RNNR Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

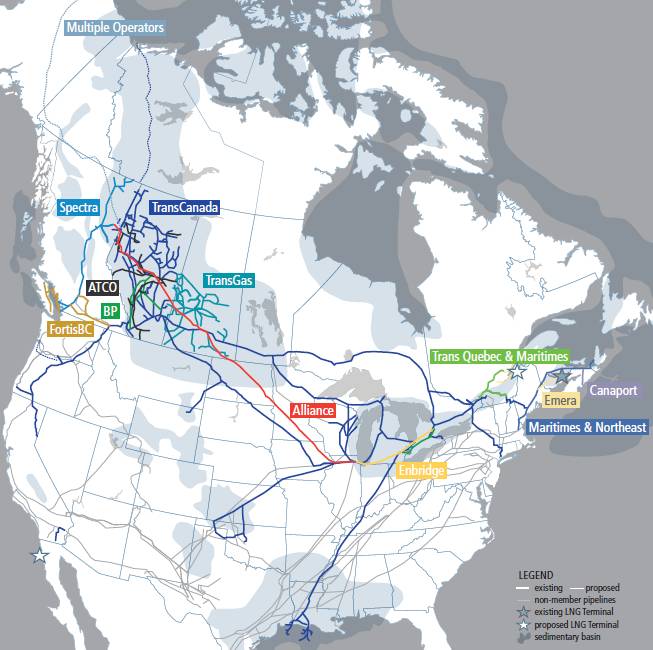

THE CURRENT AND FUTURE STATE OF OIL AND GAS PIPELINES AND REFINING CAPACITY IN CANADAINTRODUCTIONGlobal and domestic energy markets are undergoing changes that give rise to opportunities and challenges for Canada’s oil and gas and refining sectors. The overall gasoline and diesel demand in North America and other OECD countries is expected to decline over the next two to three decades.[1] On the other hand, the global demand for crude oil, especially in emerging economies, is projected to continue to increase “for the next 25 years and beyond”, which presents attractive export opportunities, considering Canada’s sizeable[2] oil reserves.[3] Furthermore, the discovery of large unconventional natural gas resources and the growing demand for alternatives to liquid fuels in Canada and the United States are expected to increase the role of natural gas in future North American markets.[4] Changes in the supply and demand of oil and gas affect Canada’s refining sector, which faces a number of challenges, including regional challenges, meriting special consideration. The emerging national and international trends in oil and gas markets bring about a number of concerns and opportunities regarding trade, infrastructure, employment, energy security, government regulation, and the environment, among others. In order to gain a better understanding of the various opportunities and challenges facing Canada’s oil and gas sectors, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Natural Resources conducted a study on the current and future state of oil and gas pipelines and refining capacity across Canada. Over the course of four meetings, the Committee heard from a number of witnesses from government, Aboriginal groups, academia, unions and the private sector. This report concludes the Committee’s study, and brings forward recommendations for consideration by the Government of Canada. OVERVIEWA. PipelinesNorth America’s oil and gas pipeline networks are closely integrated, particularly between Western Canada and the U.S. Midwest. In Eastern Canada, connections are mostly south-north, linking New England states to Quebec and Ontario through Portland, Maine (Figures 1 and 2). There are over 100,000 kilometres of pipelines in Canada, over 70%[5] of which are regulated by the National Energy Board (NEB). In the past five years, the value of energy transported over NEB-regulated pipelines to Canadian and export markets exceeded $100 billion annually, peaking at $127 billion in 2008, while the cost of transport through the same pipelines averaged less than $5 billion[6] annually. Energy exports by pipeline contribute to approximately one fifth of Canada’s total annual merchandise export revenues.[7] Figure 1: Liquid Pipelines in Canada and the United States

Source: Canadian Energy Pipeline Association, http://www.cepa.com/map/. Figure 2: Natural Gas Pipelines in Canada and the United States

Source: Canadian Energy Pipeline Association, http://www.cepa.com/map/. As Figure 3 demonstrates, pipelines serve a number of different purposes in the distribution of oil and gas. There are two general types of energy pipelines, the majority of which are buried underground:

Figure 3: Crude Oil (left) and Natural Gas (right) Delivery Networks

Source: Professor Hossam Gabbar, document presented to Committee, January 31, 2012. The NEB oversees pipeline regulation throughout the life cycle of a given pipeline. During the application phase, the NEB assesses whether the pipeline is in the public interest, and “whether the project can be built and operated safely and in a manner that protects people and the environment.” During the planning phase, companies must meet the NEB’s regulatory requirements and demonstrate “meaningful public involvement and consultation.” If a project gets approved, the NEB may also attach any conditions deemed to be in the public interest. The NEB continues to monitor and verify compliance with regulatory requirements throughout the construction and operation phases of a given project. Finally, if a pipeline is to be abandoned, the NEB is responsible for ensuring that the company’s abandonment plan can be conducted “safely while protecting the environment at the time of abandonment and beyond.”[12] Pipelines extending over 40 kilometres require a public hearing under section 52 of the National Energy Board Act. According to Gaétan Caron, Chair and CEO of the NEB, the overall length of the review process is “based on an independent decision of the panel hearing the case.”[13] According to Professor Hossam Gabbar, “pipelines are the safest[14] and most efficient means of transporting large quantities of crude oil and natural gas over land.”[15] Similarly, Mark Corey, Assistant Deputy Minister, Energy Sector, Natural Resources Canada (NRCan), stated that pipelines are the “safest and cheapest way to transport large quantities of oil over long distances [...]”.[16] Furthermore, Mr. Caron told the Committee that “studies continue to confirm that pipelines operate more safely than any other mode of transportation of hydrocarbons.”[17] Possible pipeline risks include leaks, ageing, human error and corrosion, which varies according to the impact of different chemical properties on a given pipeline.[18] The NEB recently reported that pipeline worker serious injury rates are low and are continuing to drop, and that the environmental impacts of leaks have been “localized and fully remediated in compliance with [NEB] requirements, guided by international best practices.”[19] Between 2000 and 2011, petroleum spills amounted to approximately 3,715 barrels[20] per year. There were two incidents in 2009, eight incidents in 2010, and, by September, four incidents had occurred in 2011.[21] Pipeline companies are held accountable for the safety of their facilities and the protection of the environment in which they operate, throughout the life cycle of a given pipeline. They are required to anticipate, prevent, mitigate and manage incidents of any size or duration. In the case of a serious incident, the NEB oversees the regulated company's “immediate and ongoing response and cleanup,” and requires that “all reasonable actions be taken to protect employees, the public, and the environment.” According to Gaétan Caron, in areas where the NEB finds that safety can be improved, it takes the necessary actions to rectify the situation. The NEB has the authority to “shut down the pipeline company's operation. Failures or serious injuries must be reported to the board by law. The board requires companies to conduct their own investigations and submit their results. In serious cases [the NEB] will conduct [its] own investigation.”[22] Pipeline construction generates a wide range of direct and indirect employment opportunities within the energy sector, including construction jobs to build the infrastructure necessary to support the consequential growth within the oil and gas sector (e.g., office towers). According to Christopher Smillie, Senior Advisor, Government Relations, Building and Construction Trades Department, at the Canadian Office of the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO), even though direct pipeline construction jobs last, on average, three seasons, “the vast bulk of jobs created last for 50 years or more.” For instance, the AFL-CIO represents about 80,000 to 90,000 skilled trade workers in Alberta who “in one way or another [...] work in the energy sector.” Mr. Smillie told the Committee that pipelines are “more than a connection for products. The pipeline links together jobs from one end of the production chain to the other end of that chain.”[23] According to John Quinn, General Manager, Integration and Planning, Refining and Marketing, Suncor Energy Inc., there is a shortage of skilled jobs in the oil and gas industry. The biggest challenge facing Suncor’s business expansion plans is “the need for thousands of skilled jobs, in Alberta in particular, but they resonate across the country for suppliers of goods and services to that construction effort and to that ongoing production effort as we go forward. There is no shortage in the requirement for skilled jobs in this country going forward.”[24] B. RefiningRefineries are used to produce a wide range of products, including gasoline, diesel oil, lubricating oil, and naphtha (used for the production of certain chemicals). Figure 4 presents a simplified illustration of a refining plant. By heating crude oil and injecting it into a distillation tower, different products are produced at different temperatures.[25] According to Peter Boag, President of the Canadian Petroleum Products Institute (CPPI), petroleum product refineries are not the same as bitumen upgraders. Refineries are more complex facilities, built and configured to process crude oil — “from heavy to light, from sour to sweet and now synthetic, into products such as gasoline, diesel, aviation fuel and home heating oil.” On the other hand, bitumen upgraders are built and configured to process bitumen feed — which is unsuited for processing in most product refineries — into synthetic crude suitable as a product refinery feedstock. An upgrader and a refinery can be integrated into a single facility.[26] Figure 4: Simplified Oil Production Chain from Refining

Source: Professor Hossam Gabbar, document submitted to the Committee on January 31, 2012 There are 19 refineries across Canada, with an aggregate production capacity of approximately two million barrels per day.[27] Of the 19 refineries, 15 produce the full range of petroleum products. Refineries in Western Canada use domestic crude oil delivered via pipeline, while in Eastern and Atlantic Canadian refineries, 15% of the oil comes from domestic offshore production and 85% is imported via tanker into Halifax, Saint John or Come By Chance.[28] In Quebec, crude oil is imported via small tankers into Lévis, or via larger tankers into Portland, Maine, and then delivered to Montréal by pipeline. Finally, in Ontario, refineries mainly use domestic crude oil, in addition to small volumes of imported crude, generally delivered through the Portland-Montréal Pipeline and the Enbridge Line 9 Pipeline.[29] As Figure 5 demonstrates, every Canadian province, except for Manitoba and Prince Edward Island, has at least one refinery. Figure 5: Canadian Refineries and Refining Capacity[30]

Source: Canadian Petroleum Products Institute, document presented to Committee, January 31, 2012. In addition to the 19 refineries in Canada, there are seven upgraders in Alberta that process 100% bitumen feed — unlike petroleum product refineries, which are built and configured to process crude oil. According to Peter Boag, “some upgraders produce limited amounts of finished products, generally diesel.”[31] Mark Corey told the Committee that Alberta’s objective is to upgrade two thirds of its crude oil production by 2020, which would require four additional upgraders at the cost of approximately $3 billion each.[32] In 2010, Canada produced 1.5 million barrels of bitumen per day, of which 0.8 million bb/d, or 53%, was upgraded.[33] About 90% to 95% of Canadian refinery output is fuel products, while 5% to 10% is petrochemical feedstock.[34] As a net exporter of refined petroleum products, Canada exports approximately 20% (or 400,000 bpd) of its refining output, mainly from Quebec and Atlantic Canada to the Northeastern United States.[35] According to Peter Boag, “the bottom line is that at the end of the day, [Canada is] a net exporter of refined products to about 20% of our capacity in a very competitive North American market. We think that's a pretty positive story for Canada.”[36] In 2009, Canada’s refining sector contributed $2.5 billion to the Canadian economy, and employed about 17,500 “highly educated and well-paid” refinery workers.[37] A report by the Conference Board of Canada indicates that refinery workers earn approximately 50% more than workers in Canada’s overall manufacturing sector.[38] According to Christopher Smillie, at refineries “there are jobs sustaining construction, operations, and maintenance. Those jobs are there for 50 years. Pipelines link those jobs together. If there's no pipeline to markets, those other high-paying, high-skilled, and challenging jobs don't exist.”[39] The number of refining plants in North America dropped from over 360 in the 1970s and 1980s to less than 140 today. According to Michael Ervin, Vice-President and Director of Consulting Services at MJ Ervin and Associates, the closure of about 200 refineries since 1970 was a result of excess refining capacity and poor returns on capital within North America’s refining sector. Furthermore, the progression of fuel quality mandates (e.g., reductions in lead, benzene, sulphur, etc.) presented challenges to the industry, particularly smaller and less efficient refineries that could not justify the large investments needed to comply with the new mandates.[40] By the mid-1990s, the steady increase in petroleum demand in North America caused the utilization rates of refining plants to exceed 90%, which is optimal in terms of profitability. As a consequence, many refineries attracted high capital investment, and underwent expansion in order to meet the growing demand for petroleum products.[41] Canadian refining capacity has consistently responded to the market conditions of supply and demand. The expansion of Canadian refineries has, on average, increased Canada’s refining capacity, despite the decline in the number of refineries over the past five decades (Figures 6 and 7). In 1960, there were 44 refineries producing about 945,000 b/d across the country, compared to 19 refineries today and a production rate of approximately 1,886,000 b/d in 2011.[42] (Of the 19 Canadian refineries, 15 produce the full range of petroleum products.) Given the fact that Canada’s refining industry is not operating at full capacity, and that petroleum fuel demand has likely peaked in North America and other OECD countries[43] (and will likely continue to decline in upcoming years[44]), there is currently no economic basis for building new refineries in Canada. Figure 6: Number of Canadian Refineries, 1960-2011

Source: Natural Resources Canada, document presented to Committee, January 31, 2012. Figure 7: Canadian Refining Capacity, 1960-2011

Source: Natural Resources Canada, document presented to Committee, January 31, 2012. EMERGING MARKET TRENDS: OPPORTUNITIES AND CHALLENGESA. Crude OilThe growing global demand for crude oil, particularly in emerging economies, is expected to increase the export opportunities for Canada’s upstream oil sector.[45] According to Professor Jack Mintz, considering that Canadian exports are largely dependent on the United States, diversifying crude export markets would improve Canada’s leverage as an exporter, particularly with respect to negotiations with the United States — a large energy market with strong negotiating powers.[46] Upgrades to pipeline infrastructure could achieve two main goals: 1) facilitate the export potentials of Canadian crude oil to emerging markets overseas, and 2) improve the efficiency of export markets within North America. The two most commonly used pricing standards for crude oil are the West Texas Intermediate (WTI), based on prices in Cushing, Oklahoma, and the Brent (considered the world price), based on prices in the North Sea. In recent years, the Brent pricing has been generally higher than the WTI pricing, by as much as $25 per barrel at one point (on January 31, 2012, the differential was $13 per barrel; and recently, it dropped to $9 per barrel). According to Mark Corey, once the oil is delivered to tidewater, “the two price levels come more into line.”[47] In other words, in current North American crude oil markets, waterborne crude has a higher value than landlocked crude. Professor Michal Moore told the Committee that a number of pipeline networks in North America rely on additional support from rail, barge or truck in order to deliver crude oil to refining facilities or tidewater ports, which adds to the overall cost of oil distribution. For example, he stated that “in the Houston market, in moving down to [the] gulf coast market, we give away about $10 a barrel in potential headroom to producers.” Similarly, “in the California market, where the reserves of heavy crude are declining in the California basins, we give away even more, up to about $13 a barrel, depending on conditions.”[48] Brenda Kenny, President and Chief Executive Officer of the Canadian Energy Pipeline Association (CEPA), stated the following: “[...] currently there are some market distortions in North America. In total, depending on the numbers, that can cost Canada anywhere from $14 billion to $18 billion a year. That is in addition to lost tax revenues, fewer dollars for reinvestment in Canada, and lower returns to all shareholders, many of whom are pensioners.”[49] According to Professor Jack Mintz, it is important for Canada “not to be too reliant on only one market, and there is some value to diversification as a result.” [50] Similarly, Mark Corey told the Committee that “strategically it would be wise of [Canada...] to diversify beyond the U.S. market to make sure we're getting the best price possible for our crude.”[51] Professor Michal Moore stated that the price differential that can be captured by improving the pricing of Canadian crude oil exports “represents several hundred billion dollars over a 20- to 30-year period that's available to government.” He stated the following: “[The main point] is being able to reach what amounts to a tidewater access pricing point. It’s important to differentiate between where our products actually go versus where they're priced. Right now, some of the knock on the Keystone pipeline, which is coming from various sectors in the U.S., suggests that all we're trying to do is export to foreign markets [...]. Where we have an advantage is in getting into the U.S. gulf coast, where our products can be processed and then transformed into gasoline and other distillates, and reaching out to a U.S. market. When we can do that, we get a higher world price, and that translates directly back into tax revenues and royalties that are significant, literally, for every province in Canada.”[52] Furthermore, Professor Mintz stated that there are both economic and political gains to shipping either to California or to Asia: “It does potentially increase the GDP in Canada, as I recall, by about a percentage point over the next number of years, if we do export to either Asia or California, partly because we can achieve some better pricing for our product. That's assuming that we also deal with the Cushing inventory problem, where oil has to be sent at a high cost down to the gulf coast. It's more pipelines set up, and we do see an elimination of differential between the international price and the West Texas Intermediate price, which will be a big gain for Canada as well.”[53] The choice of how and where to export crude oil, according to Professor Mintz, “comes down to [...] the economic advantages of different alternatives,” adding that “there are very significant advantages of still selling to the United States, particularly to the gulf area.” He emphasized the role of transportation costs in the economics of crude oil exports.[54] Even though some oil pipelines have increased their capacity in recent years, the overall Canadian export pipeline capacity is tight, with “little flexibility in the system,” according to the NEB.[55] The following pipeline proposals could improve the access of crude oil from Western Canada’s sedimentary basin to international markets:

Some of the opposition to the pipeline proposals involves environmental groups in Canada and the United States. Vivian Krause suggests that some of these groups have received millions of dollars from U.S.-based foundations, “specifically for campaigns targeting the oil and gas industry in Canada.”[62] There has been some support and opposition to oil and gas pipeline proposals from different Aboriginal groups. According to Michael Ervin, while the Keystone XL and Northern Gateway proposals are important to ensure continued growth in Canada’s upstream industry, particularly the oil sands, they would reduce the competitiveness of Canadian refineries that currently process crude oil from Western Canada.[63] Furthermore, Joseph Gargiso, Administrative Vice-President of Communications at the Energy and Paperworkers Union of Canada, told the Committee (with reference to estimates by economist Michael McCracken) that “for every 400,000 barrels of raw bitumen exported out of the country for upgrading and refining, 18,000 [well-paid] jobs in Canada will be lost [...],” not including jobs related to downstream activities, such as manufacturing.[64] Joseph Gargiso is of the view that Canada’s energy security could be compromised by the exportation of large quantities of raw Canadian crude oil for processing abroad. Furthermore, Professor Larry Hughes expressed concern regarding the possible impacts of foreign supply disruptions on the availability and affordability of oil products, particularly in the Atlantic Provinces.[65] Atlantic Canada and Quebec import about 83% and 86.5% respectively of their oil from foreign countries, some of which have either peaked (e.g., the United Kingdom, Norway, Russia and Venezuela) or are located in politically volatile regions (e.g., Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Nigeria and Angola).[66] According to Mr. Gargiso, Canada could be vulnerable to oil supply disruptions from the Middle East “through its dependence on refined products sourced from [European] countries themselves dependent on the Middle East.” If the current excess of European gasoline production withers, Europe’s gasoline exports to Canada could be reduced.[67] On the other hand, Mr. Ervin told the Committee that North America has sufficient safeguards in the case of an energy shortage, such as the U.S. strategic oil reserve, which could supply the United States for several months. “In a North American context and given the NAFTA provisions, we have a degree of security by that means alone.”[68] Furthermore, John Quinn affirmed that Canada has a secure supply of energy.[69] To address the potential energy security concerns of increasing Canada’s reliance on foreign oil, some witnesses supported the idea of reversing Enbridge’s Line 9[70] pipeline between Sarnia and Montréal. The reversal would make crude oil from Canada’s western sedimentary basin available to Eastern Canada (and possibly Atlantic Canada), and could potentially allow western crude oil to serve New England, through Portland, Maine.[71] Professor Larry Hughes told the Committee that crude oil could be delivered from Montréal to Atlantic Canada through the Montréal-Portland pipeline (which would also have to be reversed) and, subsequently, by tanker from Portland to Atlantic Canada's three refineries. Alternatively, it could be delivered more expensively by tanker from Montréal to Atlantic Canada directly.[72] According to Joseph Gargiso, the reversal of Enbridge’s Line 9 could reduce Eastern Canada's reliance on foreign oil by 20% to 25%.[73] Furthermore, John Quinn, General Manager, Integration and Planning, Refining and Marketing, Suncor Energy Inc., stated that the reversal could “foster possible investments at [Suncor’s] Montréal refinery to allow it to more fully adapt to [western] crudes [...] and would help secure Montréal refinery’s long-term flexibility, [...] performance and [...] viability.”[74] Mr. Quinn added that Suncor’s refinery is already capable of processing some western crude oil, although there is “no pipeline connection to allow that to happen at a cost-effective level.”[75] Recommendation 1 In order to maximize the competitiveness of Canada’s crude oil production, the Committee recommends that the Government of Canada implement a streamlined regulatory process, including set timelines that ensure a fair, independent and science-based regulatory process, while at the same time considering the viewpoints of local communities and industry, and respecting the duty to consult Aboriginal groups. The streamlined regulatory process should be harmonized between the provincial, territorial and federal governments, should not reduce the current public access to the review process, and should provide exemplary environmental stewardship. Recommendation 2 Given the testimony regarding Enbridge’s Line 9, the Committee recommends that the National Energy Board’s function be re-examined and that the NEB conduct an internal review of its approval processes to ensure that pipeline decisions respecting existing infrastructure be done in a timely manner. These reviews are to be transparent and public, and are to include a wide range of stakeholders. Recommendation 3 The Committee recommends that the Government of Canada recognize the importance of Canada’s pipeline system, as evidence shows it is the safest and most efficient way to transport oil, gas and other hydrocarbons. B. Refined Petroleum ProductsThe prospects of Canada’s refining sector appear uncertain, according to some Committee witnesses, particularly considering the recent and projected declines in North America’s demand for gasoline, which constitutes about 40% of the continental production of petroleum products.[76] Since the 2008 economic recession, Canadian refineries have had a relatively high surplus capacity, with utilization rates averaging 80% in Ontario and Western Canada and 84% in Atlantic Canada and Quebec.[77] (To ensure profitability, refineries need to operate with a utilization rate of 90% or over.[78]) Figure 8 outlines Canada’s average refinery capacity, production and utilization rates between 2001 and 2011. Figure 8: Canada’s Refinery Capacity, Production and Utilization Rates, 2001-2011

Source: Canadian Petroleum Products Institute, document presented to Committee, January 31, 2012. Canada’s refining sector faces the following economic challenges, according to some Committee witnesses:

The production and domestic sales of refined petroleum products vary in different regions of Canada (Figure 9), leading to different challenges with regards to changes within the refining sector. According to Keith Newman, Director of Research, Energy and Paperworkers Union of Canada, recent refinery closures have led Eastern Canada (i.e., Ontario and Quebec) to a situation of dependency on foreign suppliers of petroleum products, particularly gasoline, thereby increasing the region’s vulnerability in the case of an unexpected foreign or domestic supply disruption. The shutdown of Petro-Canada’s Oakville refinery in 2005 has resulted in an approximated 20% shortfall of refined products in Ontario (the equivalent to five million cubic metres annually), leading that province to rely on “surplus production in Quebec and foreign countries.”[89] In 2007, southern Ontario was subjected to gasoline shortages for “several weeks” as a result of a fire at Imperial Oil’s Nanticoke refinery near Hamilton. During the shortage, 135 gas stations were closed[90] and gasoline prices rose by 10¢ to 15¢ a litre. “It was widely understood [that] the tight supply in the province was the main cause of the shortage,” according to Mr. Newman.[91] Subsequently, the closure of Shell Canada’s Montréal refinery in 2010 made Quebec “barely self-sufficient,” leading both Quebec and Ontario to a situation of dependency on foreign suppliers.[92] In the summer of 2011, the Greater Toronto Area, Sarnia, and London experienced shortages due to routine maintenance at a Shell refinery in Sarnia that took longer than expected.[93] However, Michael Ervin said it is speculation that building more Canadian refineries would lower the price of wholesale and retail fuels for Canadian consumers. He said it is important to understand that “Canadian refineries are really just part of a North American capacity pool, and lower wholesale prices in Canada brought about by more capacity would quickly attract U.S wholesale buyers, thus negating any hopes of sustained lower prices in Canada.”[94] Figure 9: Refining Production and Domestic Sales (thousand b/d)

Source: Canadian Petroleum Products Institute, document presented to Committee, January 31, 2012. Recent refinery closures have triggered job losses, particularly in Ontario and Quebec. In 2005, the shutdown of Petro-Canada’s Oakville refinery resulted in the loss of 350 direct jobs, and “thousands of additional jobs [...] by contractors and suppliers [...]”[95] Furthermore, Keith Newman told the Committee that the 2010 shutdown of Shell Canada’s Montréal refinery resulted in a minimum loss of 2,000 jobs, according to estimates from the Institut de la statistique du Québec.[96] Based on estimates by the Conference Board of Canada,[97] the Communications, Energy and Paperworkers Union of Canada calculated that, over a five-year period, the shutdown of the Oakville and Montréal refineries resulted in a loss of approximately 25,000 person years of direct, indirect and induced jobs, in addition to estimated losses of $2.6 billion in GDP and $330 million in federal and provincial taxes.[98] Considering the various economic and social challenges outlined above, the prospects of Canada’s refining industry remain uncertain. Some industry representatives appear sceptical of the feasibility of further expansions of Canadian refineries. For example, John Quinn stated that even though Suncor Energy will remain committed to its refinery plants “as long as they are competitive and profitable,” North America’s current surplus of refining capacity and declining demand for petroleum products “does not easily support the expansion of domestic refining capacity.”[99] According to Peter Boag, “the size of Canada’s petroleum products refining [...] footprint will be market driven, and the sum of many individual business decisions will be influenced by a myriad of factors including commercial strategies, crude availability and cost, logistics and labour issues, product demand and market access, and the Canadian policy/regulatory environment.” Mr. Boag emphasized the importance of “[letting] competition work,” adding that “Canadians enjoy some of the lowest prices of gasoline in the world and [...] operate on a competitive basis. We think the competitive system works well.” On the other hand, Mr. Boag expressed the need, under the right economic conditions, for continued investment in existing refining infrastructure (e.g., to improve efficiency or environmental performance) in order to maintain the competitiveness of Canada’s refining sector.[100] C. Natural GasFuel demand in North America is expected to shift towards alternatives to liquid fuels, including natural gas.[101] Furthermore, the sizeable unconventional natural gas resources in North America are likely to play a critical role in future energy markets.[102] According to the NEB, there have been a number of changes to the throughputs on natural gas pipelines in recent years (Figure 10):[103]

Figure 10: Average Throughputs of Major Natural Gas Pipelines

Source: National Energy Board, The current and future state of oil and gas pipelines and refining capacity in Canada, Follow-up document submitted to the Committee on February 16, 2012. Atlantic Canada faces challenges regarding the availability and affordability of natural gas, according to Professor Larry Hughes. Approximately 90% of Atlantic Canada’s natural gas, most of which is from Nova Scotia, is exported to New England, leading industrial, residential, commercial and institutional sectors to rely on oil products, electricity, and biomass for process heat and space heating.[104] As previously mentioned, 83% of Atlantic Canadian oil is sourced from foreign countries that have either peaked or are located in politically volatile regions, which arguably compromises the region’s energy security.[105] Furthermore, according to Mr. Hughes, the region’s average percentage of household income spent on energy is close to energy poverty (i.e., 8% to 10%), with Prince Edward Island at 6% and the rest of Atlantic Provinces exceeding 5%.[106] Professor Jack Mintz is of the view that natural gas could be an important alternative fuel for Atlantic Canada’s future, particularly in the utility, heating and some parts of the transportation sectors. He told the Committee that the shale gas developments in New Brunswick could have a significant impact on the development of energy markets in the Atlantic region.[107] The Committee heard from witnesses regarding the prospects of the Mackenzie Valley Natural Gas Pipeline project — an example of a project that could improve Canada’s preparedness for the anticipated growth in North America’s natural gas markets.[108] The proposal is to transfer natural gas from the Mackenzie Delta (Northwest Territories) to natural gas markets in the south with an initial capacity of 1.2 billion cubic feet a day — which could be expanded to 1.8 billion cubic feet a day by adding compressor stations along the route. According to Robert Reid, President of the Mackenzie Valley Aboriginal Pipeline LP, the Mackenzie Valley project would provide “a positive GDP impact of over $100 billion, with royalty and tax revenue of over $10 billion to federal, provincial, and territorial governments [...]” In terms of employment, the project’s construction phase is projected to create over 7,000 jobs in the Northwest Territories (or approximately 30,000 person-years) and over 140,000 across Canada (or approximately 200,000 person-years). Furthermore, as part of the access and benefits agreements, Aboriginal contractors are guaranteed $1 billion in set-aside work along the pipeline. According to a memorandum of understanding concluded in June 2011 between Aboriginal groups and Imperial Oil, ConocoPhillips, Shell and Exxon Mobil, Aboriginal groups have a “one-third ownership position in the Mackenzie Valley pipeline”, which represents “a good model for harmonious Aboriginal participation in our major projects”. Mr. Reid also told the Committee that the Mackenzie gas project could lead to a 600-megatonne reduction in Canada’s greenhouse gas emissions, if used to displace coal and oil in the power generation market, which is forecast to grow by 40% by 2020.[109] According to Mr. Reid, the Mackenzie Valley Pipeline project is not feasible based on current gas prices. On the other hand, North America’s growing demand for natural gas is expected to improve the project’s economic viability by 2020. The Mackenzie Valley Aboriginal Pipeline LP is currently negotiating a fiscal arrangement with the Government of Canada to reduce the capital cost of the project.[110] Professor Michal Moore told the Committee that a better understanding of the scope and structure of emerging natural gas markets in North America and better knowledge of the necessary infrastructure to support these markets would improve the prospects of Canada’s energy future.[111] Professor Moore also stated that a growing natural gas market would likely support an electric market that requires specific hardware and infrastructure.[112] MOVING FORWARDA number of witnesses suggested that the government consider an energy strategy to address any economic, social, infrastructural, regulatory, environmental or other issues facing Canada’s energy sector. For example:

The federal, provincial and territorial energy ministers are collaborating on a number of issues. For example, in July 2011, Ministers of Energy from across Canada agreed on the following priorities with regards to the energy sector: regulatory reform; energy efficiency; energy information and awareness; energy markets and international trade; smart grid technology; and electricity reliability.[119] Based on the evidence outlined in this report, the Committee makes the following recommendations: Recommendation 4 The Committee recommends that the Government of Canada commit to developing and diversifying markets for Canadian energy products. Recommendation 5 Given the consequences of the National Energy Program, the Committee recommends that the Government of Canada continue its markets-driven approach to the refining sector, while recognizing the refining sector operates as a North American market. Recommendation 6 In order to maximize the competitiveness of Canada’s energy industries, the Committee recommends that the Government of Canada work with the provinces and territories to ensure an optimal investment climate, through measures such as tax reduction and regulatory reform. Recommendation 7 The Committee recommends, with regards to an energy strategy, that the Government of Canada coordinate with the provinces and territories, keeping in mind provincial and territorial jurisdictional responsibilities. Recommendation 8 Given the large amount of money transferred to the provinces for post-secondary education and training, and the skills and human resources gap facing the energy sector, the Committee recommends that the Government of Canada consider the skilled labour shortage facing the energy industry, and the need for labour to move effectively both across the country and throughout the North American market. Recommendation 9 Given the significant labour shortages forecasted in many regions of Canada and particularly in the energy sector, the Committee recommends that the Government of Canada review its immigration programs and change the point system to better align the skills of those who are able to immigrate to Canada with the labour market needs of the country, and that the Government of Canada consider providing a larger role for employers in the immigration system. [1] John Quinn, General Manager, Integration and Planning, Refining and Marketing, Suncor Energy Inc., Evidence, February 2, 2012. [2] According to Natural Resources Canada (Evidence, January 31, 2012), Canada’s crude oil reserves are estimated to amount to about 174 billion barrels (including 170 billion barrels in the oil sands), and could grow to 300 billion barrels, as extraction technology advances and becomes economically viable. [3] Peter Boag, President, Canadian Petroleum Products Institute, Evidence, January 31, 2012. [4] Professor Michal Moore, School of Public Policy and ISEE Core Faculty, University of Calgary, As an Individual, Evidence, February 7, 2012. [5] The remaining 30% fall within provincial jurisdiction. [6] According to Brenda Kenny (follow-up correspondence with the Committee, March 5, 2012), pipelines are capital-intensive projects that require large initial outlays (often billions of dollars). The return on investment of a pipeline could take up to 30 years. The $5 billion transport cost includes: depreciation costs, return on equity investment, annual cost of debt payments, and annual operating and maintenance costs (e.g., fuel, safety maintenance, inspections, taxes, etc.). All transport costs and associated tolls and tariffs are “normally approved by the appropriate regulators (NEB or provincial regulator), although the specific method of regulation can vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction.” [7] Canadian Energy Pipeline Association, document presented to the Committee, February 7, 2012. [8] Professor Hossam Gabbar, University of Ontario Institute of Technology, As an individual, document presented to Committee, January 31, 2012. [9] Ibid. [10] Brenda Kenny, President and Chief Executive Officer, Canadian Energy Pipeline Association, follow-up correspondence with the Committee, March 5, 2012, [11] Professor Hossam Gabbar, University of Ontario Institute of Technology, As an individual, document presented to Committee, January 31, 2012. [12] Gaétan Caron, Chair and CEO, National Energy Board, Evidence, February 9, 2012. [13] Ibid. [14] Professor Gabbar defined safety as “freedom from unacceptable risk.” [15] Professor Hossam Gabbar, University of Ontario Institute of Technology, As an individual, document presented to Committee, January 31, 2012. [16] Mark Corey, Assistant Deputy Minister, Energy Sector, Department of Natural Resources, Evidence, January 31, 2012. [17] Gaétan Caron, Chair and CEO, National Energy Board, Evidence, February 9, 2012. [18] Professor Hossam Gabbar, University of Ontario Institute of Technology, As an individual, document presented to Committee, January 31, 2012. [19] Gaétan Caron, Chair and CEO, National Energy Board, Evidence, February 9, 2012. [20] One barrel of oil is equal to 158.987 litres. [21] Mark Corey, Assistant Deputy Minister, Energy Sector, Department of Natural Resources, Evidence, January 31, 2011. [22] Gaétan Caron, Chair and CEO, National Energy Board, Evidence, February 9, 2012. [23] Christopher Smillie, Senior Advisor, Government Relations, Building and Construction Trades Department, Canadian office of the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO), Evidence, February 7, 2012. [24] John Quinn, General Manager, Integration and Planning, Refining and Marketing, Suncor Energy Inc., Evidence, February 2, 2012. [25] Professor Hossam Gabbar, University of Ontario Institute of Technology, As an individual, document presented to Committee, January 31, 2012. [26] Peter Boag, President, Canadian Petroleum Products Institute, Evidence, January 31, 2012. [27] Canadian Petroleum Products Institute, document presented to Committee, January 31, 2012. [28] Natural Resources Canada, document presented to Committee, January 31, 2012. [29] Ibid. [30] The refineries depicted in the map are located in the following cities (east to west): Come By Chance, NL (North Atlantic Refining); Dartmouth, NS (Imperial Oil); Saint John, NB (Irving Oil); Lévis, QC (Ultramar); Montréal, QC (Suncor); Mississauga, ON (Suncor); Nanticoke, ON (Imperial Oil); Sarnia, ON (Imperial Oil, Shell, Suncor and Nova); Regina, SK (Consumers’ Co-op); Moose Jaw, SK (Moose Jaw Refining); Lloydminster. AB (Husky); Scotford, AB (Shell); Edmonton, AB (Suncor and Imperial Oil); Prince George, BC (Husky); Burnaby, BC (Chevron). [31] Peter Boag, President, Canadian Petroleum Products Institute, Evidence, January 31, 2012. [32] Mark Corey, Assistant Deputy Minister, Energy Sector, Department of Natural Resources, Evidence, January 31, 2011. [33] Natural Resources Canada, document submitted to the Committee, February 24, 2012. [34] Mark Corey, Assistant Deputy Minister, Energy Sector, Department of Natural Resources, Evidence, January 31, 2012. [35] Canadian Petroleum Products Institute, document presented to Committee, January 31, 2012. [36] Peter Boag, President, Canadian Petroleum Products Institute, Evidence, January 31, 2012. [37] Mark Corey, Assistant Deputy Minister, Energy Sector, Department of Natural Resources, Evidence, January 31, 2012. [38] John Quinn, General Manager, Integration and Planning, Refining and Marketing, Suncor Energy Inc., Evidence, February 2, 2012. [39] Christopher Smillie, Senior Advisor, Government Relations, Building and Construction Trades Department, Canadian office of the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO), Evidence, February 7, 2012. [40] Michael Ervin, Vice-President, Director of Consulting Services, MJ Ervin and Associates, The Kent Group, Evidence, February 2, 2012. [41] Ibid. [42] Natural Resources Canada, document presented to Committee, January 31, 2012. [43] Mark Corey, Assistant Deputy Minister, Energy Sector, Department of Natural Resources, Evidence, January 31, 2012. [44] Michael Ervin, Vice-President, Director of Consulting Services, MJ Ervin and Associates, The Kent Group, Evidence, February 2, 2012. [45] Peter Boag, President, Canadian Petroleum Products Institute, Evidence, January 31, 2012. [46] Professor Jack Mintz, Palmer Chair in Public Policy, School of Public Policy, University of Calgary, As an Individual, Evidence, February 7, 2012. [47] Mark Corey, Assistant Deputy Minister, Energy Sector, Department of Natural Resources, Evidence, January 31, 2012. [48] Professor Michal Moore, School of Public Policy and ISEE Core Faculty, University of Calgary, As an Individual, Evidence, February 7, 2012. [49] Brenda Kenny, President and Chief Executive Officer, Canadian Energy Pipeline Association, Evidence, February 7, 2012. [50] Professor Jack Mintz, Palmer Chair in Public Policy, School of Public Policy, University of Calgary, As an Individual, Evidence, February 7, 2012. [51] Mark Corey, Assistant Deputy Minister, Energy Sector, Department of Natural Resources, Evidence, January 31, 2012. [52] Professor Michal Moore, School of Public Policy and ISEE Core Faculty, University of Calgary, As an Individual, Evidence, February 7, 2012. [53] Professor Jack Mintz, Palmer Chair in Public Policy, School of Public Policy, University of Calgary, As an Individual, Evidence, February 7, 2012. [54] Ibid. [55] National Energy Board, The current and future state of oil and gas pipelines and refining capacity in Canada, Follow-up document submitted to the Committee on February 16, 2012. [56] Professor Jack Mintz, Palmer Chair in Public Policy, School of Public Policy, University of Calgary, As an Individual, Evidence, February 7, 2012; Peter Boag, President, Canadian Petroleum Products Institute, Evidence, January 31, 2012. [57] Christopher Smillie, Senior Advisor, Government Relations, Building and Construction Trades Department, Canadian office of the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO), Evidence, February 7, 2012. [58] Ibid. [59] Professor Jack Mintz, Palmer Chair in Public Policy, School of Public Policy, University of Calgary, As an Individual, Evidence, February 7, 2012. [61] Kinder Morgan, Trans Mountain Pipeline Open Season, http://www.kindermorgan.com/business/canada/tmx_openseason.cfm [62] Vivian Krause, As an Individual, Evidence, February 9, 2012. [63] Michael Ervin, Vice-President, Director of Consulting Services, MJ Ervin and Associates, The Kent Group, Evidence, February 2, 2012. [64] Joseph Gargiso, Administrative Vice-President, Quebec, Communications, Energy and Paperworkers Union of Canada, Evidence, February 2, 2012. [65] Professor Larry Hughes, Electrical and Computer Engineering, Dalhousie University, As an Individual, Evidence, February 7, 2012. [66] Joseph Gargiso, Administrative Vice-President, Quebec, Communications, Energy and Paperworkers Union of Canada, Evidence, February 2, 2012; Professor Larry Hughes, Electrical and Computer Engineering, Dalhousie University, As an Individual, Evidence, February 7, 2012. [67] Ibid. [68] Michael Ervin, Vice-President, Director of Consulting Services, MJ Ervin and Associates, The Kent Group, Evidence, February 2, 2012. [69] John Quinn, General Manager, Integration and Planning, Refining and Marketing, Suncor Energy Inc., Evidence, February 2, 2012. [70] In 2011, Enbridge proposed the reversal of its line 9 between Sarnia and Montréal to bring western crude oil to Eastern Canada. According to Brenda Kenny (Evidence, February 7, 2012), Line 9 was originally built in the 1970s in order to address and mitigate concerns about energy security in Eastern Canada, including the potential threat of an OPEC embargo. By the 1990s, the political threat from the Middle East had receded, thereby improving the reliability and affordability of oil imports through the eastern port. Consequently, “the market signalled the need to reverse [the pipeline flow], and oil has been flowing from Montréal into Sarnia [ever since].” [71] Mark Corey, Assistant Deputy Minister, Energy Sector, Department of Natural Resources, Evidence, January 31, 2011. [72] Professor Larry Hughes, Electrical and Computer Engineering, Dalhousie University, As an Individual, Evidence, February 7, 2012. [73] Joseph Gargiso, Administrative Vice-President, Quebec, Communications, Energy and Paperworkers Union of Canada, Evidence, February 2, 2012. [74] John Quinn, General Manager, Integration and Planning, Refining and Marketing, Suncor Energy Inc., Evidence, February 2, 2012. [75] Ibid. [76] Michael Ervin, Vice-President, Director of Consulting Services, MJ Ervin and Associates, The Kent Group, Evidence, February 2, 2012. [77] Natural Resources Canada, document presented to Committee, January 31, 2012. [78] Canadian Petroleum Products Institute, document presented to Committee, January 31, 2012. [79] Ibid. [80] Natural Resources Canada, document presented to Committee, January 31, 2012. [81] Carol Montreuil, Vice-President, Canadian Petroleum Products Institute, Evidence, January 31, 2012. [82] Peter Boag, President, Canadian Petroleum Products Institute, Evidence, January 31, 2012. [83] Natural Resources Canada, document presented to Committee, January 31, 2012. [84] Peter Boag, President, Canadian Petroleum Products Institute, Evidence, January 31, 2012. [85] Ibid. [86] Ibid. [87] Michael Ervin, Vice-President, Director of Consulting Services, MJ Ervin and Associates, The Kent Group, Evidence, February 2, 2012. [88] Joseph Gargiso, Administrative Vice-President, Quebec, Communications, Energy and Paperworkers Union of Canada, Evidence, February 2, 2012. [89] Keith Newman, Director of Research, Communications, Energy and Paperworkers Union of Canada, Evidence, February 2, 2012. [90] According to Keith Newman, Imperial Oil had to close 100 gas stations (or one quarter of its total), Petro-Canada closed 30 stations and imposed rationing at another 80 stations, and Shell Canada had to close 5 stations. [91] Keith Newman, Director of Research, Communications, Energy and Paperworkers Union of Canada, Evidence, February 2, 2012. [92] Ibid. [93] Joseph Gargiso, Administrative Vice-President, Quebec, Communications, Energy and Paperworkers Union of Canada, Evidence, February 2, 2012. [94] Michael Ervin, Vice-President, Director of Consulting Services, MJ Ervin and Associates, The Kent Group, Evidence, February 2, 2012. [95] Keith Newman, Director of Research, Communications, Energy and Paperworkers Union of Canada, Evidence, February 2, 2012. [96] Ibid. [97] According to Keith Newman (Evidence, February 2, 2012), a 2011 Conference Board of Canada (CBC) report estimates that the closure of 10% of refining capacity in Canada would result in the loss of “38,300 person years of work, $4 billion of cumulative GDP, and $508 million of provincial and federal income taxes [...]”. [98] Keith Newman, Director of Research, Communications, Energy and Paperworkers Union of Canada, Evidence, February 2, 2012. [99] John Quinn, General Manager, Integration and Planning, Refining and Marketing, Suncor Energy Inc., Evidence, February 2, 2012. [100] Peter Boag, President, Canadian Petroleum Products Institute, Evidence, January 31, 2012. [101] Professor Michal Moore, School of Public Policy and ISEE Core Faculty, University of Calgary, As an Individual, Evidence, February 7, 2012. [102] Ibid. [103] National Energy Board, The current and future state of oil and gas pipelines and refining capacity in Canada, Follow-up document submitted to the Committee on February 16, 2012. [104] Professor Larry Hughes, Electrical and Computer Engineering, Dalhousie University, As an Individual, Evidence, February 7, 2012. [105] Joseph Gargiso, Administrative Vice-President, Quebec, Communications, Energy and Paperworkers Union of Canada, Evidence, February 2, 2012; Professor Larry Hughes, Electrical and Computer Engineering, Dalhousie University, As an Individual, Evidence, February 7, 2012. [106] Professor Larry Hughes, Electrical and Computer Engineering, Dalhousie University, As an Individual, Evidence, February 7, 2012. [107] Professor Jack Mintz, Palmer Chair in Public Policy, School of Public Policy, University of Calgary, As an Individual, Evidence, February 7, 2012. [108] Robert Reid, President, Mackenzie Valley Aboriginal Pipeline LP, Evidence, February 9, 2012. [109] Ibid. [110] Ibid. [111] Professor Michal Moore, School of Public Policy and ISEE Core Faculty, University of Calgary, As an Individual, Evidence, February 7, 2012 [112] Ibid. [113] Peter Boag, President, Canadian Petroleum Products Institute, Evidence, January 31, 2011. [114] Brenda Kenny, President and Chief Executive Officer, Canadian Energy Pipeline Association, Evidence, February 7, 2012. [115] Christopher Smillie, Senior Advisor, Government Relations, Building and Construction Trades Department, Canadian office of the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO), Evidence, February 7, 2012. [116] John Quinn, General Manager, Integration and Planning, Refining and Marketing, Suncor Energy Inc., Evidence, February 2, 2012. [117] Professor Larry Hughes, Electrical and Computer Engineering, Dalhousie University, As an Individual, Evidence, February 7, 2012. [118] Professor Michal Moore, School of Public Policy and ISEE Core Faculty, University of Calgary, As an Individual, Evidence, February 7, 2012 [119] Mark Corey, Assistant Deputy Minister, Energy Sector, Department of Natural Resources, Evidence, January 31, 2011. |