|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

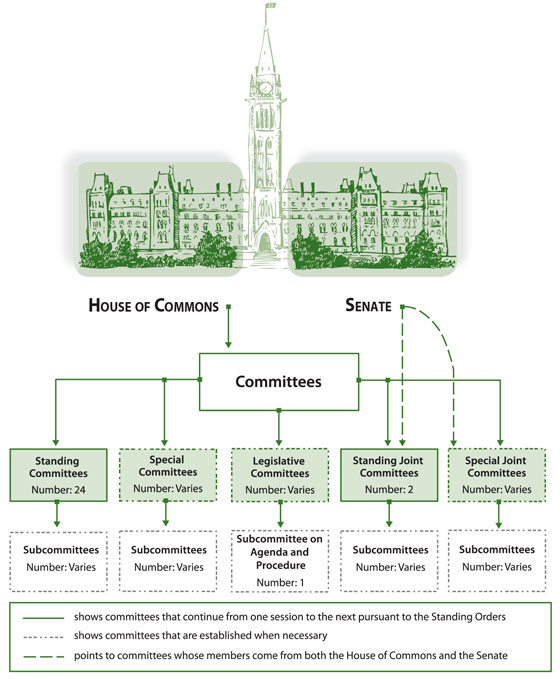

The House of Commons has an extensive committee system. There are various types of committees: standing, standing joint, legislative, special, special joint and subcommittees.[54] They differ in their membership, the terms of reference they are given by the House, and their longevity. Figure 20.1 illustrates the various types of committees and their characteristics.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

* As provided in the Standing Orders of the House of Commons

General Mandate

The Standing Orders set out a general mandate for all standing and standing joint committees, with a few exceptions.[58] They are empowered to study and report to the House on all matters relating to the mandate, management, organization and operation of the departments assigned to them. More specifically, they can review:

![]() the

statute law relating to the departments assigned to them;

the

statute law relating to the departments assigned to them;

![]() the

program and policy objectives of those departments, and the effectiveness of

their implementation thereof;

the

program and policy objectives of those departments, and the effectiveness of

their implementation thereof;

![]() the

immediate, medium and long-term expenditure plans of those departments and the

effectiveness of the implementation thereof; and

the

immediate, medium and long-term expenditure plans of those departments and the

effectiveness of the implementation thereof; and

![]() an

analysis of the relative success of those departments in meeting their

objectives.

an

analysis of the relative success of those departments in meeting their

objectives.

In addition to this general mandate, other matters are routinely referred by the House to its standing committees: bills, estimates, Order-in-Council appointments, documents tabled in the House pursuant to statute, and specific matters which the House wishes to have studied.[59] In each case, the House chooses the most appropriate committee on the basis of its mandate.

Specific Mandates

The Standing Orders set out specific mandates for some standing committees, on the basis of which they are to study and report to the House:

![]() The

Standing Committee on Procedure and House Affairs deals with, among

other matters, the election of Members; the administration of the House and the

provision of services and facilities to Members; the effectiveness, management

and operations of all operations which are under the joint administration and

control of the two Houses, except with regard to the Library of Parliament; the

review of the Standing Orders, procedure and practice in the House and its

committees;[60]

the consideration of business related to private bills; the review of the radio

and television broadcasting of the proceedings of the House and its committees;

the Conflict of Interest Code for Members of the House of Commons; and the

review of the annual report of the Conflict of Interest and Ethics Commissioner

with respect to his or her responsibilities under the Parliament of Canada

Act.[61]

The Committee also acts as a striking committee, recommending the list of members

of all standing and legislative committees, and the Members who represent the

House on standing joint committees.[62]

It also establishes priority of use of committee rooms,[63] and is involved in designating

the items of Private Members’ Business as votable or non-votable.[64]

The

Standing Committee on Procedure and House Affairs deals with, among

other matters, the election of Members; the administration of the House and the

provision of services and facilities to Members; the effectiveness, management

and operations of all operations which are under the joint administration and

control of the two Houses, except with regard to the Library of Parliament; the

review of the Standing Orders, procedure and practice in the House and its

committees;[60]

the consideration of business related to private bills; the review of the radio

and television broadcasting of the proceedings of the House and its committees;

the Conflict of Interest Code for Members of the House of Commons; and the

review of the annual report of the Conflict of Interest and Ethics Commissioner

with respect to his or her responsibilities under the Parliament of Canada

Act.[61]

The Committee also acts as a striking committee, recommending the list of members

of all standing and legislative committees, and the Members who represent the

House on standing joint committees.[62]

It also establishes priority of use of committee rooms,[63] and is involved in designating

the items of Private Members’ Business as votable or non-votable.[64]

![]() The

Standing Committee on Citizenship and Immigration, among other matters, monitors

the implementation of the principles of the federal multiculturalism policy

throughout the Government of Canada.[65]

The

Standing Committee on Citizenship and Immigration, among other matters, monitors

the implementation of the principles of the federal multiculturalism policy

throughout the Government of Canada.[65]

![]() The

Standing Committee on Government Operations and Estimates has a very

broad mandate[66]

that includes, among other matters, the review of the effectiveness, management

and operation, together with the operational and expenditures plans of the

central departments and agencies; the review of estimates for programs delivered

by more than one department or agency; the review of the effectiveness,

management and operation of activities related to the use of new and emerging

information and communication technologies by the government; and the review of

the process for consideration of estimates and supply by parliamentary

committees.

The

Standing Committee on Government Operations and Estimates has a very

broad mandate[66]

that includes, among other matters, the review of the effectiveness, management

and operation, together with the operational and expenditures plans of the

central departments and agencies; the review of estimates for programs delivered

by more than one department or agency; the review of the effectiveness,

management and operation of activities related to the use of new and emerging

information and communication technologies by the government; and the review of

the process for consideration of estimates and supply by parliamentary

committees.

![]() The

Standing Committee on Human Resources, Skills and Social Development and the

Status of Persons with Disabilities is responsible for, among other matters,

proposing, promoting, monitoring and assessing initiatives aimed at the social

integration and equality of disabled persons.[67]

The

Standing Committee on Human Resources, Skills and Social Development and the

Status of Persons with Disabilities is responsible for, among other matters,

proposing, promoting, monitoring and assessing initiatives aimed at the social

integration and equality of disabled persons.[67]

![]() The

Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights is responsible for, among

other matters, the review of reports of the Canadian Human Rights Commission.[68]

The

Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights is responsible for, among

other matters, the review of reports of the Canadian Human Rights Commission.[68]

![]() The

Standing Committee on Official Languages deals with, among other matters,

official languages policies and programs, including reports of the Commissioner

of Official Languages.[69]

The Committee’s mandate is derived from a legislative provision requiring that

a committee of either House or both Houses be specifically charged with review

of the administration of the Official Languages Act and the

implementation of certain reports presented pursuant to this statute.[70]

The

Standing Committee on Official Languages deals with, among other matters,

official languages policies and programs, including reports of the Commissioner

of Official Languages.[69]

The Committee’s mandate is derived from a legislative provision requiring that

a committee of either House or both Houses be specifically charged with review

of the administration of the Official Languages Act and the

implementation of certain reports presented pursuant to this statute.[70]

![]() The

Standing Committee on Public Accounts deals with, among other matters, the

review of the Public Accounts of Canada and all reports of the Auditor General

of Canada.[71]

The

Standing Committee on Public Accounts deals with, among other matters, the

review of the Public Accounts of Canada and all reports of the Auditor General

of Canada.[71]

![]() The

Standing Committee on Access to Information, Privacy and Ethics reviews,

among other matters, the effectiveness, management and operation together with

the operational and expenditure plans relating to three Officers of Parliament:

the Information Commissioner, the Privacy Commissioner and the Conflict of

Interest and Ethics Commissioner. It also reviews their reports, although in

the case of the Conflict of Interest and Ethics Commissioner, the reports

concerned relate to his or her responsibilities under the Parliament of

Canada Act regarding public office holders and reports tabled pursuant to

the Lobbyists Registration Act. In cooperation with other standing

committees, the Committee also reviews any bill, federal regulation or Standing

Order which impacts upon its main areas of responsibility: access to

information, privacy and the ethical standards of public office holders. It may

also propose initiatives in these areas and promote, monitor and assess such

initiatives.[72]

The

Standing Committee on Access to Information, Privacy and Ethics reviews,

among other matters, the effectiveness, management and operation together with

the operational and expenditure plans relating to three Officers of Parliament:

the Information Commissioner, the Privacy Commissioner and the Conflict of

Interest and Ethics Commissioner. It also reviews their reports, although in

the case of the Conflict of Interest and Ethics Commissioner, the reports

concerned relate to his or her responsibilities under the Parliament of

Canada Act regarding public office holders and reports tabled pursuant to

the Lobbyists Registration Act. In cooperation with other standing

committees, the Committee also reviews any bill, federal regulation or Standing

Order which impacts upon its main areas of responsibility: access to

information, privacy and the ethical standards of public office holders. It may

also propose initiatives in these areas and promote, monitor and assess such

initiatives.[72]

![]() The

Standing Committee on Finance is empowered to review proposals relating

to the government’s budgetary policy.[73]

The

Standing Committee on Finance is empowered to review proposals relating

to the government’s budgetary policy.[73]

Standing Joint

Committees

Standing Joint

Committees

In addition to the standing committees, there are two standing joint committees: one on the Library of Parliament and one on the Scrutiny of Regulations.[74] These are described as “joint” because their membership consists of Members of the House of Commons and Senators. In contrast to standing committees, moreover, the number of members can vary.[75] Struck for each session of Parliament, their status is formalized by statute and confirmed by the Standing Orders of the House of Commons and the Rules of the Senate.[76]

The Standing Joint Committee on the Library of Parliament is charged with the review of the effectiveness, management and operation of the Library of Parliament, which serves both the House of Commons and the Senate.[77] The mandate of this Committee arises from a statutory provision giving direction and control of the Library to the Speakers of the Senate and the House, with the provision that they are to be assisted by a joint committee.[78] At the beginning of each session, the Committee usually seeks confirmation of its mandate by presenting a report for that purpose to each House, which is usually concurred in.[79]

The Standing Joint Committee on Scrutiny of Regulations[80] is mandated to review and scrutinize statutory instruments.[81] The Committee’s mandate is set out in part in the Standing Orders[82] and in part in the Statute Revision Act and the Statutory Instruments Act.[83] At the beginning of each session, the Committee presents a report relating to its review of the regulatory process, proposing a more detailed mandate. When the report is concurred in by the House of Commons and Senate, this proposed mandate then becomes an order of reference to the Committee for the remainder of the session.[84]

Legislative

Committees

Legislative

Committees

Legislative committees are created on an ad hoc basis by the House solely to draft or review proposed legislation.[85] They therefore do not return from one session to the next, as standing and standing joint committees do. They are established as needed when the House adopts a motion making a referral,[86] and cease to exist upon presentation of their report on the draft legislation to the House. They consist of a maximum of 15 Members drawn from all recognized political parties, plus the Chair.[87]

Their mandate is restricted to examining and inquiring into the bill referred to them by the House, and presenting a report on it with or without amendments.[88] They are not empowered to consider matters outside the provisions of the bill,[89] nor can they submit comments or recommendations in a substantive report to the House.[90] However, if the House has instructed a committee to prepare a bill, it is empowered under the Standing Orders to recommend in its report the principles, scope and general provisions of the bill and may include recommendations regarding legislative wording.[91]

Special

Committees

Special

Committees

As in the case of legislative committees, special committees are ad hoc bodies created as needed by the House. Unlike legislative committees, however, they are not usually charged with the study of a bill,[92] but rather with inquiring into a matter to which the House attaches particular importance.[93] Every special committee is established by an order of reference of the House. The motion usually defines its mandate and may include other provisions covering its powers, membership—the number of members varies—and the deadline for presentation of its final report to the House.[94] The content of the motion varies with the specific task entrusted to the committee. Special committees cease to exist upon presentation of their final report.[95]

Special Joint

Committees

Special Joint

Committees

Special joint committees are created for the same purposes as special committees: to study matters of great importance. However, they are composed of Members of the House of Commons and Senators. They are established by order of reference from the House, and another from the Senate.

The House that wishes to initiate a special joint committee first adopts a motion to establish it and includes a provision inviting the other Chamber to participate in the proposed committee’s work.[96] The motion also includes any instruction to the committee, and sets out the powers delegated to it. It may also designate the members of the committee,[97] or specify how they are to be selected.

Decisions of one House concerning the membership, mandate and powers of a proposed joint committee are communicated to the other House by message. Both Houses must be in agreement about the mandate and powers of the committee in order for it to be able to undertake its work. Once a request to participate in a joint committee is received, the other House, if it so desires, adopts a motion to establish such a committee and includes a provision to be returned to the originating House, stating that it agrees to the request. Once the originating House has been informed of the agreement of the other Chamber, the committee can be organized. A special joint committee ceases to exist when it has presented its final report to both Houses.

The mandate of a special joint committee is set out in the order of reference by which it is established. In the past, special joint committees have been set up to inquire into such matters as child custody,[98] defence,[99] foreign policy,[100] a code of conduct for Members and Senators[101] and Senate reform.[102] Constitutional issues have often been referred to special joint committees.[103] From time to time, they have also been charged with review of legislation, either by being empowered to prepare a bill[104] or by the referral of a bill to the committee after second reading.[105]

Subcommittees

Subcommittees

Subcommittees are working groups that report to existing committees. They are normally created by an order of reference adopted by the committee in question.[106] They may also be created directly by the House, but this is less common.[107] The establishment of subcommittees may also be provided for in the Standing Orders.[108]

The establishment of subcommittees is usually designed to relieve parliamentary committees of planning and administrative tasks, or to address important issues relating to their mandate.[109] A subcommittee is able to devote all the necessary attention to the mandate it is given, whereas the committee it reports to is likely to be dealing with a heavy agenda and conflicting priorities. Subcommittees generally have a lower level of activity than the committees they report to, but in some cases they may be just as busy. Apart from the cases in which they are created by the House or required pursuant to the Standing Orders, a parliamentary committee is under no obligation to strike subcommittees, the decision rests entirely with its members.[110]

Unless provision has already been made in the Standing Orders, it is up to the committee—or the House, as the case may be—that creates a subcommittee to establish its mandate in an order of reference, specifying its membership (the number of members varies), powers and any other conditions that are to govern its deliberations.[111] Depending on the circumstances and the type of mandate it is assigned, a subcommittee will exist as long as the main committee does, or will cease to exist when its task is completed.

Not every type of committee can create subcommittees. Under the Standing Orders, standing committees (including, where the House is concerned, standing joint committees) may do so.[112] In practice, most of them create a subcommittee on agenda and procedure, commonly referred to as a “steering committee”, to help them plan their work.[113] A steering committee is the only type of subcommittee a legislative committee is empowered to create under the Standing Orders.[114] Special committees may create subcommittees only if empowered to do so by the House (and by the Senate, in the case of a special joint committee).[115]

Once established, subcommittees carry out their own work within the mandate entrusted to them. They are free to adopt rules to govern their activities, provided these are consistent with the framework established by the main committee.[116] Subcommittees report to their main committee with respect to resolutions, motions or reports they wish the main committee to concur in.[117] Proposals by a steering committee as to how the main committee’s work is to be organized must be approved by the committee itself. In every case, this is achieved by having the subcommittee adopt a report for presentation to the main committee.[118] Unless the House or the committees decide otherwise, main committees may amend the reports of their subcommittees before concurring in them.[119]

[54] There is also a unique body, the Liaison Committee, responsible for apportioning funds authorized by the Board of Internal Economy to meet the expenses of committee activities. For further information, see “Funding of Activities” under the section in this chapter entitled “Committee Proceedings”.

[55] Standing Order 104(2).

[56] For example, the House has a Standing Committee on Transport, Infrastructure and Communities, although no government department has such a name.

[57] The Committee on Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development is an example of the first category; the Committee on Procedure and House Affairs is an example of the second; and the Committee on Government Operations and Estimates is an example of the third.

[58] Standing Order 108(2). It specifically excludes the two standing joint committees, the Standing Committee on Procedure and House Affairs, the Standing Committee on Access to Information, Privacy and Ethics and the Standing Committee on Official Languages. Specific mandates are nevertheless provided for each of these committees (for further information, see the next section entitled “Specific Mandates”). For all other standing committees, any specific mandate is in addition to their general mandate.

[59] For further information, see the section in this chapter entitled “Studies Conducted by Committees”.

[60] Therefore, it is not unusual for the House to refer matters of privilege to the Committee for further study, if the Speaker has found prima facie grounds. For further information, see Chapter 3, “Privileges and Immunities”.

[61] Standing Order 108(3)(a).

[62] Standing Orders 104(1), 107(5) and 114(1). For further information, see the section in this chapter entitled “Committee Membership, Leadership and Staff”.

[63] Standing Order 115(4).

[64] Standing Orders 91.1 and 92. For further information, see Chapter 21, “Private Members’ Business”.

[65] Standing Order 108(3)(b).

[66] Standing Order 108(3)(c). Some 10 specific mandates are assigned to this committee alone.

[67] Standing Order 108(3)(d).

[68] Standing Order 108(3)(e).

[69] Standing Order 108(3)(f).

[70] R.S 1985, c. 31 (4th Supp.), s. 88.

[71] Standing Order 108(3)(g).

[72] Standing Order 108(3)(h).

[73] Standing Order 83.1. This provision, added to the Standing Orders in 1994 (Journals, February 7, 1994, pp. 112‑20, in particular pp. 117, 119‑20), extends the Committee’s mandate to include, in the words used by the Government House Leader in proposing the new standing order, “an annual public consultation on what should be in the next budget” (Debates, February 7, 1994, p. 962).

[74] Standing Order 104(3). Since 1867, there have been three other standing joint committees: on Printing, on the Parliamentary Restaurant and on Official Languages. Reference to the first two is still found in Senate Rule 86(1). Reference to the Standing Joint Committee on Printing was dropped from the Standing Orders in 1986 (Journals, February 6, 1986, pp. 1644‑66, in particular p. 1657; February 13, 1986, p. 1710). While the Standing Orders have never contained a reference to the Standing Joint Committee on the Parliamentary Restaurant, the House began to name members to it in 1909 (Journals, February 10, 1909, p. 69). The last occasion on which members were named to this Committee was during the First Session of the Thirty‑Second Parliament (Journals, May 14, 1980, pp. 168‑70). The Standing Joint Committee on Official Languages ceased to exist at the beginning of the Second Session of the Thirty-Seventh Parliament, when the Senate sent a message announcing that it would no longer be participating in the Committee, and the House accordingly established its own Standing Committee on Official Languages (Journals, October 10, 2002, p. 59; November 7, 2002, pp. 181-2).

[75] For further information, see the section in this chapter entitled “Committee Membership, Leadership and Staff”.

[76] Standing Order 104(3) and Senate Rule 86(1)(a) and (d).

[77] Standing Order 108(4)(a).

[78] Parliament of Canada Act, R.S. 1985, c. P‑1, s. 74(1).

[79] See, for example, the First Report of the Standing Joint Committee on the Library of Parliament, presented to the House on June 14, 2006 (Journals, p. 277) and concurred in on June 19, 2006 (Journals, p. 296).

[80] For further information on the nature and role of the Standing Joint Committee on Scrutiny of Regulations, see Chapter 17, “Delegated Legislation”.

[81] A statutory instrument is a rule, order, regulation or other regulatory text as defined in s. 2(1) of the Statutory Instruments Act, R.S. 1985, c. S‑22.

[82] Standing Order 108(4)(b).

[83] R.S. 1985, c. S‑20, s. 19(3) and c. S‑22, s. 19.

[84] See, for example, Journals, November 21, 2007, pp. 186-7.

[85] They were established in 1985 by amendments to the Standing Orders giving effect to recommendations of the Lefebvre and McGrath committees. It was felt at the time that standing committees, because of their newly broadened powers to undertake inquiries on their own initiative, could not readily take on the review of bills. The proposed solution was the establishment of legislative committees appointed solely to study draft legislation (Journals, June 27, 1985, pp. 910‑9, in particular pp. 915‑6. See also the Sixth Report of the Special Committee on Standing Orders and Procedure, Minutes of Proceedings and Evidence, April 28, 1983, Issue No. 19, pp. 3‑11; First Report of the Special Committee on the Reform of the House of Commons, Minutes of Proceedings and Evidence, December 19, 1984, Issue No. 2, pp. 3‑23, in particular pp. 7‑10). An amendment to the Standing Orders dated April 11, 1991 (Journals, pp. 2904‑32, in particular pp. 2926‑9) provided for a system of eight “standing legislative committees” divided equally among four of the five sectors into which the standing committees are grouped. Bills were referred to one of the two committees in the appropriate sector, and a separate Chair was appointed to lead the review of each bill. On January 25, 1994, the House amended its Standing Orders to eliminate the sector system and re-establish that of legislative committees, to be created as needed (Journals, pp. 58‑61, in particular pp. 60‑1).

[86] See, for example, Journals, February 13, 2008, pp. 434-6. An order of reference is a motion adopted by the House charging a committee with the review of a specific matter, or defining the scope of its deliberations. For further information, see the section in this chapter entitled “Studies Conducted by Committees”. Committees also adopt orders of reference for their subcommittees.

[87] For further information, see the section in this chapter entitled “Committee Membership, Leadership and Staff”.

[88] Standing Order 113(5).

[89] In 2006, the Chair of a legislative committee had ruled a motion inadmissible because it exceeded the committee’s mandate, which at the time was to review Bill C-2, An Act providing for Conflict of Interest Rules, Restrictions on Election Financing and Measures Respecting Administrative Transparency, Oversight and Accountability. The motion in question called upon the government to proclaim forthwith the coming into force of legislation passed by a previous Parliament (Legislative Committee on Bill C-2, Minutes of Proceedings, May 9, 2006, Meeting No. 4).

[90] For further information on what constitutes a substantive report, see “To Report to the House from Time to Time” under the section in this chapter entitled “Committee Powers”.

[91] Standing Order 68(5).

[92] Bills have been referred from time to time to special committees. See, for example, the case of the Special Committee on the Non-Medical Use of Drugs in the Second Session of the Thirty-Seventh Parliament. Although the Committee had already presented its final report (Journals, December 12, 2002, p. 302), the House subsequently reactivated it to study Bill C‑38, An Act to amend the Contraventions Act and the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act (Journals, October 21, 2003, pp. 1140-1).

[93] See, for example, Journals, January 25, 1977, pp. 286‑7; March 30, 1993, pp. 2742‑3; April 8, 2008, pp. 665-7. Between 1979 and 1985, the House employed a variant of the special committee known as a “task force”; membership was limited, replacements were not permitted and a limited time was allowed for the group to complete its work. For a detailed analysis of the task force experience in the House of Commons, see O’Brien, A., “Parliamentary task forces in the Canadian House of Commons: A new approach to committee activity”, The Parliamentarian, Vol. LXVI, No. 1, January 1985, pp. 28‑32.

[94] Standing Order 105. The order of reference may also include provisions to regulate the work of the committee. See, for example, the 2001 Order of Reference establishing the Special Committee on the Modernization and Improvement of the Procedures of the House of Commons (Journals, March 15, 2001, pp. 175-6; March 21, 2001, pp. 208-9). Under the terms of the motion, the Committee could not adopt a report for presentation to the House without the unanimous consent of its members.

[95] An amendment to the motion to approve the final report seeking to refer the report back to the committee may be proposed, without the need for a motion to reconstitute the committee. See Speaker Macnaughton’s Ruling, Journals, December 1, 1964, pp. 941‑7. However, a special committee created to examine a bill ceases to exist when it presents its report on the bill, with or without amendment. See, for example, the Second Report of the Special Committee on the Non-Medical Use of Drugs, presented to the House on November 6, 2003 (Journals, p. 1248).

[96] Typically, the motion ends with a request as follows: “That a message be sent to the Senate requesting that House to unite with this House for the above purpose”. See, for example, Journals, March 16, 1994, p. 263.

[97] Each House retains control over its own members on the committee.

[98] Journals, November 18, 1997, pp. 224‑5.

[99] Journals, February 23, 1994, pp. 186‑7.

[100] Journals, March 16, 1994, pp. 262‑5.

[101] Journals, March 12, 1996, pp. 83‑4.

[102] Journals, December 22, 1982, pp. 5493‑4.

[103] Journals, October 23, 1980, pp. 601‑3; June 16, 1987, pp. 1100‑2; December 17, 1990, pp. 2488‑90; May 17, 1991, p. 43; June 19, 1991, pp. 226‑7; October 1, 1997, pp. 59‑61; October 28, 1997, pp. 158‑61.

[104] See, for example, Journals, November 22, 1991, pp. 717‑8.

[105] See, for example, Journals, March 20, 1993, pp. 2742‑3.

[106] See, for example, Standing Committee on Public Safety and National Security, Minutes of Proceedings, May 29, 2006, Meeting No. 4.

[107] See, for example, Journals, May 28, 1984, pp. 665-6; October 9, 1986, p. 66; November 2, 2004, pp. 182-3.

[108] For example, under the Standing Orders, the Standing Committee on Procedure and House Affairs is required to constitute the Subcommittee on Private Members’ Business, to determine whether any of the items placed in the order of precedence are non-votable according to certain criteria. See Standing Order 91.1; Standing Committee on Procedure and House Affairs, Minutes of Proceedings, April 6, 2006, Meeting No. 1.

[109] In the discharge of their mandate, some committees have chosen an arrangement other than subcommittees. These committees are divided into “groups”, each of which is assigned a portion of the committee’s mandate. For example, the Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs and International Trade split into two groups to receive foreign delegations one by one (Minutes of Proceedings, Meeting No. 1, October 8, 1997); the Committee on Official Languages wanted to divide into two groups to travel across Canada (Minutes of Proceedings, February 8, 2005, Meeting No. 15).

[110] For example, during the Second Session of the Thirty-Ninth Parliament, the standing committees on Natural Resources, Canadian Heritage and the Status of Women had no subcommittees.

[111] See, for example, Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs and International Development, Minutes of Proceedings, May 10, 2006, Meeting No. 2.

[112] Standing Order 108(1)(a).

[113] For further information on steering committees, see “Organization and Conduct of Business” under the section in this chapter entitled “Committee Proceedings”.

[114] Standing Order 113(6).

[115] See, for example, Journals, March 21, 2001, pp. 208-9.

[116] See, for example, Subcommittee on Bill C-28 of the Standing Committee on Finance, Minutes of Proceedings, December 4, 2007, Meeting No. 1.

[117] See, for example, Subcommittee on International Human Rights of the Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs and International Development, Minutes of Proceedings, June 5, 2007, Meeting No. 21. Subcommittees are not empowered to present reports to the House. For further information, see the section in this chapter entitled “Committee Powers”.

[118] See, for example, Legislative Committee on Bill C-30, Minutes of Proceedings, February 6, 2007, Meeting No. 4. Under Standing Order 113(6), legislative committees retain the power to approve arrangements made by their steering committees.

[119] See, for example, Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs and International Trade, Minutes of Proceedings, June 6, 2002, Meeting No. 88. There is one exception to this rule: under Standing Order 91.1(2), the Standing Committee on Procedure and House Affairs is deemed to have adopted the reports of its Subcommittee on Private Members’ Business recommending that the items listed therein, which it has determined should not be designated non-votable, be considered by the House.