INDU Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

CHAPTER 5:

POLICY INSTRUMENTS AND OPTIONS

The numerous challenges to the Canadian manufacturing sector posed by the profound structural change in the Canadian economy that were described in the previous four chapters necessitate policy responses from the Government of Canada. Industrial policy in Canada must change to reflect the new economic circumstances. In this chapter, the Committee analyses the recommendations offered by witnesses (see Appendix D). We traverse a policy landscape that includes monetary, taxation, energy, labour, trade, protection of intellectual property rights, infrastructure, regulatory, and research, development and commercialization in the search for a new, federal industrial policy framework that would assist and complement the Canadian manufacturing sector's productivity and competitiveness agenda.

Monetary Policy

In assessing Canadian monetary policy over the past six years, one must first understand its institutional framework which rests on two pillars: a flexible currency exchange rate and the Bank of Canada's independent exercise of its inflation-control targeting tactics. The current floating currency exchange rate regime was adopted by the Finance Minister of the day in May 1970 in the midst of a positive terms of trade shock (in this case, a worldwide resource commodities boom that resulted in soaring Canadian export prices relative to import prices) that put upward pressure on inflation. To relieve these inflationary pressures, the dollar was allowed to float; market forces (which were very strong and positive at the time — not unlike those that prevail today) were to determine its external value.

After a period of targeting the narrowly defined monetary aggregate known as M1[30] (1970-1982) and a return to its operational target for the Bank Rate[31] (1982-1991), the Bank of Canada has pursued a strategy of inflation-control targeting. In February 1991, the Government of Canada and the Bank of Canada agreed to introduce targets aimed at reducing the rate of inflation. The objective was to achieve a 3% inflation rate, as measured by the consumer price index (CPI), by the end of 1992 and to gradually reduce the rate of inflation to 2% by the end of 1995. This last target was extended four times by agreement and all extensions also involved maintaining a target range of 1% to 3%. The latest Government of Canada-Bank of Canada inflation-control target agreement commenced in January 2007 and will continue until 31 December 2011.

The Bank of Canada Governing Council's main tool for implementing monetary policy is the target for the Overnight Rate.[32] This rate is normally set on eight fixed dates per year.[33] Prior to the appreciation of the Canadian dollar, the Bank of Canada's Overnight Rate was set at slightly more than a half percentage point above that of the U.S. Fed Rate. This gap increased to as much as 2.2 percentage points in July 2003 but has averaged slightly more than a full percentage point between February 2002 and February 2005. Since that time, the Bank of Canada's Overnight Rate has been almost a full percentage point below that of the U.S. Fed Rate (see Figure 21).

Source: Bank of Canada

Monetary policy is, of course, pan-Canadian in scope and cannot be manipulated to address the specific circumstances of either one sector of the economy or one region of the country. It is also important to recognize that it is not possible for a central bank to successfully control both domestic and external values of its currency at the same time. With only one policy instrument — the Overnight Rate — a central bank can have only one target: the rate of inflation (i.e., the domestic value of the currency). The external value of the currency is determined by the market, and thus a floating currency exchange rate regime has managed the adjustment necessitated by both improving and deteriorating terms of trade in the past decade.

The Committee recognizes that the Bank of Canada has been within its 1-3% inflation target range 32 times in the past 40 quarters. Furthermore, the Bank of Canada's setting of the Overnight Rate at a discount to that of the U.S. Fed Funds Rate in the past two years indicates that the Governor of the Bank of Canada is accounting for the rising value of the Canadian dollar in its policy decision-making. The Committee acknowledges:

The Government of Canada's decision to renew its inflation-control target agreement with the Bank of Canada that would allow it to target the consumer price index (CPI) rate of inflation at the 2% midpoint of a 1% to 3% range for a period of five years ending in 2011.

Taxation Policy

Tax relief in various forms was suggested by most witnesses and was not limited in its application to the manufacturing sector. The tax measures recommended most often included: an increase in the capital cost allowance (CCA) rates for machinery and equipment used in manufacturing and processing activities, and railway rolling stock, locomotives and inter-modal equipment; a lowering of the corporate tax rate beyond the current schedule[34]; and an expansion of the Scientific Research and Experimental Development (SR&ED) Tax Incentive Program. These recommendations would apply not solely to the manufacturing sector but to the business sector at large.

1. The Capital Cost Allowance Regime

The Committee deliberated extensively on a number of recommendations for change of the CCA rates applicable to certain equipment made by witnesses, with particular attention paid to two of them:

- A two-year write-off period for investments in new

manufacturing and processing (M&P) equipment and equipment associated with information, energy

and environmental technologies; and

- A capital cost allowance rate of 30% for rolling stock, locomotives and inter-modal equipment.

To fully appreciate the novelty of these suggested treatments and the additional costs (in the form of revenue cost) they would imply for the federal treasury, a review of the current CCA regime is in order. Presently, capital investment expenditures cannot be written off entirely in the year incurred for income tax purposes. Rather, this expenditure/cost may be written off at the CCA rates that are permitted under the Income Tax Act, similar to the concept of depreciation used in financial statements. In time, these annual deductions that may be claimed under the CCA regime will result in virtually the entire capital cost being allowed as a deduction from income by the taxpayer. In the case of specific equipment that depreciates at a faster rate than implied by the CCA rate for the class of equipment to which it belongs, taxpayers can make an election for terminal loss to be claimed upon disposition of the equipment. Finally, Finance Canada's approach in setting the CCA rate for a particular class of assets is based on the general principle that this rate reflects the "useful life" of the asset in question — this ensures investment decisions reflect economic and not tax considerations.

The Committee understands that the current CCA regime allows for most M&P equipment to be depreciated at the declining balance rate of 30%. An expected benefit of accelerating the write-off period to two years would be a faster turnover of capital and a higher rate of investment. Finance Canada indicates that the revenue cost of permitting machinery and equipment used in manufacturing and processing to be fully deducted in two years — actually, three years because of the half-year rule — is estimated to cost the Government of Canada approximately $2.3 billion over five years. Such a change would also have a significant revenue cost for provinces that have signed a tax collection agreement with the federal government. The revenue cost of providing the same treatment for equipment associated with information, energy and environmental technologies could not be determined without further details on the specific design of such a measure, including the specific types of assets that would be eligible.

The Committee concludes that the benefits of accelerating the CCA rates for M&P equipment and equipment associated with information, energy and environmental technologies are likely to exceed its costs. The Committee further believes that this special treatment should be extended to the business sector as a temporary measure and would be renewable based on periodic review and assessment of its benefits and costs. The Committee, therefore, recommends:

That the Government of Canada modify its capital cost allowance for machinery and equipment used in manufacturing and processing and equipment associated with information, energy and environmental technologies to a two-year write-off (i.e., 50% using the straight-line depreciation method) for a period of five years. This measure would be renewable for further five-year periods upon due diligence review by a parliamentary committee.

The Committee was made aware by the Canadian Association of Railway Suppliers (CARS) that the current federal CCA rates governing the depreciation of rail's rolling stock (15%) and track infrastructure (10%) are significantly lower than those of the United States. With these rates, it takes Canadian railways more than 20 years to fully depreciate their rolling stock assets. In contrast, U.S. tax rules allow railway companies to fully depreciate their rolling stock assets in seven years. As such, CARS claims that identical rail investment projects require a 23% higher level of earnings in Canada than in the United States to yield the same rate of return. Consequently, and particularly since continental free trade, a U.S. company that leases equipment to a Canadian railroad will likely buy this equipment from a U.S. supplier, not a Canadian supplier.

The Committee is convinced that the U.S. government's CCA rates for railway rolling stock and infrastructure, which deviate significantly from those that would reflect the "useful life" of these assets, create an uneven playing field between Canadian and U.S. railway equipment suppliers that must be met in kind. The Committee, therefore, recommends:

That the Government of Canada raise the capital cost allowance rate for rolling stock, locomotives and inter-modal equipment to 30% using the declining-balance depreciation method.

2. The Scientific Research and Experimental Development (SR&ED) Tax Incentive Program

Canada's SR&ED tax incentive program is one of the most advantageous in the industrialized world, providing more than $2.6 billion in deductions or credits to Canadian businesses in 2005. The tax incentives for SR&ED come in two forms: (1) income tax deductions and (2) investment tax credits (ITCs) for SR&ED conducted in Canada. In terms of income tax deductions, current expenditures (e.g., salaries of employees directly engaged in SR&ED, the cost of materials consumed in SR&ED, overhead) and capital expenditures on machinery and equipment are fully deductible in the year incurred. Unused deductions may be carried forward indefinitely. In terms of ITCs, there are two rates under SR&ED:

- the general rate of 20%; and

- an enhanced credit rate of 35% for smaller Canadian-controlled private corporations (CCPCs) on their first $2 million of eligible expenditures; these ITCs are refundable to smaller CCPCs at a rate of 100% on current expenses and 40% on capital expenses.

ITCs may be deducted from federal taxes otherwise payable. Unused ITCs may be carried back 3 years or carried forward 20 years.

The Committee deliberated on a number of suggestions for change to the SR&ED tax incentive program made by witnesses. In the end, the Committee focused on the impact of one recommendation that combined most witnesses' suggestions along the following lines:

- An improved SR&ED Tax Incentive Program that would make the tax credits refundable to all firms, exclude them from the calculation of the tax base, provide an allowance for international collaborative R&D, and extend the tax credit to cover patenting, prototyping, product testing, and other pre-commercialization activities.

The Committee understands that business R&D intensity (expenditure as a percentage of GDP) in Canada is lower than the OECD average, and that the business sector both funds and performs a lower percentage of total national R&D than does the business sector in other OECD countries.[35] The above recommendation addresses virtually all of the barriers of access to the SR&ED tax incentive program mentioned by the witnesses and would likely encourage more R&D activities by the private sector in Canada.

Finance Canada suggests that the cost of extending full refundability of SR&ED ITCs to all firms and all types of expenditures would depend on the treatment of existing pools and unused ITCs. Depending on whether the application of ITC pools to current taxes would affect the refund available, the fiscal cost of refundability is estimated to be between $5 billion and $10 billion over five years.

Finance Canada indicates that the cost of excluding SR&ED ITCs from the tax base would depend on whether the proposal would apply only to federal ITCs, or include provincial ITCs for R&D, and whether the change in allowable expenditures for the purpose of the tax deduction would also flow through to qualified expenditures for the ITCs. Depending on how the change is implemented, the fiscal cost is estimated to be between $1 billion and $4 billion over five years.

Finance Canada concludes that the cost of providing an allowance for international collaborative R&D would depend on the definition of this activity and the type of allowance provided. Based on Statistics Canada data on industrial payments for R&D and other technical services abroad, and assuming the allowance would be provided by including expenditures for such activities in the base for the ITC, the fiscal cost of this proposal is estimated to be $2.2 billion over five years.

Finance Canada did not provide the Committee with an estimate of the cost of extending the tax credit to cover patenting, prototyping, product testing, and other pre-commercialization activities because there was no data readily available on the size of corporate expenditures on these items.

Excluding the proposal to extend the tax credit to cover these other activities, the fiscal cost of implementing the above SR&ED measures would vary from $8.2 billion to $16.2 billion over five years. The Committee believes that increased R&D will lead to increased employment levels in the manufacturing sector. Given the extent of the fiscal costs to the above suggested changes, the Committee recommends:

That the Government of Canada improve the Scientific Research and Experimental Development (SR&ED) Tax Incentive Program to make it more accessible and relevant to Canadian businesses. The government should consider making the following changes:

- make the investment tax credits fully refundable;

- exclude investment tax credits from the calculation of the tax base;

- provide an allowance for international collaborative research and development; and

- expand the investment tax credits to cover the costs of patenting, prototyping, product testing, and other pre-commercialization activities.

Energy Policy

Industrial[36] energy use is the biggest single component of energy demand in Canada (39% of total demand in 2002). Of that demand, 30% is from energy industries themselves (mostly the upstream oil and gas industry), and 27% from the pulp and paper sector (2002 data). Industrial energy use increased by approximately 17% between 1990 and 2002. This increase was the result of an increase in industrial activity, which grew by about 44%. Gains in energy efficiency (between 1996 and 2002, energy intensity decreased by 11%) and structural changes in the economy (the relative increase in the activity of less energy intensive industries) have partially offset increased demand for energy. Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from the industrial sector increased by 15% between 1990 and 2002. However, a significant shift towards the use of less GHG-intensive fuels in the industrial sector has meant that the level of GHG emissions is lower than it would have been otherwise.[37]

Abundant, secure supplies of energy are essential for the manufacturing sector. The key energy sources for industry are natural gas (30%); electricity (26%); refinery fuel oils, coke and still gas (23%); wood waste and pulping liquor (14%); and coal, coke oven gas, liquid petroleum gas and gas plant natural gas liquids, steam and waste fuels (8%).[38] Data presented to the Committee by the Canadian Federation of Independent Business and the Canadian Manufacturers and Exporters suggest that rising and/or unpredictable energy prices are one of the major business factors adversely affecting firms in the manufacturing sector. This is especially true for energy-intensive industries such as pulp and paper, chemical, petroleum refining and primary metal, which make up about 29% of Canada's manufacturing GDP.

Canada, with its large oil sands deposits as well as coal and natural gas resources, has one of the largest supplies of hydrocarbons in the world. In addition, Canada has significant capacity for hydroelectric and nuclear production. Despite this abundant supply of energy, there are problems in Canada's overall future energy picture. Given increasing geopolitical tensions, supply disruptions (e.g., because of natural disasters or weather problems), environmental and climate change problems, and increased market and price instability, a "business as usual" approach with respect to energy consumption and supply is not sustainable. Required changes include: development of lower carbon footprint energy sources; integration of energy sources, distribution and markets; accelerated development of renewable and alternative energy sources; emphasis on the development and deployment of new technologies; a responsive regulatory environment; and a more certain and stable business environment.[39]

Many witnesses appearing before the Committee called on the federal government to work with the provinces to implement an energy framework that would articulate a national energy vision for Canada. This vision would provide a clear policy framework on regulation, energy R&D, commercialization, energy efficiency, and environmental issues, among other items, and would indicate how the various components are tied together.

The provinces have the constitutional responsibility for natural resources and are responsible for most aspects of the regulation and promotion of the energy sector within their borders. The federal government is responsible for inter-provincial facilities and international and inter-provincial trade. Through regulatory and fiscal measures, it can facilitate and support research, development and investment in the energy sector.

The Committee recognizes the importance of energy to the future of manufacturing and the need to develop cleaner energy sources. It has also duly noted the comments and findings included in the report of the National Advisory Panel on Sustainable Science and Technology. The Panel called for an increased focus on energy science and technology (S&T) to ensure long-term growth and sustainability in the Canadian economy. In particular, the Panel recommended increased funding support for innovation from governments (both federal and provincial), and the private sector. It also defined a number of key priorities for sustainable energy S&T in Canada. They include bio-energy; gasification; CO2 capture and storage; electricity transmission, distribution and storage; and fuel cells.[40]

The Committee has noted five recommendations in particular made by the Panel that pertain specifically to the federal government:

Double the federal government's investments in real terms in energy research and development within the next 10 years.

Provincial and Federal governments should work together to develop clear and consistent long-term market signals to address environmental issues such as climate change.

In large, commodity-based energy industries, governments should consider using regulation or financial incentives to stimulate private sector funding for research to address common, long-term economic and environmental issues.

The federal government should provide $30 million to leverage investment in a reputable and visionary private sector investment in a Canadian venture capital fund that is focused on energy technologies. Such a strategic investment should be made on a recurring basis to support the ongoing development and growth of innovative, knowledge-based Canadian energy technology companies;

Federal energy research labs should conduct a systematic review of their mission, roles and objectives in the context of a federal energy strategy. They should then undergo a review of their activities, by external peers among others, to evaluate their ability to deliver on these goals and objectives, and to assess the effectiveness of existing structures and programs in advancing an energy strategy.

Like the National Advisory Panel on Sustainable Science and Technology, the Committee recognizes the need to develop sustainable energy in Canada and sees this as an outstanding opportunity for technological innovation and economic development. The development of clean and renewable energy sources is an unavoidable challenge for Canada. As such, the Committee recommends:

That the Government of Canada review its policies and regulatory and fiscal measures to ensure that they make a greater contribution to the development of clean and renewable energy sources, foster research and development in this area and provide greater support to companies and provinces engaged in these activities.

The Committee also endorses the National Advisory Panel's recommendation that the energy sector increase its R&D spending.

Labour Policy

Over the past decade, three main factors have shaped Canada's workforce: (1) an increasing demand for skills in the face of advanced technologies and the "knowledge based economy"; (2) a working-age population that is increasingly made up of older people; and (3) a growing reliance on immigration as a source of skilled labour. Added to this mix of long-term trends is a recent structural development that is forcing a reallocation of labour both from one sector of the economy to another and from one region of the country to another.

Data from the 2001 Census (2006 Census data are not yet available) indicate that between 1991 and 2001, the number of people in the labour force increased by 1.3 million. Almost half of this growth occurred in highly skilled occupations that generally require university qualifications, whereas low skilled occupations requiring a high school (or less) education accounted for only a quarter of the increase.[41] The data also show that Canada's workforce is aging, and that the median age of retirement has decreased (falling from 62.0 between 1992 and 1996 to 60.8 between 1997 and 2001).[42]

The combination of an aging population, a lower retirement age, fewer young people entering the working-age population (because of low fertility rates), increased demand for workers with specialized skills, and international worker mobility has led (or may lead) to labour shortages in some areas of the economy. Canada has increasingly turned to immigration as a source of skilled labour. Data from the 2001 Census show that immigrants who arrived in Canada during the 1990s, and who were in the labour force in 2001, represented almost 70% of the total growth of the labour force over the decade. If current immigration rates continue, it is possible that immigration could account for virtually all labour force growth by 2011.[43]

The rapid and significant appreciation in the value of the Canadian dollar since 2002 has made many manufacturers less competitive relative to foreign competitors. They have had to both shed employees and invest more in capital machinery and equipment to raise their labour productivity levels and, in turn, stabilize their production levels and competitiveness. Given that national employment levels have risen to all-time highs and national unemployment rates have declined to modern day lows (i.e., lowest levels in 30 years), primary commodities and services sectors are engaging many of the skilled workers laid-off by the manufacturing sector. Despite the fact that manufacturing firms have been laying-off workers, many firms (sometimes the same ones) are faced with a lack of skilled labour for certain work (see Chapter 2).

Slower economic growth induced by a labour skills shortage can be mitigated or countered by taking actions to: (1) increase the participation rate of those not fully participating in the labour force; (2) increase the value of work performed per person of those already in the labour market; and/or (3) increase the skill levels of those entering the labour force. Individuals falling within this first category include, amongst others, older skilled workers who are considering retirement in the immediate or near future, and immigrant workers whose skills accreditation are not recognized or who, along with Aboriginals, are not fully integrated into the labour market for reasons such as language or cultural barriers. Individuals falling within the second category include (employed and unemployed) workers whose skills can be upgraded through further training or education. Individuals falling within the third category include Canadian youth who are pursuing further education or vocational training and new working-age immigrants to the country.[44]

In the following sections, the Committee addresses three government policy instruments that could be employed to supplement measures used by employers (e.g., higher wages) to deal with the actual (or potential) shortage of skilled labour across different sectors of the economy.

1. Accreditation of Skilled Immigrants

Many immigrants to Canada, though well-educated and highly skilled, face barriers in obtaining recognition of their qualifications, training and experience. A survey of 2000 Canadian employers, conducted at the end of 2004, indicated that although Canadian employers generally have positive attitudes towards immigrants and immigration, many continue to overlook immigrants in their human resource planning, do not hire immigrants at the level at which they were trained, and face challenges trying to integrate recent immigrants into their workforce.[45]

The Government of Canada, led by the Minister of Human Resources and Social Development, in consultations with the provinces and territories and other stakeholders, has recently begun work on deciding on the mandate, structure and governance of a Canadian agency for the assessment and recognition of foreign credentials. The agency would be devoted to ensuring foreign-trained immigrants meet Canadian standards and helping foreign-trained immigrants secure jobs in their areas of expertise more quickly. The government's Budget Plan 2006 set aside $18 million over two years for the establishment of such an agency.

Given that immigration could account for virtually all labour force growth by 2011, and that many sectors of the economy will likely experience skilled labour shortages over the next decade, the Committee recommends:

That the Government of Canada, with the consent of the Council of Ministers of Education, place a high priority on establishing the agency responsible for the assessment and recognition of foreign credentials.

2. Temporary Foreign Worker Program

The Temporary Foreign Worker Program allows employers to hire foreign workers to meet their human resource needs when Canadian workers are not readily available. The Program is jointly administered by Citizenship and Immigration Canada and Human Resources and Social Development Canada/Service Canada, and operates under the authority of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act and Regulations.

In November 2006, the federal government announced improvements to the Temporary Foreign Worker Program to make it easier for employers in Alberta and British Columbia to hire foreign workers when there are no Canadian citizens or permanent residents available to fill the position. The federal government has indicated that it plans to expand the program to include "occupations under pressure" in other regions of the country as well.[46] Although Western Canada has been hit particularly hard by shortages of all types of labour, other areas of the country are also experiencing labour shortages. The Committee therefore recommends:

That the Government of Canada immediately expand improvements to the Temporary Foreign Worker Program to make it easier for employers across Canada to hire foreign workers when there are no Canadian citizens or permanent residents available to fill the position. The Government of Canada should require that employers taking advantage of this program provide working conditions that are consistent with federal and/or provincial standards for the occupation and workplace.

3. Tax Credits for Employer-financed Workforce Training

The reallocation of labour described above has, in some cases, been insufficient in terms of the number of potential employees available or in matching skill sets with demand, and has prohibited some companies and industries from meeting rising demand for their goods. Improving employee skills through on-site training or by sending employees to training programs are ways for firms to deal with a lack of skilled labour. Employees with enhanced skills not only help the company providing the training, but they are more marketable in the long term, and less likely to draw Employment Insurance, or to draw it for shorter periods of time, in the future.

The cost of paying for training and temporarily losing employees while they are participating in training activities often prohibits companies, especially small and medium-sized enterprises, from providing training to their employees. Furthermore, since employees that have upgraded their skills are more marketable, they may seek other, more lucrative employment opportunities, especially in tight labour markets, once their training is complete; the company providing the training may therefore reap little or no benefit from the training for which it has paid.

As an incentive to encourage companies to provide employer-financed training, the Committee recommends:

That the Government of Canada provide tax credits and/or other measures to companies providing employer-financed training to their employees.

4. Support for Postsecondary Students Conducting Research in Conjunction with Industry

Some of the witnesses who appeared before the Committee noted that university and college graduates looking for work in the manufacturing sector do not always have the required research or business skills to work in the sector. Although Constitutional jurisdiction for education rests with the provinces, there are ways that the federal government supports higher education: through the Canada Social Transfer; by providing support for infrastructure, research and scholarship in universities and colleges; by offering student loans; and by supporting international education. The Committee recognizes these jurisdictional boundaries but notes that there are appropriate avenues that the federal government can pursue to respond to the specific concerns raised by the manufacturers.

For example, two federal granting agencies (the Canadian Institutes for Health Research and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada) offer programs that support postsecondary students and postdoctoral fellows conducting research in industry. These awards generally consist of a scholarship or fellowship from the granting agency, and a minimum cash supplement from the company hosting the student or fellow. Depending on the level (i.e., undergraduate, postgraduate or postdoctoral) of the award, the programs' goals include encouraging graduates in science and engineering to gain experience and seek careers in Canadian industry, and facilitating the transfer of expertise and technology between academia and industry.

The Committee believes that programs that provide support to students and postdoctoral fellows who have interests in industrial research and who will gain the necessary skills to contribute to and enhance R&D in Canadian industry are very valuable. As such, the Committee recommends:

That the Government of Canada, complying with the constitutional division of powers, provide increased funding to programs that support postsecondary students and postdoctoral fellows conducting research in industry.

5. Labour Mobility

Unimpeded labour mobility is an important component of an efficient labour market. The Agreement on Internal Trade (AIT), signed in 1994, requires that provinces and territories eliminate barriers to labour mobility such as residency requirements for registration and unnecessary fees and delays. It also requires governments to: mutually recognize the qualifications of workers already qualified in other provinces/territories; reconcile differences in occupational standards; and put in place accommodation mechanisms to help workers acquire any additional competencies they need related to differences in scope of practice across jurisdictions.

Despite this agreement there continue to be inter-provincial barriers to labour mobility; progress is being made in removing these barriers but it has been slow. In September 2006, the Committee of Federal-Provincial-Territorial Ministers Responsible for Internal Trade came to an agreement on an action plan on internal trade. A key component of the action plan is a strategy to improve labour mobility so that by 1 April 2009, Canadians will be able to work anywhere in Canada without restrictions on labour mobility (i.e., full compliance with the labour mobility provisions of the AIT). The Committee supports:

Agreements recently concluded on construction labour mobility between Quebec and Ontario and on trade, investment and labour mobility signed by Alberta and British Columbia. The Committee believes that removing all additional barriers to labour mobility within Canada is an important means of dealing with regional shortages of skilled labour and ultimately leads to a better allocation of labour within the country.

Trade Policy

1. Canada-South Korea and Canada-EFTA Free Trade Agreements

As a trading nation, Canada remains committed to multilateral trade and its rules-based system that underpin commercial relations with the 148 other member countries of the World Trade Organization (WTO). Canada's first priority on matters of trade continues to be the enhancement of the multilateral trade system, including the conclusion of an agreement based on the "Doha Development Agenda" launched in November 2001. As part of its prosperity initiative, Canada has also negotiated a bilateral free trade agreement with Chile, Costa Rica, Israel and the United States and a regional free trade agreement with Mexico and the United States.

To further its prosperity initiative, Canada is currently negotiating bilateral free trade agreements with the Dominican Republic, the Republic of Korea and Singapore, and regional free trade agreements with the Americas (Free Trade Agreement of the Americas), the Andean Community Countries (Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru and Venezuela), CARICOM (the Caribbean Community), the Central American Four (El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras and Nicaragua), and the European Free Trade Association (EFTA), which includes Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland.

In particular, Canada's trade initiatives with South Korea and EFTA are advancing, with a number of important issues and details left to be negotiated. The Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade (DFAIT) views South Korea as a gateway to Northeast Asia, a region of strategic importance to Canadian manufacturers that have established global value chains, and a free trade agreement with the EFTA countries as a strategic platform for expanding commercial ties with these countries in particular and the European Union in general. Moreover, the latter would put Canada ahead of the United States and on an equal footing with competitors, such as Mexico, Chile, Korea and the European Union (EU) that already have a free trade agreement with EFTA.

In terms of South Korea, with a population of 48 million and a GDP approaching $1 trillion, it is the largest of the four "Asian tigers" and is the world's eleventh largest economy. In terms of EFTA, when these nations are combined and treated as one, this group would rank as Canada's 8th largest merchandise export destination. Norway and Switzerland are ranked as Canada's 13th and 19th most important trading partners in terms of merchandise exports.

These two trade initiatives were raised by witnesses who appeared before the Committee, winning the support of a number of manufacturers. Yet automobile, tool, die and mould manufacturers have reservations on a free trade agreement with South Korea, and shipbuilders and labour union representatives have reservations on both initiatives. Their preoccupations focus on matters relating to non-tariff barriers in both South Korea and EFTA countries that make market access for Canadian firms difficult; Norwegian shipbuilding subsidies and rules of origin for ship sub-assembly components that would lead to an uneven playing field in the Canadian market; and the absence of "fair" labour and environmental standards in South Korea.

These same witnesses also complained about the lack of available information and analyses on the impact that these two free trade agreements would have on particularly vulnerable industries and employment. They claim that either DFAIT has not done the necessary work, or when it has been done, DFAIT has either not disclosed it to the public or has done so only belatedly. The Committee therefore recommends:

That the Government of Canada, through the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade, complete and disclose to the public, in a timely manner, all important impact analyses of any free trade agreements with South Korea and the European Free Trade Association on specifically vulnerable industries and on employment.

The Committee also reiterates the concerns expressed by Canadian manufacturers on the importance of eliminating South Korean and Norwegian non-tariff barriers to enable Canadian businesses to gain market access to these countries.

2. Trade Protection: Anti-Dumping, Countervail and Safeguards

China and India are rapidly industrializing countries, but this development is a double-edged sword for Canadian businesses. Growing Chinese and Indian markets present many opportunities for Canadian exporters, but they also represent a growing challenge for Canadian producers in both their domestic and American export markets. In particular, China has adopted a lengthy set of government measures, including direct and indirect subsidies, market protection and other measures which support its export growth, in order to develop what it believes are critical industries such as steel and steel products. This rapid build-up of capacity through subsidies, the production of which often ends up in the international markets, inevitably results in market distortions in Canada and elsewhere.

According to Canadian steel producers, China appears to be the only country in the world where their export prices are lower than their domestic prices, which suggests "dumping." The Canadian steel industry, among others, wants the government to recognize the importance of applying existing trade rules when "unfair" trade distorts markets for Canadian manufacturing companies. These manufacturers believe these "unfair" practices should be addressed before bigger problems and trade frictions develop.

Witnesses also raised concerns on why Canada has chosen not to impose safeguard measures on selected foreign products, such as Chinese textiles and textile products, whereas other WTO signatory members, including the United States and the European Union, have already imposed them.[47] For more clarity on this issue, the Committee understands that safeguards are temporary trade measures applied by a government on an emergency basis against increased imports of a particular good that are causing or threatening to cause serious injury to its domestic industry producing like or directly competitive products. Such measures can take the form of either tariff increases or quantitative restraints. In Canada, the Canadian International Trade Tribunal (CITT) conducts safeguard inquiries upon complaint by a domestic producer or the Governor in Council and reports its findings to the government, which ultimately decides whether or not to apply safeguards and the form any such measures will take.

The Committee takes note of these industry concerns regarding an apparent divergence between Canadian trade law and its application and believes more information is required. The Committee, therefore, recommends:

That the Government of Canada conduct an internal review of Canadian anti-dumping, countervail and safeguard policies, practices and their application to ensure that Canada's trade remedy laws and practices remain current and effective. This review would also include comparisons with other World Trade Organization members such as the European Union and the United States.

Intellectual Property Rights Protection Policy

Counterfeiting of goods started as a localized industry focused on the copying of high-end designer products, and has developed into a sophisticated global business involving the manufacturing and sale of counterfeit[48] versions of a large range of products, including software, electrical products, batteries, cigarettes, alcoholic beverages, golf clubs, automobile parts, motorcycles, and pharmaceutical products. Although it is difficult to quantify levels of any illegal activity, a 1998 OECD study[49] estimated that trade in counterfeit goods is valued at more than 5% of world trade. The high level can be attributed to a number of factors: (1) advances in technology; (2) increased international trade and emerging markets; and (3) more products that are attractive to copy, such as branded clothing and software. The OECD is currently conducting another survey of governments and industry to assess the economic impact of the counterfeiting problem today. In Canada, the Canadian Manufacturers and Exporters estimate that the counterfeit industry is worth $20-30 billion dollars annually.[50] In addition to the counterfeiting of trademarked products described above, intellectual property (IP) theft also involves the piracy of copyright products in digital and analogue formats.

According to international agreements, Canada must provide effective criminal enforcement against willful trade-mark counterfeiting and copyright piracy on a commercial scale, as well as to implement border measures to prevent the importation of counterfeit and pirated goods. For example, both the WTO Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) and NAFTA require criminal enforcement and border measures. Canada does have legislation against both trade-mark offences (in the Criminal Code)and copyright offences (in the Copyright Act). Despite the existence of this legislation, Canada continues to find itself on the United States Trade Representative's (USTR) Special 301 Watch List, which examines IP rights protection in 87 countries.[51] Canada was placed on the list once again in 2006 because it has not ratified and implemented the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) Internet Treaties, does not, according to the USTR, provide adequate and effective protection of copyrighted works in the digital environment, and has no legislation to protect against unfair commercial use of undisclosed test and other data submitted by pharmaceutical companies seeking marketing approval for their products.[52] The USTR also suggests that Canada needs to improve its IP rights enforcement system so that it can take effective action against the trade in counterfeit and pirated products within Canada, as well as curb the amount of infringing products transiting through Canada.

The Committee heard from several manufacturers who described problems that they are experiencing with counterfeit versions of their products being sold in Canada and other markets. Problems cited with respect to IP protection include the time and expense involved in pursuing patent infringement cases through the courts; inadequate enforcement by Canadian officials at the border; and the difficulty in dealing with patent infringement in countries, particularly China, which are allegedly not respecting their obligations under TRIPS. Some manufacturers suggested that these problems were a disincentive to innovate.

Although counterfeiting was the focus of the manufacturers' complaints, the Committee shares the concerns expressed about copyright piracy in recent position papers by the Canadian Anti-Counterfeiting Network[53] and by the Canadian Manufacturers and Exporters. The Committee therefore wishes to address both issues and makes the following recommendation:

That the Government of Canada immediately bring forth legislation to amend the Copyright Act; ratify the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) Copyright Treaty (WCT) and the WIPO Performances and Phonograms Treaty (WPPT); amend related acts; and ensure appropriate enforcement resources are allocated to combat the scourge and considerable economic and competitive damage to Canada's manufacturing and services sectors, and to Canada's international reputation by the proliferation of counterfeiting and piracy of intellectual property.

Regulatory Policy

1. Regulatory Modernization

Governments use regulation in combination with other instruments, such as taxation, program delivery and services, and voluntary standards to achieve important public policy objectives. Regulations can be beneficial to businesses by creating an environment in which commercial transactions take place in predictable ways, consistent with the rule of law. Complying with regulations can, however, be a costly endeavour, and hits small businesses particularly hard. According to a survey of 7,300 firms conducted by the Canadian Federation of Independent Business, the cost of regulatory compliance is $33 billion annually.[54] Various industry associations have called for streamlined regulations and reduced paper burden as a cost-effective way to increase productivity.

Work on improving Canada's regulatory framework has already been conducted. For example, in 2004, the External Advisory Committee on Smart Regulation submitted a report to the Government of Canada that described how to put the principles of a "smart regulation" framework into practice, and realize the vision of Smart Regulation for Canada over the next three to five years. Its report set out proposed directions and recommendations regarding international regulatory cooperation, federal-provincial-territorial regulatory cooperation, federal coordination, risk management, instruments of government action, the regulatory process, and government capacity.

The Committee believes that, in certain cases, regulation is excessive or duplicative, and that in these cases, regulation is impeding innovation or productivity. As such, the Committee recommends:

That the Government of Canada, in collaboration with provincial, territorial and foreign governments and the private sector, make implementation of a "smart regulation" initiative a priority. In the interests of efficiency, the government should build on the work of previous and current advisory groups in setting its goals for regulatory reform (e.g., the 2004 report of the External Advisory Committee on Smart Regulation, and the recommendations of the ongoing Advisory Committee on Paperwork Burden Reduction).

2. Environmental Regulations

Many energy industry associations complain of the complicated, multi-jurisdictional regulatory processes governing approvals for new investments in energy infrastructure. Additionally, industries in all sectors are concerned about the uncertainty surrounding new environmental regulations related to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and air pollution that may be introduced by the federal government as outlined in the Notice of intent to develop and implement regulations and other measures to reduce air emissions. The federal government intends to set short-term (2010-2015), medium-term (2020-2025) and long-term (2020-2050) emissions targets for air pollutants and GHGs. The short- and medium-term targets for GHGs would be intensity-based such that the absolute level of GHG emissions may increase over the time periods involved. Nonetheless, the targets would have to be restrictive enough to allow for a smooth transition to the long-term goal of an absolute reduction of 45-65% in GHG emissions from 2003 levels by 2050. Consultations are underway to discuss the overall regulatory approach, including short-term targets.

Since clear environmental regulations and unambiguous timetables for implementation of new regulations are essential for companies making new investments in energy infrastructure, the Committee recommends:

That the Government of Canada conclude negotiations related to the implementation of any regulations on the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions and air pollution, and that the process be expedited.

3. The User Fees Act

The User Fees Act came into effect on 31 March 2004, with the aim of strengthening accountability, oversight, and transparency in the management of user fee activities. The Act lists requirements when proposing a new fee or amending an existing fee. Some industry associations maintain that the government is not ensuring that federal departments meet the performance standards that they are required to set under the provisions of the Act. The Committee shares these concerns and recommends:

That the Government of Canada review the requirements of the User Fees Act and ensure that all federal departments are setting and meeting the performance standards and reporting to Parliament as required under the provisions of the Act.

Infrastructure

Manufacturers need access to modern infrastructure to efficiently receive from and ship product to other companies along the supply chain, ship their goods to market, and allow the movement of people across the country. Given that over a third of Canadian manufacturers export more than 50% of what they produce, and only 12% of Canadian manufacturers do not export at all,[55] manufacturers require access to infrastructure that allows easy and rapid access to world markets. Since the U.S. market is extremely important to Canadian manufacturers, efficient functioning of Canada-United States border crossings is essential. Additionally, in order to take advantage of the trade opportunities associated with the growing economies of Asia, Canada's ports on the east and west coast and connecting rail lines must offer unimpeded access to those markets.

Canadian manufacturers are particularly concerned about continued delays at certain border crossings into the United States. The Windsor-Detroit Corridor is Canada's most important entry to the United States, with 28% of goods shipments between Canada and the United States passing through that corridor. Congestion at this crossing has a negative impact on Canada's economy, particularly the automotive industry. Studies have demonstrated that a new crossing between Windsor and Detroit is required to meet long-term capacity needs and add redundancy to the crossing infrastructure. Building a new crossing requires a partnership between the U.S. and Canadian governments, and requires customs plazas and access roads on both sides of the border. The government promised in its recent economic plan, Advantage Canada, that the crossing would be in place no later than 2013.[56]

1. National Gateway and Trade Corridor Policy

The Government of Canada, in Advantage Canada, indicated that it would work towards developing a long-term plan for infrastructure that includes predictable funding for a variety of infrastructure projects, and that it will be implementing a new national gateway and trade corridor policy. Given the importance of modern infrastructure to manufacturers (and Canadians in general), the Committee recommends

That the Government of Canada announce its national gateway and trade corridor policy, and that it respond specifically to the concerns about infrastructure expressed by the Coalition for Secure and Trade-Efficient Borders in its policy.

2. FAST Lanes at Canada-United States Border Crossings

According to a recent report,[57] at several key border crossings there is limited access to dedicated lanes for commercial vehicles in the Free and Secure Trade (FAST) Program. This Program is a joint Canada–United States initiative involving the Canada Border Services Agency and the United States Customs and Border Protection (CBP). FAST supports moving pre-approved eligible goods across the border quickly and verifying trade compliance away from the border. The Committee believes that programs such as FAST are extremely important for the efficient movement of commercial traffic across the border. The Committee therefore recommends:

That the Government of Canada ensure that sufficient, dedicated Free and Secure Trade (FAST) lanes be available for commercial traffic at important crossings, and be staffed to meet traffic demands during peak periods. Where infrastructure limits prohibit such an undertaking, the government should expand or alter the infrastructure to accommodate additional FAST lanes, and other border programs that facilitate trade.

3. Financing Strategy for the New Windsor-Detroit Crossing

In its economic plan Advantage Canada announced in November, the Government of Canada indicated that a financing strategy for the new Windsor-Detroit Crossing would be announced in Budget 2007. A recent announcement by the Minister of Transport suggested that the government will explore the opportunity to partner with the private sector to design, build, finance, and operate the new crossing. Since details of the financing strategy have not been released, the Committee recommends:

That the Government of Canada define its financing strategy for the Windsor-Detroit crossing, including any potential tolls and toll roads associated with the crossing.

Research, Development and Commercialization Policies

One way in which the manufacturing sector can adapt to some of the challenges it is facing is for the sector to increase its R&D and innovation performance in order to improve productivity. A large econometric literature demonstrates the link between R&D and productivity.

1. Industrial R&D Spending in Canada and the OECD

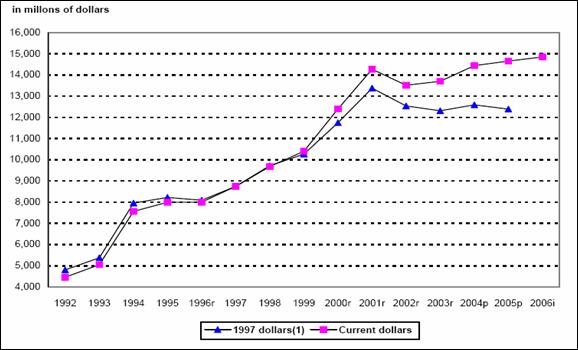

Industrial R&D spending in Canada is projected to reach $14.9 billion in 2006 according to reported intentions. Although absolute spending on industrial R&D (in current dollars) has increased slightly since 2001, spending adjusted for inflation (in 1997 dollars) has declined (see Figure 22). Industrial R&D spending is still recovering from the sharp decline in R&D spending by the information communications technology (ICT) sector, and in particular the communications equipment industry's, that occurred in 2002. At the peak of the "ICT boom" in 2001, R&D spending by these industries represented 46% of industrial R&D; current R&D spending by these industries has leveled off to just below 40%.[58]

Research and Development Spending in Canadian Industry, 1992 to 2006

Source: Statistics Canada, Industrial Research and Development, 2002 to 2006, Science Statistics, August 2006,

http://www.statcan.ca/english/freepub/88-001-XIE/88-001-XIE2006004.pdf.

Between 2002 and 2006 the manufacturing sector's share of industrial R&D spending declined from 61% to 56%, while the services sector's share has increased from 35% to 40%. The industry that showed the strongest decline in its share of industrial R&D, and is primarily responsible for the overall decline in industrial R&D spending in manufacturing, is communications equipment, whose proportion of total industrial R&D spending fell from 15% to 11% between 2002 and 2006. Although the communications equipment industry's share of industrial R&D spending has been declining since 2001, this industry still leads all industries in R&D spending ($1.58 billion in 2006). Information and cultural industries are a close second ($1.52 billion). The next largest industrial R&D spenders continue to be pharmaceutical and medicine manufacturing ($1.29 billion), scientific research and development services ($1.14 billion), and computer system design and related services ($1.06 billion). Ontario and Quebec, which together account for 63% of gross domestic product by province in 2004, were the two provinces that together accounted for four-fifths of industrial R&D in Canada in 2004.

Business R&D intensity (expenditure as a percentage of GDP) in Canada is lower than the OECD average (1.07% vs. 1.53% in 2004; see Figure 23).[59] Additionally, the Canadian business sector, on average, performs a lower percentage of total national R&D than does the business sector in other OECD countries (53% vs. 67% in 2003), and funds a lower percentage of total national R&D than does the business sector in other OECD countries (47.5% vs. 61.6% in 2003).[60]

Business Expenditures on R&D as a % of GDP

by Country, 1995, 2000 and 2004

Source: OECD: Main Science and Technology Indicators Database, July 2006. [61]

Various explanations have been proposed as to why Canadian businesses, on average, performs and finances relatively little R&D. One of the explanations centres around Canada's industrial structure: a relatively large resource sector, which is not R&D intensive compared to other sectors (e.g., high-technology); a large proportion of small and medium-sized enterprises, which may have difficulty in financing and performing certain types of R&D; and the relatively large proportion of foreign-owned firms in Canada, whereby most R&D may be conducted at the firms' headquarters that are located abroad.[62] Another explanation points to framework policies (e.g., competition policy, taxation regimes, intellectual property rights, and the regulatory regime), which may pose barriers to investing in R&D and innovation.

The Committee has made a recommendation to improve the Scientific Research and Experimental Development Tax Incentive Program (see "Taxation Policy"), which it believes will lead to increased spending on R&D by the private sector.

2. Improving Canada's Commercialization Performance

As well as the relatively low performance and financing of R&D by the business sector, other indicators reflect Canada's poor innovation performance. Canada lags behind its major competitors in terms of the commercialization of knowledge and discoveries (i.e., the end use of ideas through the implementation or sale of new goods or services). Recent surveys suggest that the commercialization of Canadian university research has improved over the last few years. For example, between 2003 and 2004, the number of inventions reported or disclosed by researchers to universities and hospitals increased from 1,133 to 1,432 (26%). The number of patents issued to these institutions also increased from 347 to 397 (14%) while the total number of patents held rose from 3,047 to 3,827 (26%).[63] Additionally, more institutions are doing intellectual property (IP) management, and spending more money doing so than in the past.

Despite this increase, there are still problems on both the higher education and private sector sides of the "commercialization gap." For example, according to recent surveys cited by the Expert Panel on Commercialization, most Canadian businesses prefer strategies based on cost containment rather than innovation. In 2001, fewer than 40% of businesses in Canada considered developing new products or production techniques as being important to their business strategies. More than half, however, believed that reducing labour and other operating costs was important.

A. Report of the Expert Panel on Commercialization

In April 2006, the Expert Panel on Commercialization released its report, which contained 11 recommendations intended to improve Canada's commercialization performance (see Appendix C). The Panel suggested that Canada faces a significant challenge in the low level of commitment by many Canadian businesses towards research and the many other components of innovation, especially in comparison to these levels of commitment among Canada's major competitors. It suggested that these failings do much to explain Canada's relatively weak commercialization performance. The Committee believes that the recommendations made by the Panel are important and could boost Canada's commercialization performance. The Committee therefore recommends:

That the Government of Canada seriously consider the recommendations of the Expert Panel on Commercialization and report back to Parliament on its intentions with respect to implementing any or all of them, and/or on other policies it intends to implement to improve Canada's commercialization performance.

B. Bridging the Commercialization Gap

In terms of commercialization, the Committee heard about the difficulty in going from an idea to a product in the marketplace. Witnesses pointed out that Canada does very well at making new discoveries and expanding knowledge, but is relatively bad at making the follow-up investments in order to translate these discoveries into economic returns. The commercialization gap between research and the marketplace has been referred to as the "Valley of Death." At this stage, public money begins to pull out because the returns can be increasingly appropriated by private interests, but private interests are not yet fully committed (or may not be at all) because the risks associated with commercialization can be relatively high.

The Committee heard from/of "fourth-pillar" organizations (e.g., Precarn Incorporated) that are usually independent, non-profit entities funded jointly by government and the private sector that bring together business, government and post-secondary education institutions to focus on the development and commercialization of new technologies. The Committee was impressed with the work of these types of organizations and the important work they are doing to bridge the commercialization gap. The Committee therefore recommends:

That the Government of Canada provide increased funding for organizations that bring together business, government and post-secondary education institutions to focus on the development and commercialization of new technologies.

C. Technology Partnerships Canada

There are federal government programs that help Canadian companies performing R&D take new technologies closer to the marketplace. For example, Technology Partnerships Canada (TPC) is a special operating agency of Industry Canada with a mandate to provide financial support (via conditionally repayable contributions) for strategic research and development, and demonstration projects that will produce economic, social and environmental benefits to Canadians. TPC focuses on key technology areas such as environmental and enabling technologies, which includes biotechnology and health-related applications, plus aerospace and defence technologies as well as manufacturing and communications technologies. TPC support is provided via two main programs: (1) The TPC R&D investment program targets pre-competitive projects across a wide spectrum of technological development; and (2) the TPC IRAP program, delivered by the National Research Council's Industrial Research Assistance Program, which provides support to small to medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) with projects valued under $3 million.

The Committee heard from witnesses, particularly in the automobile and aerospace industries, who have relied heavily on TPC support for R&D and technology development. In September 2005, the previous government announced that TPC would be terminated, and replaced with another initiative to stimulate private sector technology development. In September 2006, the current government announced cuts to TPC's funding. The terms and conditions for the TPC program expired on 31 December 2006, and no new outlines are being accepted and no new projects will be contracted under this program. Given the importance of TPC to certain manufacturing industries the Committee recommends:

That the Government of Canada identify, as soon as possible, a replacement program or alternative funding mechanism for Technology Partnerships Canada in order to support strategic R&D and demonstration projects by industry that are intended to produce economic, social and environmental benefits for Canadians.

D. Networks of Centres of Excellence Program

The Networks of Centres of Excellence (NCE) is a federal program that fosters partnerships among universities, industry, government and not-for-profit organizations that are aimed at turning Canadian research and entrepreneurial talent into economic and social benefits for Canada. The Committee heard from a representative from one of the NCEs (AUTO21) who questioned the value of the program's "sunset clause," whereby a network has a maximum lifespan of 14 years, regardless of whether it is providing value for money.

The Committee believes that the NCE program is a valuable component of Canada's innovation system, and that certain NCEs are of direct importance to the manufacturing sector. The Committee is concerned about relatively flat funding levels (about $80 million per year since 1999) to the program, and the necessity of the 14-year sunset clause. As such, the Committee recommends:

That the Government of Canada conduct a review of the funding levels and operation of the Networks of Centres of Excellence program, and eliminate the automatic 14-year sunset clause that restricts the lifespan of an individual network.

3. Research Infrastructure

The Canada Foundation for Innovation (CFI) was established by the federal government in 1997 with a mandate to invest in research infrastructure to increase the capacity of Canadian universities, colleges, research hospitals, and non-profit research institutions to compete internationally and enhance research productivity. The CFI normally funds up to 40% of a project's infrastructure costs and eligible institutions and their funding partners from the public, private, and voluntary sectors provide the remainder. Based on this formula, the total capital investment by the CFI, the research institutions, and their partners, will exceed $11 billion by 2010. The CFI has a fixed budget of $3.65 billion, and its research programs will end in 2010.

In terms of support to industry, CFI enhances the capacity of Canada's research enterprise by providing state-of-the-art infrastructure required for the training of highly qualified personnel and by promoting the development of technology clusters through collaborations between public research institutions and the private sector.

The Committee believes that modern research infrastructure is important to all stakeholders in Canada's innovation system, including the private sector, and that continued federal support for research infrastructure is essential. The Committee therefore recommends:

That the Government of Canada continue to fund research infrastructure through the Canada Foundation for Innovation on a cost-sharing basis.

[30] The M1 monetary aggregate is defined as currency in circulation plus demand deposits.

[31] The Bank Rate is the rate of interest that the Bank of Canada charges on short-term loans to financial institutions.

[32] The Bank of Canada sets a 50 basis-point target band (i.e., ½ of one percentage point) for the market rate for overnight transactions. The Bank Rate is placed at the upper end of this band and the rate the Bank of Canada pays on settlement balances held by participating financial institutions is placed at the bottom end of this band. The Overnight Rate is set at the midpoint.

[33] Bank of Canada scheduled interest rate announcements are at 9 a.m. on either a Tuesday or Wednesday of:

| January week 3 | July week 2 | |

| March week 1 | September week 1 | |

| April week 4 | October week 3 | |

| May week 4 | December week 1 |

The Bank of Canada retains the option of taking action between these scheduled dates in the event of extraordinary circumstances.

[34] As currently planned, the current federal general corporate income tax rate of 21% is scheduled for gradual reduction to 19% by 2010, and possibly to 18.5% by 2011. See Appendix D and Supplementary Opinions for additional information and discussion.

[35] See details under Research, Development and Commercialization Policies.

[36] The Office of Energy Efficiency defines the industrial sector as manufacturing activities, all mining activities, forestry and construction.

[37] Office of Energy Efficiency, The State of

Energy Efficiency in Canada, Report 2005, Natural Resources Canada

http://oee.rncan.gc.ca/corporate/statistics/neud/dpa/data_e/see05/SEE05.pdf.

[38] Statistics from the Energy Dialogue Group.

[39] Presentation to Committee by Dr. Michael Raymont, EnergyINet, 2 November 2006.

[40] National Advisory Panel on Sustainable Energy Science and Technology, Powerful Connections: Priorities and Directions in Energy Science and Technology in Canada, October 2006, http://www.nrcan.gc.ca/eps/oerd-brde/report-rapport/toc_e.htm.

[41] Statistics Canada, 2001 Census analysis

series: The changing profile of Canada's labour force, 2003,

http://www12.statcan.ca/english/census01/Products/Analytic/companion/paid/pdf/96F0030XIE2001009.pdf.

[42] Statistics Canada, "Fact sheet on retirement," Perspectives

on Labour and Income, Statistics Canada, September 2003,

http://www.statcan.ca/english/freepub/75-001-XIE/comm/2005_04.pdf.

[43] Statistics Canada, 2001 Census analysis series: The changing profile of Canada's labour force, 2003.

[44] Discouraged job seekers are omitted.

[45] Poll conducted by the Environics Research Group for the Public Policy Forum, November 2004.

[46] On 8 December 2006, Ontario was added to the list of regions that are permitted to participate in the program.

[47] As part of China's accession to the WTO in November 2001, China became a party to the Agreement on Textiles and Clothing. Under this agreement, all WTO members agreed to the termination of quotas on textiles by 31 December 2004. However, there is a safeguard mechanism in place until the end of 2008 that permits WTO Member Governments to take action to curb imports in case of market disruptions caused by Chinese exports of textile products. Furthermore, for a 12-year period starting from the date of accession, there will be a special transitional safeguard mechanism in cases where imports of products of Chinese origin cause or threaten to cause market disruption to the domestic producers of other WTO members.

[48] A counterfeit item is an unauthorized representation of a registered trademark carried on goods identical or similar to goods for which the trademark is registered, with a view to deceiving the purchaser into believing that he/she is buying the original goods. OECD definition.

[49] OECD, The Economic Impact of Counterfeiting, 1998, http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/11/11/2090589.pdf.

[50] Canadian Manufacturers & Exporters (CME),

Position Paper – Intellectual Property Rights in Canada and Abroad, June 2006,

http://www.cme-mec.ca/pdf/CME_IPR0606.pdf.

[51] USTR 301 Watch List, 2006, http://www.ustr.gov/assets/Document_Library/Reports_Publications/2005/2005_Special_301/asset_upload_file662_7650.pdf.

[52] On 18 October 2006, the Government of Canada published Regulations Amending the Food and Drug Regulations. One of the amendments was to increase the market exclusivity (i.e., data protection) period for pharmaceutical products from five to eight years.

[53] Brian Isaac and Carol Osmond, The Need for Legal Reform in Canada to Address Intellectual Property Crime, January 2006, http://www.cacn.ca/PDF/CACN%20Position%20Paper%20January%202006%20Clean.pdf.

[54] CFIB, Prosperity Restricted by Red Tape, 2005, http://www.cfib.ca/research/reports/RatedR.pdf.

[55] Canadian Manufacturers and Exporters, 2005-2006 Management Issues Survey,

http://www.cme-mec.ca/pdf/SURVEY%20FINAL.pdf.

[56] Government of Canada, Advantage Canada: Building A Strong Economy for Canadians, November 2006, p. 69, http://www.fin.gc.ca/ec2006/pdf/plane.pdf.

[57] Rethinking our Borders: A New North American

Partnership, Coalition for Secure and Trade-Efficient Borders – July 2005,

http://www.cme-mec.ca/pdf/Coalition_Report0705_Final.pdf.

[58] Statistics Canada, Industrial Research and

Development, 2002 to 2006, Science Statistics, August 2006,

http://www.statcan.ca/english/freepub/88-001-XIE/88-001-XIE2006004.pdf.

[59] OECD, OECD Science, Technology and Industry Outlook, 2006

[60] OECD Science, Technology and Industry Scoreboard 2005.

[61] StatLink: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/130812203177.

[62] Although foreign subsidiaries do access technology

from their parent and sister companies, research conducted in 2000 shows that foreign-owned firms in

Canada are more active in R&D than the population of Canadian-owned firms. They are also more often

involved in R&D collaboration projects both abroad and in Canada. See John Baldwin and Petr Hanel,

(2000) Multinationals and the Canadian Innovation Process, Statistics Canada,

http://www.statcan.ca/english/research/11F0019MIE/11F0019MIE2000151.pdf

[63] Cathy Read, Survey of Intellectual Property

Commercialization in the Higher Education Sector, 2004, Statistics Canada, October 2006,

http://www.statcan.ca/english/research/88F0006XIE/88F0006XIE2006011.pdf.