FOPO Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

Traceability and Labelling of Fish and Seafood Products

Fish and seafood products are important sources of protein for Canadian consumers, with Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) data noting an availability of about 9 kilograms per person in 2020, an increase over 15% since 2010. It is imperative that Canadians can rely on a transparent supply chain and make informed choices regarding food safety, environmental sustainability and labour rights when it comes to purchasing their fish and seafood products. It is also important that Canadian fish harvesters not be disadvantaged due to differential traceability and labelling requirements for imported products on Canadian supermarket shelves.

To that end, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Fisheries and Oceans (the committee) undertook a study on implementing a boat-to-plate traceability and labelling system to avoid the mislabelling of imported fish and seafood products. The study also examines the potential socio-economic, environmental and food safety impact of such a system.

The committee held five meetings in February and March 2022 and heard from Canadian and international researchers, four federal government departments, eco-certification organizations, fish harvester and processor organizations and retailers. The committee would like to thank all the witnesses who appeared. The committee is pleased to present the results of its study in this report, along with recommendations based on the evidence it heard.

Background

Roles and Responsibilities of Federal Departments

A common theme heard during the committee’s study was the lack of clear lines of responsibility and accountability in Canada’s fish and seafood traceability and labelling policies. Witnesses identified gaps in Canada’s traceability and labelling requirements leading to confusion and possible fraud at the consumer level as there is no agency responsible for leading on the issues of ensuring the accuracy of fish and seafood product labelling. Therefore, the committee feels that it is helpful to provide a brief synopsis of each department’s responsibilities.

Fisheries and Oceans Canada

According to Adam Burns, Director General, Fisheries and Resources Management, DFO, demand for traceability and labelling of fish and seafood products has been

largely driven by various market access requirements, many in the form of barriers to trade resulting from requirements of other countries. Other incentives that have led to developments in this area are purely consumer- and market-driven, such as eco-labelling.[1]

He indicated that DFO’s catch certification program was created in 2010 to position the Canadian industry to respond to international market access requirements such as the European Union’s Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated (IUU)[2] regulations. Adam Burns added that DFO does not regulate the importation of fish and seafood products into Canada. DFO stressed that industry participation in the catch certification program is market driven. The program certifies only export fisheries products, based on foreign requirements. Therefore, Canadian companies choose to participate in the process based on their targeted export markets. For imported products that are subsequently re‑exported, Canadian importers must receive certification from the country of origin for the product.

When it comes to Canadian fish and seafood processed offshore and being reimported, the committee heard from Christina Callegari, Sustainable Seafood Coordinator, SeaChoice who indicated that traceability information can be lost along the way. She stated:

Seafood is unique in that we have transshipments, so multiple products coming from different boats may get put on one boat for processing and then sent to another place. That's certainly a challenge the seafood industry faces, in particular in terms of maintaining that traceability once it gets to the port.[3]

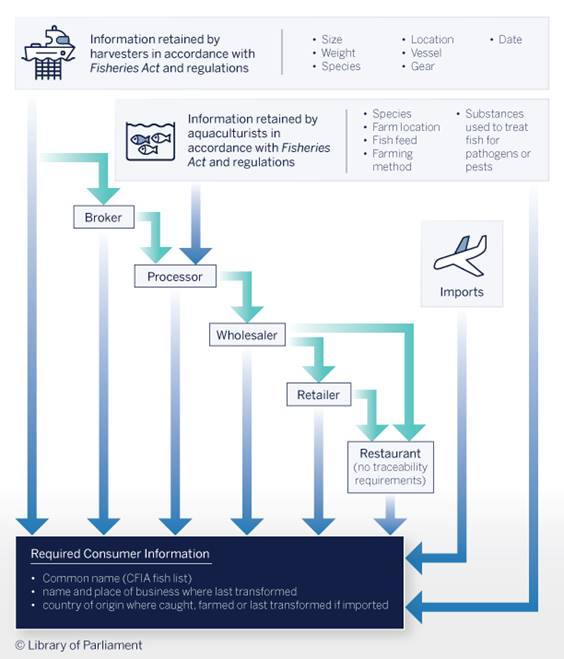

The information requirements for both imported and Canadian-caught fish and seafood are indicated in Figure 1.

Figure 1—Farmed and Wild-Caught Fish and Seafood Product Traceability in the Canadian Supply Chain

Source: Fishery (General) Regulations (SOR/93-53), section 22; Safe Food for Canadians Regulations (SOR/2018‑108), sections 90, 91 and 92; Aquaculture Activities Regulations (SOR/2015-177); Pacific Aquaculture Regulations (SOR/2010-270); and SeaChoice, Losing Information Along Canadian Seafood Supply Chains.

Canadian Food Inspection Agency

The committee was informed by Tammy Switucha, Executive Director, Food Safety and Consumer Protection Directorate that traceability and labelling requirements under the Safe Food for Canadians Regulations (SFCR) focus on food safety in Canada and apply to fish and seafood processors that import, export or trade within Canada.[4] In her view, SFCR requirements are “consistent with standards set by the international food standard-setting body, Codex Alimentarius.”

Tammy Switucha indicated that there are two main components to traceability: document and labelling requirements. The SFCR require businesses that “import, export or trade within Canada to keep records that allow food to be traced–one step back and one step forward–to the point of retail.” Regarding labelling, fish and seafood products must have a label with information such as the common name which corresponds to the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) Fish List,[5] name and place of business, and lot code or unique identifier. The scientific name of the fish, location of the catch or type of fishing gear used are not mandatory labelling information as the issues of sustainable fishing do not fall within CFIA’s mandate. With respect to country-of-origin labelling, CFIA requires that a product be labelled as “coming from the country in which the food has undergone the last substantial processing step that has changed the nature of the food.”[6]

Canada Border Services Agency

The Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) is responsible for enforcing regulations, including those developed by CFIA and in the Customs Act, at the border. According to Shawn Hoag, Director General, Commercial Program, CBSA:

In terms of fish and seafood importation, the CBSA plays a role in delivering the program by verifying that other government department requirements are met for seafood being imported and exported to and from Canada, as well as administering the Customs Act. […] These activities primarily include verifying that any required licences, permits, certificates or other documentation required to import the goods to Canada are provided while also ensuring that appropriate duties and taxes are remitted by the importers.[7]

Global Affairs Canada

According to Doug Forsyth, Director General, Market Access, Global Affairs Canada (GAC) plays a limited role in the fish and seafood traceability and labelling policy. He noted that the core role of GAC on this file is:

that foreign and domestic producers be treated the same way, subject to the same rules and the same conditions of competition. This means that any new measures and compliance procedures Canada could develop with respect to fish and seafood products and apply to imported products will also need to apply similarly to Canadian products.[8]

Consultation on Boat-to-Plate Traceability for Fish and Seafood Products

In the mandate letter issued to then-Minister Bernadette Jordan on 13 December 2019, the Prime Minister directed the minister to: “[s]upport the Minister of Health who is the Minister responsible for the Canadian Food Inspection Agency in developing a boat-to-plate traceability program to help Canadian fishers to better market their high-quality products.”[9] The committee is concerned that the boat-to-plate traceability program was no longer mentioned in the mandate letter issued to Minister Joyce Murray on 16 December 2021.[10]

On 13 August 2021, CFIA, along with Agriculture and Agri-food Canada and DFO, launched a consultation on a discussion paper to inform the development of proposals to enhance boat-to-plate traceability and labelling of fish and seafood in Canada.[11] According to CFIA, that discussion paper was drafted after an engagement with various participants in the fish and seafood sector. The consultation, concluded on 11 December 2021, sought feedback from a broader range of stakeholders, including consumers.

Three key themes were explored in the CFIA discussion paper:

- Consumer protection and food safety (as it relates to fish and seafood);

- Sustainability and fisheries management related to traceability and combatting [IUU] fishing; and

- Market access, trade, and marketing of Canadian fish and seafood.[12]

According to a 2 November 2021 press release from Oceana Canada, however,

the government has failed to outline a timeline, next steps or a strategy to protect Canadian fishers, seafood businesses, consumers and our oceans from the economic and environmental losses associated with mislabelled and illegally-caught products.[13]

Therefore, the committee would like to take this opportunity to urge the government to rapidly implement a traceability and labelling program, one that would protect consumers, promote the health of our fishing industry, safeguard international obligations, and build a blue economy.

Consumer Decision-Making and Protections

The committee heard that the gaps in Canada’s labelling requirements for fish and seafood is leading to confusion and possible fraud at the consumer level. Referring to the CFIA Fish List, Christina Callegari stated:

In 2019, SeaChoice conducted an extensive review of the CFIA fish list. This is a list that provides guidance for the accepted common names for seafood sold in Canada. We found numerous examples of generic common names, such as shrimp, used for 41 different species. We also found, for example, that red snapper was used to identify a species of rock fish, an entirely different type of fish.[14]

While Tammy Switucha stated that CFIA works “very closely with all levels to ensure that consumers are protected from end to end in the supply chain,”[15] Sayara Thurston of Oceana Canada countered that:

our current country-of-origin requirements just require that a product be labelled with the last place of transformation. You could be buying something that says ‘Product of Canada’ or ‘Product of the United States’, but that doesn't necessarily reflect where that product was originally fished. This makes it really hard for consumers to get an accurate sense of what they're buying if they're trying to avoid certain countries or certain practices because they have concerns about those things or if they're trying to buy locally. Right now, they don't have the accurate information to make those choices.[16]

Christina Callegari testified that “Canada also lacks robust import requirements, leaving us at risk of importing products associated with IUU fishing, or mislabelled seafood. This especially puts Canadian businesses, such as major retailers, at risk by allowing illegal or critically endangered species to go unnoticed and sold to consumers.” She concluded that “Canadians deserve to know more about their seafood, but Canada's seafood labels do not allow consumers to make an informed choice to buy sustainably or support domestic producers.”[17]

Kurtis Hayne, Program Director, Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) testified that:

MSC seafood is accurately labelled, enabling consumers to make an informed choice and protecting them from seafood fraud. DNA testing has shown that our species mislabelling for MSC seafood is less than 1%, much lower than studies that the committee's heard about for other seafood products and other global estimates of mislabelling rates.[18]

Kurtis Hayne also stated his organization’s research has shown “that Canadians want to know that their seafood is traceable—65% consumers want to know the fish they buy can be traced to a known and trusted source.”[19]

Robert Hanner, Professor, University of Guelph lamented that “if we can't even get the name right, it's not clear that we should assume that this food is safe.”[20]

Professor Hanner continued noting that:

Here in Canada I am really despondent given the fact that our industry is already complying with the European Union regulations to be able to export our seafood to that market, and yet we, as Canadians, don't enjoy that same level of transparency. We are eating trash fish from international markets being dumped into Canada without this level of transparency, while our own industry is already complying with it if they are exporting to the European Union.[21]

As part of its study, the committee heard from witnesses, including those from European Union countries such as Carmen G. Sotelo, Researcher, Spanish National Research Council who stated that, after the European Union implemented robust labelling requirements, “we have observed that seafood fraud at retailers both in Spain and Europe has been decreasing over time since the 1990s,” with only a modest increase in cost to the consumer.[22]

Among other requirements, the European labelling laws require the scientific name of the species, geographic catch area and gear used.[23] The committee also notes that Canadian fish and seafood exporters are already required to follow European traceability and labelling regulations, which should be explored as requirements for the Canadian domestic market as well.

Robert Hanner reiterated that “Canada's labelling legislation should be aligned with that of the European Union in mandating scientific names on seafood products along with additional criteria concerning geographic origin, processing history, and production and harvest methods to promote consumer choice and effective boat-to-plate traceability. This legislation should be enforced.”[24]

Recommendation 1

That the Government of Canada implement a Canadian seafood traceability and labelling system that supports the ability of Canadians to make informed decisions when purchasing seafood, including considerations that could affect their health and the optimization and sustainability of the resource.

Recommendation 2

That the Government of Canada implement a Canadian traceability and labelling system that will be interoperable with the European Union’s system and standards to ensure full-chain traceability for fish and seafood products. This system should be mandatory, rules-based and applicable to all species, whether for import or export.

Recommendation 3

That the Government of Canada introduce regulations requiring full-chain traceability and improved labelling standards for fish and seafood products. The required labelling information should be readily accessible electronically by regulatory bodies and include:

- The species’ scientific name, regardless of whether it is wild-caught or farmed;

- The catch or farm country of origin and, if applicable, processing location; and

- The product’s harvesting or farming method.

Further, the Government of Canada should introduce support to enable the Canadian industry to innovate and adopt new technology in response to enhanced traceability and labelling requirements.

Recommendation 4

That the Department of Fisheries and Oceans work with the Canadian Food Inspection Agency to review the Agency’s “Fish List”. This review should aim to provide a consistent basis for determining common names for fish and seafood. The Canadian Food Inspection Agency should also improve its DNA testing to validate the labelling of imported and domestic products, and invest in a range of inspection, audit and enforcement mechanisms to deter fraud.

Recommendation 5

That, once the Canadian traceability and labelling system for fish and seafood products has been implemented, the Department of Fisheries and Oceans work in collaboration with other government departments and jurisdictions to develop a public service campaign to increase consumer awareness about the full boat-to-plate traceability of high-quality Canadian-caught products made possible by the new system.

Implementation of a Boat-to-Plate Traceability and Labelling Program

The committee looks forward to the implementation of a boat-to-plate traceability and labelling program as set out in the Prime Minister’s mandate letter to the Minister of Fisheries, Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard. Tammy Switucha was unable, however, to provide a clear indication of a timeline.[25]

Sayara Thurston, Campaigner, Oceana Canada recommended that the Government of Canada commit “to an ambitious timeline for developing full-chain traceability. To facilitate this, we recommend that a multi-department task force be convened to allow all relevant departments to work together.” She pointed to the model of the United States where a task force on traceability was formed in 2014, and legislation was adopted two years later.[26]

It should be noted that Canadian fish and seafood harvesters and processors are advocates of greater traceability and transparency. Claire Canet, Project Officer, Regroupement des pêcheurs professionnels du sud de la Gaspésie, raised the example of Gaspé lobster sales during the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020:

Because our lobster was identifiable, we were able to get the support of the distributors, such as Metro, who were able to put forward in their retail shops identifiable Quebec products. That allowed our buyers to maintain the price that they were selling to Metro and some more minor chains. Ultimately, the Gaspé lobster fishermen were able to maintain their selling price to the main buyer.[27]

The possible additional costs of implementing a traceability and labelling system do not seem to be a concern. Laura Boivin, Chief Executive Officer, Fumoir Grizzly Inc., noted that the cost of eco‑certification through the Aquaculture Stewardship Council only added 0.05% in extra overhead coast.[28]

Ian MacPherson, Senior Advisor, Prince Edward Island Fishermen’s Association also identified electronic logs to capture catch information through an app as a piece of the traceability and labelling system. He explained that his association:

invested extensive time and resources into this app so that harvesters can access a unit that not only meets the Department of Fisheries and Oceans parameters for function, but is user friendly and offered at a reasonable cost to the fishers. It is critical that fishers be involved in the process of knowing where their catch data goes, who has access to the data and where the data is stored.[29]

Scott Zimmerman, Chief Executive Officer, Safe Quality Seafoods Associates, emphasized however, that:

At the end of the day, it's a matter of the competency of the people who are conducting those traceability audits of those systems. There's a very limited number of boots on the ground that can conduct that type of reconciliation, so they have to push their resources in one direction.[30]

At the retailer level, while the committee heard about the case of Costco selling out-of-season lobster in 2017 and promoting them as Magdalen Islands lobster,[31] the “complete” traceability of fish and seafood products at Metro is “part of a comprehensive approach to corporate responsibility that dates back to 2010, when the company adopted its policy on sustainable fisheries and aquaculture.”[32] According to Alexandra Leclerc, Manager, Procurement, Metro Inc., comprehensive traceability information appears on the label of 90% to 95% of Metro’s products. However, in the opinion of Sylvain Charlebois, Professor, Dalhousie University greater public awareness is needed about eco-certification labels and traceability information provided on these labels:

At the seafood counter of a grocery store, where products featured certification by MSC and the Ocean Wise Seafood program, I asked the employee behind the counter what that meant. He didn't know. There is seemingly a lack of information. I was the first customer in four years to ask that question. The certification programs are not explained to the general public.[33]

Recommendation 6

That the Government of Canada define and commit to a timeline and target date for implementing a Canadian seafood traceability and labelling system.

Recommendation 7

That the Government of Canada establish an interdepartmental task force led by Fisheries and Oceans Canada, and involving key agencies, supply chain participants and other stakeholders to develop a coordinated response to fish and seafood product mislabelling and to implement full boat-to-plate traceability for all fish and seafood products harvested, farmed or sold in Canada. This task force should also consider the creation of an oversight entity to enforce the effective implementation of the Canadian traceability and labelling system and to measure progress outcomes.

Recommendation 8

That the Government of Canada develop labelling regulations to ensure full boat-to-plate traceability of imported and domestic fish and seafood products. These regulations should require that key information be paired with products along the entire supply chain using electronic records from point of catch to point of sale.

Protection of the Supply Chain from Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fisheries Practices

While the committee will undertake a larger and more in-depth study of IUU fishing, it would like to draw attention to fraud and human rights abuses happening when fish and seafood products are not properly regulated and traced. Sayara Thurston stated

seafood fraud or mislabelling includes swapping a cheaper or more readily available one for one that is more expensive, substituting farmed products for wild-caught ones, or passing off illegally caught fish as legitimate. These practices undermine food safety, cheat consumers and the Canadian fishing industry, weaken the sustainability of fish populations, and mask global illegal fishing and human rights abuses.[34]

It is imperative that a new traceability and labelling system be able to guard against IUU fisheries. Sayara Thurston raised a worthwhile example from the European Union system:

For example, in the European Union system, if countries are suspected of not having proper fisheries management and not keeping illegal products out of their supply chain, they will give them a yellow card or a red card, kind of like in sport. One of their current red-carded countries is Cameroon, and Canada imported fish from Cameroon last year, but that's not necessarily something the consumer will have access to in terms of information.[35]

Recommendation 9

That the Government of Canada implement a seafood traceability and labelling system that protects Canadian supply chains from seafood of illegal, unreported, unregulated (IUU) harvest and harvest utilizing exploited workers.

Promotion of Canadian Seafood Productions and Protection of Their Market Value

The Canadian fish and seafood sector are important drivers of the economy, and deliver high-quality products. According to CFIA, 92% of retail labels are correct, with only 4% of domestically processed fish and seafood products being incorrectly labelled per the current traceability standards.[36] Much of the misrepresented product is sold in restaurants where Oceana Canada found that 47% of the samples taken from Canadian restaurants of certain species were incorrectly labelled.[37] Finding discrepancies between CFIA and Oceana Canada resulted from the fact that CFIA’s investigation focused on the upstream part of the supply chain (processors and importers) while Oceana Canada examined the downstream part (retailers and restaurants). In the committee’s view, this apparent traceability information loss along the supply chain raises a red flag and deserves further investigation to identify specific problem areas within the supply chain as recommended by Paul Lansbergen, President, Fisheries Council of Canada.[38] As previously noted, Canadian harvesters and processors are strongly in favour of traceability and labelling standards, from a sustainability perspective as well as a way of maintaining an equitable share of the market with unscrupulous importers.

CFIA’s findings were corroborated by Christina Burridge, Executive Director, BC Seafood Alliance. She mentioned that the mislabelling of fish and seafood products in Canada involves essentially “illegally-harvested products entering small-scale retail and foodservice market.”[39] Christina Burridge emphasized that, on the West Coast, “each vessel is fully accountable for every single fish it catches, whether retained or released, through a monitoring program that requires a 100% electronic monitoring or at-sea observers and 100% dockside validation before the catch goes to the processing plant.” In addition, most processing plants maintain MSC chain of custody certification. In her opinion, illegal products entering the domestic market appear to originate from recreational or food, social and ceremonial fisheries.

Paul Lansbergen supported Christina Burridge’s point of view. He indicated that the extent of the mislabelling of domestic fish and seafood products in Canada is limited, and Canadian fish and seafood processors have been adhering to a high-level of traceability in their operations which include internal trace back capabilities and “critical control point inspection systems.”[40] In his opinion, “Canadians along with our global customers can feel confident eating our fish and seafood knowing that it is the product of one of the most advanced food safety systems in the world.”

Sonia Strobel, Co-Founder and Chief Executive Officer, Skipper Otto Community Supported Fishery, testified that:

Canadian consumers want to know if their seafood purchases are supporting Canadian fishing families or if they're propping up illegal operations and slavery, yet locally caught seafood is indiscernible from foreign fish in the marketplace because of our labelling rules.

From our perspective, what we see as the largest problem is imported seafood being incorrectly labelled in the marketplace, along with the difficulties for Canadian harvesters and Canadian small businesses to compete with that, and then the resulting blind eye that gets turned to that mislabelling and how that damages harvesters and consumers.[41]

Ian MacPherson agreed that a boat-to-plate traceability and labelling regime would be beneficial to his membership, explaining that:

the shore price should reflect the value in the marketplace. If the supply chain is to remain healthy then the benefits should translate right from the wharf all the way through the supply chain. Harvesters want to be paid fairly and appropriately for the catch that they've brought in, and not have substitutes.[42]

He added that

We feel the traceability of seafood is important in terms of keeping our high-calibre, international reputation intact; ensuring lower and higher-value species are not over exploited; preserving international sustainability certifications; and elevating consumer confidence in the seafood products they purchase at the retail level.[43]

Recommendation 10

That the Government of Canada implement a seafood traceability, labelling and certification system that protects the market value and market access of legally caught Canadian seafood and the prices that harvesters, processors, and retailers may receive for the seafood they sell.

Enforcement and Monitoring

Government agencies such as CFIA have recognized this issue of mislabelled fish and seafood products being sold in Canada, with Tammy Switucha stating

This is a problem. We don't dispute that. Within the authorities that we currently have, the CFIA monitors and does very specific oversight of importers of fish and seafood products. We use all the tools that we have under the law to be able to do that regulatory oversight and take enforcement, but we can't be everywhere all the time.[44]

The lack of a mandate to enforce sustainability and eco-labelling was also raised by CFIA. In the committee’s view, this issue represents an important governance gap. The committee also heard from Claire Dawson, Senior Manager, Fisheries and Seafood Initiative, Ocean Wise indicating that it is impossible to determine the environmental footprint of a given seafood without knowing where or how it is produced. In her opinion, the “opacity of the supply chain is one of the main reasons seafood is prone to fraud and mislabelling.”[45] Laura Boivin also raised the issue of a lack of transparency with respect to labelling genetically engineered seafood.[46]

Robert Hanner agreed that this is a problem explaining that

The Canadian Food Inspection Agency will do random spot-testing of declared aquaculture products—the things that are farmed and being imported into Canada—to ensure that there are not banned veterinary drug residues or other therapeutants often used by unscrupulous producers to clean up fungal infections and other potential pathogens in their farm-raised seafood. If, for example, I am an exporter in another country who has dirty fish and I mislabel it as “wild”, I get more money for it and circumvent the screening process for these kinds of banned veterinary drugs. The assumption is that it's wild, so it shouldn't have been treated in this manner.[47]

He also called for greater enforcement at different points in the supply chain as it appears to be a sort of broken telephone with mislabelling increasing as the product moves through the chain. He stated that

because we published a paper with them about their inspectors collecting seafood coming into the port of landing in Toronto, at wholesale and at retail. What we saw was that about 20% of the samples they collected and we tested at import were mislabelled; nearly 30% of the samples at wholesale and retail were mislabelled, and closer to 40% of the things at actual retail were mislabelled. […] without verification testing along the supply chain, you're really only tracing the movement of packages and not what's actually in them.[48]

Sonia Strobel concluded that

You can make all the laws you want about what should go on a label, but if we don't enforce those laws, things won't change. Because of weak enforcement, when seafood fraud is uncovered, people shrug and point to someone up the stream from them, pay the fines and carry on. It's just the cost of doing business. But there should be significant incentive for each person in the supply chain to vouch for what they're selling.[49]

One verification method suggested to the committee is DNA testing. Major grocery chain Metro uses its own traceability system that includes keeping a regularly updated database “to ensure that what [suppliers] have previously told us is still true today. Their ability to document their supply chain back to the fishing boats or farming sites used is randomly tested. We also have a DNA testing verification program to validate the species reported.”[50]

This burden should not be assumed solely by the private sector. The federal government must act in a multi-agency fashion in collaboration with stakeholders to increase its enforcement measures at all levels of the supply chain. Sylvain Charlebois recommended a “value chain approach, which was first adopted in Quebec a few years ago. This approach allows all industry players to work together and share the problems that they are facing. In my opinion, traceability affects everyone.”[51]

Canada’s International Obligations

In addition to protecting and promoting Canada’s fish and seafood harvesting and processing sector, Canada has international obligations to uphold. The 2018 Charlevoix blueprint for healthy oceans, seas and resilient coastal communities called on G7 member states to among other objectives:

Promot[e] coordinated action to address forced labour and other forms of work that violate or abuse human rights in the fishing sector that can also be related to IUU fishing … [and] support the [Food and Agriculture Association of the United Nations] Voluntary Guidelines for Catch Documentation Systems.[52]

Any traceability and labelling system will need to align with these objectives as well as general trade laws, which GAC has a responsibility to uphold. Doug Forsyth explained that GAC:

participates with and works cooperatively with other government departments on a range of issues, including the development of regulations and standards. We would be happy to continue to do that in any form necessary and under the mandate that we have to provide advice on whether the said standards and regulations are consistent with our international trade obligations.[53]

The committee welcomes this engagement as part of an interdepartmental working group to develop a boat-to-plate traceability and labelling system.

Recommendation 11

That, as the Government of Canada develops a seafood traceability and labelling system, it must ensure that international trade laws and Canada’s treaty obligations and foreign partners’ obligations to Canada are defined and factored into the system’s development.

Recommendation 12

That the Government of Canada require catch documentation to identify the origin and verify the legality of all seafood products imported nationally, in accordance with European Union requirements and Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations guidelines, which Canada agreed to support during the G7 summit in 2018. The federal government must also ensure that the new Canadian traceability and documentation systems are compatible with emerging global systems so as to avoid placing an additional regulatory burden on the industry or creating loopholes for illegally sourced products.

Collection and Protection of Harvester Data

Witnesses also raised the need to protect their own harvester data as a condition of providing it to DFO. Claire Canet said:

one of the aspects was clearly to get a connection with the systems, the computing systems, the various softwares used throughout the value chain, how it could collect those data, how they could be transmitted from one actor of the value chain to the other, knowing that at the basis was the e-log system because the traceability, it has to start from the boat, if we really want something that is solid for the end consumer, and so these data could for data protection reasons and for compatibility of systems be difficult to put into a traceability system. So one needs to look at devices that can be used right from the boat.[54]

Tammy Switucha said that CFIA is open to input from industry on the design of the boat‑to-plate traceability and labelling system, stating:

We collaborate and engage with the food industry on a regular basis, even when we're not in consultation, whether it's on a policy or on regulations. We use industry input and feedback all the time.[55]

Recommendation 13

That, as the Government of Canada develops a seafood traceability and labelling system, it must ensure the system utilizes electronic systems and software that facilitate the effective sharing of data related to fish and seafood while also ensuring sensitive information of harvesters or their businesses is secured.

Conclusion

Canadian consumers deserve to have confidence that the seafood they buy and consume is safe to eat; is harvested and processed according to standards that promote the sustainability of fish stocks, protect aquatic ecosystems, safeguard basic human rights; and is accurately labelled and marketed with integrity and transparency.

Canada’s fishing industry deserves protection from unfair, unethical and illegal competition in our domestic market and recognition in international markets of its adherence to the highest standards.

The Government of Canada has an obligation to ensure that its departments and resources are aligned and properly resourced to fulfill these expectations.

[1] Adam Burns, Director General, Fisheries and Resources Management, Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO), Evidence, 10 February 2022.

[4] Tammy Switucha, Executive Director, Food Safety and Consumer Protection Directorate, Canadian Food Inspection Agency, Evidence, 10 February 2022.

[5] Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA), CFIA Fish List.

[6] Tammy Switucha, Executive Director, Food Safety and Consumer Protection Directorate, Canadian Food Inspection Agency, Evidence, 10 February 2022.

[7] Shawn Hoag, Director General, Commercial Program, Canada Border Services Agency, Evidence, 24 March 2022.

[9] Prime Minister’s Office, ARCHIVED—Minister of Fisheries, Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard Mandate Letter, 13 December 2019.

[10] Prime Minister’s Office, Minister of Fisheries, Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard Mandate Letter, 16 December 2021.

[11] CFIA, Government of Canada launches consultation on boat-to-plate traceability for fish and seafood products, 13 August 2021.

[13] Oceana Canada, “Oceana Canada Calls on New Ministers to Move Urgently on Stalled Commitment to Transparent Seafood Supply Chains,” 2 November 2021.

[15] Tammy Switucha, Executive Director, Food Safety and Consumer Protection Directorate, Canadian Food Inspection Agency, Evidence, 10 February 2022.

[22] Carmen G. Sotelo, Researcher, Spanish National Research Council, As an Individual, Evidence, 24 March 2022.

[23] European Commission, A pocket guide to the EU’s new fish and aquaculture consumer labels, 2014.

[25] Tammy Switucha, Executive Director, Food Safety and Consumer Protection Directorate, Canadian Food Inspection Agency, Evidence, 10 February 2022.

[27] Claire Canet, Project Officer, Regroupement des pêcheurs professionnels du sud de la Gaspésie, Evidence, 1 March 2022.

[29] Ian MacPherson, Senior Advisor, Prince Edward Island Fishermen’s Association, Evidence, 1 March 2022.

[30] Scott Zimmerman, Chief Executive Officer, Safe Quality Seafoods Associates, Evidence, 3 March 2022.

[31] Claire Canet, Project Officer, Regroupement des pêcheurs professionnels du sud de la Gaspésie, Evidence, 1 March 2022.

[33] Sylvain Charlebois, Professor, Agri-Food Analytics Lab, Dalhousie University, As an Individual, Evidence, 3 March 2022.

[36] Tammy Switucha, Executive Director, Food Safety and Consumer Protection Directorate, Canadian Food Inspection Agency, Evidence, 10 February 2022.

[41] Sonia Strobel, Co-Founder and Chief Executive Officer, Skipper Otto Community Supported Fishery, Evidence, 15 February 2022.

[42] Ian MacPherson, Senior Advisor, Prince Edward Island Fishermen’s Association, Evidence, 1 March 2022.

[43] Ian MacPherson, Senior Advisor, Prince Edward Island Fishermen’s Association, Evidence, 1 March 2022.

[44] Tammy Switucha, Executive Director, Food Safety and Consumer Protection Directorate, Canadian Food Inspection Agency, Evidence, 10 February 2022.

[45] Claire Dawson, Senior Manager, Fisheries and Seafood Initiative, Ocean Wise, Evidence, 15 February 2022.

[49] Sonia Strobel, Co-Founder and Chief Executive Officer, Skipper Otto Community Supported Fishery, Evidence, 15 February 2022.

[51] Sylvain Charlebois, Professor, Agri-Food Analytics Lab, Dalhousie University, As an Individual, Evidence, 3 March 2022.

[52] Government of Canada, Charlevoix blueprint for healthy oceans, seas and resilient coastal communities, 2018; Food and Agriculture Association of the United Nations, Voluntary Guidelines for Catch Documentation Schemes, 2017.