HESA Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

Introduction

It is 2 April 2019 and the sun hangs low in the Winnipeg sky. It should be spring by now, but the wind is still biting. The members of the House of Commons Standing Committee on Health (“the Committee”) are out with the Bear Clan Patrol Inc. in the back alleyways of northern Winnipeg, wanting to see first hand the impact of the methamphetamine crisis that is growing across the country. According to Executive Director Mr. James Favel, the Bear Clan Patrol is a community-based, volunteer-driven safety patrol, whose “mandate is to protect and empower the women, children, elderly and vulnerable members of our community.”[1] The Bear Clan patrols the inner city of Winnipeg five to six nights a week, acting as mentors, first responders, janitors and a liaison between the community and service providers. The organization re-emerged in September 2014 in the wake of the death of Tina Fontaine, a young girl that was exploited and murdered while in the care of Manitoba’s child welfare system. He stated that the goal of the organization “at the time was to interrupt the patterns of exploitation in our community to ensure that what happened to Tina would not happen to anyone else ever again.”[2]

“Sharp!” Someone yells out. A member of the Bear Clan Patrol stops to pick up the needles and other drug-related paraphernalia. The needles are found amidst other garbage that is strewn across the alleyway that divides the rows of boarded up houses. Mr. Favel explains to members of the Committee that the bright colours of the methamphetamine cookers attract children because they look like toys. Volunteers among the group note the location and number of the needles, as well as any weapons found to better understand the drug and crime patterns in the community. Care packages are given to neighbours watching the patrol from their porches and granola bars are handed out to children playing in the local park. The group of volunteers is diverse. One woman is walking to support reconciliation with Canada's Indigenous peoples, while another volunteer is a parent trying to find solace in cleaning up the city as she slowly loses her child to a methamphetamine addiction.

As the patrol for the evening begins to wind down, the group comes across a young woman. She is wearing a tank top and jeans. She carries her belongings in three plastic bags. She is disoriented, and her skin is red from the cold. The Committee learns that methamphetamine keeps a person awake and warm enough to survive cold nights on the street. However, this is not much of a benefit as the drug may also cause psychosis. Not wanting to be pitied, the young woman initially resists the Bear Clan’s help but eventually accepts a care package, a warm jacket and the offer to be taken somewhere safe.

This moment brings into sharp clarity the reasons why on 16 April 2018, the Committee adopted the following motion:

That, pursuant to Standing Order 108(2), the Committee undertake a study on the impacts of methamphetamine abuse in Canada in order to develop recommendations on actions that the federal government can take, in partnerships with the provinces and territories, to mitigate these impacts; that the Committee report its findings and recommendations to the House[3].

As part of its study on the impacts of problematic methamphetamine use across Canada, the Committee held six formal meetings and heard from 34 witnesses between 29 November 2018 and 26 February 2019. In addition, the Committee conducted a total of 15 site visits and informal meetings, which took place in Montréal, Winnipeg, Calgary and Vancouver between 1 and 5 April 2019. During these meetings, the Committee heard from a wide range of stakeholders, including government officials, health care providers, public health experts, representatives of community-based organizations, peer-support workers, law enforcement agency officials, lawyers, judges and individuals with lived experience with substance use and families affected by substance use. The Committee also received ten briefs and 12 background and reference documents from individuals and organizations. The Committee sincerely appreciates the input of the many stakeholders who met with the Committee and their dedication in providing services and supports to our country’s most vulnerable people. The Committee would also like to thank individuals with lived experiences and their families for their courage in sharing their stories, which helps shed a human light on this important issue.

This report summarizes the findings of the Committee’s meetings with stakeholders as well as the recommendations they provided on ways to address methamphetamine use in Canada. The report begins with an overview of methamphetamine and its health effects, as well as its impacts on health care systems and public safety across the country. It then examines the underlying root causes of methamphetamine use and substance use disorders more broadly, such as trauma and adverse childhood experiences; co-occurring mental health conditions; inadequate housing; poverty; and, other social determinants of health. It then looks at the federal government’s role in addressing methamphetamine use in Canada and identifies steps it could take, in collaboration with the provinces and territories and other stakeholders, to address the impacts of methamphetamine use, in the following areas: leadership, prevention, harm reduction, treatment and recovery, criminal justice, housing and social supports, data collection and surveillance.

Overview of Methamphetamine and its health effects

According to the Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction (CCSA), “methamphetamine is a synthetic drug that is classified as a central nervous system (CNS) stimulant or psychostimulant.”[4] Methamphetamine was originally developed as a prescription drug used to treat medical conditions including asthma, epilepsy, obesity, schizophrenia, narcolepsy and hyperactivity in children, but its use was discontinued in the 1950s and 1960s because of its high addiction potential.[5] The drug is currently produced in clandestine laboratories with commonly available precursor chemicals, such as ephedrine, pseudoephedrine, lithium and fertilizer.[6] The drug is sold in a variety of forms, including powder, tablets, and rock-like chunks. Depending upon its form, it may be snorted, injected, ingested or smoked.[7]

Stimulants act on the central nervous system by releasing large amounts of the neurotransmitter dopamine, creating feelings of euphoria and wakefulness.[8] Methamphetamine releases larger amounts of dopamine in comparison to other stimulants, such as amphetamines and cocaine, resulting in a stronger physiological response among users.[9] As a result, the high associated with the drug can last up to 12 hours.[10] The Committee heard from witnesses that methamphetamine also acts as a sexual stimulant resulting in riskier sexual behaviour among users, including engaging in sex with a greater number of sex partners and not taking precautions to prevent sexually transmitted infections (STIs).[11] As a result, the Committee heard that the rates of STIs are 50% higher among users than in the rest of the population, particularly among men who have sex with men, but increasingly in women as well.[12] The Committee heard that this was also contributing to a rise in rates of congenital syphilis among children whose mothers are using methamphetamine.[13] Other short-term physical effects of the drug include increased heart rate and breathing; rising body temperature; and decreased appetite.[14]

In terms of addiction potential, the Committee heard that methamphetamine is highly addictive in comparison to other drugs:

If you look at the general population, it's estimated that 10% of people who use methamphetamine will develop a substance use disorder immediately, just with one use. Typically, it's 10% within a lifetime with most substances, but the reinforcing effects of the methamphetamine are very, very strong. If you look at dopamine release in the brain with sex, it would be 10 times that with regards to what people get from methamphetamine, so it's 10 times orgasm and very reinforcing.[15]

Individuals who had engaged in methamphetamine use further confirmed to the Committee during informal meetings across the country that they found the drug extremely addictive in comparison to other stimulants such as cocaine. They said it took over their minds in matter of months after first use. Ms. Kim Longstreet, President, RJ Streetz Foundation also stated to the Committee:

For 11 years now I've watched my son slowly succumb to the world of drugs, to marijuana, cocaine, ecstasy, crack and meth. Of all the drugs he has used, meth is the one that won't allow him to function in life. With the other drugs, he was still trying to get his education, play basketball and hold down a job. Meth took everything away except his need for the drug.[16]

“For 11 years now I've watched my son slowly succumb to the world of drugs, to marijuana, cocaine, ecstasy, crack and meth. Of all the drugs he has used, meth is the one that won't allow him to function in life. With the other drugs, he was still trying to get his education, play basketball and hold down a job. Meth took everything away except his need for the drug.”

Ms. Kim Longstreet, President, RJ Streetz Foundation

Over the long term, the Committee heard that the most significant impact of methamphetamine use is the risk of psychosis or psychotic symptoms that may occur with chronic or heavy use of the drug.[17] Though estimates vary, the Committee heard from the Addictions Foundation of Manitoba that between 8% and 46% of regular users may experience psychosis.[18] The Committee heard that psychosis involves a range of behaviours including hearing voices, speaking gibberish, losing track of time, losing touch with reality and agitation.[19] At its more extreme end, methamphetamine induced psychosis results in paranoia, hallucinations and violent behaviour.[20] Dr. Tim Ayas, Clinical Assistant Professor, University of Calgary explained to the Committee that studies[21] have shown that 25%-30% of methamphetamine users who experience drug-induced psychosis end up developing primary psychosis within eight years.[22]

Both Dr. Peter Butt, Associate Professor, College of Medicine, University of Saskatchewan and Dr. Susan Burgess, Clinical Associate Professor, University of British Columbia, Vancouver Costal Health explained to the Committee that the psychosocial instability caused by the drug means that individuals with HIV are no longer able to adhere to their antiretroviral treatments and are dying of AIDS as a result.[23] Meanwhile, as is the case with other drugs, injection of methamphetamine also poses risks of transmission of HIV and Hepatitis C, as well as other blood-borne infections.[24]

Impacts of Methamphetamine use across the country

The Committee heard form Dr. Matthew Young, Senior Research and Policy Analyst, Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction (CCSA) that approximately 0.2% of Canadians self-reported using methamphetamines in the past year between 2015 and 2018.[25] However, he further explained that this “national survey data tells only a very small part of the story. There is considerable variation in rates of methamphetamine use and problematic use tends to be concentrated among populations that are unrepresented in national surveys.”[26] While there has been an increase in the availability, use and harms associated with methamphetamine use across Canada in the last 10 years, he explained that the impacts of methamphetamine are currently being felt most acutely in the western provinces.[27]

Dr. Ginette Poulin, Medical Director, Addictions Foundation of Manitoba explained to the Committee that there had been a 104% increase in reported methamphetamine use in Manitoba within the last year among adults, while 48% of youth seeking treatment for addiction in the province report that methamphetamine is their primary substance of use.[28] She further explained that there had been a 1,700% increase in emergency room visits in the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority and a three- or four-fold increase in deaths associated with methamphetamine use.[29] The Committee heard from Ms. Darlene Jackson, President, Manitoba Nurses Union that methamphetamine use in the province is cutting across all walks of life:

A nurse in Portage la Prairie told me, « It’s all races, all ages. Even the people you least suspect who drive the fanciest vehicles, who have the best jobs, they are even trying it. It’s a problem.[30]

She further explained that the rise in methamphetamine use in Manitoba is also having a significant negative impact on emergency departments in the province as they are often the only location where users can access any kind of treatment.[31] However, when these individuals arrive at the emergency department, they are in distress and can start behaving erratically or violently, which threatens the safety of other patients and health care providers.[32] The health care and security personnel required to deal with methamphetamine users means that other patients awaiting care face longer wait-times. In addition, health care providers experience higher rates of workplace stress and burnout.[33] These points were also raised by health care providers during the Committee’s informal meeting at the Rapid Access to Addictions Medicine Clinic in Winnipeg. They explained to the Committee that many of them had been subject to violence or harmed at work as a result of rising methamphetamine use in the city.[34]

“A nurse in Portage la Prairie told me, ‘ It’s all races, all ages. Even the people you least suspect who drive the fanciest vehicles, who have the best jobs, they are even trying it. It’s a problem.’”

Ms. Darlene Jackson, President, Manitoba Nurses Union

The Committee heard from Dr. Young that the rate of individuals being hospitalized for methamphetamine use increased by almost 800% between 2010 and 2015 in Alberta.[35] In informal meetings with representatives from Alberta Health Services, the Committee also learned that among individuals who came to emergency departments between July 2015 and January 2019 for urgent methamphetamine-related health issues, 26% of them experienced mental or behavioural disorders as result of their methamphetamine use.[36] In addition, the majority of individuals presenting to the emergency department in relation to methamphetamine use in Alberta during this time period were socially and materially deprived.[37] According to the Calgary Homeless Foundation, 65% of individuals in detoxification programs in Calgary in 2018-2019 were withdrawing from methamphetamine, in comparison to 39% in 2016-2017.[38] Meanwhile, approximately 50% of individuals in shelters in Calgary in 2018-2019, were also using methamphetamine, posing challenges to staff because of their high levels of paranoid, aggressive and violent behaviours.[39]

According to Lisa Lapointe, Chief Coroner, BC Coroners Service, the picture is somewhat different in British Columbia as the drug supply continues to be contaminated primarily with fentanyl.[40] As in other western provinces, British Columbia experienced a similar increase in hospitalization rates for methamphetamine use, increasing by almost 500% between 2010 and 2015.[41] Between 2010 and 2017, methamphetamine-related overdose deaths also increased in British Columbia from 23 to 283 individuals.[42] However, Ms. Lapointe explained that fentanyl was detected in four out of five methamphetamine-related overdose deaths from 2016 to 2018, which is likely driving the increase of methamphetamine-related deaths.[43] In terms of demographics, the Committee heard that most methamphetamine-related overdoses between 2016-2018 were among males (78.4%). The majority of methamphetamine-related overdoses occurred in individuals ranging in age from 30 to 49.[44] Ms. Sarah Blyth, Executive Director, Overdose Prevention Society explained to the Committee that approximately half of individuals using drugs in the Downtown East Side of Vancouver are taking methamphetamine and her organization sees approximately 200 methamphetamine users per day.[45]

The Committee heard that other parts of the country are also experiencing increasing rates of methamphetamine use, but only in some sectors of the population. Dr. Réjean Thomas, Chief Executive Officer, Clinique medical l’Actuel, explained that methamphetamine use is a rising concern among men who have sex with men in Montréal.[46] According to Dr. Thomas, 30% of his clients engage in “chemsex” or party and play (PnP) where they are under the influence of methamphetamine in combination with other drugs and alcohol while having sex. Dr. Thomas said he is now seeing between one and five patients a day who have developed an addiction to both methamphetamine and sex as a result.[47]

In Toronto, Dr. Eileen de Villa, Medical Officer of Health, City of Toronto said that opioids and cocaine are more commonly used in Toronto than methamphetamines and further noted that more than one drug was often involved in drug overdoses due to the contamination of the drug supply with fentanyl.[48] However, according to a Health Canada survey, 30% of street-involved adults in Toronto indicated that they use methamphetamines.[49] In addition, she explained that there had been an increase in individuals in Toronto seeking treatment for methamphetamine use, from 4% in 2012 to 12% of those seeking treatment for substance use in 2018. [50]

With respect to methamphetamine use within Indigenous communities across the country, the Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction’s written submission explained that data from the National Report of the First Nations Regional Health Survey had shown that past-year use of methamphetamine among First Nations aged 18 and older was approximately 1.2% in 2015-2016.[51] Among First Nations youth aged 12-17, past-year use of the drug in 2015-2016 was 0.6%. However, the Committee heard from witnesses that some Indigenous communites across Canada are increasingly “reporting significant health and safety issues related to meth use.”[52] In his appearance before the Committee, Mr. Damon Johnston, Chair, Board of Governors, Addictions Foundation of Manitoba explained that methamphetamine use is negatively impacting Indigenous communities in Winnipeg:

I’m president of the Aboriginal Council of Winnipeg. In that role, I am very aware of the impact of these powerful drugs on members of our community and other vulnerable communities, such as the homeless population and people in poverty. They are the least equipped to meet these challenges-and they’re very real. In my job, my role, I interact with families in our community in many different ways. I’ve had direct experience with some of the nasty outcomes, effects, directly on families, particularly on mothers and children. It’s a serious issue.[53]

In its informal meeting with Alberta Health Services, Dr. Esther Tailfeathers, Medical Lead, Population, Public, Indigenous Health, Strategic Care Network explained that the Blood Tribe in Lethbridge Alberta had declared a state of emergency due to the opioid crisis in 2014, but more recently, the community had observed a spike in methamphetamine use. She further explained that often individuals in the community are polysubstance users, including using both methamphetamine and fentanyl in combination to offset the effects of each individual drug.[54] During its informal meeting with the Vancouver Native Health Society, Dr. Aida Sadr, Family Physician said that over the past ten years, there had also been a rise in methamphetamine use in the Downtown East Side of Vancouver, particularly among Indigenous populations using the organization’s health services.[55]

In terms of the impact methamphetamine use is having on public safety, Ms. Suzy McDonald, Assistant Deputy Minister, Opioid Response Team, Department of Health explained that there had been a 365% rise in methamphetamine seizures by police across the country between 2007 and 2017.[56] The Committee heard that methamphetamine on the streets in Canada mainly comes from Mexico through organized crime, with some domestic production depending upon the region.[57] Steve Barlow, Chief Constable, Calgary Police Service explained that there is an excess of supply of the drug in the country, which means that the price of methamphetamine has dropped from $100 per gram to $50 per gram and $5 a hit.[58] The low price of the drug coupled with its long-lasting effects means that individuals are able to get more “bang for the buck,” which is driving demand for the drug.[59] According to representatives of the Winnipeg Drug Treatment Court, methamphetamine is also used as a cutting agent in other drugs such as cocaine. Consequently, individuals often end up purchasing and using methamphetamine unknowingly as a result.[60]

The Committee heard from Chief Steve Barlow that while “fentanyl is a community health crisis, meth is a crime and safety issue.”[61] The Committee heard that methamphetamine use is linked to rising rates of stolen vehicles, impaired driving and unprovoked violent attacks on by-standers. He further noted that individuals using methamphetamine “are not being arrested for possession. These people are being arrested for other crimes that relate to their addiction problem.”[62] The long-lasting effects of the drug also means that individuals are able to commit large “volumes of crime beyond what could otherwise be expected.”[63] In addition, he explained that a lack of mental health and substance use treatment options means that often individuals are arrested for their drug-related crime but are subsequently released to re-commit the same crimes, placing a strain on police resources.[64]

“Fentanyl is a community health crisis, meth is a crime and safety issue.”

Chief Constable Steve Barlow, Calgary Police Service

Finally, the Committee heard from Lee Fulford, Detective Staff Sergeant, Organized Crime Enforcement Bureau, Ontario Provincial Police that the dismantling of toxic clandestine methamphetamine laboratories also has a significant impact on public safety, requiring up to 20 emergency services personnel to dismantle a small lab, where as a large profit-driven operation can involve 45 police and fire staff and take up to three days.[65] Staff Sergeant Fulford further explained that one pound of methamphetamine production creates approximately six pounds of toxic waste, which is often dumped, causing environmental contamination and health hazards for the public.[66]

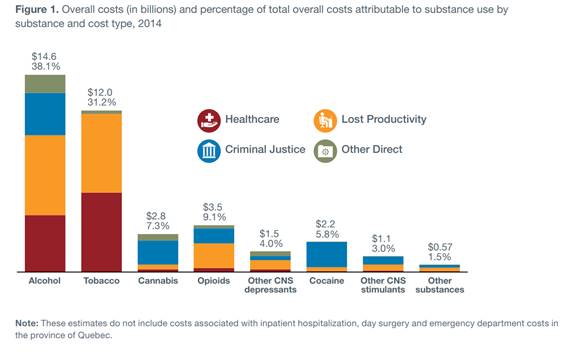

Though the Committee heard that there is limited information available on the economic costs of methamphetamine use specifically, the Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction and the University of Victoria has undertaken an analysis of the economic impacts of central nervous system stimulants broadly. In 2014, the total economic costs of substance use in Canada was estimated to be $38.4 billion.[67] The category of “Other central nervous system stimulants”, which includes methamphetamine but not cocaine, accounted for 3% of these costs or $1.1 billion (see Figure 1). According to the study, the largest economic costs of the use of CSN stimulants other than cocaine was loss of productivity ($0.5 billion), followed by criminal justice costs ($0.6 billion) and health care costs ($0.1 billion).[68]

Figure 1: Overall costs (in billions) and percentage of total overall costs attributable to substance use by substance and cost type, 2014

Source: Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse and Addiction and the University of Victoria, Canadian Substance Use Costs and Harms, 2007-2014, 2018, p.8, submitted to HESA by the Calgary Homeless Foundation.

Underlying Causes of Problematic Methamphetamine Use in Canada

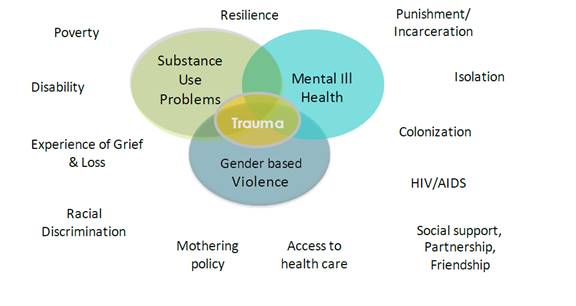

The Committee learned that a wide range of factors are contributing to the rise of problematic methamphetamine use across the country. The Committee heard from witnesses that while some individuals may use methamphetamines for personal enjoyment, enhanced sociability, or greater concentration without significant negative consequences, others are more susceptible to problematic use of the drug and its associated harms.[69] Witnesses explained that these individuals and population groups may be more susceptible to problematic use of the drug and its associated harms because of various interrelated social, cultural and economic factors that can contribute to health inequities, often referred to as the social determinants of health.[70] The Committee heard that the specific determinants of health related to the development of problematic substance use and addiction include but are not limited to: adverse early childhood experiences; trauma; colonization; mental health conditions; poverty and homelessness; and sex and gender (see Figure 2).[71] Witnesses explained that a better understanding of how these factors contribute to methamphetamine use is necessary to determine how to respond to its rising use and impacts on public health and safety across the country.[72] An overview of these factors as they relate to methamphetamine use is provided in the sections below.

Figure 2. The Social Determinants of Health Matter

Source: Centre of Excellence for Women’s Health, “Written brief to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Health regarding the study of the impact of methamphetamine use in Canada and LGBTQ health in Canada,” 5 April 2019.

Trauma

Dr. Sheri Fandrey, Knowledge Exchange Lead, Addictions Foundation of Manitoba, Canadian Community Epidemiology Network on Drug Use, explained to the Committee that:

Prior or ongoing trauma is common in people who use methamphetamine at a high intensity. In many cases, methamphetamine use is a direct response to experiences of physical and sexual abuse and trauma.[73]

Dr. Victoria Creighton, Clinical Director, Pine River Institute, further explained that smaller childhood traumas are also associated with drug addiction:

There’s big-T trauma and the small-t trauma. Every child we have had, has had some form of trauma, and a lot of it often comes through the mis-recognition that is occurring within their communities, within the family, of not being seen and not being held. There are these underlying yearnings to belong, to be seen and valued for who they are. When that is met, the kids actually thrive and grow.[74]

In their presentation to the Committee, Drs. Tim Ayas, Esther Tailfeathers and Michael Trew from Alberta Health Services further explained to the Committee that the Kaiser Permanente and United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE) Study[75] demonstrated that individuals who suffered adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are more likely than individuals who did not suffer ACEs to adopt risky or negative health behaviours later in life that can lead to addiction and other chronic diseases. They explained that the ACE study was based upon a questionnaire that surveys the number of ACEs an individual may have experienced before the age of 18 years in three different categories: childhood abuse, neglect and household challenges (see Figure 3). Based upon a scale of 10, one point is given for each type of ACE within these different categories. A higher number of ACEs in these different areas is associated with a higher risk of developing a drug addiction or other chronic diseases. According to Drs. Tim Ayas, Esther Tailfeathers and Michael Trew, individuals seeking treatment for addiction in Alberta have relatively high scores of five or more on the ACE Survey.[76]

Figure 3. Ten Types of Adverse Childhood Experiences Associated with the Risk of Developing a Substance Use Disorder

Source: adapted from the following document: United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Adverse Childhood Experiences: Looking at how ACE affect our lives or society

Similarly, the Committee heard from individuals with lived experience that some of them grew up in fractured families and often their methamphetamine use began from a desire to fit in with or belong to their peer group. They also explained that they experienced significant trauma resulting from their methamphetamine use, either from the behaviours that they engaged in while under the influence of drugs or to obtain the drugs. They were also often in dangerous situations as result of their drug use and were either subject to or a witness of violence.

“There’s big-T trauma and the small-t trauma. Every child we have had, has had some form of trauma, and a lot of it often comes through the mis-recognition that is occurring within their communities, within the family, of not being seen and not being held. There are these underlying yearnings to belong, to be seen and valued for who they are.”

Dr. Victoria Creighton, Clinical Director, Pine River Institute

The Committee heard from the Vancouver Native Health Society that methamphetamine use and substance use more broadly among Indigenous Peoples is also a product of intergenerational trauma arising from colonialism, including from residential school experiences; the placing of Indigenous children in foster care in the “Sixties Scoop”[77]; forced dislocation; and cultural, social and economic disempowerment.[78] The Vancouver Native Health Society’s reference document stated that colonization has meant that in comparison to the general population, Indigenous peoples experience higher rates of incarceration and children in foster care; and Indigenous women are nearly three times more likely to experience violent victimization than are non-Indigenous women.[79] Dr. Esther Tailfeathers, Alberta Health Services further explained to the Committee that these impacts of colonization means that Indigenous peoples have very high scores on the ACE, ranging from six to ten, placing them at very high risk for substance use and addiction.[80]

Dr. Sheri Fandrey, Canadian Community Epidemiology Network on Drug Use, explained that because methamphetamine use is often a response to trauma, services and resources to address the problem must be “trauma-informed”, which means that the care and treatment offered recognizes that trauma and other related issues may be underlying factors for substance use and may limit an individual’s ability to abstain from substance use.[81]

Co-occurring Mental Health conditions

While methamphetamine use itself can be associated with psychotic symptoms, the Committee also heard that individuals using the drug may also be doing so because of a co-occurring mental health condition or disorder. Some individuals with experiences of methamphetamine use explained to the Committee that their use of methamphetamine arose out of undiagnosed mental health conditions, including bipolar disorder, anxiety and depression. In their presentation to the Committee, Drs. Tim Ayas, Esther Tailfeathers and Michael Trew from Alberta Health Services explained that 7.2% of individuals visiting emergency departments for methamphetamine use between July 2015 and January 2019 had an anxiety disorder, 6.8% had schizophrenia or related psychotic disorder, and 4.6% had mood disorders.[82] Dr. Susan Burgess, Clinical Associate Professor, University of British Columbia, Vancouver Coastal Health, told the Committee that many of the individuals living in the Downtown East Side of Vancouver live there as a result of the de-institutionalization of psychiatric care in the province. These individuals were introduced to methamphetamine while living there and found that the drugs produced psychiatric benefits for them:

If you happen to be schizophrenic and you use crystal meth, all of a sudden you feel like a king. What a wonderful feeling for someone who may have been institutionalized and has difficulty making it through a day.[83]

Homelessness

The Committee heard from witnesses that methamphetamine use is prevalent among the homeless and those who live or sleep on the street. As these individuals face high rates of assault and theft of their property, they often resort to using methamphetamines in order to remain awake through the night. Ms. Karen Tuner, Board Member, Alberta Addicts Who Educate and Advocate Responsibly, explained to the Committee that some homeless individuals also use methamphetamine to survive the cold nights while living on the streets:

During the winter in Edmonton, when the temperatures are 30 below, people who are experiencing homelessness use meth just to survive. This means using it to stay awake all night to avoid freezing to death.[84]

“During the winter in Edmonton, when the temperatures are 30 below, people who are experiencing homelessness use meth just to survive. This means using it to stay awake all night to avoid freezing to death.”

Ms. Karen Tuner, Board Member, Alberta Addicts Who Educate and Advocate Responsibly

Similarly, Dr. Eileen de Villa, Medical Officer of Health, City of Toronto explained that while substance use is prevalent among homeless people, it is a cause of homelessness in only a small number of cases (approximately 5%) in the city.[85] Rather, most homeless individuals use substances to address unmet health care and other needs.[86] She explained that women in particular who are homeless in Toronto have indicated that they use methamphetamine to stay awake at night to protect themselves.[87]

Poverty

Mr. James Favel, Executive Director, Bear Clan Patrol Inc. also explained that rising methamphetamine use in inner city communities in Winnipeg and across the country is a response to widespread poverty and its associated lack of social, cultural and economic opportunities:

The poverty and disconnectedness in our communities triggers addiction in our community members. That addiction feeds the random violence, feeds the rampant poverty, property crime, and it self-perpetuates: street, hospital, prison, repeat. Safe consumption sites, needle exchange programs, 12-step programs, treatment opportunities, these are all good things, but if you're hungry or you woke up on a friend's couch that's another challenge. If you can't afford transportation to and from programming, job interviews, doctors' appointments, and even banks and shopping centres, these are beyond the reach of many of our community members. If those underlying issues related to poverty are not addressed there will be no meaningful progress.[88]

“Safe consumption sites, needle exchange programs, 12-step programs, treatment opportunities, these are all good things, but if you're hungry or you woke up on a friend's couch that's another challenge.[…] If those underlying issues related to poverty are not addressed there will be no meaningful progress.”

Mr. James Favel, Executive Director, Bear Clan Patrol Inc.

Mr. Favel also explained to the Committee that drugs and related-paraphernalia are more accessible in low-income neighbourhoods than banks and stores that sell produce and wholesome foods.[89] Other witnesses explained that methamphetamine use is also more prevalent in poorer or lower income communities because of its low price. Dr. Peter Butt, Associate Professor, College of Medicine, University of Saskatchewan noted:

What we see with methamphetamine is that it seems to be directed toward poorer communities, which is perhaps why we see it more on the plains.[90]

Similarly, Detective Sergeant John Pearce, Sarnia Police Service explained: “the other thing with the drug that I find makes it attractive in this particular community is that we have a very blue-collar socio-economic makeup, and this is a cost-effective, affordable and easily accessible drug.”[91]

Sex and Gender

The Committee also heard from witnesses that there are sex and gender-related issues associated with methamphetamine use. According to Dr. Ginette Poulin, Medical Director, Addictions Foundation of Manitoba, methamphetamine use is higher among women than men in the province (31% of the Foundation’s female clients versus 16% of male clients for past-year substance use in 2017).[92] According to Lorraine Greaves, Senior Investigator and Nancy Poole, Director of British Columbia’s Centre of Excellence for Women’s Health, women are more likely to start using methamphetamine at younger ages than men and do so to deal with depression or emotional or family problems or to lose weight, whereas men report using the substance to be more productive or because a family member uses the substance.[93] They also explained that women’s substance use is also influenced by power dynamics in their relationships with men. Women often begin using drugs if their partner is using drugs. They also face pressure from them to obtain drugs through prostitution or other means. In addition, men are often “first on the needle,” which means they end up transmitting their blood-borne infections including HIV and Hepatitis C to female partners when sharing needles with them.

However, Dr. Poulin explained that high rates of methamphetamine use among young girls and women have broader implications for families in the province, contributing to the already high rates of apprehension of children and placement in foster care.[94] Lorraine Greaves and Nancy Poole from British Columbia’s Centre of Excellence for Women’s Health explained that women using substances are often unaware that they are pregnant at the time. In addition, once they have children, they do not seek treatment for substance use because they fear that their children will be taken away by child and family services. Finally, once the children are apprehended, the mothers are very traumatized from the experience, which gives rise to further substance use.[95] Women recovering from methamphetamine addiction echoed this observation to the Committee explaining that often their greatest challenge is the removal, by child and family services, of visitation privileges with their children, which can trigger the mothers to return to substance use. Consequently, both Dr. Greaves and Annetta Armstrong, Executive Director, Indigenous Women’s Healing Centre,[96] explained that child apprehension policies and approaches need to be supportive of the mother’s recovery needs as well as focus on keeping the family together.

As noted earlier, the Committee learned that among men who have sex with men, methamphetamine is used as both a party drug and a sexual stimulant, which can lead to an addiction to both the drug and the sexual experiences that arise from it. In meeting with Head & Hands, a community-based organization in Montreal that provides health, social and legal services to youth, the Committee learned that “chemsex” or party and play among this population group arises, in part, from a lack of self-acceptance arising from belonging to a stigmatized population group that experiences discrimination and prejudice.[97] Addressing problematic methamphetamine use among this population group is challenging because it requires both treatment of drug addiction and changes to sexual behaviour.[98]

With respect to substance use more broadly within the LGBTQi2 (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex and Two-Spirit) communities, Lorraine Greaves, Senior Investigator and Nancy Poole, Director of British Columbia’s Centre of Excellence for Women’s Health, explained to the Committee that lesbian people experience higher than average rates of substance use; and bisexual girls and women have the highest rates of substance use and addiction in both Canada and the United States.[99] They explained that higher rates of substance use within these populations may also be a reflection of discrimination and stigma that these individuals face.[100]

The Federal Role in Addressing Methamphetamine Use in Canada

In their appearance before the Committee, officials from Health Canada, the Department of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) explained the federal government’s role in addressing methamphetamine use in Canada and what steps are being taken to address the issue as part of the Canadian Drugs and Substances Strategy.

Regulation of Methamphetamine under the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act

The Committee heard from Ms. Michelle Boudreau, Director General, Controlled Substances Directorate, Department of Health that the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act (CDSA or the Act),[101] Canada’s federal drug control statute, provides a legislative basis for the control of substances that can alter mental processes and may cause harm to the health of an individual or society when abused or diverted into the illicit market.[102] Under the CDSA, methamphetamine production, possession, trafficking, and importation/exportation (with certain exceptions) are illegal in Canada. Methamphetamine is listed under Schedule I of the CDSA. The maximum penalty for possession for Schedule 1 controlled substances is seven years, and life imprisonment could be imposed for trafficking, production, importation or exportation, or possession for the purpose of export.[103]

In addition, she explained that the precursors used to produce methamphetamine are controlled under the CDSA and its Precursor Control Regulations.[104] Under these regulations, only licensed dealers may sell Class A precursors, such as ephedrine, pseudoephedrine, and red and white phosphorus, used in the production of methamphetamine.[105] A person found guilty of importing, exporting, or possessing for the purpose of export precursors used to produce methamphetamine without authorization faces up to 10 years of imprisonment.[106]

Canadian Drugs and Substances Strategy

Ms. Suzy McDonald, Assistant Deputy Minister, Opioid Response Team, Department of Health explained to the Committee that the Government of Canada is addressing all forms of problematic substance use, including methamphetamine use, through the Canadian Drugs and Substances Strategy.[107] She explained that this Strategy has five main areas for action: prevention, harm reduction, treatment, enforcement, collection of data and research evidence. An overview of what actions are being taken in each of these areas to address problematic methamphetamine use in Canada is provided in the sections below.

Prevention

According to Ms. McDonald, the federal government is focusing on preventing methamphetamine use by raising public awareness about the risks and harms associated with the drug’s use.[108] She also explained that the federal government also recognizes the need to move beyond public awareness to address the social determinants of health that underlie problematic substance use and is committed to working collaboratively to “develop upstream interventions to prevent substance use before it begins.”[109] To address the social determinants of health, the Committee heard that her department has been working with Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC) and other departments in the development of Opportunity for all-Canada’s First Poverty Reduction Strategy[110] and Reaching Home: Canada’s Homelessness Strategy,[111] which is a component of the federal government’s broader housing strategy entitled Canada’s National Housing Strategy: A place to call home.[112] In terms of the federal housing strategy, she said that the department was able to change the requirements for some of the housing programs so that individuals are no longer required to be substance free in order to be eligible for social housing.[113] The Committee also heard that the Chief Public Health Officer is focused on addressing resiliency in youth and addressing mental health issues in early childhood.[114]

Harm Reduction

Harm reduction is defined as “an approach or strategy aimed at reducing the risks and harmful effects associated with substance use and addictive behaviours for the individual, the community and society as a whole.”[115] Ms. McDonald explained that the Public Health Agency of Canada is providing $30 million over five years to fund evidence-based harm-reduction measures that focus on reducing the risk of contracting blood-borne infections, such as HIV and hepatitis C, from the sharing of drug-using equipment such as syringes and pipes among individuals who use drugs.[116] This amount includes support for Supervised Consumption Sites (SCS), which are places that allow individuals to consume illicit substances, provide clean supplies for drug consumption and offer medical services to respond to drug overdoses.[117] To operate in Canada, SCS must obtain an exemption from the Minister of Health under section 56.1 of the CDSA through an application to Health Canada.[118]

Ms. McDonald explained that addressing the stigma that methamphetamine users face is another critical component of harm reduction.[119] She explained that the physical effects of methamphetamine use, such as scars, coupled with the unpredictable behaviour of users, creates a negative image of these individuals. As a result, they face barriers when accessing treatment and other harm reduction and social support services. She explained that as part of Budget 2018, the federal government invested $18 million over five years for actions to address stigma towards people who use drugs, including a national anti-stigma campaign and training for law enforcement officials. She noted that “although much of what Health Canada is doing on stigma is done in the context of the opioid crisis, we are confident that it will have a positive impact on other areas.”[120] Finally, she explained that the Good Samaritan Drug Overdose Act “encourages people to seek help in the event of a drug overdose by providing some legal protection for those who experience or witness a drug overdose.”[121]

Treatment

Ms. Macdonald explained to the Committee that the opioid crisis had made it clear that there are not enough drug treatment services to meet the demand.[122] Though the exact size of the significant gap in the availability of treatment services across Canada is currently unknown, she explained that there were 220,000 people waiting to have access to addiction treatment services in Canada in 2014 alone. To help the provinces and territories improve access to addiction treatment services in Canada, the Committee heard that the federal government established the $150 million Emergency Treatment Fund with the provinces and territories in Budget 2018.[123] To obtain these funds, provinces and territories enter into bilateral agreements with the federal government in which they agree to match these funds and outline their priorities for the funds’ use.[124] All provinces and territories have signed bilateral agreements to secure part of this one-time investment in treatment for drug addiction.[125] Ms. Macdonald explained that while this fund was set up to address the opioid crisis, some jurisdictions, including Manitoba and Saskatchewan, are using these funds to address methamphetamine use.[126]

In addition, the Committee heard that in Budget 2018, the federal government also provided $200 million over five years, and $40 million in ongoing funding for expanding mental health and drug treatment services in First Nations communities.[127]

Enforcement

The Committee also heard from Ms. McDonald that the RCMP and the Canadian Border Services Agency (CBSA) and Correctional Services Canada are also working to enforce the CDSA.[128] The RCMP’s national chemical precursor diversion program works with industry partners to help prevent the diversion of precursor chemicals used by suspected criminals and organized crime groups to produce methamphetamine. In addition, CBSA is working with international and domestic law enforcement agencies to prevent methamphetamine from being trafficked into Canada from other countries such as Mexico. Finally, Correctional Services Canada is taking steps to reduce the demand among federal inmates for methamphetamines, by working to prevent their entry into prisons, raising awareness of the harms of the drugs and promoting treatment and harm-reduction approaches such as needle-exchange programs.

Research and Surveillance

Ms. McDonald explained to the Committee that research and surveillance are also critical components of the federal government’s response to substance use, including methamphetamine use.[129] She explained that the Canadian Institutes of Health Research is funding a pilot project whose goal is to identify effective interventions to reduce methamphetamine use among men who have sex with men. In addition, she explained that Health Canada’s Substance Use and Addictions Program provides grants and contributions to provinces, territories and non-governmental organizations that support evidence-informed and innovative initiatives targeting a broad range of legal and illegal substances. Finally, the federal government is working towards developing a Canadian drugs observatory that would “act as a central hub to provide a comprehensive picture of the current drug situation in Canada” to identify emerging drug issues, track public health interventions and support data sharing.[130] She also indicated that the federal government is working with provincial and territorial governments and other stakeholders to identify ways of targeting data and research initiatives to reach marginalized populations.

The Way Forward: What the Committee Heard

While witnesses recognized the efforts that the federal government has been taking to address substance use in Canada through the Canadian Drugs and Substances Strategy, they said much more is needed to be done to address methamphetamine use in Canada, which is quickly escalating into a crisis in some communities. They identified seven main areas where the federal government could take further steps to address problematic methamphetamine use, including in leadership and coordination, prevention, harm reduction, treatment and recovery, housing and social supports, criminal justice issues and research and surveillance. A summary of witness testimony and recommendations in these areas is provided in the sections below.

Leadership and Coordination at the National Level

The Committee heard from witnesses that there is a need for the federal government to promote greater collaboration among provincial and territorial governments, municipalities and front-line service provider organizations to ensure that federal funding and strategies related to addressing substance use are making a difference on the ground. In his appearance before the Committee, Mr. Brian Bowman, Mayor, Office of the Mayor, City of Winnipeg explained that addressing methamphetamine use requires greater collaboration across municipal, provincial and federal levels of government because each have different roles and responsibilities in addressing health and social aspects of substance use.[131] Consequently, the Committee heard that the City Council of Winnipeg had called for a tri-government-level methamphetamine task force and a national strategy on illicit drugs, which would include methamphetamine and not just opioids.[132] The Committee notes that in December 2018, the Government of Manitoba, in partnership with the Government of Canada and the City of Winnipeg, announced the creation of the Illicit Drug Task Force, which is expected to report in June 2019.[133] However, during its visit to Winnipeg on 2 and 3 April 2019, the Committee heard from community-based organizations and frontline workers that they are not participating in the task force and they expressed concerns that its recommendations may not reflect the needs on the ground.[134]

Similarly, the Committee heard from witnesses appearing before the Committee that despite recent federal investments in mental health and addiction through both the Emergency Treatment Fund and the federal government’s 10-year bilateral health agreements with the provinces and territories, which include five billion dollars in funding over a ten year period for mental health and addiction initiatives, this funding is not necessarily translating into more treatment services on the ground. Damon Johnston, Chair, Board of Governors, Addictions Foundation of Manitoba (AFM) articulated:

In 2018 we know that Canada and Manitoba announced a new health transfer agreement. Within the agreement, there was an allocation to the province of approximately $181 million over 10 years for improving mental health and addictions services. At this time, AFM and our RHAs have been directed to reduce annual budgets by 1% to 4%. This raises the question of where the federal money in the new agreement is being directed.[135]

Dr. Ginette Poulin, Medical Director, Addictions Foundation of Manitoba therefore recommended that if federal funds are to be provided to the provinces they should be distributed in a manner whereby “we can see the accountability and the transparency of those funds and see them go directly to services.”[136] One possible approach would be to identify a particular percentage of funds that would go directly to organizations providing services on the ground.[137]

Finally, the Committee also heard from Mayor Bowman that there needs to be greater collaboration across federal, provincial and territorial and municipal governments to address the social determinants of health in the context of methamphetamine use, particularly the intersections among mental health, addiction and homelessness.[138] The Calgary Homeless Foundation similarly called for a federal, provincial and territorial table on homelessness and an integrated strategy on strengthening the determinants of health and well-being.[139]

Prevention

Public Awareness

The Committee heard from witnesses that there is a need to raise public awareness about the harms of methamphetamine to help prevent use of the drug. Detective Sergeant John Pearce, Sarnia Police Service, explained to the Committee that many younger people are unaware of the harms of methamphetamine because they associate it with prescription drugs and the drug has been glamourized through Hollywood productions.[140] In addition, Mr. Vaughan Dowie, Chief Executive Officer, Pine River Institute, articulated: “Public education should always be a component of any substance use approach and should provide real and believable information about the impact of the substance to young people. Otherwise, we rely on word of mouth and bad information that minimizes potential harms.”[141] In addition, Ms. Kim Longstreet, President, RJ Streetz Foundation, explained that raising awareness of the harms of methamphetamine is also necessary to help mobilize communities to address the issue:

I have been advocating non-stop to raise awareness about meth and its impacts on a community. I see this advocacy as contributing to my community’s willingness to address the meth issue we currently face.[142]

The Committee heard that there needs to be greater public awareness of what substances are in the drug supply so that individuals do not end up taking the drug unknowingly.[143] The Committee learned during its informal meetings across the country that front-line service providers are trying to communicate trends in the drug supply by sending out text alerts to mobile phones and posting flyers and providing drug checking services so that users can be aware of the contents of their drugs.[144]

Building Resiliency among Youth, Families and Communities

“I have been advocating non-stop to raise awareness about meth and its impacts on a community. I see this advocacy as contributing to my community’s willingness to address the meth issue we currently face.”

Ms. Kim Longstreet, President, RJ Streetz Foundation

Witnesses also outlined ways of preventing methamphetamine use by building resiliency and protective factors in children, youth, families and communities. Drs. Tim Ayas, Esther Tailfeathers and Michael Trew recommended that the Adverse Childhood Events questionnaire discussed earlier in the report be used as a tool by educators in schools to help identify and understand children at risk for substance use and addiction and develop interventions to build resiliency among children and youth. This approach is currently being used by Alberta Family Wellness Initiative and is called the Brain Story.[145] Dr. Victoria Creighton also said that parents need tools and education to empower them to set limits with their children, allowing them to develop “the internal structure to say no to drugs or other things.”[146] She explained that this internal structure helps children mature. Finally, the Committee also heard from individuals with lived experience that community and recreational events for families in low-income neighbourhoods can help overcome a sense of disconnection and loneliness and create hope. As James Favel, Executive Director, Bear Clan Patrol Inc. stated to the Committee, “Amazing things can be accomplished by people with purpose, and we try to provide that purpose.”[147]

Harm Reduction

The Committee heard that scaling-up harm reduction measures is critical part of addressing the rising use of methamphetamine across Canada and its associated harms, despite concerns that may exist regarding these approaches. Witnesses identified two main types of harm reduction measures that need to be available: access to an uncontaminated supply of methamphetamines or other stimulants and broader access to supervised consumption sites. Witnesses also outlined possible approaches towards promoting the adoption of harm reduction measures in interested Indigenous communities.

Uncontaminated Supply of Methamphetamine

The Committee heard that individuals using methamphetamine who are not ready yet to seek treatment for addiction need access to the pharmaceutical grade version of the drug because of contamination of the drug supply in Canada. In her appearance before the Committee, Ms. Sarah Blyth, Executive Director, Overdose Prevention Society, emphasized the need for individuals who use stimulants such as methamphetamine to have access to an uncontaminated supply of these drugs because of the harms associated with obtaining these drugs on the black market.[148] She explained that methamphetamine purchased on the black market is often contaminated with other substances, including laundry detergent and pig de-wormer, as well as fentanyl which can lead to overdose and death among users. Ms. Karen Turner, Board Member, Alberta Addicts Who Educate and Advocate Responsibly similarly recommended that the federal government make available a prescription form of methamphetamine called Desoxyn®[149] through Health Canada’s Special Access Programme.[150]

During their informal meetings in Vancouver, the Committee learned that this approach is currently being pursued successfully at the Providence Crosstown Clinic in the Downtown East Side.[151] At the clinic, individuals with opioid dependence are prescribed pharmaceutical grade heroin under medical supervision and are provided services and supports to help stabilize them. However, Dr. Susan Burgess, Clinical Associate Professor, University of British Columbia, Vancouver Coastal Health explained to the Committee during her appearance that programs that offer pharmaceutical grade heroin may not be an effective approach for all patients.[152] She noted that some individuals participating in the program have continued to seek illicit fentanyl because of the higher potency of the drug. Similarly, an individual may also continue to seek out street-grade methamphetamine because of its potency even if they have access to an uncontaminated supply of the drug.[153] In addition, some individuals with lived experience expressed concerns during informal meetings with the Committee that offering pharmaceutical grade methamphetamine through a supervised program would only perpetuate drug use rather than provide treatment.

Supervised Consumption Sites

The Committee heard that supervised consumption sites are critical in responding to the harms associated with methamphetamine use as well as opioids and other drugs.[154] The Committee learned in its fact finding mission across the country that there are varying models and approaches to providing supervised consumption services depending upon community needs. In Calgary, the Committee visited the Safeworks Harm Reduction Program which is located in the Sheldon M. Chumir Health Centre. In meeting with representatives from the Safeworks Harm Reduction Program, the Committee learned that the program provides a range of health care services and supports to individuals using drugs that improve their health outcomes and help them transition towards recovery. For example, the Committee learned that during one day at the supervised consumption site in January 2019, staff were able to prevent four overdoses; provide testing for STIs to one individual; provide four housing referrals, five referrals to detoxification centres and one referral for opioid treatment; and intervene in a case of domestic violence.[155]

Representatives of the Safeworks Harm Reduction Program explained that locating the supervised consumption site within a health care setting was critical in its success, as it facilitates users’ access to other health care services located within the same building. Similarly, the Committee heard that for many individuals, supervised consumption sites may be their only contact with the health care system. As Mr. Donald MacPherson, Executive Director, Canadian Drug Policy Coalition articulated:

The establishment of supervised consumption service is a powerful message to people who use drugs that we care about them and want to engage people in health services, not back alleys. No one has died of an overdose death in a supervised setting in Canada, by the way.[156]

In Vancouver, the Committee had the opportunity to visit other types of supervised consumption sites, including Insite and the Overdose Prevention Society located in the Downtown Eastside of Vancouver. Both these organizations offer similar services to those offered in Calgary but are more embedded within the local community of individuals who use substances. The Committee learned that in addition to supervised consumption services, the Overdose Prevention Society offers both volunteer opportunities and paid employment to individuals using substances to help support them in their recovery.[157] The Committee heard from individuals who had recovered from drug use and addiction that access to these types of supervised consumption sites had given them a sense of community and kept them alive long enough to make the decision to recover.

To support the establishment of additional supervised consumption sites across Canada, the Committee heard that it is important to address community concerns regarding these sites by engaging communities in dialogue and establishing common goals related to reducing the harms of substance use.[158] The Committee also heard from the Calgary Police Service that it is important to open several smaller sites in different areas to reduce the number of users at one site at one time, which would reduce the potential for drug trafficking and other crime around the sites.[159]

The Committee also learned that it is important to provide supervised consumption sites in areas where they are accessible to individuals who use substances, as research has shown that they are unwilling to travel more than one kilometre to access harm reduction services.[160] One possible approach to address needs of users is the creation of mobile supervised consumption services. The Committee visited L’Anonyme, a community-based harm reduction organization in Montréal that uses a mobile trailer that travels to underserved areas in the evenings to provide supervised injection services.[161] The Committee learned that Vancouver Coastal Health is also considering developing a similar mobile service. Witnesses also recommended that services offered at supervised consumption sites be expanded to allow for inhalation so individuals can smoke drugs to reduce the harms associated with injecting drugs.[162] They also said there is a need for more drug-checking services, which are not currently offered at all supervised consumption sites.[163]

Harm Reduction in Indigenous Communities

“The establishment of supervised consumption service is a powerful message to people who use drugs that we care about them and want to engage people in health services, not back alleys. No one has died of an overdose death in a supervised setting in Canada, by the way.”

Mr. Donald MacPherson, Executive Director, Canadian Drug Policy Coalition

Dr. Esther Tailfeathers, Medical Lead, Population, Public Indigenous Health, Strategic Care Network explained to the Committee that many Indigenous communities currently pursue abstinence-based approaches towards substance use.[164] Consequently, they may not be supportive of harm reduction approaches and/or individuals in living in these communities may face stigma in accessing these services. However, she explained that the Blood Tribe in Lethbridge, Alberta had successfully adopted harm reduction approaches in response to the opioid crisis, including distributing naloxone kits, providing supervised injection services and providing suboxone. They are also in the process of establishing a supervised withdrawal site. She recommended that the federal government consider discussing harm reduction approaches with interested Indigenous communities and encourage them to work with local harm reduction agencies to provide help for Indigenous people both on and off reserve.[165] Finally, she recommended that there be venues for Indigenous communities to share promising approaches, such as the Blood Tribe’s supervised withdrawal site.[166]

The Committee also heard from Jenna Wirch and Dawn Lavand of the community-based organization 13 Moons Harm Reduction Initiative during its informal meetings in Winnipeg that there needs to be more culturally based harm-reduction initiatives for Indigenous youth.[167] The Committee learned that 13 Moons provides peer support to urban Indigenous youth who use drugs or are facing other obstacles to help them navigate programs and services, as well as provide safer drug consumption supplies.[168]

Treatment

Access to Withdrawal Management and Long-Term Residential Treatment Programs

Despite commitments made with provinces and territories through the Emergency Treatment Fund and other bilateral agreements, the Committee heard from all witnesses that there is an urgent need for federal, provincial and territorial governments to provide substantial additional funding to expand the availability of and provide timelier access to treatment services for substance use and addiction across the country. Though current numbers regarding the demand for services are unavailable, Suzy MacDonald, Assistant Deputy Minister, Opioid Response Team, Department of Health, explained that there were 220,000 people waiting to have access to addiction treatment services in Canada in 2014.[169] In addition, witnesses stressed that in the case of addiction, treatment services also need to be provided in a timely manner:

When someone who has an addiction makes the decision that they want to make a change in their life, it has to happen there. You can’t say to them, “I can have a treatment bed for you in three months” because then they’re back out on the street, and they’ve lost that need for change.[170]

Furthermore, the Committee heard that once individuals are able to access treatment they are also experiencing bottle necks in accessing different types of substance use and addiction treatment services. The Committee learned that treatment for substance use and addiction first involves accessing withdrawal management services so that individuals can safely stop using methamphetamines in a supportive environment.[171] They then move on to residential or non-residential treatment programming that provides behavioural counselling and mental health supports. However, while some individuals may be able to access withdrawal management services, the Committee heard from Dr. Peter Butt, Associate Professor, University of Saskatchewan that individuals then face long wait-times for residential treatment programs, which creates a significant risk of the individuals relapsing. [172]

The Committee heard from substance use and addiction experts that there is also a need to fund longer-term withdrawal management and treatment services and programs to better meet the needs of individuals experiencing methamphetamine addiction.[173] The Committee learned that there are currently no pharmacological treatments available to reduce cravings and withdrawal symptoms for methamphetamine as is the case with opioids, which makes it more difficult to treat than other addictions.[174] In addition, Dr. Fandrey from the Addictions Foundation of Manitoba explained that withdrawal symptoms from methamphetamine, including volatility, depression, extreme fatigue and cognitive deficits, can last up to two to three weeks, whereas withdrawal services may only be provided for shorter periods of time.[175] Furthermore, Dr. Peter Butt explained that residential treatment options need to be provided for longer periods for methamphetamine addiction, as recovery can take up to two years.[176] Current residential treatment programs for substance use and addiction tend to be offered for periods of 30 days only. Long-term residential treatment is also seen as the preferred option for individuals with an addiction to methamphetamine because of their psychosocial instability.[177] Witnesses therefore recommended that additional federal funding be directed towards the establishment of longer-term drug withdrawal and stabilization facilities and residential treatment programs for methamphetamine addiction.[178]

To address these bottle necks and gaps in services, the Committee heard that the Government of Manitoba had created Rapid Access to Addictions Medicine (RAAM) Clinics in the summer of 2018 to help vulnerable and hard-to-reach populations access services.[179] The Committee heard that these clinics are a promising initial approach to provide a treatment access point for these population groups. However, witnesses explained that the RAAM clinics mainly serve to refer individuals to withdrawal and residential treatment services that do not have the capacity to take in new clients.[180] In addition, the Committee heard that these clinics are not accessible as they are only open for two hours per day.[181]

For patients experiencing psychosis arising from their methamphetamine use, Dr. Susan Burgess, Clinical Associate Professor, University of British Columbia, Vancouver Coastal health said there is an urgent need to provide these individuals with psychiatric care to support their stabilization, including access to a psychiatric team and appropriate treatment. [182]

Support for Innovative Approaches to Meet Different Population Needs

The Committee also learned through its study that there is “no one size fits all” approach for providing treatments and services to individuals experiencing methamphetamine addiction. Consequently, funding needs to be made available to support different types of innovative approaches depending upon the needs of particular population groups. Witnesses from across the country highlighted various promising practices that have been effective in treating and supporting individuals recovering from methamphetamine use. An overview of these programs is provided below.

Morberg House/St. Boniface Street Links

Marion Willis, Founder and Executive Director, St. Boniface Street Links explained to the Committee that Morberg House is a 12-bed community-based residential facility that provides treatment and supports for men struggling with substance use and addiction, mental health issues and homelessness.[183] Residents are provided with a two-year case plan that includes linking them with physical health and mental health services and supports provided by the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority, and providing the residents with 12-step programs and counselling. While residents are required to go through detoxification before living at the house, they do not lose their spots if they relapse. During the Committee’s visit to Morberg House, residents explained that living there has been successful for them because it provides them with a sense of accountability and gives them a sense of home and belonging. Ms. Willis explained that Morberg House is funded through social assistance provided to the individuals, fundraising and community partnerships. She explained that because her residents are not considered chronically homeless, the program is unable to benefit from funding offered to address homelessness through the federal government’s new Reaching Home: Canada’s Homelessness Strategy.[184]

Indigenous Women’s Healing Centre

The Committee had the opportunity to visit the Indigenous Women’s Healing Centre in Winnipeg, which offers different types of residential facilities for Indigenous women and mothers who are healing from substance use and trauma.[185] The Indigenous Women’s Healing Centre offers North Star Lodge, which is a supportive home for women who are committed to recovering from substance use. They participate in programs that focus on building life skills, parenting, relapse prevention and healthy relationships. According to the organization’s Executive Director, Annetta Armstrong, women enter this home vulnerable and leave empowered. Once they have completed their time at the North Star Lodge, residents may move on to Memengwaa Place, also run by the Indigenous Women’s Health Centre, where they live independently and are able to have children in their care, while still having access to services and supports offered at the North Star Lodge. Residents explained that the services and supports offered at the North Star Lodge and having someone to talk to had prevented them from relapsing. They also appreciated that the residence is not located in an area where drugs are prevalent, which is often the case with other treatment facilities operated by the province. Ms. Armstrong said that she would like to provide fully integrated services by offering a “loving detox” in addition to the existing facilities.

Vancouver Native Health Society

In visiting the Vancouver Native Health Society, the Committee learned about how culturally-based substance use and addiction treatment services can be provided in a primary care setting.[186] Barry Seymour, Executive Director of the Vancouver Native Health Society, explained that the organization offers primary care, substance use treatment, psychiatric services, and support for skills development and counselling from Indigenous Elders to Indigenous people living in the Downtown East Side of Vancouver. The Committee learned that Elders play an important role in helping individuals heal from substance use because they provide them wisdom and knowledge to address substance use that is based upon a shared history, culture and identity.[187] According to Helena Flemming, Medical Clinic Manager, there is a need for a national funding model for urban Indigenous organizations providing health, social and cultural services. She explained that most federal and provincial funding for substance use and addiction services are provided on reserve or to Indigenous communities, but often residents end up leaving reserves and seeking treatments and services in urban environments. However, the funding for health and social services does not follow them. Dr. Sean Nolan, a psychiastrist working at the Vancouver Native Health Society, indicated that funding challenges had resulted in the organization in reducing the counselling services it is currently offering to patients.

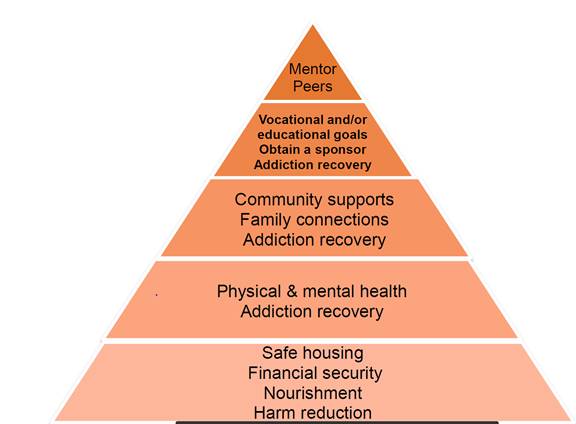

Housing and Social Supports

The Committee heard that better access to housing and social supports is also critical in supporting individuals in their recovery from methamphetamine addiction. Representatives from the Winnipeg Drug Treatment Court explained to the Committee that unless an individual’s basic needs in terms of housing and food security are met, they lack the stability and support necessary to access treatment and address the deeper issues underlying their substance use (see Figure 4).[188] According to the Calgary Homeless Foundation, these needs also provide the rationale for a “housing first” approach to addressing substance use in which individuals are provided permanent housing without the requirement for sobriety.[189] However, housing first models also do offer “wrap around” health and social supports to address substance use. Dr. Peter Butt, Associate Professor, College of Medicine, University of Saskatchewan explained that supportive housing can also fill the gap when individuals are waiting to access treatment after detoxification.[190] He also explained that there is a need for sober-living or therapeutic housing for individuals who have completed treatment. To address this gap in housing for individuals with substance use issues, witnesses recommended that there be better integration between health and housing policy across all levels of government.[191] They also recommended that the federal government create tax or other incentives for the creation of therapeutic housing and/or place legislative conditions on the Canada Social Transfers to the provinces and territories to address the social determinants of health that may lead to problematic drug use.[192]

Figure 4. Hierarchy of Needs in Addiction Recovery

Source: Government of Manitoba, “Winnipeg Drug Treatment Court: An Overview,” reference document provided to HESA, April 2019.

Criminal Justice Issues

The Committee heard from witnesses that individuals caught up in methamphetamine addiction often end up in the criminal justice system because they have no access to proper treatment. As James Favel, Executive Director, Bear Clan Patrol Inc. stated:

That addiction feeds the random violence, feeds the rampant poverty, property crime and it self-perpetuates: street, hospital, prison, repeat.[193]