Chapter 12The Process of Debate

Moving a Motion

A Member initiates the process of debate in the Chamber by moving (i.e., proposing) a motion. When notice of a motion has been given, the Speaker will first ensure that the Member wishes to proceed with the moving of the motion. If the sponsor of a motion chooses not to proceed (either by not being present221 or by being present but declining to move the motion222), then the motion is not proceeded with and is dropped from the Order Paper, unless allowed to stand at the request of the government.223 If the sponsor wishes to proceed and nods in agreement, the Speaker then ascertains whether there is a seconder. All motions in the House require a seconder;224 if none is found, the Speaker will not propose the question to the House and no entry will appear in the Journals as the House is not in possession of it.225 Any Member may act as a seconder, even for government motions which may be moved only by Ministers.226 If the seconder should cease to be a Member of the House after the motion has been duly proposed, the motion remains in order.227 Once a motion is moved and seconded, it is still not properly before the House and may not be debated until it has been proposed (i.e., read out from the Chair).228

The moving of a motion which does not require notice typically ends the speech in which it is included.229 Before recognizing another Member on debate, the Speaker first asks if there is a seconder for the motion.230 If there is a seconder, and after the motion is received in writing and found procedurally in order, the Speaker then reads it out from the Chair, thus proposing it to the House.

The requirement that a motion be in writing applies to all motions, whether or not they require notice, as well as to amendments and subamendments, both in the House and its committees. In the House, when notice of a motion has been given, the requirement that it be in writing is automatically met since the text of the motion appears on the Order Paper. In all other instances in which the motion does not appear on the Order Paper or has not been published and distributed to Members, the Speaker must receive a written copy of the motion before proposing it to the House prior to debate. The Member will also append his or her signature to the text of the motion.

Before reading a motion to the House, it is the Speaker’s duty to ensure that it is procedurally in order. This is done by verifying that the notice requirement, if any, has been met, that the wording of the motion corresponds to that of the notice, and that the motion contains no objectionable or irregular wording. Any part of a motion found out of order will render the whole motion out of order.231 If the Chair finds the form of the motion to be irregular, he or she has the authority to modify it in order to ensure that it conforms to the usage of the House.232 This is usually done with the concurrence of the mover.233 If a motion is ruled out of order, a Member may move it again after the necessary corrections have been made and the notice requirements have been met; it is then treated as a new motion.

In ruling a motion out of order, the Speaker informs the House of the reasons for this and cites the Standing Order or authority applicable to the case.234 The motion is not proposed to the House and is dropped from the Order Paper.

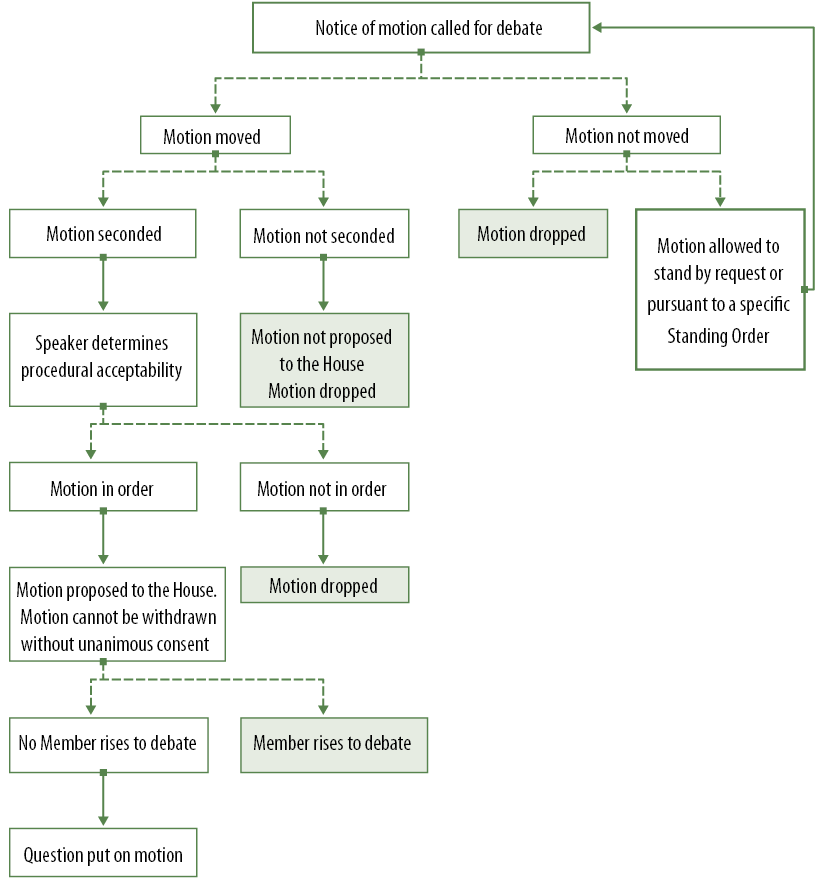

If the motion is found to be in order, and has been moved and seconded, the Speaker proposes it to the House. Once the Speaker has read the motion in the words of its mover, it is considered to be before the House. Every motion found to be in order and proposed from the Chair is entered in the Journals (see Figure 12.2, “Moving a Motion”).

The rules of the House require that the motion be read in English and in French by the Speaker (or by the Speaker and the Clerk if the former is not familiar with both languages).235 However, this requirement has become anachronistic, given the existence of simultaneous interpretation on the floor of the House.236 Likewise, the requirement that all motions be read in their entirety is regularly waived, particularly for lengthy motions and given the immediate availability of the text of the motion in both official languages on the Order Paper or Notice Paper. The Speaker will read the first few words and then ask, “Shall I dispense (with reading the entire text)?”, to which the response from Members is usually in the affirmative.237 When a motion does not appear on the Order Paper or has not been published and distributed, Members may request at any time during debate that the Chair read it aloud, so long as no Member speaking to the matter is thereby interrupted.238

After a motion has been proposed to the House, the Speaker recognizes the mover as the first to speak in debate. If the mover chooses not to speak, he or she is nonetheless deemed to have spoken (by nodding, the Member is considered to have said “I move” and this is taken as the equivalent of speech in the debate).239 The Member who seconds a motion is not required to speak to it at this point, but may choose to do so later in the debate. The one exception occurs during the debate on the Address in Reply to the Speech from the Throne, when it is traditional for the seconder to be recognized to speak immediately after the mover has spoken.240

The Rule of Anticipation

The moving of a motion was formerly subject to the ancient “rule of anticipation” which is no longer strictly observed. According to this rule, which applied to other proceedings as well as to motions, a motion could not anticipate a matter which was standing on the Order Paper for further discussion, whether as a bill or a motion, and which was contained in a more effective form of proceeding.241 For example, a bill or any other Order of the Day is more effective than a motion, which in turn has priority over an amendment, which in turn is more effective than a written or oral question. If such a motion were allowed, it could indeed forestall or block a decision from being taken on the matter already on the Order Paper.

While the rule of anticipation is part of the Standing Orders in the British House of Commons, it has never been so in the Canadian House of Commons. Furthermore, references to past attempts to apply this British rule to Canadian practice are inconclusive.242

The rule is dependent on the principle which forbids the same question from being decided twice within the same session. It does not apply, however, to similar or identical motions or bills which appear on the Notice Paper prior to debate.243 The rule of anticipation becomes operative only when one of two similar motions on the Order Paper is actually proceeded with.244 For example, two bills similar in substance will be allowed to stand on the Order Paper but only one may be moved and disposed of. If a decision is taken on the first bill (for example, to defeat the bill or advance it through a stage in the legislative process), then the other may not be proceeded with. If the first bill is withdrawn (by unanimous consent, often after debate has started), then the second may be proceeded with. A point of order regarding anticipation may be raised when the second motion is proposed from the Chair, if the first has already been proposed to the House and has become an Order of the Day.

An exception has been allowed, however, in the case of an opposition motion on a supply day related to the subject matter of a bill already before the House. Under the normal application of the rule, the Chair would refuse the motion because it ranks as inferior to a bill. The Speaker has nonetheless ruled that the opposition prerogative in the use of an allotted day is very broad and ought to be interfered with only on the clearest and most certain of procedural grounds.245

At one time, Members were also prohibited from asking a question during Question Period if it was in anticipation of an Order of the Day; this was to prevent the time of the House being taken up with business to be discussed later in the sitting.246 In 1975, the rule was relaxed in regard to questions asked during Question Period when the Order of the Day was either the budget debate or the debate on the Address in Reply to the Speech from the Throne, as long as questions on these matters did not monopolize the limited time available during Question Period.247 In 1983, the Speaker ruled that questions relating to an opposition motion on a supply day could also be put during Question Period.248 In 1997, the Standing Committee on Procedure and House Affairs recommended, in a report to the House, that questions not be ruled out of order on this basis alone.249 The Speaker subsequently advised the House that the Chair would follow the advice of the Committee.250

Withdrawal of Motion

Once a motion has been proposed from the Chair, it is in the possession of the House and may be debated. A Member who has moved a motion may request that it be withdrawn, but this can be done only with the unanimous consent of the House.251 If no dissenting voice is heard, the Speaker declares the motion withdrawn and an entry to that effect appears in the Journals. Any motion thus withdrawn may again be put on notice and moved at a later date,252 at which time it will be treated as a new motion. The mover of an amendment or a subamendment may similarly seek consent to effect its withdrawal.253

Unanimous consent may be sought to alter or replace a motion, an amendment or a subamendment with another254 as long as no amendment or subamendment to the former is before the House. Members have also received the consent of the House for the withdrawal of motions (or amendments) moved by other Members.255

Since “withdrawal” removes a motion from any further consideration that has been ordered (as in the case of a bill awaiting second reading), the existing order of the House must first be discharged.256 Thus, the House must consent both to the discharge of the order and to the withdrawal of the item.

Dividing a Motion

When a complicated motion comes before the House (for example, a motion containing two or more parts each capable of standing on its own), the Speaker has the authority to modify it in order to facilitate decision making in the House. When any Member objects to a motion containing two or more distinct propositions, he or she may request that the motion be divided and that each proposition be debated and voted on separately. The final decision, however, rests with the Chair. On a related matter, the Speaker has ruled that the practice of dividing substantive motions has never been extended to bills and that the Chair has no authority to do the latter.257

The matter of dividing a complicated motion has arisen in the House on at least six occasions. In 1964, a complicated government notice of motion was divided and restated when the Speaker found that the motion contained two propositions which many Members objected to considering together.258 In 1966, faced with a similar request, the Speaker ruled against taking such an action, stating that only in exceptional circumstances should the Chair make this decision on its own initiative.259 In 1991, in response to a request to divide a motion dealing with proposed amendments to the Standing Orders, the Speaker undertook discussions with the leadership of the three parties in the House, subsequently ruling that, for voting purposes, the motion would be divided into three groupings, in addition to the paragraphs relating to the coming into force of the motion.260 In 2002, objections to a complicated motion for the reinstatement of government business prompted the Speaker to divide it into two separate motions, the first of which was further subdivided into two sections for voting purposes.261 In 2006, with the unanimous consent of the House, the Speaker was given the authority to divide any amendment to a motion concerning Senate amendments to a government bill for voting purposes and after consultation with the parties.262 In 2013, the Speaker directed that one part of a government motion be voted on separately while allowing the motion to be debated as a whole.263 In 2017, the Standing Orders were amended to give the Speaker, in the case of a government bill seeking to repeal, amend or enact more than one act, and where there is not a common element connecting the various provisions or where unrelated matters are linked, the power to divide the questions, for the purpose of voting, on the motion for second reading and reference to a committee and the motion for third reading and passage of the bill. The Speaker has the power to combine clauses of the bill thematically and put the aforementioned questions on each of these groups or clauses separately but in keeping a single debate at each stage.264