INDU Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

|

CHAPTER 3: CHALLENGES FACING SELECTED INDUSTRIES The Canadian aerospace industry includes more than 400 companies with annual revenues of $22.7 billion in 2007, placing Canada in fourth position behind aerospace industries in the United States, United Kingdom and France, and narrowly ahead of those in Germany, Italy and Japan (see Figure 10). From its most recent trough of $21.3 billion in 2003, the Aerospace Industries Association of Canada estimates that revenues will total $23.6 billion in 2008. The industry has, therefore, grown despite the rapid and steep rise in the value of the Canadian dollar between 2003 and 2007 and the global economic recession that ensued. Indeed, the industry’s average annual rate of growth in revenues of 2.1% in this period — slightly above the annual rate of price inflation — suggests that the industry held its own compared to other manufacturing industries throughout the “commodities boom” period. Figure 10

Source: Aerospace Industries Association of Canada, Submission to the Subcommittee on Canadian Industrial Sectors, April 28, 2009. The Canadian aerospace industry is extraordinarily dependent on foreign buyers of its products. Exports amounted to $18.6 billion in 2007 or 82% of industry revenues. The United States is Canada’s largest market, accounting for $12.6 billion, followed by the Canadian market itself, which was valued at $4.1 billion, and Europe also with sales of $4.1 billion in 2007. Aerospace sales for civil purposes of $17.7 billion (or 78%) dominate sales with military applications of $5 billion (or 22%). The industry employs 82,000 Canadians, including 12,000 scientists and engineers and 20,000 technicians and technologists, paying an average annual salary of approximately $60,000. Industry employment is greatest in Quebec, followed by Ontario, British Columbia, Alberta, Manitoba and Atlantic Canada. A better understanding of this industry and its economic circumstance can be gained when the industry is viewed in terms of its major market segments: (1) aircraft, aircraft parts and components; (2) engines and engine parts; (3) avionics and electro systems; (4) simulation and training; and (5) space. Canada is very competitive and a major player in each of these market segments. In fact, Canadian firms are global market leaders in regional aircraft, business jets, commercial helicopters, small gas turbine engines, landing gear, flight simulation, and space applications. For example, Bombardier, with a 47% share of the regional aircraft market, is the third largest aircraft company, after Boeing and Airbus. Bell Helicopter Textron Canada Limited is the world’s leading producer of rotary wing aircraft. Pratt & Whitney Canada, with a 34% share of the small gas turbine engine market, is a world leading supplier of turbine-powered aviation engines, engine systems and components for business and regional aircraft, and helicopters. CAE Inc., with a 70% share of the visual simulation equipment market, is the world’s leading producer of flight simulators and visual training devices.[16] Finally, Canada’s space industry, working in partnership with the Canadian Space Agency, is a world leader in space robotics and automation (i.e., the Canadarm). Canada is also a world leader in satellite systems (i.e., RADARSAT-1 and RADARSAT-2) that collect, record, store and process satellite-based land information. Canada’s aerospace industry clearly punches above its weight on the world stage. Witnesses provided a few interesting observations on how Canada, a relatively small country, achieved such an elevated status in the world: [W]hen we consider that those countries that rank ahead of us are the benefactors of a massive military presence when compared to Canada’s defence expenditures, the success of our company and our sector is all the more remarkable. Richard Bertrand, Pratt & Whitney Canada, 8: 9:30 Why is CAE a global leader? Part of our success is due to our employees as they continually strive to push the innovation envelope further ... Our success is also the result of supportive government policy that spans back decades. This support has been and must continue to be stable, predictable, and comprehensive. Government support is fundamental to maintain a vibrant and globally competitive aerospace sector. Nathalie Bourque, CAE Inc., 8: 9:25 You’ve described ... winning conditions, and those are important to the success of an industry. ... I would add ... that we also have a very strong civil service within Industry Canada, with whom we work constantly. This is a very big plus also for the industry: to have people who understand the needs and who work very hard at responding to these needs. Claude Lajeunesse, Aerospace Industries Association of Canada, 8: 10:25 At first blush, not many “captains of industry” would boast that their company’s success and competitive advantage is due, in part, to government. However, it must be recognized that the global aerospace industry does not operate in a laissez-faire marketplace. Government intervention in the sector is pervasive within the aerospace and defence industry. Governments around the world use various policy instruments to support aerospace industries operating within their jurisdictions, including funding defence programs and purchases, financing research and development infrastructure, and providing loan guarantees and bank financing for aircraft development and production. In Canada, major federal programs and initiatives used by the aerospace industry include: (1) Strategic Aerospace and Defence Initiative (SADI); (2) Scientific Research and Experimental Development (SR&ED) Tax Incentive Program; (3) Defence Industry Research Program; and (4) the National Research Council’s Institute for Aerospace Research, Aerospace Manufacturing Technology Centre and Industrial Research Assistance Program (IRAP). Industry officials also saluted the efforts of the government in concluding free trade agreements and in its recent decision to negotiate a free trade agreement with the European Union. They stated that such an agreement would make a big difference to all segments of the aerospace industry, if for no other reason than it will help to provide labour mobility, which is one important aspect of their global industry. They also stated that the government should resist protectionism, under whatever guise, and that the role of Canada’s diplomatic missions abroad in terms of promoting the image of Canadian industry was extremely important. The recession has provided challenges to Canada’s aerospace industry in a number of ways, most notably forcing them to cut employment levels and manage costs more thoroughly. In some ways, the global recession has hit the Canadian aerospace industry hard as its customers are predominantly foreigners — commercial airline companies and aircraft leasing companies — that have had to endure the full force of the financial crisis and global recession. [L]ike every business today, it is precarious because every business is subject to the vagaries of the international economic climate. ... The critical component of the challenge we face ... is not our lack of liquidity ... but that of our customers. We can only be as successful as our customers are and our customers face tremendous challenges — airlines as well as leasing companies and individual corporations. Their problem is related to the capital, the cash crunch that is affecting all businesses around the world, the shortage of liquidity in the capital markets. George Haynal, Bombardier Inc., 8: 9:45 Beyond the immediate business cycle, the future of the aerospace industry looks promising. The Aerospace Industries Association of Canada foresees 24,000 new aircraft sales worldwide between 2009 and 2027. This market segment is expected to exceed $3 trillion. Because the industry’s cyclical challenges are mostly foreign in source, the industry focused its request for government assistance on dealing with its structural challenges. Witnesses from the industry asked for five policy improvements of the federal government:

The Canadian chemicals industry, with shipments estimated at $50.6 billion in 2008, is the fourth largest manufacturing subsector in the country. There are approximately 3,000 firms engaged in chemicals production across the country and they employed 78,340 people in 2008 (see Table 5). The industry is also the third largest exporter of manufactured products in the country, with exports valued at $31.3 billion in 2008, 76% of which was destined to the United States. With the global chemicals industry producing an estimated $3 trillion worth of product,[17] Canadian chemicals production represents 1.5% of total world production. Given this relatively small presence within the industry, Canada has traditionally been a net importer country of about $10 billion worth of chemicals and chemical products on an annual basis. Table 5

Source: Statistics Canada, http://www.ic.gc.ca/eic/site/chemicals-chimiques.nsf/eng/bt01203.html. Canada is home to nine of the 10 largest chemicals producers in the world, including BASF, Dow Chemical, DuPont, ExxonMobil, Hexion, Ineos, Lanxess, Sabic and Shell Chemicals. Canada also boasts five large home-grown companies such as Agrium Inc., ERCO Worldwide, Methanex Corporation, Nova Chemicals Corp. and Raymond Industries Inc. Canada’s chemicals industry is heavily concentrated in Ontario (with 42% of the country’s 3,000 firms), Quebec, (26%), and Alberta (11%). Each region has its own distinct strengths and competitive advantages, but the country’s four largest clusters (i.e., Sarnia, Toronto, Montreal and Edmonton) dominate domestic production. The chemicals industry essentially converts raw materials such as oil, natural gas, electricity and minerals into value-added manufactured products, adding anywhere between five and 20 times the value of these inputs. Chemicals are basic building blocks of many manufactured goods as they are found in more than 30,000 different products.[18] An industry representative described the activities of the chemicals industry in the following way: We transform oil, gas, salt, and electricity into chemical products. Those products are then used by a wide variety of other industries, which can include pharmaceuticals, aerospace, auto, plastics, lubricants, and petroleum refining. ... In doing that, we add five to twenty times the value to those base resources through this conversion process, thus directly creating wealth for the economy as well as the other sectors we depend on for the supply of those resources. Richard Paton, Canadian Chemical Producers’ Association, 7: 9:05 Canada’s petrochemical industry is founded on a secure supply of feedstock and a feedstock price advantage. Industry representatives maintain that the industry’s continued livelihood and contribution to the Canadian economy are predicated on preserving and improving these advantages, advantages that are necessary for overcoming transportation, climate and other disadvantages associated with production locations that are often far from their final markets. The industry’s focus on its feedstock is not so surprising once one recognizes that the basic raw materials of chemical products account for about 86% of total manufacturing costs, followed very distantly by energy costs (7%) and labour costs (7%).[19] Forthcoming competition with low-cost Middle East petrochemical suppliers only reinforces this focus: [T]he Middle East is now becoming a huge player because feedstock — as you know, it’s oil or natural gas — is a huge proportion of the cost of our products, and their feedstock costs are 20% or 30% of ours. They need to diversify their economies, so the Middle East is now building huge manufacturing facilities for chemicals. Richard Paton, Canadian Chemical Producers’ Association, 7: 9:35 Industry representatives also indicated that transportation is an important component of the selling price for many chemical products, sometimes exceeding 10% of the selling price.[20] The industry, particularly companies with plants situated in Western Canada, requires competitive freight rates and services to assist them in competing in both domestic and export markets, something that they claim they are not receiving at the present moment. According to an industry representative: There is rail service review that needs to be done. Rail is critical to our industry. We think there is a need for better competition in rail and better service. Richard Paton, Canadian Chemical Producers’ Association, 7: 10:00 Electricity is an important input cost to the many of the industry’s products, varying from 1% to 5% of the total production cost for petrochemical producers to 40% to 70% of total production costs for some inorganic and compressed gas producers.[21] The industry claims that Ontario’s electricity rates for major industrial users are among the highest in Canada. For these reasons, the cost, availability and reliability of electricity remain concerns for competitiveness and plant safety, particularly in Ontario. The chemicals industry has experienced considerable cost pressures from high raw material and energy prices since 2000, and from the relatively high value of the Canadian dollar since 2003. Chemical producers are also concerned about the impact on their operations of environmental regulations. They identified layers of duplicative and sometimes conflicting federal-provincial environmental regulations as a concern. As a consequence of these cost pressures and the relatively high value of the Canadian dollar, the industry has had to contract: In the chemical sector, we have lost about twelve plants in the past five years, including two major plants in Montreal and several plants in Ontario. Richard Paton, Canadian Chemical Producers’ Association, 7: 9:05 Industry officials were uneasy about the current economic recession and the decline in the industry’s production since the first quarter of 2009, but saw the current economic crisis as reason to focus policy matters on positioning the industry for future growth. The industry was clear about what it expects of governments: Industries like ours do not favour subsidies, handouts, or even special treatment, but we expect governments to do their part by creating the policy environment required for manufacturers to compete globally and by avoiding the introduction of measures that undermine or reduce competitiveness. We need policies that encourage investment in manufacturing and upgrading resources that stimulate progress toward sustainability objectives, which we believe is integral to that. Richard Paton, Canadian Chemical Producers’ Association, 7: 9:15 More specifically, the witness from the industry asked for three policy improvements of the federal government:

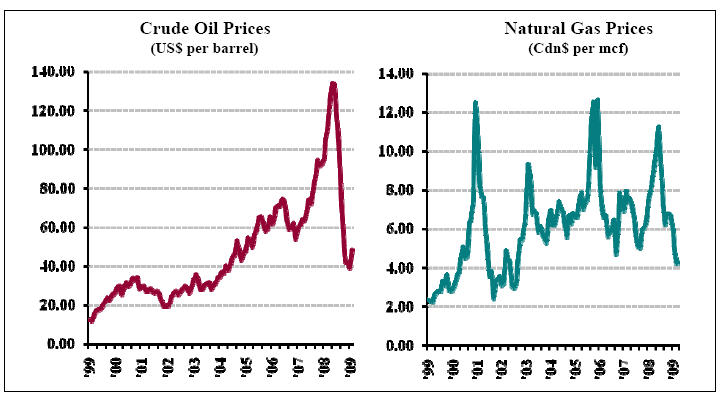

Canada is the world’s third largest producer of natural gas and ninth largest producer of crude oil. The industry puts a strong focus on exploration and development since only half of the country’s resource base has been exploited. Most of Canada’s oil and natural gas production is concentrated in the Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin, which has a mature onshore industry. Offshore petroleum activity is mainly in the Atlantic region, where approximately 18% of the country’s remaining petroleum resources are located. In 2008, Canada produced 429,000 cubic metres per day (m³/d) and exported 285,000 m³/d of crude oil. Natural gas production and exports were 458 and 282 million m³/d, respectively, with the vast majority of exports destined for the United States.[23] Canada’s oil sector has gone through some consolidation in recent years. Imperial Oil, majority owned by ExxonMobil, is the largest integrated oil and gas operator in the country. EnCana, formed from the merger of the Alberta Energy Company and PanCanadian Energy, is the largest independent upstream oil and gas operator in Canada. Other sizeable oil producers include Talisman Energy, Suncor, EOG Resources, Husky Energy, and Apache Canada.[24] In addition, there are about 400 small and medium-sized independent oil and gas exploration and production companies, including suppliers of products and services. A typical junior oil and gas company in Canada has fewer than a dozen employees, specializing in geo-science, engineering and finance. Most junior companies concentrate their activities on conventional oil and gas exploration and development in western Canada. However, there is a growing move towards unconventional resources such as oil sands and shale gas. The junior sector is 70% weighted towards natural gas production and it contributes about 25% of the dollars spent on Canada’s exploration, development, drilling and production. It also carries out approximately 60% of higher-risk exploration drilling in Canada.[25] The current economic slowdown has created financial instability in the market and reduced the global demand for oil and natural gas. In the words of one industry representative: The recession has hit the Canadian oil and gas industry where we do business. We provide the energy to fuel factories, heat homes, and let people drive their cars. The slowdown in economic activity means our customer, the world, is cutting back and using less of what we produce. When the world buys less, the price goes down. We all know how the price has dropped ... from a record high of $147 a barrel last summer to lows in the $35 a barrel range a few weeks ago. Don Daly, Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers, 9: 9:20 Natural gas producers have been more adversely affected than crude oil producers by the economic recession: Gas was at more than $11 per thousand cubic feet last June; today it trades at a little more than $3. With this unprecedented drop in prices, we’ve gone from being a $150-billion a year industry back in 2008, just last year, to about an $80-billion a year industry today. Don Daly, Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers, 9: 9:20 Figure 11

Source: Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers. It was reported that declining commodity prices reduced cash flows by as much as 75% in the past year.[26] But declining prices have further ramifications on financing: declining prices mean declining oil and gas reserve values, which reduce the available financing from banks. Investment levels are also down by one-third from 2008.[27] Consequently, about 20,000 of the industry’s workers are currently unemployed.[28] Crude oil prices have since recovered somewhat and the Committee was told that, at US$50 per barrel, this price was insufficient to get many new projects “off the ground”.[29] Many large projects (e.g., oil sands construction) have been deferred and this deferral is adversely affecting employment across the country, including the manufacturing sector where oil facility components are often made and assembled. It was further suggested that Canada’s oil sands projects require crude oil prices in the range of $60 to $75 per barrel for economic viability.[30] Looking beyond the industry’s immediate future, experts were generally optimistic: Tight capital markets remain a concern. ... [However,] the future resource potential remains strong, and industry continues to be optimistic about achieving this potential. But one thing is very clear: technology has been, and will continue to be, the key to unlocking that future. Technology has been the cornerstone of the oil and gas industry. Don Daly, Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers, 9: 9:30 But the witnesses expressed a number of structural challenges that increase operating costs within the oil and gas industry:

Witnesses from the industry asked for three policy improvements of the federal government:

Canada’s forestry industry generates $29.3 billion in GDP and provides over 250,000 jobs in communities across the country.[37] In the western provinces, the industry produces primarily wood products (i.e., lumber) while in central and eastern Canada forestry output is divided between softwood lumber and pulp and paper production. British Columbia, Quebec and Ontario are the largest producers by value of production at $8.8 billion, $7.9 billion and $6.6 billion, respectively. New Brunswick is the province most heavily dependent on the forest industry, which accounts for 7.4% of its GDP. It is followed by British Columbia at 5.9% of GDP and Quebec at 2.8% of GDP. The vast majority of the industry is located in rural and remote areas. Over 300 communities in Canada are dependent on the forestry sector, whereby dependence is defined as having at least 50% of wages earned in the community coming from forestry jobs.[38] Table 6

Source: Natural Resources Canada, http://canadaforests.nrcan.gc.ca/articletrend/top_suj/23. Canada is the world’s largest exporter of forestry products and the United States is its largest market, accounting for over three-quarters of its exports.[39] However, the industry has been in decline for the past six years. Between January 2003 and June 2008, 38,428 forestry workers lost their jobs, 90 mills closed permanently and 117 were indefinitely idled (see Table 6).[40] Every province in the country has experienced forestry job losses and all but one has experienced mill closures. The reasons for the decline are numerous. On the pulp and paper side, the precipitous drop in newspaper readership and advertising sales has been hard on this market segment.[41] On the lumber side, housing starts have declined sharply since the United States real estate bubble burst. American housing starts are down by over 75% from their peak in the second quarter of 2005[42] and Canadian housing starts are off by 9% from their peak in the first quarter of 2006.[43] The industry on the B.C. Coast describes this event and its response in the following way: Over the last two and a half years, as we saw the emergence of the subprime mortgage crisis and the beginning sharp decline in U.S. housing starts, as an industry we began to shift away from the U.S. market and away from commodity-based dimension lumber into those markets. ... In 2008 we increased our shipments to China, Korea, and other Asian countries from about 6% to 17%. ... From a lumber perspective, our dimension lumber production dropped from what would have been normally about 30% down to 13%, and the increases in other market segments were to the cedar market, to the shop remanufactured, specialty custom-cut markets. R.M. Jeffrey, Coast Forest Products Association, 5: 9:05 The industry has also had to close many mills to bring supply back in line with declining demand: [W]e have 2.5 billion board feet of capacity, and we are now currently running at 1.284 billion in 2008. That number will be under a billion board feet for 2009. R.M. Jeffrey, Coast Forest Products Association, 5: 9:05 For other industry segments, however, responses or solutions to problems are harder to come by: We are in a context of change, where for several years now we have seen a falling demand for newsprint, particularly because of increased Internet use. The softwood lumber dispute with the United States has reduced the demand for Canadian lumber. The current financial crisis is only prolonging and worsening the difficulties we are experiencing in the forestry sector. ... Because we are very specialized lumber harvesting subcontractors, it is harder for us to find other opportunities for our companies. Jacques Dionne, Association des propriétaires de machinerie forestière du Québec Inc., 5: 9:15 Yet the industry, in general, realizes that market diversification provides at the very least a partial response to the current economic dilemma: [T]he variety of our basket of products will count for a great deal in future. The more we diversify our products, the more we’ll be able to export internationally. Not being a prisoner of a single market like the United States would no doubt be a major advantage for the Canadian Industry. Guy Chevrette, Quebec Forest Industry Council, 2: 10:15 The sharp appreciation in the Canadian dollar between 2003 and 2007 greatly increased the price of Canadian forestry products in international markets. The dollar has subsequently depreciated, but industry representatives say that it will take some time for lost customers to return. The Forest Products Association of Canada (FPAC) claims that high transportation costs are taking a toll on its members. Approximately 70% of forestry products are shipped by rail and the FPAC estimates that uncompetitive freight prices cost the industry $280 million a year.[44] The Mountain Pine Beatle epidemic in British Columbia has temporarily increased harvests in the province, as companies rush to harvest trees before they are destroyed. The epidemic will, however, mean lower harvests in the region over the medium and longer term. Finally, some industry analysts say that producers have failed to modernize their mills and equipment and sufficiently invest in research and development. According to the FPAC, the industry’s capital stock is, on the whole, older and less productive than that of its international competitors.[45] FPAC was succinct on both the benefits and limitations of federal government assistance: Clearly, you [the government] can’t increase demand for newsprint or raise lumber prices — we have to wait for markets to do that — but you can help us get from here to the return of markets. The government has made a lot of the right moves in EI work sharing, which is keeping many mills open that would have otherwise closed. The announcements to EDC changes and new funding for debt are very positive. Avrim Lazar, Forest Products Association of Canada, 2: 9:05 The industry was also unequivocal on what its primary issue was and how the federal government might be of further help: Our member companies have identified access to credit and reasonably priced credit as a top issue to be addressed. ... [T]he forest industry [has] been considered high risk now for several years, and this has definitely added to the challenge. ... In the rare chance that an investor makes capital available to our industry, the industry faces ridiculously high risk premiums — premiums from 8% to 11%, which make it virtually impossible to survive. Mark Arsenault, New Brunswick Forest Products Association, 5: 9:25 At the same time, a number of industry representatives identified a role to play for the federal government in resolving and/or responding to tax subsidies recently provided by the U.S. government to its pulp and paper industry. Under recently devised renewable energy initiatives, U.S. pulp and paper mills are eligible for substantial tax credits for burning “black liquor” along with diesel fuel in their boilers. U.S. pulp and paper companies are eligible for a 50¢ per gallon excise tax credit on the use of concentrated pulping liquors, the residual waste that is created from the pulping process. Estimates put the value of that credit at $125 to $150 per tonne for unbleached mills, and $175 to $225 per tonne for bleached mills. This has created a very unlevel playing field: These credits put Canada at a serious disadvantage. I believe if it’s unaddressed, this may be catastrophic to our pulp mills on the Canadian side of the border. ... if a bleached hardwood market kraft mill can actually realize a benefit of $175 per tonne, it will put the cost structure of our Canadian mills at a huge disadvantage. Mark Arsenault, New Brunswick Forest Products Association, 5: 9:30 A number of industry representatives highlighted the need for sylvicultural financing and investment. For example, one industry representative also suggested that the federal government consider creating a sylvicultural savings plan that would enable forest owners to accumulate tax sheltered funds that could be used for the development of woodlots. To meet both its cyclical and structural challenges, witnesses from the industry asked for five policy improvements of the federal government:

The high technology sector is made up of industries that make/create technology, whether the technology is in the form of products, communications, or services.[46] Although innovative activities can be found in many industries, this definition includes only those industries where high technology activity is concentrated. High-tech industries are the product of the rapidly evolving global environment of science, technology and innovation. The information and communications technologies (ICT) sector is a striking example of the shift of our economy into a new era, the digital economy. The emergence of biotechnology companies also points to a new high tech sector, the bio-economy. A. Information and Communications Technologies The ICT sector is increasingly important in the economy. Just 30 years ago, the telephone was the most widespread communication technology. Nowadays the influence of ICTs is felt in all aspects of life. In the late 1990s, there was impressive growth in the ICT sector, which became one of the key drivers of national growth. Even since the technology bubble burst in the early 2000s, the ICT sector GDP has grown faster than that of the entire Canadian economy (see Figure 12). In 2008, the ICT sector GDP was $59.2 billion, with annual growth of 4.8%.[47] Changes followed the decline in 2000, symbolized by plummeting stock prices on the NASDAQ high technology exchange. Revenues from ICT manufacturing fell while revenues from services increased greatly. A total of 30,300 ICT companies in Canada generated total revenues of $150 billion in 2007. A bit less than half of that revenue came from the ICT wholesaling and manufacturing subsectors, and 56% came from the subsector made up of telecommunications services, software and informatics services, cable television and other ICT services.[48] Figure 12

Source: Industry Canada, Information and Communications Technologies Statistical Overview, April 2009. In 2007, the ICT sector accounted for about 3.5% of workers in Canada, with 592,600 employees, 43% of whom had a university degree, as compared to 24% of workers in Canada in general.[49] This dynamic sector, therefore, has a highly educated workforce. The sector also accounts for 38% of private sector R&D in Canada, with R&D spending that has been rising since 2002, reaching $6.0 billion 2007. Companies in the ICT sector are relatively small. In 2007, four out of five companies had less than 10 employees and just one in 50 companies had more than 100. A number of them, such as Cisco and CGI, have experienced so much growth in recent decades that they are internationally known. Others such as Nortel have developed a whole “ecosystem” of small regional companies that revolve around it. Although the ICT sector has undeniably matured, it is in a slowdown as a result of the current global recession, and financing is its greatest worry: What we have during the current crisis, however, is things have fallen off a cliff, so you're not even there at some point. We have very successful companies that actually have sales, have extraordinary, major clients, and all of a sudden they cannot get money. They have very successful business plans, and things have just been disrupted at this point, beyond normal. Bernard Courtois, Information Technology Association of Canada, 10 : 10:40 Biotechnology is a young sector that has seen especially rapid growth in the past decade. Biotechnology has a variety of branches that affect our lives in many ways and that are now part of the “bio-economy”. The value of this bio-economy is estimated at $78 billion per year, or 6.4% of Canada’s GDP, and includes the subsectors of health, cattle and truck farming, mining bio-processing, pharmaceutical manufacturing, chemical products and distilleries.[50] With respect to innovative biotechnology companies, their numbers nearly doubled between 1997 and 2005, rising from 282 to 532.[51] In 2005, biotechnology revenues were $4.2 billion and R&D expenditures, some of which are publicly funded,[52] totalled $1.7 billion. Biotechnology companies report biotechnology products and processes in the thousands: in 2003, for instance, 5,000 products and processes were at the R&D stage and there were over 11,000 on the market. Biotechnology clusters are concentrated in 20 or so cities across Canada in relatively populous regions.[53] In 2005, the biotechnology sector employed 13,433 people in Canada. The results of a survey presented by BIOTECanada[54] show that a quarter of companies will be short of funds within six months, that half of companies will disappear by the end of 2009 and that companies are limiting their activities to survive. The financial crisis has had a significant impact on biotechnology companies and hence on the pursuit of innovation in biotechnology. The total capital obtained by biotechnology companies fell by 41% from 2007 to 2008.[55] A single initial public offering (IPO) in biotechnology was identified in 2008 with a value of $5.8 million, as compared to 28 IPOs that raised $1.7 billion in 2007. In October and November 2008, 13 Canadian biotechnology companies ceased operations, either closing their doors or going bankrupt. Certain major initiatives were shelved and the same could happen to a number of pharmaceutical initiatives at the clinical trial stage. Some companies are vulnerable to takeovers and acquisitions that would export intellectual property developed in Canada to foreign competitors. We can’t afford to have the industry decimated by the credit crisis. Too much has been built into these operations to get them into a commercialization cycle … These jobs are very portable … In the world of R&D, we run the risk of just simply exporting our IP like we’ve exported raw natural resources in the past. Our goal is to make sure that we create an environment, that we capture that value in Canada. Peter Brenders, BIOTECanada, 10: 9:15 The financing problems resulting in part from the lack of venture capital in Canada are now also affecting ICT and biotechnology industries, which are hoping that appropriate measures will build on their key success factors — factors such as quick access to funding, tax incentives and talented employees. High tech companies have stressed the importance of building stronger ties with U.S. venture capital investors, but there are impediments that have limited the entry of foreign capital into Canada. [T]he Canadian venture capital pool is always going to be too thin and not as experienced and mature as what can come from the US. Those investors bring more than money. They bring management experience; they bring experience on how to scale the company. I know, for example, that Israel has a policy of actually encouraging their companies to get their capital from outside the country because they know that they have the science but that they don’t have the global marketing and business development that comes with it. Bernard Courtois, Information Technology Association of Canada, 10: 9:35 As such, biotechnology companies are in favour of clarifying the application of recent changes to section 116 of the Income Tax Act so that they can increase their access to U.S. venture capital. We saw great movement in terms of changing the Canada-US tax treaty in terms of recognition of limited liability companies. The problem is that we’re still sitting on an administrative detail called the “116 Certificate”, which requires a host of signatures that just can’t be done. … That needs to be fixed. Peter Brenders, BIOTECanada, 10: 9:35 Although high tech companies are strong in developing technology, they could benefit from enhancing their commercialization activities. Intellectual property issues pertaining to the Copyright Act, technology transfer (following the University of Waterloo model, for instance) and data security were also raised. Despite these concerns, there is unanimous support in the high tech sector for the creation of value and capitalizing on technology and innovation as a path to success. Industry representatives praised the government for its Advantage Canada strategy and its SR&ED tax credit program that they characterized as far more generous than similar programs in other countries. They also had positive comments to make on elements of the government’s recent budget: On the whole issue of knowledge infrastructure, I want to commend the government for recognizing in its February 2009 budget that infrastructure goes beyond bricks and mortar to putting broadband, that we’ve talked about, which looks like a civil engineering project, but it’s obviously an economic enabler. … the electronic health record, the electronic medical record, may look like an IT project, but it’s not really. It’s a fundamental infrastructure to run a modern health care system. Bernard Courtois, Information Technology Association of Canada, 10: 10:45 Witnesses from the high tech sector asked for seven improvements from the federal government to meet current and future challenges:

The minerals and metals industry contributed $42 billion to Canada’s GDP in 2007, including $10 billion in mineral extraction and $32 billion in mineral processing and manufacturing. In 2007, the industry employed 363,000 Canadians, including 51,000 in mineral extraction, 55,000 in non-metal manufacturing, 79,000 in primary metal fabrication, and 179,000 in fabricated metal manufacturing.[56] Canada is one of the largest mining nations in the world, with 222 active mines producing more than 60 minerals and metals. These mines are located in all regions of the country. Indeed, most mining communities are located in rural and northern regions of the country, and given that these mines are located in the vicinity of more than 1,200 Aboriginal communities, they are significant employers of Aboriginal peoples.[57] Canada also has a relatively large mineral processing industry, with 38 nonferrous metal smelters and refineries operating in six provinces (see Table 7). Table 7

Source: Mining Association of Canada, Facts & Figures 2008: A Report on the State of the Canadian Mining Industry, 2009. Canadian mining companies are often multinational in activity. Canadian-listed companies have interest in more than 8,000 exploration and mining properties in more than 100 countries.[58] The Mining Association of Canada reports that there are 3,034 Canadian firms that provide various expertise to the industry, including:

Although the industry is very visible in many small and remote communities across Canada, it also contributes to the economy of Canada’s largest cities. Toronto is the world’s leading city for financing mining activities. The Toronto Stock Exchange handled 80% of worldwide mining equity transactions in 2007.[60] The mining industry in Canada is coping with the current downturn in the world economy, something it does periodically given the industry’s cyclical nature: In terms of the present situation, companies are adjusting to mineral prices. One of their fundamental roles is to adjust operations to reflect mineral prices. These prices are generally global prices and they’re derived through international trading exchanges. ... Some countries in particular have been managing their debt loads ... to ensure their future prosperity. Paul Stothart, Mining Association of Canada, 10: 11:00 Unlike many other industries that are focused almost entirely on manufacturing activities, the Canadian minerals and metals industry does not face a new and strong foreign competitor in China with its accession to the World Trade Organization in 2001. China’s presence in the international market is mostly felt on the demand side ... and it’s a favourable influence: The main effect of China is as a driver of mineral prices. Most of our mineral exports still go to the U.S., but the prices are driven globally by Chinese demand. .... Obviously with higher prices, everybody from companies to employees make more money. Paul Stothart, Mining Association of Canada, 10: 11:20 Industry representatives identified a number of challenging structural issues that the industry must contend with: (1) declining mineral reserves; (2) human resource problems that are driven by demographic factors and industry perceptions; (3) environmental regulation and policy; and (4) the need for more national cooperation and collaboration. Canada’s reserves of base and precious metals have declined significantly over the past quarter-century. The most dramatic decline in reserves occurred in lead, zinc, molybdenum and silver; they declined by more than 80% between 1980 and 2005. Copper and nickel reserves declined by more than half in this period and, in 2005, gold reserves were one-third lower than a decade earlier (see Table 8). An industry representative expounded on this issue: Mineral reserves are an issue for this industry. Canada’s proven and probable reserves of base metals and some others have gone down over the last quarter century so there’s a need to reverse that. Paul Stothart, Mining Association of Canada, 10: 10:55 Table 8

Note: t = metric tonne. Source: Mining Association of Canada, Facts & Figures 2008: A Report on the State of the Canadian Mining Industry, 2009. A representative from the Mining Association of Canada argued that unless new and effective exploration is undertaken, Canadian reserves of key minerals will remain at critically low levels and thereby weaken the case for investing in value-added facilities. Moreover, without sustained and effective exploration, production will continue to outstrip reserve additions, Canadian smelters and refiners will be forced to increasingly rely on imported raw materials, and Canada’s mineral and metals industry could be put in a position of heightened competitive and strategic risk. The representative further stated that federal and provincial government investment in geo-science has declined by one-half since 1988, with the result that important Canadian regions remain poorly mapped. The industry also faces a significant human resource challenge in the coming decade. As one industry representative put it: A ... challenge is attracting new people ... [the] mining industry has a demographics problem. The young people don’t go into mining-oriented courses when things are down; they go in when things are up. When they come out, there are no jobs ... Jon Baird, Canadian Association of Mining Equipment and Services for Export, 10: 11:05 It is estimated that approximately 65% of geoscientists will reach retirement age (i.e., 65 years) in the next decade and that the industry will need between 60,000 and 90,000 new workers by 2017.[61] Moreover, the human resources recruitment challenge is more acute than these basic statistics suggest because the demographics problem is more pronounced for the mining industry than for other industries, as it traditionally attracts fewer females, youth and minorities. Representatives from the mining industry also suggested that the Canadian mining industry is too fragmented: The mining industry is quite fragmented ... We don’t have a sense of national purpose. Control over resources is a state [provincial] matter as it is in this country. That’s where I think our balkanization starts. Jon Baird, Canadian Association of Mining Equipment and Services for Export, 10: 11:50 I think a national mining strategy to the extent that incorporated R&D components and infrastructure components, incentives for more value added and for more modern processing facilities might be worth considering. Paul Stothart, Mining Association of Canada, 10: 11:50 Despite these challenges, industry representatives are generally positive about the industry’s long-term future. They mentioned that the market potential of China is staggering. Currently, there are about two cars per 100 persons in China, whereas there are about 95 cars per 100 persons in the United States and it is believed that this gap will narrow. Both China and India are moving towards more feed-intensive, protein-based diets which bodes well for Canadian potash sales. China is investing in nuclear power and this bodes well for Canadian uranium sales. As the middle-class grows throughout the world, it is believed that there will be more demand for gold, diamonds and other precious metals.[62] The industry is also experiencing a decline in its input costs since the global recession set in. Industry representatives further claim that the Canadian mining industry receives reasonably competitive tax treatment in Canada. Moreover, this treatment will improve further as the corporate income tax rate is scheduled to decline to 15% by 2012. However, an industry official suggested that the tax treatment accorded to investments in mineral exploration at depth within existing underground workings could be improved. The industry was also very favourable to the notion and policy of free trade, particularly encouraging has been the Government of Canada’s focus on Foreign Investment Protection Agreements (FIPAs): FIPAs ... are useful even if they’re not used that much. They provide some guidance to foreign countries, and they provide some comfort to companies who are investing in these countries that if there is a dispute, they will have some independent arbitrator and some independent rules through which they can regulate that dispute. Paul Stothart, Mining Association of Canada, 10: 12:05 To meet its ongoing structural challenges, witnesses from the industry asked for eight policy improvements of the federal government:

Railroad rolling stock manufacturing make up part of the transportation equipment manufacturing subsector (Canada’s largest manufacturing subsector). Railroad rolling stock companies design and manufacture equipment such as: ballast distributors (railway track equipment); self-propelled railroad cars; diesel-electric locomotives; railway track equipment (e.g., rail layers, ballast distributors); mining locomotives and parts; railway rapid transit cars; rail laying and tamping equipment; subway cars; and trolley buses. The rail equipment manufacturing sector is highly specialized and export-oriented, with more than 70% of urban transit and locomotive shipments destined for foreign countries, principally the United States. Virtually all Canadian urban transit and rail systems and vehicles are supplied by domestic sources, while major systems and components such as engines, computers and other equipment are usually imported from U.S. suppliers. The Canadian Association of Railway Suppliers (CARS) represents more than 400 of these companies with annual domestic sales of $4 billion. In addition, more than 300 of these companies generate export sales totalling $5 billion, making the total output of the industry more than $9 billion per year. Railway supply companies employ more than 60,000 Canadians. Railway equipment suppliers have committed themselves to long-term transformative change that would make significant reductions in harmful emissions through new and innovative emissions-reducing technologies. The industry believes it can help the Canadian government meet its environmental targets. With this goal in mind, CARS suggested that the time is right for upgrading Canada’s railway sector: There are 300 locomotives parked right now. They’ve been taken out of service. There are over 20,000 freight cars out of service right now. If we’re ever to upgrade, this is an ideal time to do it. Jay Nordenstrom, Canadian Association of Railway Suppliers, 7: 9:30 CARS further requested that the federal government:

[16] The source of these data is Industry Canada, “Pursuing Excellence — Canada’s Aerospace Sector,” September 2008. [17] Canadian Chemical Producers’ Association, “The Competitiveness of Canada’s Business and Policy Environment for Chemical Producers,” 2008-2009. [18] The Chemical Industry, http://chemicalengineering.dal.ca/Files/2_-_The_Chemical_Industry.ppt [19] Industry Canada, http://www.ic.gc.ca/cis-sic/cis-sic.nsf/IDE/cis325cste.html. [20] Canadian Chemical Producers’ Association, Business and Economic Issues, http://www.ccpa.ca/files/Library/Reports/KeystoneDocs/Toronto.pdf. [21] Ibid. [22] The House of Commons Standing Committee on Industry, Science and Technology made the following recommendation: That the Government of Canada improve the SR&ED Tax Incentive Program to make it more accessible and relevant to Canadian businesses. The government should consider making the following changes:

Finance Canada estimated that, excluding the proposal to extend the tax credit to cover these other activities, the fiscal cost of implementing the above SR&ED measures would vary from $8.2 billion to $16.2 billion over five years. [23] Canadian Energy Overview 2008, May 2009. National Energy Board [online]: http://www.neb.gc.ca/clf-nsi/rnrgynfmtn/nrgyrprt/nrgyvrvw/cndnnrgyvrvw2008/cndnnrgyvrvw2008-eng.html#s5. [24] Canadian Technology in the Oil and Gas Industry, Industry Canada [online]: http://www.ic.gc.ca/eic/site/ogt-ipg.nsf/eng/dk00057.html. [25] Gary Leach, Small Explorers and Producers Association of Canada, Committee Evidence [9: 9:30], May 5, 2009. [26] Gary Leach, Small Explorers and Producers Association of Canada, Committee Evidence [9: 10:15], May 5, 2009. [27] Gary Leach, Small Explorers and Producers Association of Canada, Committee Evidence [9: 10:15], May 5, 2009. [28] Don Herring, Canadian Association of Oilwell Drilling Contractors, Committee Evidence [9: 10:25], May 5, 2009. [29] The Committee notes that upon the writing of this report, West Texas Intermediate crude oil, the North American benchmark price, is selling for more than US$61 per barrel. [30] David Daly, Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers, Committee Evidence [9: 10:50], May 5, 2009. [31] Don Herring, Canadian Association of Oilwell Drilling Contractors, Committee Evidence [9: 9:05], May 5, 2009. [32] Gary Leach, Small Explorers and Producers Association of Canada, Committee Evidence [9: 9:30], May 5, 2009. [33] David Daly, Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers, Committee Evidence [9: 9:45], May 5, 2009. [34] Gary Leach, Small Explorers and Producers Association of Canada, Committee Evidence [9: 9:30], May 5, 2009. [35] Gary Leach, Small Explorers and Producers Association of Canada, Committee Evidence [9: 10:45], May 5, 2009. [36] Effective January 1, 2007, Transport Canada passed a regulation to govern oil and gas activities based on the number of hours worked by drivers and daily documentation is already produced by the industry and is used as a measuring tool. [37] The forestry industry includes logging, sawmills and pulp and paper manufacturing. All data in this paragraph is for the year 2007, the latest year for which data is available. Source: Statistics Canada CANSIM Series 379-0025 and 281-0024. [38] Natural Resources Canada, “Forest Communities: Weathering Economic Change,” http://canadaforests.nrcan.gc.ca/articletopic/183, August 12, 2008. [39] Natural Resources Canada, “Trade data,” http://canadaforests.nrcan.gc.ca/statsprofile/trade. [40] Natural Resources Canada, “Forest-dependent Communities in Canada,” http://canadaforests.nrcan.gc.ca/articletrend/top_suj/23, August 8, 2008. [41] The Audit Bureau of Circulations reports that American newspaper circulation decreased by 7% in the October 2008-March 2009 period compared with the same period one year earlier. Source: Robert MacMillan, “U.S. newspaper circulation declines worsen,” Reuters, April 27, 2009. [42] U.S. Census Bureau, “New Residential Construction,” http://www.census.gov/const/www/newresconstindex.html. [43] Statistics Canada, CANSIM Table 027-0007. [44] Forest Products Association of Canada, “An Estimate of the Freight Rate Consequences of Rail Captivity to Rail Shippers of Canadian Forest Products,” prepared by Travacon Research Limited, April, 2007. [45] Forest Products Association of Canada, “Industry at a Crossroads: Choosing the Path to Renewal, Report of the Forest Products Industry Competitiveness Task Force,” May 2007. [46] See definition of “high technology,” which has been used or adapted by many institutions around the world, in Platzer, M., Novak, C.A. and Kazmierczak, M.F. Defining the High tech Industry. American Electronics Association, February 2003, http://www.aeanet.org/Publications/idmk_naics_pdf.asp. [47] Industry Canada, Information and Communications Technologies Statistical Overview, April 2009, http://www.ic.gc.ca/eic/site/ict-tic.nsf/eng/h_it05864.html. [49] Industry Canada, Information and Communications Technologies Statistical Overview, November 2008, http://www.ic.gc.ca/eic/site/ict-tic.nsf/vwapj/0107229e.pdf/$FILE/0107229e.pdf. [50] The figures cited here are used by BIOTECanada and were published in “Measuring the Biobased Economy: A Canadian Perspective,” in Industrial Biotechnology, Winter 2008 (vol.4, no.4, pp.363-366), The Feature Commentary by William Pellerin and D. Wayne Taylor. [51] Statistics Canada. Innovation Analysis Bulletin, 2008, No.88-003-X, Vol. 10, no. 2; and Canadian Trends in Biotechnology, Second Edition, p 16, based on data from the Biotechnology Use and Development Survey, various years. [52] OECD Biotechnology Statistics, 2006, p. 19. According to this report, federal spending on biotechnology R&D amounted to 31.5% of private sector biotechnology R&D expenditures. [53] Industry Canada. Biotechnology Clusters, http://www.ic.gc.ca/eic/site/cbc-gccb.nsf/eng/h_bq00009.html. [54] BIOTECanada. “Biotechnology crucial to future economic prosperity and Canadians agree!”, Situational Analysis: Biotech Industry, January 9, 2009. [55] BIOTECanada, Situational Analysis, January 9, 2009 (source: Thomson Reuters). [56] Mining Association of Canada, Facts and Figures 2008: A Report on the State of the Canadian Mining Industry, 2009. [57] Natural Resources Canada, Canada’s Minerals and Metals Key Facts, 2009. [58] Ibid., p. 1. [59] Mining Association of Canada, Op. Cit., 2009. [60]. Ibid. [61] Paul Stothart, Mining Association of Canada, Committee Evidence [10:10:55], May 14, 2009. [62] Paul Stothart, Mining Association of Canada, Committee Evidence [10:11:00], May 14, 2009. |