Legislative Process

Introduction

Law-making is one of the most significant responsibilities of Parliament. As such, the legislative process takes up a significant portion of Parliament’s time. The legislative stages described here are the culmination of a much longer process that starts with the proposal, formulation and drafting of a bill.

In the case of government bills, the Department of Justice drafts the bill following instructions given by cabinet.

Members of the House of Commons who are not in cabinet and are not parliamentary secretaries may introduce bills that could be considered under Private Members’ Business. A private member’s bill is typically drafted on behalf of a member of Parliament by a legislative counsel employed by the House.

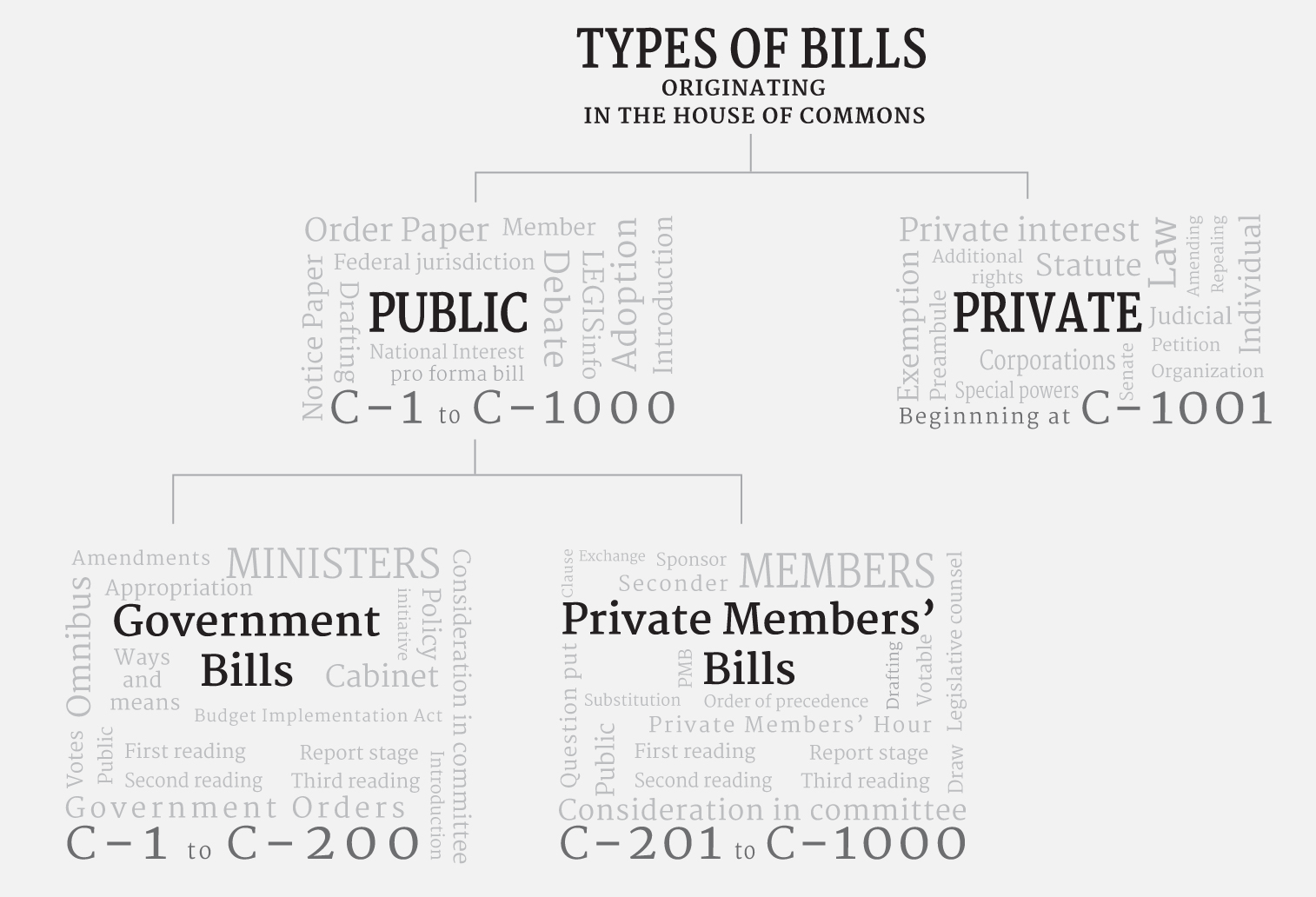

Types of Bills

There are two main categories of bills: public bills and private bills. Public bills deal with matters of national interest, while the purpose of private bills is to grant special powers, benefits or exemptions to a person or persons, including corporations. Most bills considered by the House of Commons are public bills.

A public bill may be initiated by a minister, in which case it is referred to as a “government bill,” or by a private member, in which case it is called a “private member’s bill.”

Stages in the Legislative Process

In our parliamentary system, a bill must go through several specific stages before it becomes law. The stages for a bill originating in the House of Commons are:

Notice and placement on the Order Paper

Introduction and first reading

Second reading and referral to a committee

The second reading stage of the legislative process provides an opportunity to participate in debate on the general scope and principle of the bill.

Once the bill is adopted at second reading, it is referred to committee for further scrutiny.

The role of the committee is to review the text of the bill and to approve or modify it.

Committees may invite witnesses to appear, present their views and answer questions.

Afterwards, the committee proceeds to clause-by-clause consideration of the bill, at which point members may propose amendments.

Once all the clauses of the bill have been considered and adopted with or without amendment, the committee votes on the bill as a whole and the Chair reports the bill to the House.

Report stage allows members to propose motions to amend the text of the bill.

Debate at report stage occurs only when amendments are proposed. The debate focuses on these amendments rather than on the bill as a whole.

The Speaker selects and groups amendments for debate, ensuring that report stage is not a repetition of the consideration in committee.

While no debate will take place at report stage if no amendments were proposed, a vote may be requested for the adoption of the report.

Consideration and passage by the Senate

The Senate follows a legislative process very similar to the one in the House of Commons.

The Senate may also suggest amendments to the bill. If so, both Houses must agree on the same version of the bill before it can receive royal assent.

In cases where the Senate adopts a bill without amendment, a message is sent to the House of Commons and the bill receives royal assent thereafter.

A bill can become law only once the same text has been approved by both Houses of Parliament and has received royal assent.

Most public bills are first introduced in the House of Commons. However, bills may also be introduced in the Senate first, before being studied by the House of Commons.

However, there is a constitutional requirement that bills involving the spending of public funds or relating to taxation be introduced in the House of Commons first. Bills proposing the expenditure of public funds must be accompanied by a royal recommendation, which can only be obtained from the government and presented by a minister. A private member may introduce a public bill containing provisions requiring the expenditure of public funds, provided that a royal recommendation is obtained by a minister before the third reading vote and the passage of the bill.

The Standing Orders of the House of Commons require that each of the three readings of a bill take place on a different day. However, it is possible for a bill to pass several stages in one sitting when there is unanimous consent from all parties.

A member or a minister who intends to introduce a public bill in the House of Commons must first give 48-hours’ written notice to the Clerk of the House. The title of the bill to be introduced is then placed on the Notice Paper.

The day after it appears on the Notice Paper, the title of the bill will appear in the Order Paper, making it ready for introduction in the House.

There are special rules dealing with the introduction of bills that involve the raising or the expenditure of public funds.

Once the notice period has passed, the member or minister seeks leave to introduce his or her bill when the item Introduction of Government Bills or Introduction of Private Members' Bills is called during Routine Proceedings.

A member normally provides a brief summary of the bill he or she is introducing. A minister rarely provides any explanation when requesting leave to introduce a bill but on occasion this is done under Statements by Ministers during Routine Proceedings.

The second reading stage of the legislative process gives members an opportunity to debate the general scope and the principle of the bill. Accordingly, the text of the bill may not be amended during debate at this stage.

However, the motion for second reading may be amended. Three types of amendments are permitted:

- a three months’ or six months’ hoist, which seeks to postpone consideration of the bill for three or six months (and which adoption is equivalent to defeating the bill by postponing its consideration and removing it from the Order Paper);

- a reasoned amendment, which requests that the House not give second reading to a bill for a specific reason; or

- a motion to refer the subject matter of the bill to a committee.

A minister may move that a government bill be referred to a committee before second reading. Doing so allows members of a committee to examine the principle of a bill before it is approved by the House of Commons and to propose amendments to alter its scope.

After the committee reports the bill to the House, the next stage is essentially a combination of the report stage and second reading. Members may propose amendments.

Once agreed to at report stage and read a second time, the bill is ready for third reading.

Most bills are referred to the standing committee the mandate of which most closely corresponds to the bill’s subject matter. However, the House may also choose to refer a bill to a legislative committee, a distinct type of committee created solely to undertake the consideration of legislation.

The role of the committee—standing or legislative—is to review the text of the bill and to approve or modify it. It is at this stage that the minister or member sponsoring the bill, as well as witnesses, may be invited to appear before the committee to present their views and answer members’ questions.

Once the witnesses have been heard, the committee proceeds to clause-by-clause study of the bill. It is at this point that each clause is considered separately and members may propose amendments. Once all the clauses of the bill have been considered and adopted with or without amendment, the committee votes on the bill as a whole.

Once the bill is adopted, the chair asks the committee for leave to report the bill to the House.

Following consideration in committee, there is an opportunity for further study of the bill in the House during report stage. Members may, at this stage, propose motions to amend the text of the bill as it was reported by the committee. The debate focuses on the amendments and not on the bill as a whole.

The Speaker has the power to select and to group amendments for debate and will not normally select amendments that were considered or that could have been considered in committee or amendments that were ruled inadmissible by the committee chair. An amendment requiring a royal recommendation may be selected if it is accompanied by the recommendation. At this stage, an amendment aimed at deleting a clause is admissible. The Speaker also determines whether each motion should be voted on separately or as part of a group.

When deliberations at report stage are concluded, the House proceeds to a vote on the adoption of the amendments according to the grouping set by the Speaker, after which a motion is put forward to concur in the bill at report stage in its entirety.

If no amendments are proposed at report stage:

- there is no debate;

- the House decides whether to concur in the bill at report stage; and

- the motion for third reading and adoption of the bill may be proposed on the same day.

Third reading is the final stage a bill must pass in the House of Commons. It is at this point that members must decide whether the bill will be adopted.

Debate at this stage of the legislative process focuses on the final form of the bill. The amendments that are admissible at this stage are the same as those at second reading stage. An amendment to recommit the bill to a committee with instructions to reconsider certain clauses is also acceptable.

Once the motion for third reading has been adopted, the Clerk of the House certifies that the bill has passed, and the bill is then sent to the Senate with a message requesting that it consider the bill.

The Senate follows a similar legislative process to the one in the House of Commons.

In cases where the Senate adopts a Commons bill without amendment, a message is sent to the House of Commons to inform it that the bill has been passed, and royal assent is normally granted shortly thereafter.

If, however, the Senate makes amendments to a bill, it sends a message to the House with the text of the amendments. If the House does not agree with the Senate amendments, it adopts a motion stating the reasons for its disagreement, which it communicates in a message to the Senate. If the Senate wishes the amendments to stand nonetheless, it sends a message back to the House, which then accepts or rejects the proposed changes (in practice, most times the Senate will accept the decision of the House). If an agreement cannot be reached by exchanging messages, the House that has possession of the bill may ask that a conference be held, although this practice has fallen into disuse.

The ceremony of royal assent is one of the oldest of all parliamentary proceedings and brings together all three constituent parts of Parliament: the Crown, the Senate and the House of Commons. Royal assent is the stage that a bill must pass before officially becoming an act of Parliament. A bill will not be given royal assent unless it has gone through all the stages of the legislative process and has been passed by both Houses in identical form.

Royal assent may be granted in one of two ways: written declaration procedure or the traditional royal assent ceremony.

The written declaration procedure involves the Clerk of the Parliaments—the Clerk of the Senate—meeting with the Governor General to present the bills with a letter indicating that they have been passed by both Houses and requesting that the bills be assented to. At the government’s request, a representative from the Privy Council Office is also present for the signing of written declaration of royal assent, as is a House table officer in the case of a supply bill. Letters advising that royal assent has been signified are delivered without delay to the Speakers of both Houses by the Clerk of the Senate. The custom is for letters about royal assent to be read in the Senate before being read in the House, unless they are received during an adjournment, in which case the message is printed in the Journals for that day. An act that has been given royal assent in written form is considered assented to on the day on which the two Houses of Parliament are notified of the declaration.

If royal assent is granted as part of a formal ceremony, it takes place in the Senate chamber. Members of the Governor General’s staff inform the Speaker of the House of the date and time at which the Governor General—or his or her deputy—will attend the Senate to grant royal assent to bills, and the Speaker relays the message to members of Parliament.

At the set date and time, the Usher of the Black Rod, an officer of the Senate, proceeds to the House of Commons chamber to inform the Speaker that the Governor General desires the immediate presence of the House in the Senate chamber. The Usher then leads the House to the Senate followed, in order, by the Sergeant-at-Arms bearing the mace, the Speaker, the Clerk and table officers, and the members. Once in the Senate chamber, the Speaker and the members gather at the bar and the Usher walks toward the far end of the chamber, bows to the Governor General and calls for order. The Speaker of the House raises their hat and bows to the Governor General, a clerk at the table in the Senate chamber reads—in English and French—the titles of the bills that are to receive royal assent, except for supply bills, and the Clerk of the Senate displays the bills and declares the granting of royal assent.

If there is a supply bill to be assented to, the Speaker of the House of Commons brings it into the Senate chamber, reads a message asking that it be given royal assent, and hands it over to a Senate clerk at the Table, who reads the title of the bill in both official languages and the declaration of royal assent.

The Governor General consents to the enactment of the bills by nodding their head, and the Usher of the Black Rod turns to face the main doors of the Senate chamber, indicating that the ceremony has concluded. The Speaker of the House then raises their hat, bows to the representative of the Crown, and withdraws from the chamber, returning directly to the Commons chamber, where they take the Chair and inform members that royal assent was given to certain bills and the House resumes the business that was interrupted or adjourns if the hour for adjournment has already passed.

Once a bill has been granted royal assent, it becomes law and comes into force either on that date or at a date provided for within the act or specified by an order of the Governor in Council.

Videos on the Legislative Process

For More Information:

- House of Commons Procedure and Practice, third edition, 2017

- Standing Orders of the House of Commons

- Amending Bills at Committee and Report Stages, House of Commons

- LEGISinfo, Parliament of Canada