrast, the mean in the Asia-Pacific region as a whole is 7.2 years.[161] Only 18% of adult women and 17.6% of adult men in Burma have completed schooling to the secondary level or higher.[162] In addition, the country lacks infrastructure and communications are difficult, especially since there is little mobile telephone capacity.[163] Witnesses before the Subcommittee stressed that economic development in Burma is an important goal, necessary to both the realization of economic, social and cultural rights for Burma’s people and for the entrenchment of recent democratic reforms.[164] Mr. Giokas told the Subcommittee that Burma will need to attract international investment in order to provide jobs and economic activity for the people of the country. “Without that,” he said, “everything else will likely become problematic.”[165] He stressed that in order for democratic development to succeed, Burma needs its people to be “gainfully employed or feeling that there are prospects, hope and a future for them and their families.”[166] The Subcommittee agrees with Mr. Nankivell’s assessment that for economic development to be successful in Burma, the country will need to ensure sufficient focus on grass roots economic development. We were encouraged to learn that World Bank has recently reached an agreement with the Government of Burma to set up a country office. The Bank is preparing a package of grants of up to US$85 million to fund “community-driven development programs” under which community members will select the development projects that they most need, including in border and conflict areas.[167] 2. Reports of Positive DevelopmentsThe Subcommittee did not receive evidence from witnesses regarding positive developments in the field of economic, social and cultural rights in Burma. We wish to note, however, in the interest of presenting a fair picture of economic, social and cultural rights in Burma, that the Special Rapporteur for human rights in Myanmar has reported that a variety of economic reforms have been introduced by the Burmese government to pave the way towards the introduction of a market economy, to encourage foreign investment, and promote economic growth.[168] The Special Rapporteur, whose reports were referred to as a reliable source of information by a number of witnesses, indicated in March 2012 that President Thein Sein’s reform agenda contains a number of commitments in relation to economic, social and cultural rights, including: “the safeguarding of farmers’ and labour rights, the creation of jobs, the overhauling of public health care and social security, raising education and health standards and the promotion of environmental conservation.”[169] The President also ordered a halt to construction of the controversial Myitsone Dam, located in Kachin State, in September 2011 in response to popular protests. These protests resulted from local concerns about the negative social and environmental impacts of the project. Similarly, in January 2012, the President also suspended the construction of a coal power plan in the Dawei special economic zone, also following popular protests over negative social and environmental impacts.[170] 3. Current Concerns: Human Rights Violations and Abuses Prevent “Development” Projects from Benefitting the Burmese PeopleThe evidence presented to the Subcommittee underscored that respect for civil and political rights in Burma is closely linked to the Burmese people’s enjoyment of the social and economic benefits of development. In terms of economic liberalization, Mr. Giokas told the Subcommittee that Burma is “charging ahead with reforms that they don't really have the capacity to implement properly.”[171] He stressed that Burma currently provides a very difficult investment environment.[172] Inter Pares submitted that “Burma has no regulatory framework whatsoever to oversee the sustainability of development projects or extractive industry, or to protect local people from the negative impacts of projects.”[173] Mr. Davis shared this view.[174] Mr. Din identified the crux of the issue when he asked how Burma could develop “when you don't have the rule of law, you don't have proper business guidelines, and you don't have a governance system that grants equal opportunity for all the people inside the country?”[175] To demonstrate their concerns about the lack of an adequate political, legal and regulatory framework within which development projects could be expected to contribute to the welfare of the Burmese people, witnesses highlighted problems created by existing projects, undertaken, in light of Western sanctions, primarily by investors from China, India and Thailand. We were informed that Burmese state-owned and private companies behaved no better.[176] Mr. Din explained that decisions about infrastructure and resource development projects are routinely made without consulting the affected communities and without proper environmental or social impact assessments. A similar point was also made by the Karen Human Rights Group, which stated that villagers often have no opportunity to express their concerns about the ways in which development projects may affect their agricultural land or livelihoods, nor do they have an opportunity to negotiate what they believe to be “fair” compensation for anticipated losses to property or their ability to earn a living.[177] Inter Pares submitted that “[w]ell-documented practice to date illustrates a pattern of resource extraction development projects accompanied by massive militarization of the area and widespread human rights abuses.”[178] To make matters worse, many of the benefits of resource, infrastructure and development projects do not reach local people, but are instead funnelled out of the country. Mr. Humphries informed the Subcommittee, for example, that nearly all of the power generated from a series of massive hydroelectric projects in Burma goes to China, while the Burmese live with widespread electricity shortages.[179] Witnesses also highlighted the links between Burma’s large-scale infrastructure projects and its internal armed conflicts with ethnic minorities. We were told that the 17-year ceasefire in Kachin State ended in 2011, when fighting broke out in a strategically important area at the headwaters of the Irrawaddy River where a major hydroelectric project — the Myitsone Dam — was being constructed by Chinese investors.[180] In the words of Inter Pares, as a result of large-scale development projects undertaken in Kachin State since the ceasefire, the Kachin people saw their forests destroyed, and their land confiscated for plantation agriculture or destroyed by mine tailings. During the first 10 years of the ceasefire [between the Kachin Independence Army and the Burmese military],[181] the number of Burma Army battalions more than doubled to support these projects, resulting in increased forced labour, sexual violence, increased drug trafficking and addiction, extortion and other abuses with impunity.[182] Mr. Humphries also stressed that the persecution of the Kachin people by the Burmese military, discussed in detail later in this report, is based partly on the military’s desire to control the resource wealth in the area.[183] We were told that this history of human rights violations and exploitation under the guise of “economic development” was an important factor in the breakdown of the ceasefire, following an influx of Burmese troops to support the construction of the Myitsone Dam in Kachin State. In Mr. Davis’ view, the Kachin Independence Organization[184] also sees the Myitsone Dam project as a strategic threat that will undermine Kachin military positions and increase the number of Burmese troops in previously Kachin-controlled areas.[185] The Kachin Independence Organization, said Inter Pares, has “refused to negotiate a ceasefire based on ‘development’ unless there is a clear mechanism to resolve political issues.”[186] Figure 3: Map of the Myitsone Dam in Kachin State, Burma

Source: © Radio Free Asia[187] Reports of forced labour in connection with large-scale economic development projects continue to be widespread throughout the country, especially in ethnic minority areas. In some Karen areas, the Burmese military units assigned to provide security for development projects are reported to extort arbitrary fees from villagers before allowing them to travel and transport goods.[188] Overall, we were told that instead of improving the lives of the people of Burma, “[t]hese projects have driven the people into deep poverty, landlessness, and displacement.”[189] Based on concerns stemming from current development practices in Burma, witnesses stressed the critical importance of putting into place national laws and regulations to protect people, the environment and society in accordance with international human rights standards and standards on corporate social and environmental responsibility. Without such a framework, we were told that the people of Burma will not see the positive effects of development.[190] a. Land RightsWitnesses highlighted the critical importance of the protection of land, housing and property rights for villagers and ordinary people in Burma, in light of recent reforms expected to lead to an increase in foreign investment. They noted that in Burma, development projects are often accompanied by land confiscation without just compensation, causing people to lose their homes, their villages and their status.[191] We were informed that the Burmese military has traditionally attempted to consolidate its control of areas where ceasefire agreements have been reached by handing out land and business concessions that usually result in the confiscation of villagers’ homes and property without compensation, and ultimately, in forced displacement of populations.[192] In fact, Mr. Din identified land confiscation as the most pressing development issue facing Burma today. He told the Subcommittee that in ethnic minority areas, “there are more and more violations of land and housing rights caused by infrastructure and development projects, natural resources exploitation, and land confiscation.”[193] Members queried witnesses about this pressing issue, and about the possibility that recent reforms could actually be used to legitimize or facilitate land grabbing. The Subcommittee learned that although the 2008 constitution guarantees the right to land and private property ownership,[194] this protection is largely ineffective in practice.[195] We were also informed that a new land law has not dispelled fears of land grabbing because it permits land confiscation in matters of “national interest.”[196] Discussing the controversial Myitsone Dam project in Kachin State, now suspended by order of the President, Mr. Humphries illustrated the problem: When [the Burmese authorities] want to build a power dam, as they did up north of Myitkyina [the capital city of Kachin state], they just said they were building the power dam. It's the fifteenth largest power dam in the world, and they just started moving out the Kachin by the thousands. The commitments and the things that [the Government] said they would do, such as giving [the displaced Kachin] a new farm or new property, they never did. They just took it. Then they brought in about 10,000 migrant workers from China — I was living there at that time. So [the Kachin] don't even get the benefit of helping to make money by building these things. …[197] Similarly, we were told that lands are being confiscated to build a pipeline that will transport natural gas found in the Bay of Bengal, off the coast of Rakhine State in western Burma, through the middle of country and across Shan State in the east, for sale to China, where the pipeline will terminate. We were informed that people who are displaced by these infrastructure and development projects, and those whose land is confiscated without fair compensation have no recourse. There is nowhere to turn for justice. As Mr. Humphries eloquently stated, “[y]ou just lose it; it's gone. And if you complain too much, you're gone.”[198] The Subcommittee notes that “the permanent or temporary removal against their will of individuals, families and/or communities from the homes and/or land which they occupy, without the provision of, and access to, appropriate forms of legal or other protection” (forced evictions) are incompatible with the right to adequate housing guaranteed under the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.[199] Forced evictions violate Burma’s international obligation under the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, as well as its obligation under the Convention on the Rights of the Child.[200] As witnesses pointed out, forced evictions often lead to the violation or abuse of other human rights — for example, the loss of community, culture and status. Forced evictions cause internal displacement and refugee movements and can lead to forcible population transfer, especially in situations of armed conflict. In Burma and elsewhere, such evictions are often accompanied by violence, including armed conflict and communal violence. Women and children are especially vulnerable following such forced evictions and face a heightened risk of sexual abuse and violence when they are left homeless.[201] The Subcommittee stresses that international human rights standards require that people be protected by law from unfair eviction from their homes and land. International standards mandate a number of procedural protections that Burma should apply before undertaking any eviction:

In a country like Burma with extreme inequalities of wealth and deep social divisions, where individuals and communities affected by evictions are unable to care for themselves, international human rights standards require the state to take all appropriate measures consistent with the resources available to it, in order to ensure that the affected people have access to a resettlement process, productive land or alternative housing.[203] The Subcommittee believes that Burma urgently needs to revise its proposed draft land legislation in order to clearly prevent and punish forced evictions by private persons and public actors. Individuals need to have access to independent and impartial legal recourse, including appropriate procedural protections, where just compensation has not been paid for their property or damage caused to it. To ensure that people have access to justice, including legal remedies for eviction, Burma should also aspire to provide legal aid for individuals to challenge their evictions in court. The Subcommittee believes that the Government of Canada should continue to stress the importance of implementing these human rights protections in its relationship with the Government of Burma, as well as in its advice to private corporations considering doing business in the country. 4. Current Concerns: Pervasive Corruption and the Need for Responsible InvestmentMr. Giokas informed the Subcommittee that the personal links between members of the military and the country’s major infrastructure and development projects pose a major challenge for would-be investors from countries like Canada.[204] Mr. Din explained that these personal relationships enabled corruption in Burma, preventing the country’s natural resource wealth from benefitting the people.[205] Indeed, the Special Rapporteur on human rights in Myanmar noted in March 2012 that: [T]he multi-billion-dollar profits from natural gas sales to Thailand have not been used to improve the educational infrastructure in the country. According to reliable sources, these revenues appear to be stored in offshore bank accounts, outside the national budget. … The funds from the sale of natural gas are estimated to account for 70 per cent of the country’s total foreign exchange reserves, with sales totalling around $3 billion annually. If these funds had been included in the State budget, they would have accounted for 57 per cent of the total budget revenue. Instead, they contributed less than 1 per cent of total budget revenue, with much of this revenue reportedly never entering Myanmar. These funds need to be included in the Government’s budget and managed transparently with proper checks and balances.[206] The Subcommittee wishes to underline the fact that corruption and poor governance have a negative effect on the enjoyment and protection of individual rights. Corruption prevents states from delivering social services necessary for the progressive realization of economic, social and cultural rights and creates disparities in access to public goods between those with or without influence on the authorities. The economically and politically disadvantaged inevitably suffer greater marginalization in societies like Burma where corruption is prevalent. Corruption also weakens democratic governance and the rule of law. Important public policy decisions are not taken with the interests of the people in mind, but rather to advance certain personal interests, which can lead to a loss of support for democratic institutions in the long run. In Burma, the Subcommittee was told that judicial independence is compromised and corrupt justice-sector officials impede reform. Such practices weaken the right to a fair trial and compromise the accountability structures that are necessary to combat impunity because laws are not consistently applied and violators are not consistently punished.[207] The Subcommittee believes that Burma needs to address swiftly and decisively the problem of systemic corruption and in particular, corruption in its major infrastructure, resource and development projects, if it hopes to entrench democratic reforms. We were told that Canadian companies should not invest in mining operations or the extractive resources sector until and unless there are regulations put in place that are consistent with internationally recognized social responsibility and environmental standards. Mr. Din advocated the adoption by Canada of “binding principles” requiring corporations investing in Burma to respect labour rights and to ensure that their activities do not cause undue negative social and environmental impacts for local communities.[208] In the long run, the Subcommittee believes that improving transparency, accountability and resource governance in Burma will be critical to ensuring that infrastructure, resource extraction, hydro power and other development projects in Burma contribute to poverty reduction and create a business environment in which foreign investors can operate responsibly. The duty to enact an appropriate legal, institutional and budgetary framework that will ensure that the benefits of Burma’s wealth reach its people lies primarily with the Government of Burma. In particular, this is the task of the civilian MPs and the executive who will need to take steps to meet the economic, social and cultural aspirations of their constituents if they hope to remain in office following free and fair elections in 2015. The Subcommittee agrees with witnesses who urged foreign investors to proceed with great caution before venturing into dealings involving the extraction of natural resources, infrastructure, and other large-scale economic development projects. We note that Canadians remain barred from doing business with certain individuals in Burma and that Canada’s Corruption of Foreign Public Officials Act imposes criminal penalties, including imprisonment, for bribery of foreign public officials.[209] In addition, the Subcommittee expects that any Canadian company considering investing in Burma will ensure that its operations are compliant with internationally recognized corporate social responsibility standards supported by the Government of Canada, including the following:

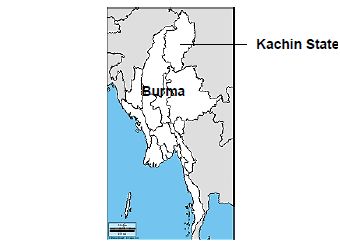

The Subcommittee also wishes to draw attention to the fact that the Office of the Extractive Sector Social Responsibility Counsellor is available to assist stakeholders to mediate disputes, under certain conditions, involving the activities of Canadian extractive resources companies abroad.[213] The Subcommittee believes strongly that the people of Burma, without discrimination, must be able to benefit from economic development within the country, earn their livelihoods successfully in a fair work environment, provide for their families, and be assured of adequate access to health care and education during this time of transition. We agree with Mr. Giokas that Burma will need to work on building the “institutions and architecture to attract the type of investment they will require to create prosperity in their country.”[214] Given Canada’s expertise in the extractive resources sector, the Subcommittee observes that there may be a useful role for Canada and Canadians to play in providing capacity-building assistance in this regard. C. Specific Concerns Regarding the Situation of Ethnic Minority Groups1. IntroductionThroughout our study, witnesses stressed that the democratic and human rights progress that has occurred in central Burma has not yet reached the country’s border regions. These areas are populated by different ethnic minority groups, many of whom have been at war with the Burmese government for decades. According to Mr. Davis, Burma's ethnic minorities make up a third of the country's population, and they continue to bear the brunt of the military's crimes. Minority groups remain extremely sceptical of the changes in Burma, and for good reason. Ethnic people have faced abuse and oppression by the Burmese government for more than 60 years, and they're understandably reluctant to embrace the announced changes coming from their government. They do not trust the government, and so far, they have not benefited from the changes in Burma.[215] Echoing this sentiment, Mr. Humphries told us that in ethnic minority areas, the lack of civilian control over the military has created a great deal of confusion about the constitution and the role of Parliament. Despite recent changes in central Burma, the Commander-in-Chief and local military commanders still appear to have complete authority in these regions.[216] Mrs. Humphries added that as a result, “in practice, there is a very real policy of fear and intimidation at all levels” in these parts of the country.[217] The Subcommittee is gravely concerned about the credible reports, including eye-witness testimony, which we have received regarding the continued commission of war crimes, crimes against humanity and grave human rights violations and abuses in Burma’s border regions. We believe that a negotiated political settlement with ethnic minority groups, recognition and acknowledgement of crimes that have been committed, some genuine form of accountability for perpetrators, and effective remedies for victims will be needed to establish a peaceful, free and democratic Burma. a. Principal Ethnic Groups and Ethnic ArmiesBurma is home to a large number of different ethnic groups. Among these are the Kachin (northeast Burma), Chin (northwest Burma), Shan (eastern and northeastern Burma), Wa (eastern and northeastern Burma), Konkang (eastern and northeastern Burma), Karen (eastern Burma), Karenni (eastern and southeastern Burma), Kayan (eastern and southeastern Burma), and Mon (southeastern Burma), all of whom have a history of organized, armed rebellion against the Burmese State since the end of the colonial period in 1948. Although many ethnic armed groups reached ceasefire agreements with the Burmese junta during the 1990s, the Karen National Union, the Karenni National Progressive Party, the Shan State Army — South, and the Chin National Front did not reach lasting agreements and brutal, low-level fighting in the states dominated by these ethnic groups continued. With the exception of the Kokang, whose ethnic army was transformed into a border guard force under Burmese control following a Burmese military offensive in 2010, all of these groups continue to maintain standing armies,[218] and many have negotiated new ceasefire agreements in the last two years.[219] Witnesses stressed that despite the existence of ceasefire agreements, the political grievances underlying these armed conflicts have remained unaddressed and unresolved.[220] In addition to these groups, the Rakhine and Rohingya ethnic groups live in Rakhine State, in western Burma, where there is little recent history of armed conflict.The Rohingya are concentrated in three northwestern townships of the state.[221] A number of smaller ethnic groups also exist throughout the country, primarily in the mountainous border regions. Complementing Burma’s ethnic diversity, a variety of different religions are practiced by ethnic minority groups. While members of ethnic minority groups share the majority Buddhist faith, a number of ethnic minority groups are predominantly Christian, particularly the Kachin and the Chin. The Rohingya in western Burma are generally Muslim, while the Rakhine are predominantly Buddhist. There are also Muslim, Hindu and animist populations of various minority ethnicities living in various regions of the country. b. A History of Political Marginalization and Armed ConflictSeveral witnesses before the Subcommittee highlighted the deep historical roots of ethnic grievances and armed conflicts in the country and stressed that understanding this history was relevant to reaching a durable political settlement. From 1824 until shortly after the Second World War, Burma was a British colony. During this period, the British employed a divide and conquer strategy, essentially pitting the aspirations and military capability of the ethnic groups living in what are now the border regions of Burma against those of the Burman majority.[222] Large-scale immigration from British India as well as China also occurred during this period.[223] In the immediate post-war period, the Rohingya leadership expressed both a desire for independence and a desire to be incorporated into what was then east Pakistan (now Bangladesh). A report submitted to the Subcommittee by prominent international lawyer, Professor William Schabas, argues that the influx of immigration from British India during the colonial period, coupled with this threat to secede from the Union of Burma “on the eve of independence” forms part of the basis for the insistence of successive Burmese governments that the Rohingya represent a foreign threat to the territorial integrity of the country.[224] Mr. Humphries told the Subcommittee about the importance of a conference held in February 1947, called the Panglong Conference. It was at the Panglong Conference that representatives of the Kachin, Chin and Shan ethnic groups met with the Burmese political leader General Aung San and agreed to join a future, independent Union of Burma on the understanding that their regions would retain internal autonomy, receive a guaranteed level of political representation at the national level, and a guaranteed share of the country’s wealth (this agreement is referred to as the Panglong Agreement).[225] Karen leaders wished to establish an independent state and so declined to attend the conference. Mon and other ethnic leaders were not invited.[226] As a result, power-sharing arrangements in respect of different ethnic groups remained uneven and unequal. In July 1947, General Aung San was assassinated, along with most of his cabinet. In January 1948, Burma became independent under a constitution that recognized the country’s ethnic and cultural diversity and which provided various special rights for certain ethnic groups;[227] however, the various ethnic minority groups were not given the option of forming independent states, as they had expected. Almost immediately, a number of ethnic minority groups who had not signed the Panglong Agreement rebelled, including the Karen in eastern Burma, and groups with close ethnic ties to China and political links to the Chinese communist party. During the late 1950s and early 1960s, increasing political centralization and marginalization increased ethnic dissatisfaction and eventually the Shan, Kachin and Chin also rebelled.[228] Following Burmese independence, the Rohingya, like other ethnic minorities, became citizens of Burma. In 1961, a ceasefire agreement with Rohingya armed groups was reached, establishing a separate administrative area that gave some autonomy to Rohingya-dominated areas of Rakhine State.[229] In 1962, in the name of ensuring national unity and preventing the break-up of the country, General Ne Win led a coup d’état, replacing the elected government with the “Revolutionary Council,” a military dictatorship.[230] Under the dictatorship of General Ne Win, the Burmese junta instituted radical social and economic policies designed to isolate Burma from the outside world and to create a socialist state. The central government refused to accommodate ethnic aspirations, instead embarking on a campaign of “burmanization” of ethnic minorities, with the goal of creating a single, uniform nationality throughout the country that was Burman and Buddhist in character. In effect, we were told that this amounted to a campaign of forced assimilation designed to destroy the distinct cultural, linguistic and religious identities of Burma’s ethnic minority groups.In 1974, a new constitution creating a unitary state was promulgated.[231] Witnesses told the Subcommittee that this period was characterized by protracted armed conflicts involving various ethnic minority groups, which fought each other as well as the Burmese military, and by flagrant violations of international law perpetrated by Burmese troops in ethnic areas as they tried to cut off any assistance to armed groups from the local population.[232] Under General Ne Win, Burma also expelled thousands of ethnic South Asians who had controlled large portions of the colonial-era economy, as well as ethnic Chinese entrepreneurs. It also commenced a concerted campaign of racial persecution against the Rohingya ethnic minority in western Burma, including the promulgation of a new citizenship law in 1982 that effectively made it impossible for Rohingya to claim Burmese citizenship.[233] Ceasefire agreements were reached with a number of ethnic groups in the 1990s, although notably not with the Karen or the Karenni. Armed conflict intensified again in 2009 after the Burmese military government unexpectedly issued an instruction requiring ethnic armies to transform into “Border Guard Forces” under the partial command of the Burmese military.[234] Mr. Humphries told us that the ethnic armies objected strongly to this plan, which would have given the Burmese military significant authority over their troops without granting ethnic commanders senior positions within the Burmese military. For example, he said that the Kachin Independence Organization believed this initiative failed to recognize their right to autonomy within the Union of Burma, and that it would have removed their power and ability to help their people move forward.[235] 2. Ongoing Discrimination, Violations of the Right to Freedom of Religion and Children’s Right to EducationWitnesses told us that ethnic minority groups still suffer disproportionately from human rights violations by the Burmese government and military. The Subcommittee learned that many of these violations stem from discriminatory state policies that continue to be enforced in border regions. The Subcommittee’s attention was also drawn, in particular, to serious violations of ethnic minority groups’ right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion. Mr. Davis told us that although the discriminatory “Burmanization” policy is no longer officially in force, it still informs the thinking of many senior generals.[236] The Subcommittee recalls that international human rights law and standards prohibit discrimination, which comes in multiple forms. Discrimination has been defined as any distinction, exclusion, restriction or preference or other differential treatment that is directly or indirectly based on the prohibited grounds of discrimination [such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status] and which has the intention or effect of nullifying or impairing the recognition, enjoyment or exercise, on an equal footing, of internationally recognized human rights.[237] We note also that the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion has been described as “far-reaching and profound,” including “freedom of thought on all matters, personal conviction and the commitment to religion or belief, whether manifested individually or in community with others.”[238] This right also protects the freedom to manifest one’s religious beliefs “in worship, observance, practice and teaching” individually or as part of a religious community, including through building places of worship, and displaying religious symbols.[239] The practice and teaching of religious beliefs include “acts integral to the conduct by religious groups of their basic affairs, such as the freedom to choose their religious leaders, priests and teachers, the freedom to establish seminaries or religious schools and the freedom to prepare and distribute religious texts or publications.”[240] However, international human rights standards do not protect or permit manifestations of religious belief that constitute advocacy of religious, racial or national hatred, or which incite discrimination, violence or hostility.[241] Mr. Giokas confirmed that the Government of Canada has serious concerns about respect for freedom of religion in Burma, in particular in areas of armed conflict, such as Kachin State.[242] Mrs. Humphries echoed this sentiment, telling the Subcommittee that “[s]o-called freedom of religion is greatly controlled by the government.”[243] Professor William Schabas, in his written submission to the Subcommittee, provided documentation indicating that in northwestern Rakhine State, Rohingya are prohibited from building mosques or establishing madrassas to educate their children. Rohingya also have reportedly been forced to destroy mosques and build Buddhist pagodas in their place.[244] Dr. Uddin told us that Muslims in Burma face pressure from the state to convert to Buddhism,[245] saying a great religion has been hijacked by these extremists in the Burmese military and government. We all know the theology of Buddha says that you cannot kill one ant or insect. A great religion of peace has been hijacked and used like many other religions. We have seen that in our own religion too [Islam]. So it's been hijacked and this religious preference is an ongoing thing ....[246] The Subcommittee learned that discrimination against ethnic minority groups on the basis of religion is closely connected to other forms of discrimination on the basis of ethnicity, language and culture in Burma. In her home of Kachin State, Mrs. Humphries told us that in practice, even today, the Kachin people’s “ethnic language, culture, and tradition are all being stripped away by force.”[247] Similarly, we were told that the Chin people “have suffered deep-rooted, institutionalized discrimination on the dual basis of their ethnicity (Chin) and religion (Christian).”[248] Illustrating this problem, Mr. Davis informed us that when the state governments were reorganized by the military dictatorship in 2008, the junta failed to create ministries of education or health in Chin State.[249] The chronic underfunding of the state education system in that region requires families to pay annual school fees and the cost of school supplies, as well as supplementing teachers’ salaries. Many Chin families cannot afford these costs. As a result, the only option for many Chin is to send their children to the free or lower cost “Border Areas National Races Youth Development Training Schools,” run by the Education and Training Department within the Ministry for Border Affairs — which is dominated by the military.[250] We were informed that although these schools exist throughout Burma, Chin children are specifically targeted for recruitment, where they are “prevented from practising Christianity and face coercion to convert to Buddhism.”[251] Informal community primary schools set up to teach Chin children in the Chin language have reportedly been banned since 1998.[252] In commercial relations, Christian Chin also face pressure to convert to Buddhism from business associates who do not wish to deal with Christians.[253] Discriminatory practices in education do not appear to be confined to Chin State. The Special Rapporteur on human rights in Myanmar reported in his March 2011 that “[d]espite official acknowledgement of 135 ethnic minority groups with almost 100 local languages, it is not legal to teach in any language except the Myanmar language.”[254] This practice poses a barrier to education for children who speak a minority language and in some places prevents them from learning to read and write in their own language, which means that these children “loose access to part of their culture and traditions.”[255] This information leads the Subcommittee to conclude that despite recent reforms, the Burmese government continues to pursue policies that violate the human rights of minority ethnic groups, in particular the right of all people to freedom of thought, conscience and religion, the right to freedom from discrimination, and the right to education of some ethnic minority children.[256] In particular, forced conversion in an educational setting constitutes a clear violation of the right to freedom of religion. We note further that the Burmese government appears to be failing to protect individuals from discrimination from private persons, creating an environment where people are not free to enjoy their human rights. The Subcommittee observes that Burma has ratified the Convention on the Rights of the Child, which enshrines children’s right to freedom from discrimination and freedom of religion and requires Burma to ensure that childhood education aims at developing respect for the child’s own “cultural identity, language and values.”[257] The Convention provides special protection to children belonging to minority ethnic, religious and linguistic groups, who are explicitly guaranteed the right to enjoy their own culture, to practise their own religion and to use their own language.[258] The reports received by the Subcommittee indicate that the Burmese government is violating its obligations in this regard in parts of Chin State. Dr. Uddin spoke of a lack of religious tolerance in Burma at the present time, which in his opinion had led to “serious clashes” between state forces and religious or ethnic minorities, and between different religious and ethnic groups. He believes, however, that fostering democracy and human rights more broadly will allow religious tolerance to grow in the country. Dr. Uddin told us that he was optimistic that Burma’s democratic transition “will hopefully guarantee some coexistence of religion, and a multi-religion based society could be possible in Burma.”[259] The Subcommittee agrees with the submissions of witnesses who told us that durable peace and prosperity in Burma requires that the Burmese people, their government, and the military come to see the country’s great ethnic and religious diversity as a strength, rather than a weakness. If the government of Burma is sincere about its desire to embrace democratic reform and human rights, it must cease the practices described above, stop discriminatory and other human-rights violating conduct, and prevent harassment and discrimination by non-state actors, including individuals. We urge the Government of Canada to continue to stress the importance of the principles of non-discrimination and religious freedom, without which no democratic society can thrive. The Subcommittee observes that Canada’s Office of Religious Freedom may be able to contribute to the development of greater religious tolerance and respect for diversity in Burma. 3. Armed Conflict and Humanitarian Crisis in Kachin StateFigure 4: Map of Kachin State, Burma[260]