LANG Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

2. Health

The second largest investment under the Action Plan went to health, at $119 million, which is much less than the $381.5 million allocated to education. In the spring of 2006, recognizing the importance of the health sector as an indicator of community vitality, the Committee undertook a study on access to health care in official language minority communities, as well as a study on immigration. Both were then incorporated into the study on vitality, which took the Committee on a cross-country tour. This explains why this section on health includes testimony from community representatives as well as experts and officials with the Official Languages Office at Health Canada.

This section is divided into two subsections:

§ The first provides an overview of official language minority communities as regards health care: what we know about the state of members’ health and what the testimony and expert analyses reveal about access to health services;

§ The second part outlines the features of the health component of the Action Plan, assesses the results based on the evidence gathered, and makes recommendations on the three key areas for action cited in the plan: networking, training and retention, as well as development of primary care.

Our analysis shows that the health component of the action plan has by far produced the most concrete results. This success is the result of the tremendous work done by the Société Santé en français, the Consortium national de formation en santé, and the Community Health and Social Services Network. Bearing in mind the reservations noted in section 2.2.2.3, the work of these three organizations must be duly recognized and the government should not have the slightest hesitation in offering long-term budget assistance for the initiatives they have put forward.

2.1. OVERVIEW OF HEALTH STATUS AND ACCESS TO HEALTH CARE

2.1.1. Health Status of Francophone Minority Communities

It is extremely difficult at this time to know the exact state of health of members of official language minority communities. The 2001 report of the Comité consultatif des communautés francophones en situation minoritaire (CCCFSM) indicates that minority Francophones have poorer health in general than other residents of the same province.[30] This finding is supported by a 2001 study coordinated by the Fédération des communautés francophones et acadienne du Canada (FCFA).[31] The FCFA referred back to previous provincial studies conducted in 1999 in Ontario and in the 1980s in New Brunswick. This finding is thus supported by overlapping data from various studies.

Without reliable data, the FCFA study had to use indirect data on the “determining factors” of health rather than actual data on individuals’ health. The findings on the health of members of Francophone minority communities included in the 2001 CCCFSM report are thus based on extremely fragmentary data that do not show any changes in this regard to this date, nor do they indicate whether there will be any improvement or deterioration of the situation in the future.

This shortcoming was also identified in the FCFA study. With respect to the health of members of Francophone and Acadian minority communities, this study noted that “unfortunately there is no reliable and shared information for all Francophone and Acadian minority communities.”[32]

Some of the evidence heard pointed to avenues for future research that are consistent with the FCFA study, but there are still very few conclusive findings. Appearing before the Committee, Professor Louise Bouchard from the University of Ottawa indicated that, according to her studies, “living in a minority situation, whether it be Anglophone or Francophone, seems to have a negative effect on an individual's perceived health status. It goes beyond one's financial situation, level of education or sex; there is something else at play. Also, this effect appears to be stronger among men than women, according to our analysis model.”[33] This is certainly an interesting avenue, but the information is insufficient to convincingly demonstrate the link between language and health status. As suggested by some other research mentioned by Jean-Pierre Corbeil of Statistics Canada, the Anglophones of Quebec are by comparison in a special situation that cannot too readily be compared to that of Francophone minorities.

As everybody knows, the situation of Anglophones in Quebec is very different from what we find outside Quebec, for a number of reasons. Clearly Francophones outside Quebec are far older and more likely to need health care. Far more Francophone seniors are unilingual. For these people, the stress or concerns associated with the need to be understood and receive services in one's own language may be far greater than for Anglophones in Quebec, who have wider access to English health care services.[34]

Researchers do however seem to agree that “the minority/majority ratio appears to reflect social inequality and unequal access to resources which, together with the other social determinants of health — socioeconomic status, education, literacy, age, sex and immigration — contributes to disparities in health.” [35] This also appears to explain the difference between the average income of Anglophones and Francophones in New Brunswick. Eliminating the influence of factors other than language, there is still a significant difference between Anglophones and Francophones. [36]

So there are plenty of avenues of research, but there are obviously also significant gaps in our knowledge of the health status of members of official language minority communities. In the initial recommendations made in 2001 by the Comité consultatif des communautés francophones en situation minoritaire (CCCFSM), there were two components that were not chosen and that together might have filled some of these gaps: information technology and research.

Hubert Gauthier, then co-chair of the CCCFSM, expressed his concerns to the Committee about measuring the health status of Francophones. The difficulties are apparently in large part due to the fact that data collection systems, including those related to the Health InfoWay, do not identify Francophones. Using information technology to more effectively track Francophones’ health status and adding “research” as a sub-component of the health component in the next action plan would give a better indication of the health of minority community members: “We know that it is not as good, but we want to know exactly on what points, and we also want to know what to do about it. Research is helping us to do this.”[37]

Professor Bouchard suggested that the reason for this gap is that administrative health data cannot be used to study official language minority communities because the language variable is not included in the health files managed by institutions, files that are used to compile provincial statistics. Nor is there systematic oversampling of official language minority communities in national health studies coordinated by Statistics Canada.[38]

The Committee therefore recommends:

Recommendation 1

That the Government of Canada suggest that the provinces include the language variable in health records, while respecting their jurisdiction, and that Statistics Canada use oversampling of official language minority communities in its next National Population Health Survey.

2.1.2. Access to Health Care Services for Minority Francophones

Access to health care services is certainly a key factor for a community’s long-term vitality. It appears that the availability of such services in the patient’s language also has a direct influence on the overall health of members of that community.

Studies clearly show that there is a connection between the ability to obtain services in our mother tongue and the quality of care we receive. If we are unable to properly understand the professional, communication is diminished and, consequently, there will be health care problems, the doctor's instructions will be misunderstood or the prescription we are given will be misunderstood.[39]

Professor Bouchard confirms this and adds:

Despite universal access, users of the health care system who cannot communicate in their language do not have the same access or the same quality of care as their fellow citizens. The language barrier limits the use of preventive services, limits access to all services that require communication, particularly mental health, rehabilitation and social services, as well as adequate follow-up of patients, which in turn contributes to the increase in emergency services and the use of supplementary medical examinations to compensate for difficulties in communication.[40]

With respect to access to services, the data is much more solid than that regarding health status, yet it is based on subjective assessments and should be used carefully. According to the same CCCFSM report of 2001 cited above, between 50% and 55% of Francophones in minority communities often have little or no access to health services in their first language.[41] These findings are based on the same study coordinated by the FCFA.[42] The report also notes that “the results […] must be interpreted carefully. This exercise is not a scientific study with a controlled margin of error.”[43]

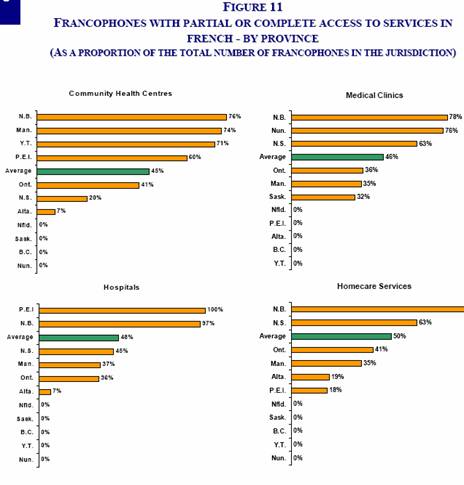

More specifically, the FCFA study noted that “between 50% and 55% of Francophones had no (less that 10% of the time) or very little (between 10% and 30% of the time) access to health services in French.”[44] It also noted that access varied greatly by province and by type of service offered.

Source: Fédération des communautés francophones et acadiennes du Canada, Pour un meilleur accès à des services de santé en français, 2001, p. 26.

This table shows for instance that close to 25% of Francophones in New Brunswick and Manitoba denied having access to services in French at their community health facility, while this figure is 59% in Ontario, 80% in Nova Scotia and 93% in Alberta. Some services are simply not offered in some provinces. Access to health care services was 3 to 7 times better for Anglophones than Francophones within any given province or territory.”[45]

These figures are important because they were used as the basis for the recommendations the CCCFSM made in 2001 to the Minister of Health. These recommendations in turn form the basis for the health component of the Action Plan for Official Languages, and it was this Committee that provided the impetus for creating the Société Santé en français.

Appearing before the Committee, Jean-Pierre Corbeil presented other research that further clarified some of the statements in the FCFA study:

A study published by Louise Marmen and Sylvain Delisle from Statistics Canada in 2003 on health care services in French outside Quebec revealed the difficulties encountered by Francophones outside Quebec with respect to obtaining services in French, resulting from the fact that in many provinces, Francophones are proportionately higher in numbers in rural areas, whereas Francophone specialists or other professionals likely to provide services in French work mostly in large urban centres.[46]

In their opinion, the language variable is thus not as decisive as the fact that Francophones are more concentrated in rural areas and thus have less ready access to services in general, which are scarcer in the regions.

The evidence heard illustrated how much the situation can vary from province to province. In Newfoundland and Labrador, for instance, the Francophone community’s lack of demographic weight means that health services in French are practically non-existent, although interpreters can be provided if patients wish. “If there is a translation service, there is a danger of misunderstanding. It is also no easy matter to consult a doctor and to explain the problem through another person. That is not what we feel like doing when we are lying on a stretcher.”[47]

In Nova Scotia, French-language health care services have not been systematically developed. That is why it has become important to identify the location of professionals who can serve the French-speaking population:

There's no French-language health centre in Halifax. Currently, access to health services in French in Halifax is entirely a matter of chance. That's why the professional directory has become very important for us. We're starting to locate professionals. We found a certain number of Francophones at one centre, but it's an Anglophone centre that operates in French. In Chéticamp, which is a very homogeneous region, there is a system that could unofficially be called a Francophone centre.[48]

The situation is certainly better in New Brunswick than elsewhere, but the progress made is fragile and the best approach for the majority does not necessarily work for the minority.

In New Brunswick, the Act is clear. It provides for health services for all citizens, in the language of their choice, wherever they may be in the province, and that's what we want. The reality, on the other hand, is something else again. Unfortunately, when the time comes for policy decisions, they are made the same way for everyone. History has taught us that in a minority context, the minority often takes more of a hit than the majority. It is therefore a question of providing tools, empowerment and capacity building.[49]

There are also problems with universal access to health services in French throughout New Brunswick as regards specialized care. In Moncton, many specialized services are only available at the Moncton Hospital, where services are provided primarily in English. It is difficult for Francophones to obtain these services in their own language. Conversely, services are offered primarily in French at Georges Dumont Hospital, but can also be provided in English according to patients’ needs.

Concerning more specialized services, we see that Francophone institutions are also able to provide services in English. The reverse is not necessarily true. We therefore have work to do in order to bring about broader policies so that Francophones can access specialized services, which they could not obtain, for example, at Georges Dumont Hospital in Moncton.[50]

In Eastern Ontario, where there is a significant concentration of Francophones, accounting for up to 70% of the population in Prescott and Russell counties, the decision regarding the Montfort Hospital gave a significant boost to the integration of French-language services. “The Eastern Ontario health system includes 20 hospitals, 66 community support services organizations, 26 mental health community organizations, 8 community health centres […] Of this number, 66 agencies are said to be designated or identified, meaning that they are compelled by the province to offer health services in French.”[51] Five of these agencies are postsecondary teaching institutions that offer services in French.

In Saskatchewan, on the other hand, there are no Francophone neighbourhoods that would justify the establishment of a community health centre offering various services. The Committee heard some troubling testimony in this regard.

For instance, during a trip to the region, a lady came to see me. She showed me how she would use the card prepared by the nurse who is in charge of her because she speaks only French. She was eight months pregnant, did not speak a word of English and lived in a rural environment. This lady had to carry the card around with her, in case she might have to call 911, and had to know what to say over the telephone because emergency services are not bilingual. This gives you some idea of the scope of the problem. In some places and in certain regions, this problem is still widespread.[52]

In southern Ontario, there are few Francophones and they are widely dispersed, making it difficult to coordinate services between communities and regional health authorities. “The Réseau franco-santé du sud de l'Ontario covers an enormous territory. This complicates matters when one wants to develop priorities at a local level because decisions will soon be made, in Ontario, by the LHINs, the Local Health Integration Networks, which are the regional decision tables.”[53]

In Northern Ontario, the situation varies greatly from region to region:

For example, in the western part of the region, the City of Sault Ste. Marie has declared itself to be unilingual Anglophone. So, there is very little available there. In fact, health care services in French are practically non-existent there. And because Francophones constitute an aging population in that region, the negative impacts on them are significant.

In the central region, Sudbury does provide health care services in French. Unfortunately, health care services in French are not always offered consistently there.[54]

In Manitoba, despite the Francophone community’s deep historical roots, services in French have only been provided since quite recently:

I won't go back to 1871 and tell you that the Hôpital Saint-Boniface was the first hospital established west of Ontario. It was not until 1989-1990 that it officially received a mandate to provide French-language services to the population of Saint-Boniface and Saint-Vital.

In 1999, when the Regional Health Authority was created, the hospital was officially given a mandate to actively offer French-language services to the Francophones of Winnipeg, particularly those of Saint-Boniface and Saint-Vital.[55]

Community networks have since taken various initiatives that we will discuss later on.

Without significant demographic concentrations in Alberta, it makes it very complex to coordinate a range of services in French.

The health department has delegated many responsibilities to the regional health authorities. The province is broken up into many smaller jurisdictions, and our Francophone communities are scattered among all these regional health authorities. So we have to meet with each regional health authority in the province, since they are the entities we need to work with.

Our team consists of one person, and there are many people to meet with. Obviously, repeating the same message nine times to people who do not know us well is quite difficult.[56]

In British Columbia, the vitality of the community health network has apparently convinced the province of the soundness of its initiatives serving the French-speaking population.

From the outset, we managed to mobilize all the components of the health system to develop programs, starting with the BC Health Guide, or Guide-santé Colombie-Britannique, in French. The provincial health department acted as RésoSanté's main partner for that project since it's a departmental program.

To date, we've distributed more than 13,000 copies of the guide to the public, and more than 150 health cards have been translated. We've conducted some 20 awareness workshops in order to reach the Francophone community and health professionals who will be providing health services in French.”[57]

2.1.3. Health Status and Services for Anglophones in Quebec

For Anglophones in Quebec, despite the difficulty of being in a minority, their situation appears to be enviable:

Quebec has amended its health care act. Measures have been introduced for each regional health board to set up a committee tasked with ensuring that services are provided. Each board has to develop a plan to ensure that health care services are provided in English. [58]

Yet this reality belies the difficulties faced by Anglophones outside Montreal.

The situation of Anglophones in Quebec is different from that of Acadians or of Francophones living outside Quebec. Anglophones living in large urban centres such as Montreal manage quite easily to obtain services in their language. When they live in more remote areas, their experience is quite similar to that of Francophones.

A recent CROP poll showed that only 48 per cent of Anglophones in Quebec are able to access the services they need, primary services, in their mother tongue. So there are always major shortages in Quebec, whatever one might think.[59]

This statement is qualified however by Jean-Pierre Corbeil, from Statistics Canada. Anglophones in Quebec might well use the majority’s public institutional services less, but they benefit more than Francophones outside Quebec from community networks that offer health services in English.

We noticed, in past studies, that Quebec Anglophones make greater use of family networks and personal networks than do Francophones outside Quebec. The reality is significantly different for these two groups.

When it comes to fear or anxiety surrounding the ability to receive services in one's own language, we do not have a survey like the one that exists for Anglophones in Quebec, but we can assume that if the issue is intimately related to the availability of services in one's own language, it is less of a problem in Quebec than outside Quebec.[60]

Comparisons can therefore be made between Anglophones in Quebec outside Montreal and Francophones outside Quebec, but caution must be exercised with generalizations until more convincing data has been collected.

The wide range of problems encountered throughout the country demonstrates that a standard approach might not address the realities of official language minority communities. In that sense, and as it will be shown a number of times throughout this report, the best way to proceed is a province-by-province or territory-by-territory approach, allowing the federal government, the provincial government and/or the appropriate designated regional authorities, and of course community networks, to work as full partners.

The evidence gathered on access to services is certainly reliable, but it does not provide the scientific basis to document in detail the problems faced by the official language minority communities in each province. The Committee could have made a recommendation regarding support for research on access to services, but it would appear that many of the gaps in this regard will soon be addressed by the results of a major study by Statistics Canada, a post-census survey on the vitality of official language minority communities, whose initial findings will be released in October 2007. The result of a partnership between Statistics Canada and eight federal departments and agencies, this study is an impressive undertaking:

It is the first time that we have conducted a survey on this scale dealing exclusively with official language minorities. This was a survey of 50,000 people that includes 17 modules on topics such as education, early childhood, linguistic trajectory from childhood to adulthood, access to health care in the minority language, cultural activities, linguistic practices in the workplace, sense of belonging and subjective vitality, just to name a few. The sample size is expected to produce very reliable estimates of the difficulties regarding access to health services and the French-language services offered to Francophones. [61]

2.2. HEALTH COMPONENT OF ACTION PLAN FOR OFFICIAL LANGUAGES

Many of the health initiatives included in the Action Plan stem from the recommendations made in 2001 by the Comité consultatif des communautés francophones en situation minoritaire (CCCFSM). Hubert Gauthier, the current president of Société Santé en français, was the co-chair of the Consultative Committee at that time. The CCCFSM recommended that the Government of Canada adopt a comprehensive strategy with five components: networking, workforce training, intake centres, technology and strategic information, and finally research and awareness. The last two elements, deemed less of a priority, were dropped when the Action Plan was developed.

The Action Plan provided total investments of $751.3 million over five years, $119 million of which was allocated to health care through community development measures. The amount was broken down as follows:

§ $14 million for networking. An investment of $9.3 million for Francophone communities provided for the creation of 17 regional networks of health care professionals, institution managers, local elected officials, teachers and community representatives. This network, structured according to World Health Organization recommendations, is coordinated by the Société Santé en français, which represents the five groups of partners. The annual meeting of members is attended by five representatives of each of the 17 provincial or territorial networks of the Society, with one representative for each partner category. For Anglophone communities, the Community Health and Social Services Network is responsible for developing networks. With a federal investment of $4.7 million, it coordinated the establishment of a provincial network comprising 65 organizations, and nine local and regional networks that forge partnerships with regional planning bodies, health care service providers, researchers, subsidizing agencies, and communities.

§ $30 million for the Primary Health Care Transition Fund (2000 Agreement on Health). Primary care refers to the basic services or sometimes local services that should be universally available. It includes prevention, detection, examinations, information, treatment and long-term care. The Health Canada investment provided a substantial boost to a federal-provincial agreement concluded in 2000 and expiring at the end of 2006. For Francophone communities, the Midterm Report on the Action Plan for Official Languages mentioned 67 projects funded by Health Canada and coordinated by the Société Santé en français under the Primary Health Care Transition Fund. Of the $30 million allocated to this initiative, $20 million was earmarked for Francophones outside Quebec and $10 million for Quebec’s English-language network, to be managed by the Community Health and Social Services Network. For Anglophone communities, the Network approved 30 or so projects in 13 of the 16 regions of Quebec. One of the key aspects of this sub-component is the Préparer le terrain initiative, managed by each of the 17 networks coordinated by Société Santé en français. Its objective is to foster the development of plans that will include an assessment of the situation in the various communities in each province or territory, an inventory of the most pressing needs, and strategies for establishing French-language services that meet local needs. It is in a sense a work plan that will help direct future investments in the development of primary care.

§ $75 million for training, recruitment and retention. The lion’s share of the funding for the second priority of the health component, that is, $63 of $75 million over five years for training, recruitment and retention, is linked to the activities of the Consortium national de formation en santé (CNFS). Under the Action Plan, the CNFS undertook to train 1000 new health care professionals in Francophone minority communities by 2008. The goal is not simply to train health care professionals but if possible to ensure that they return to their community of origin after completing their education, and to promote access to training through distance education, partnerships or cooperation among institutions. For Anglophones, $12 million in funding will be used to strengthen human resources capacity, to serve Anglophones and to offer English-language services to isolated communities with the help of technology. These initiatives are coordinated by McGill University.

2.2.2. Results of the Health Component

2.2.2.1. Strong Federal-Provincial-Community Cooperation

In her Annual Report 2005-2006, the Commissioner of Official Languages notes that the most significant progress since the implementation of the Action Plan for Official Languages in 2003 has been with respect to community development.[62] Moreover, among all the sectors relating to community development, the greatest strides have been made in health care, in Dyane Adam’s opinion. She credits Société Santé en français for establishing French-language training programs for health professionals, and for developing regional network of professionals, institutions, government authorities and community organizations.

With regard to enhancing the vitality of official language communities, the structural achievement with the most lasting and the greatest multiplier effect is certainly the establishment of the networks themselves. In three years, these networks have become extremely important stakeholders for provincial governments in planning the services to be offered to official language minority communities:

Without that networking, nothing would have happened. The health care sector is a fairly technical, specific area. Had there not been networks there to act as a catalyst or foundation, a rallying point for the people actively involved in ensuring that health care services could be provided in French in Ontario, nothing would have happened. We would have services that lack oxygen, we would have health care professionals with nothing in their environment to remind them that they are Francophone, that they should be proud of being Francophone and proud to be able to provide services in French — in other words, this is value-added.[63]

While difficult to measure, one of the most important effects of establishing these networks and the resulting projects is the significant improvement in relations between official language minority communities and provincial governments. This can be seen for instance in the recent decision by the Government of Manitoba to designate the Conseil Communautés en Santé as the official representative for Francophones on matters of health and social services in Manitoba.[64]

The results in Ontario have been equally noteworthy:

Today, some two years later, we have made tremendous progress. And that progress will contribute to the history of health care services in French. Now health care reform includes the Health System Integration Act. The four Ontario networks have finally succeeded in securing a Francophone planning entity. We are still at the discussion stage, but the fact remains that the four Ontario networks are likely to become planning entities recognized by the Ministry of Health. They will work closely with regional authorities responsible for developing funding plans. […]This is a major step forward for health services in French that would have been impossible had these networks not existed. So, it is a real success story.[65]

In Prince Edward Island, a representative from the provincial ministry of Acadian and Francophone affairs appeared before the Committee to describe the impact of these networks.

The Government of Prince Edward Island is a true partner of the Société Santé en français with regard to the work it carries out. Our government adopted a French-Language Services Act in 2000. We are now working to implement this legislation in order to ensure comparable high-quality services in all areas of government jurisdiction. The support of the Société Santé en français and the various existing funding components allow the Government of Prince Edward Island to meet its objective in a timely fashion.[66]

Cooperation has been equally productive at the other end of the country:

From the outset, we managed to mobilize all the components of the health system to develop programs, starting with the BC Health Guide, or Guide-santé Colombie-Britannique, in French. […] Our greatest success is without a doubt related to the fact that, as a result of that project, the department completely took charge of the ongoing distribution of the Francophone components of its program, while asking RésoSanté to continue its advisory role.[67]

In Nova Scotia, the health partnership with the provincial government is also considered one of the most positive outcomes of the Action Plan.

We have an excellent collaborative relationship with the Department of Health. I think I can say that it's more than collaboration. The network is having major success because it automatically includes the Department of Health. When network members have discussions, the department is already at the table. It's represented by the French-language services coordinator, who has been in that position since 2004.

So the network doesn't exist without the department. The department can exist without the network, but the latter doesn't exist without the department. The department has been there from the outset. […] This is a privileged relationship. I've never seen a similar relationship in any other area.[68]

The importance of strong cooperation with the provinces was established from the time the Société Santé en français was created:

The objectives were actually clearly identified from the outset: the projects had to improve accessibility, be sustainable and not just a flash in the pan, and provincial approval was necessary. This was an important requirement for approval, because Ottawa indicated it would not interfere in a provincial area of jurisdiction. So, provincial support was necessary. Each and every project, bar none, was approved by the provincial government.[69]

The representation of the federal and provincial governments in each network greatly facilitates monitoring and accountability as regards the results of the investments made by Health Canada.[70]

This view is shared by the stakeholders behind the Anglophone community networks in Quebec:

We have another priority. This priority is a partnership with the Quebec ministry of health and social services. Consequently, any investment made here, in Quebec, in the health care sector, must be part and parcel of the programs, plans, reorganizations, reforms and legislation of Quebec. The formula for our success lies in the great cooperation with our colleagues, here in Quebec.[71]

In the following section, we will look at the tangible benefits of the health component of the Action Plan for Official Languages, first as regards access to primary health care, and then as to the training and retention of health care professionals in minority communities.

The primary health care initiatives demonstrate the networks’ power. They show that community networks are once again the best way to identify the most pressing needs and the best way to meet them. The $30 million invested in the initial development of these networks generated at least four times more funding for the communities from provincial governments and local partners. The Committee is of the opinion that the leverage effect of investments by the federal government is a prime example of its catalyst role in fostering the vitality of official language minority communities.

Hubert Gauthier, President of Société Santé en français, gave the Committee an encouraging progress report on access to primary care, just three years after the creation of the networks. “I won't give you a scoop with regard to results, but we are headed in the right direction. The structures we have put into place are strong, and we can see an improvement of approximately five percent among the 55% of people who were deprived of services.”[72]

This is especially noteworthy since, among Francophone communities, the completion of the 67 projects selected by the networks under the Primary Care Transition Fund was stalled by Health Canada’s delay in releasing the funding required to get a number of projects going. This resulted in a loss of about $3 million in fiscal year 2004-2005, or about 10% of the total funding that the Société Santé en français and the networks had expected over five years.

For Anglophones in Quebec, very tangible results were achieved. “In this context, we can bear witness to the capacity of the Action Plan on Official Languages to achieve measurable and sustainable change. We have seen its effect in our community in the area of health and social services.”[73]

In each province and territory, initiatives have been taken to significantly improve the services offered compared to what was available before the networks were created. In order to be well received by the community, projects must be initiated by the community itself. The decision-making process established by the Société Santé en français is designed to root the initiatives in the community, for the long term:

The project starts therefore at a community level, before the province gets involved. A debate then ensues. A whole host of characters gathers around the negotiating table including professionals, regional boards, the provincial government, and the educational institutions. I was involved in the process when I was in Manitoba, and there were some solid debates. Is one project more important than another? Why? What are the reasons behind this? You can imagine the type of debate that such questions sparked given that there is never enough money for funding across the board. Once that stage is complete, the project is then considered at a national level by way of a review committee which goes over the details one last time with Health Canada. Once approved, service delivery contribution contracts are signed with Health Canada. And that is how it works. The groundwork is extremely important.[74]

In some provinces such as Saskatchewan, they basically had to start from scratch:

At first, our network had identified few French-language health care services provided to Franco-Saskatchewanians and little consistency in the health care services offered by the various providers. We have come a long way in three years' time.

First off, we identified health care professionals who could offer French-language services. Our research was successful because our directory now includes close to 150 names. Having checked, I can tell you that we now have 180 names on this list.[75]

In Southern Ontario, as in many other regions, community health centres are the best solution.

Community health centres go a long way toward addressing the needs of Francophones […] Moreover, our Anglophone partners still have to realize that if Francophones were served in their own language, it would free up the English-speaking system […] However, we are prepared to start with a 100% guarantee of bilingual services, that is, having Anglophones served in English and Francophones in French.[76]

The representatives from British Columbia were very enthusiastic about the recent opening of such a community health centre:

We're proud to announce the opening of a clinic, the Pender Community Health Centre in the eastern section of downtown Vancouver, which will soon be providing dedicated French-language services, where Francophones will be able to make appointments with doctors and other health professionals who will provide them with health care in French.[77]

Some regions are however experiencing persistent frustrations. This is the case in some communities in Northern Ontario:

It has been 15 years now that we, in Timmins, have been working to establish a Francophone community health centre […] There is a network, but what tangible effect does it have on citizens living in Timmins, who have to receive part of their health care services in English because there is no Francophone community health centre? In the field of health care, the Action Plan has had no tangible impact.[78]

For the Anglophone communities of Quebec, the results are equally impressive. With the $10 million invested through the Primary Health Care Transition Fund, 37 public institutions have improved their ability to serve Anglophones in their own language.

These projects were carried out over a 15-month period, ending in March 2006. Seven projects involved coordinating efforts to increase the use of Info-Santé, a telephone health line for English speakers. A new centralized telephone system was created in four regions with the investment. It will guarantee availability of such telephone services in English across Quebec, with extensive language training and translation of nursing protocols and social intervention guides.[79]

In addition to promoting Info-Santé, the Community Health and Social Services Network, together with the Quebec ministry of health and social services, has helped adapt the programs of local community service centres (CLSC) to the needs of dispersed or isolated Anglophone communities and create an environment suited to the Anglophone residents of some long-term health care centres.

Of course nothing is perfect and some regions have not benefited as much as others from federal investments. That said, the overall picture is still quite positive.

2.2.2.2.1. The Leverage Effect of Federal Funding

The catalyst effect of the networks was mentioned repeatedly by the witnesses and it acquired a strong symbolic value for a project in Manitoba, which illustrates perhaps better than any other one the importance of the federal government’s commitment.

In Notre-Dame-de-Lourdes, a Francophone majority community south of Winnipeg, a community centre is now being built.

Using a $30,000 grant, we studied the needs of the community based on the 12 health determinants. Next, we designed a primary health care centre. In addition to the $30,000 grant, the community raised $1.5 million for this project. As a result, the Government of Manitoba joined in and added $500,000. I will not name all the partners, because there are approximately 30 of them. Construction is currently underway […] I keep calling it a Francophone centre, but it is really a bilingual centre because, in Manitoba, it is clearly bilingual. I consider this an added value. We provide services in French, but we can certainly also provide them in English.[80]

This project has also had some unexpected benefits. For instance, the health centre in Notre-Dame-de-Lourdes will become a training centre for health care professionals. The success of this initiative has also garnered the attention of the Canada Health Infoway and of Télésanté Manitoba, which have included it in a pilot project on the use of new technologies to link the centre with the network of other community health centres. The construction of this centre is also part of a larger project that includes the establishment of satellite centres in the communities of Saint-Claude and Saint-Jean-Baptiste, and the creation of a mobile multi-disciplinary team serving the three communities.[81] All this with an initial federal investment of $30,000!

In addition to the direct spin-offs from the construction of the centre, this also illustrates the merits of what we might call the “Manitoba model,” which includes three service delivery models:

First there are community access centres like the one in Notre-Dame-de-Lourdes […] Second, there is the Telehealth program. We're installing equipment to connect the Francophone communities to the Telehealth network for the first time. This has never been done before back home. We were going to hook up small Anglophone villages near us, but we weren't reaching the Francophones.

With a little money from the projects of the FASSP, the primary health care adjustment fund, we could hook up eight Francophone communities in one year.

The third model is the mobile team model […] These teams consist of four or five health professionals who travel from village to village to serve the communities in the rural regions.[82]

The model appears to be very flexible and could possibly be used by other official language minority communities and many rural majority communities. It must be remembered, however, that the Francophone community of Manitoba benefits from a demographic density not found outside New Brunswick and the Montreal region.

2.2.2.2.2. Active Offer of Service

Other initiatives, both simple and effective, have been launched throughout the country. Immediate improvements were noted for instance as soon as very simple and inexpensive “active offer” measures were introduced:

Francophones, when they come to a large hospital that is primarily Anglophone, will not fight for services in French, because they fear they will get second-level service, if you will, or hear ‘stand in line, and we'll get somebody for you.’ They've stood in line long enough, and they don't want to do that. So they will compromise and go with the English services, even if half the time they're missing some pieces here.

Therefore, we created what we call the national brand to identify where services are available. It becomes more proactive. Staff have identification […] We've created that national service brand so that professionals can be identified and citizens know where service in French is available.[83]

Active offer can play an important role in people’s perceptions of service availability.

If you dial a toll-free 1-800 number and you are told to push 2 for services in French, it is clearly possible to obtain services in French. However, if you make a call and it is answered in English, the question probably does not even arise […] Actively offering services in a language undoubtedly has an impact on the perception people have of the possibility of receiving services in their language.[84]

The person who answered might have been bilingual, but without an active offer, the impression given is that service is not available. Conversely, institutions might perceive that their services are underutilized simply because clients do not realize they are available.

This situation is also evident among Anglophones in Quebec.

There is shyness, even if you're bilingual. […] you don't want to create some kind of supplementary demand on a very overstretched system, or you might be concerned that if you ask for a service in English, there may be a delay in getting that service.

Anglophones are less likely to go to a public institution to get a service to solve the problem. They stay in their communities, and often when they do hit the public system, they're in crisis at that point. But this is definitely a factor, even for bilingual Anglophones. They are intimidated by the environment of a public institution for which they do not feel any linguistic or cultural affinity.[85]

2.2.2.2.3. Providing Continuity

One of the chief concerns raised by the networks relates to the fact that the Primary Health Care Transition Fund, which funds official languages initiatives as well as various other projects across the country, expired in 2006. In other words, while Action Plan initiatives run from 2003 to 2008, those relating to primary health care ended two years earlier. At the end of 2005, the midterm report already identified the following risk:

The Official Languages component of the Primary Health Care Transition Fund will end in 2006, which could disrupt the organization of services and reduce the opportunities that form the basis for networking and professional training. The Préparer le terrain project has received the approval of all partners and its results, expected next year, will guide the balance of the Action Plan.[86]

Without any clear indication of the federal government’s intentions, the provincial governments will hesitate to assume full responsibility for projects developed in partnership. In Eastern Ontario, Préparer le terrain initiatives are already being discussed with regional health authorities:

The network set about developing the 2005-2006 regional plan for health services in French, a responsibility it was given by the Minister of Health and Long-Term Care. It was in this context that the Préparer le terrain project […] was managed by the network and integrated into the regional plan.

This important exercise generated a list of recommendations and priorities for French-language health services, which were presented to the local integration of health care services network for Champlain region in the fall of 2006. They are as follows: human resources, the organization of services, primary health care, accountability within the system and support for health care agencies in supplying French-language services.[87]

The witnesses who raised these concerns noted that their intention is not to encourage the federal government to take over from the provincial authorities, but simply to ensure that the provinces can effectively fulfill their constitutional responsibilities as regards the development of official language minority communities.

It would be unfortunate to have developed such fine projects under Préparer le terrain and then not to be able to carry them out due to a lack of federal government support which, as in other areas, can have a leverage effect and remind provincial governments of the role they are required to play in the development of official language minority communities.[88]

To provide short-term continuity for the projects developed and implemented with funding from the Primary Health Care Transition Fund, as intended when this component was incorporated into the Action Plan for Official Languages, the Committee recommends:

Recommendation 2

That Health Canada immediately confirm its commitment to provide a minimum of $10 million in funding for the initiatives under the “primary care transition” sub-component of the health component of the Action Plan for Official Languages, for fiscal year 2007-2008.

Given that the primary objective of creating networks in each province was to draw up a list of pressing needs and priority projects to be implemented so as to anticipate follow-up on the Action Plan, that the networks did this with great enthusiasm, and that the inability to carry out these projects would be a significant denial of the importance of providing long-term support to enable community networks to assume responsibility, the Committee recommends:

Recommendation 3

That as soon as possible Health Canada indicate its clear commitment to provide, through transfers to the provinces and territories, the networks coordinated by the Société Santé en français and the Community Health and Social Services Network the resources needed to carry out the key initiatives identified under Préparer le terrain projects, in the form of increased long-term funding, starting in fiscal year 2008-2009.

There is a significant shortage of trained health care workers in all parts of Canada, but the problem is much greater for minority communities, given their limited resources and the very few institutions that can offer training comparable to what is offered to the majority. In some cases, the situation is truly critical. In this regard, Anglophones in Quebec are in a good position, despite the difficulties they face in retaining graduates since they have access to a number of excellent teaching institutions. Apart from New Brunswick and Eastern Ontario, Francophones are very far from having access to training comparable to what is available to the Anglophone majority.

With respect to training, the Action Plan’s results are not felt as quickly in the communities as they are for other components given the length of professional training, which can last for two or three years for technical training, but up to eight years for a physician. Of the $75 million invested in the training and retention of health professionals, $63 million went to the Consortium national de formation en santé, which manages the programs for Francophone communities, and $12 million went to McGill University, which coordinates second-language learning programs for health professionals in Quebec. In both cases, a long-term commitment from the federal government is essential to success.

This relative advantage enjoyed by Anglophones in Quebec was recognized and accepted by Anglophone communities themselves, and led to different priorities, with a focus on language training, which are less expensive than long-term training for Francophones outside Quebec.

McGill University is the lead organization and is working with the 76 health organizations in the province of Quebec. Anglophones are currently developing initiatives to recruit and retain Anglophone health personnel in the province of Quebec. Huge efforts are being made to help professionals acquire a second language. Anglophones are learning a bit more French, and Francophones are learning a bit more English, which will help them treat English-speaking patients. […] In the province of Quebec, 37 Anglophone projects have been funded. All these projects are designed in a manner that will improve access, accountability and the integration of services with provincial and territorial services.[89]

In 2005-2006, 1,400 French-speaking health professionals were trained in order to better serve English-speaking clients, in 81 public institutions and 15 administrative regions in Quebec. In fiscal year 2006-2007, about 2,000 more Francophone health professionals will have received this training focussing on medical vocabulary.

In order to help retain Anglophone health professionals outside Montreal, “22 innovative pilot partnerships have been struck in 14 regions to create internships to increase the number of English-language students in nursing, social work and other health-related disciplines that receive professional training in the regions.”[90]

The problem of retaining graduates is significant throughout Quebec, but especially in the Outaouais region.

Heritage College in the Outaouais trains nurses who can practice their profession in English. Yet, about 80 per cent of these nurses leave the Outaouais and go to Ontario or elsewhere in the country to practice. One reason they leave is because they don’t feel adequately equipped to offer services in both official languages. So, as part of the program instituted in collaboration with McGill University, these students will receive training in their second language adapted to the health environment in French.[91]

The Committee strongly supports the efforts made by McGill University, together with the Government of Quebec, public institutions and the Community Health and Social Services Network, and recommends:

Recommendation 4

That Health Canada renew and increase its long-term funding for the language training programs currently coordinated by McGill University under the “training and retention” sub-component of the health component of the Action Plan for Official Languages, starting in fiscal year 2008-2009.

2.2.2.3.2. Consortium National de Formation en Santé (CNFS)

The CNFS comprises ten universities and colleges throughout Canada that offer French-language programs of study in various areas of health care. Its ten members are:

§ Sainte Anne University (Nova Scotia);

§ Université de Moncton;

§ French-language medical training program of New Brunswick, affiliated with Sherbrooke University;

§ New Brunswick Community College - Campbellton;

§ Collège universitaire de Saint-Boniface;

§ Saint-Jean Campus (Edmonton);

§ Laurentian University (Sudbury);

§ Collège Boréal (Sudbury);

§ University of Ottawa;

§ Cité collégiale (Ottawa).

These ten institutions share total funding of $63 million under the workforce training and retention sub-component of the Action Plan for Official Languages. The objective of the CNFS is to increase the presence and contribution of Francophone health professionals and researchers in order to better address the needs of Francophone minority communities.

Before signing bipartite agreements with Health Canada, each institution first had to indicate the additional enrolment expected as a result of the federal investments. The CNFS was also required to identify placements after which graduates could return to minority communities.

Cité collégiale for example signed an agreement with Health Canada valued at $4.3 million over five years, in exchange for which it promised a specific number of extra students, graduates and placements over five years.[92] These placements are crucial to retaining health care professionals.

We determined that 75 % of students who do their internships at local hospitals are hired to stay on after they graduate. That way, students return to their communities of origin. These new sites for clinical placements are crucial as regards regional retention.[93]

In many respects, the results are spectacular and greatly exceed initial expectations.

The project has resulted in 1,428 new enrolments, which is 33% over the expected results, and almost 300 new graduates, which is 32% over the expected results.

The participating institutions made a commitment to develop and launch a total of 20 new programs during Phase II. They have already launched 16 and expect to launch a total of 28 by the end of 2008. With respect to the development of placement settings, which is key to the success of the CNFS project, CNFS has managed to develop 200 new placements. As far as our goal was concerned, we are 100% ahead of schedule.[94]

The CNFS could also make a significant contribution to the international recruitment of health care professionals by developing qualification recognition programs, together with provincial governments.

A project valued at a million dollars was presented by the consortium to provide additional training for physicians who trained abroad so they can practise in Canada. The program is not up and running yet, but there have been discussions and commitments have been made.[95]

Despite these significant successes, there are still tremendous challenges. The case of Manitoba is a telling example.

This year, eight doctors are in training, in unusual circumstances. Some are studying in English at the University of Manitoba, others at the University of Ottawa. In addition, two doctors are in training at the University of Sherbrooke. We've calculated that roughly 14 would have to be trained each year for us to be able to hope, within 20 or 25 years, to provide half of the frontline medical services required, that is, in family medicine. We've made good progress, but it's barely enough to offset departures.[96]

The strength of the CNFS is in large part its ability to form partnerships among French-language institutions. In Nova Scotia, for instance:

Through the CNFS, we've managed to put certain programs in place at the college level, including a paramedic-ambulance care program. In the past four years, we've managed to train 50 ambulance attendants. So we have 50 Francophone paramedic-ambulance attendants who are ready to enter the system as soon as the regulations are in place. This is one of the areas where we've had good success.[97]

This cooperation among institutions prevents the costly duplication of administrative structures for programs and allows more flexibility to adapt programs in order to better meet the needs of minority communities as compared to the unwieldy programs established where warranted by demographics:

We do not want to set up a program in medicine at Collège universitaire de Saint-Boniface. Similarly, we do not necessarily want to create a physiotherapy program at Collège Saint-Jean. What we want is to work in partnership with these institutions.[98]

Phase III of CNFS Projects

The funding of training and retention activities under the Action Plan for Official Languages from 2003 to 2008 constituted Phase II of the CNFS. Obtaining funding as of fiscal year 2008-2009 would launch Phase III, which would end in 2013-2014.

The primary objective of Phase III would be to continue training and build training capacity for existing programs, to evaluate these programs and to make any necessary adjustments, including improved tracking of students after graduation. Priority would be given to the training of front-line professionals in order to strengthen the initiatives of Société Santé en français. The second objective would be the upgrading of health professionals trained in French five or ten years ago. In minority communities, such upgrading is usually only available in English. The third objective is recognition of immigrants’ foreign qualifications.

We have to be able to welcome and guide throughout the process new immigrants who already have training in health care. If they receive nursing training in a country other than Canada and the professional bodies do not recognize them directly, we have to be able to give them complementary training to allow them to work as soon as possible in their Francophone minority area.[99]

The initial estimates show that a substantial increase in the federal investment would be required for Phase III.

Just to fulfill our existing commitments, we need about $85 million. We will probably submit a proposal for about $125 million to $130 million over five years. I think that amount is fully justifiable. We intend to submit the proposal with much interest and enthusiasm sometime in March or April 2007.[100]

The Committee members wish to show their openness to supporting the work of the CNFS and recognize the results achieved by recommending that the federal government accept the proposal put forward by the CNFS for Phase III. Given the significant amount of funding involved though we must proceed carefully and take certain precautions, which do not in any way call into question the program’s validity.

Sharing of Responsibilities

One of the great achievements of the networks developed under Société Santé en français is that the provinces and territories are now included in the decision-making process that starts in the communities. These governments by contrast are not part of CNFS activities: “In fact, the Canadian cooperation that has allowed interprovincial exchanges is not something that naturally occurs in areas under provincial jurisdiction. This is not done. This is not something that is necessarily considered as desirable.”[101] In fact, one of the major achievements of the networking and primary care transition activities is to have demonstrated the opposite.

Agreements for significant amounts are signed directly between the training institutions and the federal government. This raises the concern that the federal government is taking the place of the provincial governments, whether or not the latter tolerate or benefit from this. The nature and extent of the federal government’s involvement in these projects have not been sufficiently clarified and care must but taken to avoid any appearance of the provincial governments’ responsibility for official language minority communities slowly being transferred to the federal government. The Committee agrees that it should ideally cost the provincial governments less to train a Francophone health care professional than an Anglophone one in order for the provinces to become actively involved in the development of official language minority communities. The cost to the provinces must nevertheless not be too low. The comments of the co-chair of the CNFS address this concern indirectly:

In the case of a Franco-Ontarian studying at the University of Ottawa, but not within the framework of the CNFS, no effort is made to organize training placements for that student in Windsor, northern Ontario or in Niagara. Nonetheless, I think that the federal government has a duty to serve all these minority communities, to fund Laurentian University, the University of Ottawa, Cité collégiale, Boreal College, these four member institutions of the CNFS, so that we can make an additional effort to encourage these students to go back to their home region. That is where the CNFS plays an important role. In this context, this becomes a federal responsibility.[102]

The federal government’s current investment amounts to approximately $60,000 per student under the CNFS. At first glance, it seems expensive to fund the additional “effort to encourage students to return to their communities of origin”. This investment must not absolve the provincial governments of their responsibilities and must not be used to directly compensate institutions over and above the cost to them of making this extra effort, especially since the provinces are not represented on the CNFS Board of Directors, and the federal government is an associate member only.

Financial Data

This caveat is in large part due to the fact that no financial analysis has been done of CNFS activities. This does not reflect any judgement by the members of the Committee, but rather suggests that greater accountability might be in order given the significant amounts involved. This problem is not as significant for networking and primary care transition activities, since the provinces and the federal government are partners in the decision-making process. The comments by the CNFS are clearly intended to provide some reassurance.

What I would like is perhaps to do another presentation for the government to say that if subsidies are linked to financial responsibility, then it owes us money. We have trained more students, in fact 30% to 40% more, than we set out to do. There is a responsibility — and I totally agree with this concept within universities — to ensure that the money received from the federal government, which comes from taxpayers, is well spent and that we can show specific projects in return for the money we are given.

That is why we proceeded with this evaluation exercise midway through Phase II of the health research and training project.[103]

The problem is that this midterm evaluation did not include a financial analysis and sought instead primarily to report on the increase in enrolment, graduates and placements at each CNFS member institution.

Participation of All Provinces

Despite the various cooperation agreements among training institutions, the provinces of Newfoundland and Labrador, Prince Edward Island, Saskatchewan[104] and British Columbia do not have any CNFS member institutions:

In Prince Edward Island, the Francophone postsecondary institution, the Société éducative de l'Île-du-Prince-Édouard, is not a full-fledged member of the Consortium national de formation en français, the CNFS. Until it becomes one, we'll be facing major barriers to the training and retention of health professionals.[105]

It would be helpful if all the provinces and territories had a representative on the CNFS board in order to state their specific health care training needs.

Beyond these caveats, the Committee fully recognizes the tremendous long-term benefits of CNFS projects and firmly believes that these benefits must be supported by providing a renewed financial commitment in the long-term.[106] The Committee therefore recommends:

Recommendation 5

Subject to:

§ clarification of the respective responsibilities of member institutions, provincial and territorial governments and the federal government;

§ an in-depth evaluation of the use of the funding allocated in order to compare the cost of training a student outside the CNFS to that of training a student within the CNFS;

§ and finally including a spokesperson from each province and territory on the CNFS Board of Directors.

That Health Canada show openness to the funding proposal to be submitted in 2007 by the Consortium national de formation en santé (CNFS) for Phase III of its projects extending from 2008-2009 to 2013-2014.

[30] Consultative Committee for French-Speaking Minority Communities, Report to the Federal Minister of Health, September 2001.

[31] FCFA, Pour un meilleur accès à des services de santé en français, 2001. Available online at http://www.fcfa.ca/media_uploads/pdf/82.pdf.

[32] Ibid. p. 6.

[33] Louise Bouchard (Professor, Director, PhD Program in Population Health, University of Ottawa, October 19, 2006, 10:45 a.m.

[34] Jean-Pierre Corbeil (Senior Population Analyst, Demography Division, Statistics Canada), Evidence, October 17, 2006, 9:55 a.m.

[35] Louise Bouchard (Professor, Director, PhD Program in Population Health, University of Ottawa), October 19, 2006, 9:25 a.m.

[36] Forgues, Éric, M. Beaudin and N. Béland, L’évolution des disparités de revenu entre les francophones et les anglophones du Nouveau-Brunswick de 1970 à 2000, Canadian Institute for Research on Linguistic Minorities, Moncton, October 2006, p. 24.

[37] Hubert Gauthier (President and Director General, Société Santé en français), Evidence, October 5, 2006,

10:30 a.m.

[38] Louise Bouchard (Professor, Director, PhD Program in Population Health, University of Ottawa), Evidence, October 19, 2006, 9:30 a.m.

[39] Hubert Gauthier (President and Director General, Société Santé en français), Evidence, October 5, 2006,

9:10 a.m.

[40] Louise Bouchard (Professor, Director, PhD Program in Population Health, University of Ottawa), October 19, 2006, 9:20 a.m.

[41] Consultative Committee for French-Speaking Minority Communities, Report to the Federal Minister of Health, September 2001.

[42] FCFA, Pour un meilleur accès à des services de santé en français, 2001. Available online at: http://www.fcfa.ca/media_uploads/pdf/82.pdf.

[43] Ibid, p. 24.

[44] Ibid. p. 25.

[45] Ibid. p. 13.

[46] Jean-Pierre Corbeil (Senior Population Analyst, Demography Division, Statistics Canada), Evidence, October 17, 2006, 9:10 a.m.

[47] Cyrilda Poirier (Acting Director General, Fédération des francophones de Terre-Neuve et du Labrador), Evidence, November 6, 2006, 11:15 a.m.

[48] Alphonsine Saulnier (President, Réseau santé Nouvelle-Écosse), Evidence, November 7, 2006, 11:00 am.

[49] Gilles Vienneau (Director General, Société santé et mieux-être du Nouveau-Brunswick), Evidence, November 7, 2006, 2:15 p.m.

[50] Hubert Gauthier (President and Director General, Société Santé en français), Evidence, October 5, 2006,

9:35 a.m.

[51] Nicole Robert (Director, French Language Health Services Network of Eastern Ontario), Evidence, October 19, 2006, 9:10 a.m.

[52] Soraya Côté (Director, Réseau santé en français de la Saskatchewan), Evidence, December 6, 2006, 9:55 am; see also Denis Desgagné (Director General, Assemblée communautaire fransaskoise), Evidence, December 6, 2006, 9:15 a.m.

[53] Jean-Gilles Pelletier (Director General, Centre francophone de Toronto), Evidence, November 9, 2006, 9:20 a.m.

[54] Marc-André Larouche (Director General, Réseau des services de santé en français du Moyen-Nord de l'Ontario), Evidence, November 10, 2006, 9:45 a.m.

[55] Michel Tétreault (President and CEO, Saint Boniface General Hospital), Evidence, December 6, 2006, 7:25 p.m.

[56] Denis Vincent (President, Réseau santé albertain), Evidence, December 5, 2006, 8:35 a.m.

[57] Brian Conway (President, RésoSanté de la Colombie-Britannique), Evidence, December 4, 2006, 10:20 a.m.

[58] Roger Farley (Executive Director, Official Language Community Development Bureau, Intergovernmental Affairs Directorate, Health Canada), Evidence, October 26, 2006, 10:05 a.m.

[59] Marcel Nouvet (Assistant Deputy Minister, Health Canada), Evidence, October 26, 2006, 9:25 a.m.

[60] Jean-Pierre Corbeil (Senior Population Analyst, Demography Division, Statistics Canada), Evidence, October 17, 2006, 9:55 a.m.

[61] Jean-Pierre Corbeil (Senior Population Analyst, Demography Division, Statistics Canada), Evidence, October 17, 2006, 9:10 a.m.

[62] Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages, Annual Report 2005-2006, p. 58.

[63] Marc-André Larouche (Director General, Réseau des services de santé en français du Moyen-Nord de l'Ontario), Evidence, November 10, 2006, 9:55 a.m.

[64] Denis Fortier (Administrator, Member of the Board of Directors, Regional Health Authority, Central Manitoba, Société Santé en français), Evidence, October 5, 2006, 9:20 a.m.

[65] Marc-André Larouche (Director General, Réseau des services de santé en français du Moyen-Nord de l'Ontario), Evidence, November 10, 2006, 9:20 a.m.

[66] Donald DesRoches (Administrator, Member of the Board of Directors, Delegate of the Minister for Acadian and Francophone Affairs of Prince Edward Island, Société Santé en français), Evidence, October 5, 2006, 9:25 a.m.

[67] Brian Conway (President, RésoSanté de la Colombie-Britannique), Evidence, December 4, 2006, 10:20 a.m.

[68] Alphonsine Saulnier (President, Réseau santé Nouvelle-Écosse), Evidence, November 7, 2006, 11:20 a.m.

[69] Hubert Gauthier (President and Director General, Société Santé en français), Evidence, October 5, 2006, 10:35 a.m.

[70] Marcel Nouvet (Assistant Deputy Minister, Health Canada), Evidence, October 26, 2006, 10:15 a.m.

[71] James Carter (Coordinator, Community Health and Social Services Network), Evidence, November 8, 2006, 10:00 a.m.

[72] Hubert Gauthier (President and Director General, Société Santé en français), Evidence, October 5, 2006, 9:45 a.m.

[73] Michael Van Lierop (President, Townshippers Association), Evidence, November 8, 2006, 9:20 a.m; see also comments by James Carter (Coordinator, Community Health and social Services Network) Evidence, November 8, 2006, 9:05 a.m.

[74] Hubert Gauthier (President and Director General, Société Santé en français), Evidence, October 5, 2006, 10:35 a.m.

[75] Roger Gauthier (Elected Member and Treasurer, Réseau santé en français de la Saskatchewan), Evidence, December 6, 2006, 9:00 a.m.

[76] Nicole Rauzon-Wright (President, Réseau franco-santé du Sud de l'Ontario), Evidence, November 9, 2006, 9:45 a.m.

[77] Brian Conway (President, RésoSanté de la Colombie-Britannique), Evidence, December 4, 2006, 11:10 a.m.

[78] Pierre Bélanger (Chair of Board of Directors, Alliance de la francophonie de Timmins), Evidence, November 8, 2006, 10:20 a.m.

[79] James Carter (Coordinator, Community Health and Social Services Network), Evidence, November 8, 2006, 9:10. a.m.

[80] Denis Fortier (Administrator, Member of Board of Directors, Regional Health Authority, Central Manitoba), Evidence, October 5, 2006, 9:20 a.m

[81] Charles Gagné (President, Conseil communauté en santé du Manitoba), Evidence, December 6, 2006, 7:05 p.m.

[82] Léo Robert (Director General, Conseil communauté en santé du Manitoba), Evidence, December 6, 2006, 7:45 p.m.

[83] Hubert Gauthier (President and Director General, Société Santé en français), Evidence, October 5, 2006, 10:05 a.m.

[84] Jean-Pierre Corbeil (Senior Population Analyst, Demography Division, Statistics Canada), Evidence, October 17, 2006, 10:10 a.m.

[85] James Carter (Coordinator, Community Health and Social Services Network), Evidence, November 8, 2006, 10:10 a.m.

[86] Midterm Report on the Action Plan for Official Languages, pp. 17-19.

[87] Nicole Robert (Director, French Language Health Services Network of Eastern Ontario), Evidence, October 19, 2006, 9:10 a.m.

[88] Norman Gionet (President, Société santé et mieux-être du Nouveau-Brunswick), Evidence, November 7, 2006, 13:15 a.m.

[89] Marcel Nouvet (Associate Deputy Minister, Health Canada), Evidence, November 26, 2006, 9:10 a.m.

[90] James Carter (Coordinator, Community Health and Social Services Network), Evidence, November 8, 2006, 9:10 a.m.

[91] Roger Farley (Executive Director, Official Language Community Development Bureau, Intergovernmental Affairs Directorate, Health Canada), Evidence, October 26, 2006, 9:30 a.m.

[92] Andrée Lortie (President, La Cité Collégiale), Evidence, October 24, 2006, 9:50 a.m.

[93] Andrée Lortie (President, La Cité Collégiale), Evidence, October 24, 2006, 9:10 a.m.

[94] Gilles Patry (Co-Chair, Consortium national de formation en santé), Evidence, October 31, 2006, 9:05 a.m.

[95] Roger Farley (Executive Director, Official Language Community Development Bureau, Intergovernmental Affairs Directorate, Health Canada), Evidence, October 26, 2006, 10:10 a.m.

[96] Michel Tétreault (President and Director General, Saint Boniface General Hospital) Evidence, December 6, 2006, 7:25 p.m.

[97] Alphonsine Saulnier (President, Réseau santé Nouvelle-Écosse), Evidence, November 7, 2006, 11:05 a.m.

[98] Gilles Patry (Co-Chair, Consortium national de formation en santé), Evidence, October 31, 2006, 9:40 a.m.

[99] Ibid., at 9:45 a.m.

[100] Ibid., at 10:20 a.m.

[101] Andrée Lortie (President, La Cité Collégiale), Evidence, October 24, 2006, 9:25 a.m.

[102] Gilles Patry (Co-Chair, Consortium national de formation en santé), Evidence, October 31, 2006, 9:55 a.m.

[103] Gilles Patry (Co-Chair, Consortium national de formation en santé), Evidence, October 31, 2006, 9:35 a.m

[104] The Institut français of the University of Regina is an associate member.

[105] Jeannita Bernard (Member, Prince Edward Island French Language Health Services Network), Evidence, November 7, 2006, 9:15 a.m.

[106] This renewal would continue the commitments in the Ten-Year Plan to Strengthen Health Care, released in September 2004. This plan states that the Government of Canada commits to: accelerate and expand the assessment and integration of internationally trained health care graduates; targeted efforts in support of Aboriginal communities and Official Languages Minority Communities to increase the supply of health care professionals for these communities; measures to reduce the financial burden on students in specific health education programs; and participate in health human resource planning with interested jurisdictions. “A 10-Year Plan to Strengthen Health Care,” September 16, 2004, available at http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hcs-sss/delivery-prestation/fptcollab/2004-fmm-rpm/nr-cp_9_16_2_e.html