LANG Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

3. Immigration

“Now, I think it is time to deliver the goods.”[107]

Like the health sector, immigration was identified as a priority in order to foster the vitality of official language minority communities. Since the demographic growth of communities is the ultimate factor in their vitality, it is clear that the birth rate alone will not be sufficient to offset the decline in the number of families that speak French at home outside Quebec, and that speak English at home in Quebec. This is true for Canada’s population as a whole, but is essential to the long-term survival of official language minority communities. It is especially true for Francophone communities outside Quebec. Despite the explicit priority given to French-language immigrants in Quebec legislation, the Anglophone community of Quebec, with its quality institutions and economic and cultural strength, is much more attractive than Francophone minority communities, which must first make potential immigrants aware of their existence before they can attract anyone at all. There are of course differences for Anglophone communities outside Montreal that are in a comparable position and must for instance try to retain students from other provinces who have a choice to remain in Quebec or leave.[108]

Similarly, the retention of families depends on the vitality of community life, and attracting newcomers depends on them receiving a warm reception. A family or individual may be willing to make sacrifices in terms of occupational or economic rewards if they feel attached to the community. Without this kind of attachment, the children will go to English-language schools, assuming equal economic prospects. Once again, success depends on the ability of community networks to welcome and integrate newcomers. The second condition, as we will see later on, is the active involvement of the provincial government. If the provincial government does not recognize the benefits of stimulating immigration among these Francophone communities, it is unlikely that federal investments will produce results. The proactive strategy of some provincial governments, especially Manitoba, is a prime example of the need for this kind of collaboration among the partners in the Canadian federation.

In some Francophone communities in Canada, especially in large cities, immigration has already become commonplace. The clientele of the Centre francophone de Toronto, for instance, consists primarily of newcomers.[109] Vancouver’s French-language school board serves students from 72 different countries who speak 58 languages in addition to French.[110]

Including an “Immigration” sub-component in the “Community Life” component of the Action Plan for Official Languages was certainly one of the first clear signs of the federal government’s intention to use this development tool. This step was in response to the community consultations conducted by the Fédération des communautés francophones et acadiennes du Canada, work that was also supported by studies coordinated by the Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages, to which we will refer briefly below.

It must be noted first of all that the Action Plan’s investment is modest at $9 million over five years; it appears to have mobilized the communities somewhat, but its results cannot be measured for the time being.[111] It can be said that the support for immigration thus far has been a small step rather than a real strategy.[112] This is why the Committee was delighted by the federal government’s launch in September 2006 of the Strategic Plan to Foster Immigration to Minority Francophone Communities. We will consider later on whether this plan has the consistency and flexibility needed to achieve its ambitious objectives.

This section outlines what we know about Francophone immigration to Canada. It then reviews the various elements of the federal plan designed to foster Francophone immigration. Finally, it presents the testimony heard by the Committee regarding the success of various initiatives to date, the persistent shortcomings and the potential ways of using immigration to strengthen community vitality in more than an anecdotal way.

3.1. Knowledge of Francophone immigration to minority communities

The Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages has published two studies on immigration to Francophone minority communities, but their analysis is controversial and the Strategic Plan to Foster Immigration to Minority Francophone Communities did not include their results.[113] The Steering Committee mandated by Citizenship and Immigration Canada to prepare this strategic plan did however use a study by the Fédération des communautés francophones et acadiennes du Canada (FCFA).[114] This study provides a demographic profile of Francophone immigration to Canada from 1981 to 1996. It does not indicate the retention of Francophone immigrants in Francophone minority communities or their mobility, although it could serve as a starting point.

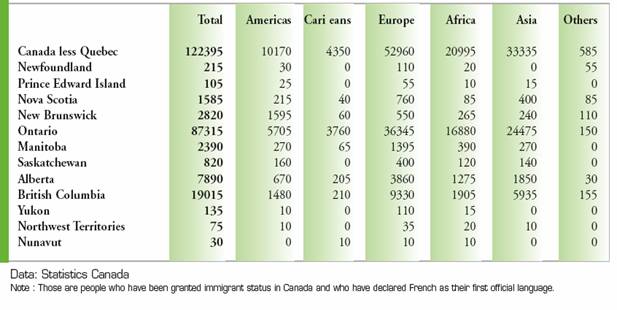

Based on the 2001 census data, as compiled by the Fédération des communautés francophones et acadiennes du Canada, 122,395 immigrants, whose first official spoken language is French, settled outside Quebec, or 12.4% of all Francophones outside Quebec. This proportion was 16.5% for Ontario, the province where close to three-quarters of all these immigrants settled, and 32.0% in British Columbia, where close to 20,000 Francophone immigrants settled.

Number of Francophone Immigrants, 2001, provinces and territories

Jean–Pierre Corbeil of Statistics Canada paints a much less positive picture: “As for the surveys conducted by Statistics Canada on French-speaking immigrants, we are really at square one.”[115] He also questions the above figures, and cuts in half the number of Francophone immigrants who settled outside Quebec:

Statistics drawn from the 2001 census show that using the first official language spoken criteria, there were some 53,000 French-speaking immigrants outside Quebec or slightly more than 1% of the immigrant population. For the non-immigrant population, the proportion is 5%. Bear in mind that these 53,000 immigrants whose first official language spoken is French live, for the most part in Toronto and Ottawa, where the respective number fluctuates around 11,000. What’s more, in addition to these 53,000 immigrants whose first official language spoken is French, there are about 70,000 immigrants for whom we cannot determine whether English or French is their first official language spoken. Therefore, Statistics Canada created a residual category called “first official language spoken English-French”. Using information provided in response to the question on the other languages spoken on a regular basis in the home, we did note, however, that a large proportion of these immigrants tend to favour English over French, even if they indicate that they have some knowledge of both official languages.[116]

3.2. The 2003-2008 Action Plan and the 2006 Strategic Plan

The Action Plan for Official Languages of 2003 included $9 million over five years for Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC) “to conduct market studies and design promotional materials for distribution abroad”[117] and to “support information centre projects for French-speaking immigrants and distance education French courses sensitive to newcomers’ needs.” It appears however that the funding allocated was used primarily to boost the bilingual capacity of federal bilingual agencies involved in immigrant reception and for the planning work of the Citizenship and Immigration Canada Steering Committee.[118]

On September 11, 2006, the Minister of Citizenship and Immigration, the Honourable Monte Solberg, and the Minister for International Cooperation, the Francophonie and Official Languages, the Honourable Josée Verner, jointly launched the Strategic Plan to Foster Immigration to Francophone Communities. This plan was produced by the Citizenship and Immigration Canada Steering Committee — Francophone Minority Communities (hereafter the Steering Committee).

According to the 2001 Census, Canadians living outside Quebec whose first official language spoken is French accounted for 4.4% of the population of Canada. The Plan is intended to balance out the current proportion of Francophones outside Quebec with “French-speaking” immigrants who settle outside Quebec every year. [119] The primary objective of the Plan is to achieve this annual proportion by 2008, through a variety of initiatives extending until 2011 in order to consolidate this growth. Considering that only about 1% of all immigrants to Canada have French as their first official language spoken and live outside Quebec, achieving this objective in 2008 would be a spectacular reversal.

3.2.1. History and Mandate of the Steering Committee

The Steering Committee was created in March 2002 further to the consultations of Francophone minority communities conducted between 1999 and 2001 by the Fédération des communautés francophones et acadiennes du Canada (FCFA). These consultations pointed to the potential of immigration to foster the vitality of Francophone communities and were supported by analyses by the Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages.[120]

The Steering Committee comprises ten CIC representatives from various branches and regional branches, from twelve federal departments, six provinces, one territory, one representative of the Francophone Intergovernmental Affairs Network and eleven community representatives. Its initial mandate was as follows:

§ To collaborate in developing a strategy to raise awareness of immigration issues in Francophone minority communities and to increase their reception capacity;

§ To collaborate in developing a strategy to raise awareness in employees, service providers and CIC clients within Canada and abroad in all matters related to Canada’s bilingual nature, the desired results in terms of immigration, and the presence of official-language minority communities in each province and territory, in order to increase immigrant settlement within Francophone minority communities;

§ To collaborate in developing a strategy to liaise with Francophone minority communities in order to promote their participation in CIC’s public activities and consultations, thereby increasing their expertise in immigration matters;

§ To collaborate in developing a promotion, recruitment and selection strategy in order to increase the number of immigrants who choose to settle in Francophone minority communities;

§ To participate in the implementation of a new strategy to integrate immigrants into Francophone minority communities;

§ To identify CIC priorities under the memorandum of understanding with Canadian Heritage for the implementation of the Interdepartmental Partnership with the Official Language Communities;

§ To commission studies and research on issues related to immigration within Francophone minority communities to ensure that strategies are developed;

§ Other activities deemed essential by Steering Committee members.[121]

In order to achieve concrete results with respect to the ”Immigration” sub-component of the Action Plan for Official Languages of 2003, the Steering Committee published in November 2003 the Strategic Framework to Foster Immigration to Francophone Minority Communities (hereafter Strategic Framework).[122]

The Strategic Framework of 2003 set out five objectives:

1. Increase the number of French-speaking immigrants to give more demographic weight to Francophone minority communities;

2. Improve the capacity of Francophone minority communities to receive Francophone newcomers and strengthen their reception and settlement infrastructures;

3. Ensure the economic integration of French-speaking immigrants into Canadian society and into Francophone minority communities in particular;

4. Ensure the social and cultural integration of French-speaking immigrants into Canadian society and into Francophone minority communities;

5. Foster regionalization of Francophone immigration outside Toronto and Vancouver.

A provisional assessment of the initiatives developed to achieve these objectives was published in March 2005 under the title, Towards Building a Canadian Francophonie of Tomorrow. Summary of Initiatives 2002-2006 to Foster Immigration to Francophone Minority Communities.[123] Despite these excellent initiatives, they were essentially short-term, one-time projects that did not last long enough to significantly increase the proportion of Francophone immigrants choosing to settle in minority communities.

It was to address this shortcoming that the Steering Committee developed the Strategic Plan, which includes the objectives set in 2003.

3.2.2. Content of the Strategic Plan

The Plan “more clearly identifies the challenges and issues to be addressed, proposes focused actions for the next five years and sets a course for the long term.”[124]

The first part of the Plan pertains to four challenges:

1. The number and make-up of French-speaking immigrants to FMCs;

2. Immigrant mobility;

3. Social and economic integration of immigrants;

4. FMCs’ lack of capacity to recruit, receive and integrate French-speaking immigrants.

The second part of the Plan addresses strategic choices, that is, the available options that the Steering Committee considers most likely to produce results if concrete action is taken. Suggested initiatives are outlined, as well as potential performance indicators for these initiatives. The link between the “strategic choices” and the “challenges” outlined in the previous point however is not defined.

The third part of the Plan summarizes the legislative and government policy framework, while the fourth part describes the strategy to implement the five-year plan in order to achieve the objectives. This five-year plan includes coordination mechanisms, priorities for action and financial considerations.

The local and provincial coordination mechanisms are left up to the communities. At the national level, the Steering Committee suggests that its mandate be renewed and that an Implementation Committee be added to it to turn the strategic Plan into concrete action.

The priorities for action for 2006 to 2011 are:

§ Implementing and supporting local networks;

§ Increasing the awareness of the local community;

§ Implementing language training in English and/or French;

§ Providing training to upgrade professional and employability skills;

§ Research;

§ Supporting the creation of micro-businesses;

§ Supporting French-language post-secondary institutions in the recruitment and integration of foreign students;

§ Promoting immigration and selecting potential immigrants;

§ Supporting refugees.

Various funding possibilities are suggested for these initiatives.

3.2.3. Shortcomings of the Plan

The Committee members support the objectives of the Strategic Plan and recognize that adopting an approach to foster Francophone immigration to minority communities represents progress. They would also like to see these objectives achieved and that all individuals and organizations involved in implementing the Plan are able to track progress. In its present form, however, the Plan contains various weaknesses that seriously undermine the attainment of its objectives. The most important weaknesses are as follows.

3.2.3.1. No Statement of Current Status

A strategic plan should identify a starting point, the desired outcome and the ways to achieve it under the existing circumstances. The Plan does not indicate the actual number of immigrants currently living in Francophone communities outside Quebec and simply repeats the fragmentary public data from Statistics Canada and Citizenship and Immigration Canada. The Steering Committee did not conduct or commission any special study. The Plan’s authors themselves conclude that: “Citizenship and Immigration Canada must improve its capacity to measure immigrants’ knowledge of Canada’s official languages in order to determine more precisely the changes in demographics for immigration to official language minority communities.”[125] This is a considerable weakness since setting targets also depends on the ability to identify the initial conditions.

The same criticism applies to the Plan’s data regarding immigrant mobility: if it is impossible to know where they are it is impossible to know where they are going. Given the limited data on their numbers and mobility, any measure to foster their social and economic integration will be based on very hypothetical analyses, if any. The information regarding communities’ ability to receive immigrants is more solid since a study conducted in 2004 by Prairie Research Associates for the FCFA[126] indicates the key aspects.

Appearing before the Committee, Jean–Pierre Corbeil from Statistics Canada indicated the best ways to address these shortcomings:

One of the major Statistics Canada surveys on the settlement of immigrants in Canada is the Longitudinal Survey of Immigrants to Canada […] Given the relatively small sample at the end of the third cycle, [it] does not, however, enable us to obtain reliable data on French-speaking immigrants outside Quebec. It is nevertheless clear that if steps were taken to oversample French-speaking immigrants, such a longitudinal study would provide a wealth of information on the settlement process for these immigrants in Francophone minority communities.[127]

This kind of oversampling has already shed considerable light on the activities of allophones in Quebec.

We succeeded in obtaining a considerable sample in Quebec, not only for Quebec Anglophones by mother tongue, but also for allophone immigrants who favour English. Since competition between English and French is an important issue in Quebec, we significantly oversampled the allophones who favour French to understand the dynamics. We asked all the same question about access to health care and the various means of fostering community vitality.[128]

A similar approach would no doubt help address this major gap in the data serving as a basis for informed decisions on receiving more immigrants in Francophone minority communities.

When the Strategic Plan was launched, the Plan’s initial targets were maintained: that 4.4% of all immigrants in 2008 be Francophones settling in Francophone communities outside Quebec. Knowing that Canada intends to accept between 240,000 and 265,000 immigrants in 2007, and assuming that this number remains constant for two years, that would mean between 10,560 and 11,660 Francophone immigrants per year settling in Francophone communities outside Quebec. Yet the Strategic Plan also states that “according to forecasts, approximately 15,000 French-speaking immigrants will settle outside Quebec in the next five years” (p. 3), nearly four times less than the objectives set, which creates substantial confusion. The Plan also indicates that it will take about fifteen years to achieve the annual target of 8,000 to 10,000 Francophone immigrants settling in Francophone minority communities.[129] In other words, it will take until 2021 to meet objectives that are lower than those the Plan maintains for 2008.[130] In launching the Strategic Plan, Minister Solberg also announced the renewal of the Steering Committee’s mandate for five years, from 2006 to 2011, to oversee to the Plan’s implementation.

Appearing before the Committee, the Deputy Minister responsible for the Strategic Plan indicated that this confusion was simply due to a misunderstanding of the term “French-speaking immigrant” which from now on should be understood as an “immigrant whose mother tongue is French, or whose first official language is French if the mother tongue is a language other than French or English” (p. 4). This apparent clarification actually confuses matters further since this definition is identical to the definition of “first official language spoken” as used by Statistics Canada, and it is precisely this definition that was used to set the target of 4.4% of immigrants. In other words, this apparent change in definition should never have resulted in a change in targets since the targets were in fact based on this definition.

Disregarding these inconsistencies and simply accepting that the new targets are about 15,000 over the next five years (p. 3), or an average of 3,000 per year, this would amount to 1.25% of Canada’s total immigration, which is very far from the original stated objective of 4.4%. Yet the Plan itself states that: “According to Statistics Canada, the number of immigrants who settle outside Quebec and whose mother tongue is French has varied between 1 percent and 1.5 percent for several years.”(p. 4). In other words, the new targets to be achieved under the Plan represent no change from the situation that has persisted for years.

These ambiguities are not conducive to the success of the Strategic Plan or to mobilizing the interested stakeholders to achieve a clear target, even though its objectives are noble and are strongly supported by the communities. It would be unfortunate to jeopardize the success of initiatives designed to foster immigration to Francophone minority communities simply because of confusion in the preparatory work.

Finally, if the real starting point cannot be clarified and the targets are vague, it becomes virtually impossible to determine whether the Plan’s objectives have been achieved. The Plan does not include any follow-up mechanism or timeframe for tracking progress towards the results, such as every year or at the halfway mark. In other words, if the Plan’s objectives were attained or even greatly surpassed, it would be impossible to know this. The Committee therefore recommends:

Recommendation 6

That Citizenship and Immigration Canada, together with the provinces and territories:

§ Ask Statistics Canada to oversample Francophone immigrants in the Longitudinal Survey of Immigrants to Canada;

§ Ask Statistics Canada to conduct a rigorous demographic study of Francophone immigrants in minority communities and the factors in their mobility;

§ Identify best practices for their harmonious integration into Francophone minority communities;

§ Completely re-evaluate the targets and definitions in the Strategic Plan to Foster Immigration to Francophone Minority Communities, specifically the anticipated increase in the number of immigrants settling in Francophone minority communities following the implementation of the Strategic Plan;

§ Establish a time frame and develop a rigorous follow-up mechanism in order to regularly verify the results obtained.

3.3. Budget measures 2006-2007

Appearing before the Committee, Minister Solberg confirmed that $307 million would be allocated to new settlement measures for immigrants. An initial $111 million will be provided in 2006-2007, and a further $196 million in 2007-2008. Three-quarters of this total amount, or $230 million of the $307 million, is earmarked for Ontario, and $77 million for the other provinces excluding Quebec.

This funding is in addition to the $90 million over two years already included in the 2005-2006 Budget. This brings the government’s total commitments for immigrant settlement for the next two years to $146 million in 2006-2007 and $251 million in 2007-2008. Without knowing what the 2008-2009 and subsequent budgets will provide, the total budget for immigration as a whole will likely exceed $1 billion over the next four years (see table on Page 91).

The 2006-2007 Budget does not include any specific funding for Francophone minority communities but, according to Daniel Jean, Co-Chair, Government Side, Citizenship and Immigration Canada Steering Committee — Francophone Minority Communities: “Clearly, some of that funding will promote immigration and help meet the specific integration needs of Francophone immigrants.”[131] These increases will of course be more noticeable in Ontario.

Of course, in a province like Ontario, where we have a very substantial Francophone community, Francophone settlement agencies and groups will see a big increase in the funding they get. Actually, in Ontario, CIC has a very direct say in how funding is allocated, but we take input from settlement agencies and obviously from the Province of Ontario. Yes, there will be substantial increases in funding for all settlement agencies.[132]

The funding provided in the budget will be distributed to the provinces, which will manage it through their settlement agencies. Some of these agencies are already at work in Francophone minority communities and they will likely receive their share of this funding although specific shares were not stipulated.

This $307 million investment is independent of the Strategic Plan to Foster Immigration to Francophone Minority Communities launched in September 2006 by Ministers Solberg and Verner. This Strategic Plan did not contain any financial commitment. Daniel Jean did however mention some potential avenues to fund the Strategic Plan’s objectives:

Part of the funding […] will come from existing programs. First, the Action Plan for Official Languages, launched in March 2003, allocated $9 million over five years to promote immigration within Francophone communities. Second, the additional settlement funds announced for CIC in the 2006 budget will support some of the initiatives of the strategic plan. These new funds will be used to meet the immediate needs of immigrants by improving existing programs and developing pilot projects for target client groups, including Francophone minority communities. Third, we will rely on the leverage effect that can be created by forming strong partnerships with other departments, be it the Department of Heritage, the Department of Health or others. Fourth, the implementation committee will examine the existing funding mechanism for the implementation of the strategic plan and will identify shortfalls to ensure its success.[133]

BUDGET MEASURES RELATING TO IMMIGRATION |

||||||||

2005-2006 |

2006-2007 |

2007-2008 |

2008-2009 |

2009-2010 |

TOTAL |

|||

Budget 2005 |

||||||||

Integration and settlement |

20 |

35 |

55 |

80 |

108 |

298 |

||

Client services |

20 |

20 |

20 |

20 |

20 |

100 |

||

Total measures already announced |

40 |

55 |

75 |

100 |

128 |

398 |

||

Budget 2006 |

||||||||

Settlement |

111 |

196 |

307 |

|||||

Permanent residency permit |

134 |

90 |

224 |

|||||

Recognition of qualifications |

6 |

12 |

18 |

|||||

Total new measures |

251 |

298 |

549 |

|||||

Total of both budgets |

40 |

306 |

373 |

100 |

128 |

947 |

||

The communities’ first challenge will be to ensure that they receive their fair share of these significant investments. According to Marc Arnal, Co-Chair, Community Side, Citizenship and Immigration Canada Steering Committee — Francophone Minority Communities, $50 million over five years would be needed to achieve the objectives of the Strategic Plan unveiled in September 2006. [134]

There are significant differences among the provinces as to the intensity of immigration initiatives that have been developed. In Newfoundland and Labrador, a structured program to attract Francophone immigrants, including candidates from Romania, is in the early stages. In Alberta, no specific recruitment measures have been implemented yet, due in part to the need to manage interprovincial migration first of all. “For now, people are arriving in Alberta of their own initiative.”[135]

The most significant achievements have been in Manitoba. Various witnesses indicated this. “What started the whole movement in Manitoba was a mission to Morocco, where presentations were made. The Société franco-manitobaine wound up with some 20 people on its doorstep one fine day, and was not at all ready for them. That is what led to the establishment of structures.”[136]

Two key elements were cited above all others to explain this success:

§ The geographic density of Francophone populations makes it easier live in French than in communities that are more spread out; and

§ The province played an active role in developing and funding settlement structures.

In Manitoba, cooperation between the provincial and federal governments appears to have been decisive: “It is because they set up reception structures, targeted the type of immigrants who would want to stay in Manitoba and lastly, designed recruiting tools with us, and developed some of their own. That is what we have to do. The job has to be done in several stages.”[137] The province’s efforts stem from a strong stance in favour of immigration overall, including a “nominee program” that allows the province to target immigrants based on its specific needs.

The most successful province so far in employing the provincial nominee program is Manitoba. Manitoba last year brought in 4,600 people under their provincial nominee program, versus my province of Alberta at 611, and I think B.C. had 800. So Manitoba is very aggressive, and they do a number of things with it. They use it to target a couple of specific groups that are already established in Manitoba, in particular the Filipino community. They have a population in Winnipeg, in particular, so they reach out to the Philippines and say, “Come here. We’ll find you a job. We have a welcoming community you can step right into.[138]

To secure the support of Francophone communities, the Manitoba government has agreed to make a special effort to help Francophone communities recruit candidates: “The provincial government has set a Francophone immigration target of 7% for a population of 4%, recognizing that it had to make up for past mistakes.”[139]

What should be noted here is that the idea of making it a priority to support immigration came from both the province and the community networks involved in the Agrandir l’espace francophone project launched in 2001. The similarities between this initiative and the federal government’s objectives, especially under the Action Plan for Official Languages, in turn mutually reinforced each other in this specific case, but much less so in other provinces. This is another example of the multiplier effect of an alliance among community networks, the provinces and territories and the federal government, as is also demonstrated in the results achieved by Société Santé en francais. Moreover, evident from the comments about these initiatives that a sense of cooperation is developing beyond the initial files in question.

Last year, Manitoba took in slightly more than 300 Francophone immigrants. That’s a lot, if you compare that figure to the number we took in four or five years ago, and we intend to go even further […] We’ve set ourselves the following objective: an average of 700 immigrants a year for the next 20 years. At first, it will be a bit slow, but I believe we’ll be exceeding that number in a few years. We’re also working with the province of Manitoba, which is a world leader in immigration. This year, the province aims to take in 10,000 immigrants. That figure has nearly been achieved, and, in the last Throne Speech, a new objective was set, that of taking in 20,000 persons by 2011. We want to maintain the same percentage of Francophones and ensure that there are Francophones immigrating to Manitoba. We are a welcoming land and we’re proud of what we’re doing.[140]

This necessary cooperation does not of course mean that everything is smooth sailing and relations between the Francophone communities and the provincial government are now harmonious, as the President of Société franco-manitobaine clearly noted.

We’re facilitating Francophone immigration. I can’t say we’re being consulted, but, in the cases we’ve handled, the province has helped us bring in immigrants to Canada as quickly as possible. The government has reduced waiting times. In Manitoba, the waiting period is three to six months, which is absolutely impossible in other provinces: it’s not feasible […] Our partnership with the province is mainly in this area, and we’re working in very close cooperation with its representatives in that regard.[141]

There are also a lot of housing problems in the part of Saint–Boniface where a large number of immigrants wish to settle, and the services of the reception centre are insufficient. The Minister of Citizenship and Immigration confirmed that the new investments could help address this very situation: “We’ve already started to do some things in St. Boniface. Because of the strategy, initiatives are already under way to help people find suitable housing, as this is a real challenge. We are very aware of this, but the strategy, combined with the $307 million, means we now have the means to implement the strategy in a meaningful way.”[142]

The fact remains however that Manitoba is a very positive example on the whole and could serve as a model for initiatives in other provinces:

Manitoba has become a land of attraction. Francophones who come from elsewhere also want to settle in this kind of region to ensure a future for their children. That was my selling argument when I went overseas to sell my institution, the Collège universitaire de Saint–Boniface. I told people to come to Manitoba because they could continue studying in French and, at the same time, live in an Anglophone setting, which would make them perfectly bilingual. In many cases, people want to settle in Manitoba because they want their children to become bilingual.

Immigrants have understood that linguistic duality is an extraordinary asset. Moreover, immigrants have changed the linguistic dynamic of our institutions. It’s thanks to immigrants that we increasingly hear French spoken in the corridors of the university college. There are also people who come from the immersion system. That creates a new dynamic and a new type of wealth. The initiatives taken by the communities should be supported.

First there has to be a change in attitude before we get there, and I think we’re on the right track. There is good reason for me being here today: I may be the tree that hides the forest. There are lots of talented people asking only to serve Canada, to settle here, to raise their families here and to find niches in order to provide the required assets in this environment.[143]

3.5. Role of the federal government

While the provincial government works with the communities on certain projects, the federal government can serve as a facilitator. This cooperation between the provinces and official language minority communities is however far from natural. In some cases, for community organizations, involving the province in immigration agreements can also cause some irritants, such as the requirement to show the need for services in French, when, of course, there is no demand for them since there are none. The federal government’s role is then to follow through on its own commitments under Part VII of the Official Languages Act and to be persuasive with the provinces and territories in negotiating transfer agreements.

If the province does not clearly see the importance of allocating some of the funding it receives to French-language immigrant settlement agencies, the needs are so great in the majority community that there is little incentive to do so. At present, the agreements on immigration signed with the provinces include clauses requiring the provinces to consider official language minority communities, and to report any initiatives taken in this regard. These clauses can however be interpreted differently by the provincial governments, and do not include specific financial requirements such as for instance allocating a proportionally equal or greater amount to the province’s Francophone communities. As a result of this need to justify investments in settlement structures for Francophones, some parties saw the signature of these agreements as a step backward as compared to the bilateral agreements between the federal government and the communities that were previously used to fund immigration projects.[144]

Similarly, the communities of Northern Ontario would like to have the means to receive more immigrants, especially in areas such as Sudbury where there is nearly full employment, but the fact that immigrants are naturally drawn to larger centres prevents the communities from receiving funding. With that funding, these communities could attract many Francophone immigrants to places other than Toronto.

We have to convince immigrants who settle in Ontario to go up north, where job opportunities are available […] The mining industry is doing well. We need appropriate settlement structures […] At the present time, we have no support to investigate or analyze the file of an immigrant from another country that we know little or nothing about. How can we more effectively facilitate new Canadians’ transition to Canada, to our educational system, to complete their education, if need be, and particularly outside Toronto? It would be nice to have direct incentives for new Canadians to encourage them to settle in Sudbury, Timmins, Hearst, and so on.[145]

The federal government included linguistic clauses in most of the agreements relating to immigration that it signed with the provinces, but the clauses do not appear to impose specific obligations on the provinces if they do not consider them justified.

In the agreements signed with the provinces, we included a provision asking them to make efforts in this respect. On a practical level, we want to show the other provinces the results achieved by such initiatives as those in Manitoba, in order to encourage them. We also hold meetings with the communities in the municipalities and provinces so that they encourage their provincial authorities to do the same.[146]

So it seems to be more of an incentive than a real condition that the government imposes on the provinces in order to obtain funding. To clarify the federal government’s role, which is to remind the provinces if necessary of their obligations to official language minority communities, and in view of the remedial role the Government of Canada must play for these communities, the Committee recommends:

Recommendation 7

That, pursuant to his obligations under Part VII of the Official Languages Act, the Minister of Citizenship and Immigration, in making transfer payments to the provinces and territories under the Immigrant Settlement and Integration program, invite the provinces and territories other than Quebec to allocate to the Francophone community a proportion of these transfers that is at least one percentage point above the proportion of the province’s residents whose first official spoken language is French.

Moreover, there are provinces without recognized settlement agencies serving the specific needs of Francophone immigrants. The coordinator of the immigration file for the Fédération des francophones de Colombie–Britannique noted in this regard that:

Francophone immigrants are “taken in through Anglophone organizations. So they aren’t as aware as we are of all the French-language services that immigrants can access, such as schools, continuing training centres, Francophone associations, community centres, and so on. We’d like to adopt some things from the Quebec model. It’s already being promoted outside Canada for Francophone immigration outside Quebec, in particular in British Columbia, but we’d also like to keep the model, which enables us to recruit immigrants, in addition to integrating them ourselves, that is to say having our own intake and orientation services in British Columbia, and to do that through Francophone, not Anglophone organizations.”[147]

The Committee therefore recommends:

Recommendation 8

That Citizenship and Immigration Canada invite the provinces and territories other than Quebec to designate at least one community organization per province and territory to coordinate the integration and settlement of Francophone immigrants and that this agency be able to conduct independent recruitment initiatives.

There were various references to the difficulty that Francophone communities have in attracting Francophone immigrants since the Quebec government monopolizes the promotion of Canada’s Francophone communities abroad. These efforts are quite understandable of course, but it seems inconsistent that the Government of Canada should develop a Strategic Plan to encourage Francophone immigration to provinces other than Quebec on one hand, and on the other does not make every effort to fully promote Canada’s linguistic duality abroad, including through its embassies. The Committee therefore recommends:

Recommendation 9

That Citizenship and Immigration Canada intensify its efforts to recruit Francophone immigrants through its foreign embassies, and support Francophone minority communities’ recruitment efforts by adequately training and raising the level of awareness of embassy staff, and by guaranteeing the availability of printed information in both official languages.

The effectiveness of the Government of Quebec’s efforts abroad is especially noteworthy as regards the recruitment of foreign students. The bilateral agreements that Quebec signs with countries belonging to the Francophonie offer tuition fees that other French-language institutions in Canada cannot compete with. It costs on average $2000 per year for a foreign student from Tunisia to study in Quebec, but would cost that same student $17,000 per year to study in Alberta. Witnesses involved in French-language postsecondary education outside Quebec stated that this compromises one of the most effective ways of recruiting immigrants. The Committee therefore recommends:

Recommendation 10

That the Government of Canada negotiate an agreement with Quebec, the other provinces and territories, and postsecondary institutions, to find a formula that is satisfactory to all parties to encourage the recruitment of international Francophone students throughout the country in an equitable manner.

[107] Marc Arnal, Co-Chair, Community Side, Citizenship and Immigration Canada Steering Committee — Francophone Minority Communities, Evidence, October 3, 2006, 9:40 am.

[108] See in this regard Robert Donnely (President, Voice of English-Speaking Québec), Evidence, November 8, 2006, 10:50 am.

[109] David Laliberté, President, Centre francophone de Toronto, Evidence, November 9, 2006, 9:15 am.

[110] Marie Bourgeois, Director General, Société Maison de la francophonie de Vancouver, Evidence, December 4, 2006, 8:35 am.

[111] For an overview of some specific measures, see Daniel Jean (Co-Chair, Government Side, Citizenship and Immigration Canada Steering Committee — Francophone Minority Communities), Evidence, October 3, 2006, 10:05 am.

[112] Some people consider the addition of the “immigration” sub-component to be the greatest success of the Action Plan, especially in view of the mobilization that resulted from the creation of the Citizenship and Immigration Canada Steering Committee. See Luketa M’Pindou, Coordinator, Alliance Jeunesse-Famille de l’Alberta Society, Evidence, December 5, 2006, 10:55 am.

[113] Jack Jedwab, Immigration and the Vitality of Canada’s Official Language Communities: Policy, Demography and Identity, February 2002, available online at: http://www.ocol-clo.gc.ca/archives/sst_es/2002/immigr/immigr_2002_f.htm; and Carsten Quell, Immigration and Official Languages: Obstacles and Opportunities for Immigrants and Communities, November 2002, available online at: http://www.ocol-clo.gc.ca/archives/sst_es/2002/obstacle/obstacle_f.htm.

[114] FCFA, Évaluation de la capacité des communautés francophones en situation minoritaire à accueillir de nouveaux arrivants, available online at: http://www.fcfa.ca/media_uploads/pdf/51.pdf.

[115] Jean–Pierre Corbeil, Senior Population Analyst, Demography Division, Statistics Canada,, Evidence, October 17, 2006, 9:10 am.

[116] Ibid.. The significant discrepancy in the data from the two sources is likely due to the fact that the FCFA did not make a distinction between the “first official language spoken” and the residual category, “first official language spoken English-French.” They were merged instead, which inflated the real number of Francophone immigrants.

[117] Action Plan for Official Languages, p. 48.

[118] See Marc Arnal (Dean, St. Jean Campus, University of Alberta), Evidence, December 5, 2006, 8:30 am.

[119] This proportion was established further to the changes made in 2003 to the Immigration and Refugee Status Act, which stipulated in the Preamble that “Canada’s immigration programs have to respect and reflect the country’s current demographics.”

[120] Jack Jedwab, Immigration and the Vitality of Canada’s Official Language Communities: Policy, Demography, Identity, February 2002, available online at: http://www.ocol-clo.gc.ca/archives/sst_es/2002/immigr/immigr_2002_e.htm; and Carsten Quell, Immigration and Official Languages: Obstacles and Opportunities for Immigrants and Communities, November 2002, available online at: http://www.ocol-clo.gc.ca/archives/sst_es/2002/obstacle/obstacle_f.htm.

[121] Strategic Framework to Foster Immigration to Francophone Minority Communities, Appendix A.

[123] Available online at: http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/francophone/report/initiatives.html.

[124] Strategic Plan, p. 11.

[125] Strategic Plan to Foster Immigration to Francophone Minority Communities, p. 4.

[126] Fédération des communautés francophones et acadiennes du Canada, Évaluation de la capacité des communautés francophones en situation minoritaire à accueillir de nouveaux arrivants, available online at: http://www.fcfa.ca/media_uploads/pdf/51.pdf.

[127] Jean–Pierre Corbeil (Senior Population Analyst, Demography Division, Statistics Canada), Evidence, October 17, 2006, 9:10 am.

[128] Ibid., 9:30 am.

[129] Ibid.

[130] The Plan identifies other specific targets: 6,000 Francophone economic immigrants per year (p. 9), 2,000 international students per year at French-language postsecondary institutions outside Quebec (p. 10), and 1,600 refugees in official language minority communities (p. 10). The rationale for these targets is not explained.

[131] Daniel Jean, Co-Chair, Government Side, Citizenship and Immigration Canada Steering Committee — Francophone Minority Communities, Evidence, October 3, 2006, 9:45 am.

[132] The Hon. Monte Solberg, Minister of Citizenship and Immigration, Evidence, October 24, 2006, 10:35 am.

[133] Daniel Jean, Co-Chair, Government Side, Citizenship and Immigration Canada Steering Committee — Francophone Minority Communities, Evidence, October 3, 2006, 9:10 am.

[134] Marc Arnal, Dean, St. Jean Campus, University of Alberta, Evidence, December 5, 2006, 8:30 am.

[135] Luketa M’Pindou, Coordinator, Alliance Jeunesse-Famille de l’Alberta Society, Evidence, December 5, 2006, 11:05 am.

[136] Marc Arnal, Co-Chair, Community Side, Citizenship and Immigration Canada Steering Committee — Francophone Minority Communities, Evidence, October 3, 2006, 9:50 am.

[137] Daniel Jean, Co-Chair, Government Side, Citizenship and Immigration Canada Steering Committee — Francophone Minority Communities, Evidence, October 3, 2006, 9:40 am.

[138] The Hon. Monte Solberg, Minister of Citizenship and Immigration, Evidence, October 24, 2006, 10:35 am.

[139] Marc Arnal, Dean, St. Jean Campus, University of Alberta, Evidence, December 5, 2006, 8:30 am.

[140] Daniel Boucher, President and Director General, Société franco-manitobaine, Evidence, December 6, 2006, 8:30 pm.

[141] Daniel Boucher, President and Director General, Société franco-manitobaine, Evidence, December 6, 2006, 8:40 pm.

[142] The Hon. Monte Solberg, Minister of Citizenship and Immigration, Evidence, October 24, 2006, 10:10 am.

[143] Ibrahima Diallo, Chair of the Board, Société franco-manitobaine, Evidence, December 6, 2006, 8:50 pm.

[144] Jamal Nawri, Coordinator, Immigration, Fédération des francophones de la Colombie-Britannique, Evidence, December 4, 2006, 9:45 am.

[145] Denis Hubert, President, Collège Boréal, Evidence, November 10, 2006, 10:25 am.

[146] Daniel Jean, Co-Chair, Government Side, Citizenship and Immigration Canada Steering Committee — Francophone Minority Communities, Evidence, October 3, 2006, 10:15 am.

[147] Jamal Nawri, Coordinator, Immigration, Fédération des francophones de la Colombie-Britannique, Evidence, December 4, 2006, 8:55 am.