RNNR Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

INTERNATIONAL BEST PRACTICES FOR INDIGENOUS ENGAGEMENT IN MAJOR ENERGY PROJECTS

Introduction

On 6 December 2018, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Natural Resources (the committee) agreed to undertake a study on international best practices for engaging Indigenous communities in major energy projects, including, but not limited to:

early engagement, mutual benefit agreements or similar contracts, accommodation measures, opportunities for Indigenous business as well as direct employment, outcomes for Indigenous communities after a project completes its lifecycle as well as, general challenges other countries have faced in their relationship with Indigenous peoples and how those countries addressed or solved those challenges…

Over the course of 10 meetings, the committee heard from a wide range of international and Canadian experts, including representatives from Indigenous and non-Indigenous governments, businesses, academic institutions and nongovernmental organizations. This report presents the committee’s study findings and recommendations to the Government of Canada.

The Government of Canada has a duty to consult and, where appropriate, accommodate First Nations, Inuit and Métis when it considers conduct that might adversely impact potential or established Aboriginal or treaty rights.[1] Furthermore, in its Principles respecting the Government of Canada's relationship with Indigenous peoples, Canada acknowledges its commitments to “a renewed nation-to-nation, government-to-government and Inuit-Crown relationship that builds on and goes beyond the legal duty to consult.”[2] Mr. Christopher Duschenes of the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development highlighted principles 4-6, in which the federal government recognizes the following:

- that Indigenous self-government is part of Canada's evolving system of co-operative federalism and distinct orders of government;

- that treaties, agreements and other constructive arrangements between Indigenous people and the Crown have been or are intended to be acts of reconciliation based on mutual recognition and respect;

- that meaningful engagement with Indigenous peoples aims to secure their free, prior, and informed consent when Canada proposes to take actions which impact them and their rights, including their lands, territories and resources.

Canada is also a “full supporter, without qualification,” of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), which offers guidance on cooperative Indigenous relations “in accordance with the principles of justice, democracy, respect for human rights, equality, non-discrimination, good governance and good faith.” Article 32 of UNDRIP calls on UN member states to “consult and cooperate in good faith” with the Indigenous peoples concerned with the aim of obtaining “their free and informed consent prior to the approval of any project affecting their lands or territories and other resources, particularly in connection with the development, utilization or exploitation of mineral, water or other resources.”[3]

While witnesses made it clear that free, prior and informed consent (FPIC) does not grant veto power to Indigenous peoples, the committee heard that the UN principle is protected by two international human right standards: 1) that “all peoples have the right to self-determination,” and 2) that “all peoples have the right to freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development.”[4] According to Dr. Dalee Sambo Dorough, appearing as an individual, “FPIC entails negotiation, dialogue, partnership, consultation and co-operation between the parties concerned, in good faith, [and] with the objective of achieving consent.” She added that states must recognize that human rights are not absolute: “there’s a constant tension between the rights and interests of Indigenous peoples and all others. In some cases, this constant tension is manifested amongst and between the Indigenous peoples concerned.”

This report presents evidence along a spectrum of Indigenous engagement practices, many of which are complimentary and interdependent (Figure 1). The first section discusses Indigenous consultation practices with the intent of securing FPIC. The second section addresses Indigenous partnership beyond the Crown’s duty to consult. Finally, the third section highlights Indigenous-led development as the preferred model for First Nations, Inuit and Métis engagement in energy resource development.

Figure 1: A Spectrum of Indigenous Engagement in Energy Resource Development

Considering the rich diversity of First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities, the committee acknowledges that the evidence outlined herein may not represent the priorities of all Indigenous peoples in Canada. Best practices should be determined on a case-by-case basis, in collaboration with Indigenous governments and communities. This report is presented in good faith, with the intent of strengthening Indigenous engagement and partnerships in the Canadian energy sector.

1. Consultation: Foundations for Consensus-Building

The Crown has a duty to consult and, where appropriate, accommodate First Nations, Inuit and Métis when it considers conduct that might adversely impact potential or established Aboriginal or treaty rights. As Mr. Duschenes explained, this duty “stems from the honour of the Crown and is derived from section 35 of Canada's Constitution Act, 1982, which recognizes and affirms Aboriginal and treaty rights.” The duty to consult was affirmed by the Supreme Court of Canada in several decisions, including Haida, Taku River, Mikisew Cree, Little Salmon/Carmacks and Rio Tinto.[5]

The following subsections outline best practices, according to witnesses, for Indigenous consultation on major energy projects, with the aim of securing FPIC.

a) Early and Ongoing Engagement

Witnesses agree that early and ongoing engagement is necessary to build long-term, constructive relationships between project proponents and Indigenous peoples.[6] In the words of Mr. Grant Sullivan of Gwich’in Council International: “In order to succeed, energy projects need to start with and be driven by the community. This helps ensure that projects are planned in a manner that aligns with the community's interests and needs.” Similarly, Mr. Duane Ningaqsiq Smith of the Inuvialuit Regional Corporation stated that “early consultation with rights holders facilitates common understanding of impacts on rights under a land claim agreement and alignment of mutual interests, such as the need for energy security and reduction of emissions.” He advises industry proponents to think of the time allocated to achieving FPIC as “an investment in a project’s success.”

BEST PRACTICES

Witnesses highlighted the following best practices for the early and ongoing consultation of First Nations, Inuit and Métis on major energy projects:

- Engaging local governments and communities as early as possible, preferably at the project conceptualization or design phase.[7] According to Professor Brenda Gunn of the University of Manitoba, this practice is consistent with the international standard for FPIC, intended to allow affected communities to “truly participate in the decision-making and have an impact on the outcome.” Furthermore, Ms. Tracy Sletto of the National Energy Board and Mr. Robert Beamish of Anokasan Capital pointed out that early and informal resolution of issues is preferable to more formal, and often lengthier, adjudication processes.

- Continuing to engage throughout the full life-cycle of the project, with the intent of building trust, maintaining local support and addressing new or lingering concerns.[8] Witnesses advise industry proponents to negotiate mutually beneficial agreements that cover the full life-cycle of energy projects, some of which span several decades, making sure to allocate enough time, budget and management resources to ensure ongoing input from affected communities. According to Ms. Sletto, full life-cycle engagement leads to better regulation, “including enhanced safety and environmental protection outcomes.”

- Creating (or updating) regional industrial development protocols that facilitate early engagement.[9] As Chief Bill Erasmus of the Arctic Athabaskan Council explained, these protocols can provide more clarity on how to conduct consultations in line with community laws and customs. Furthermore, they may be used to enhance the consultation capacity of smaller enterprises, some of which may have limited means for early engagement, as pointed out by Professor Dwight Newman of the University of Saskatchewan.

b) Meaningful Dialogue

“Our differences can only bring us together once we understand how they separate us.”

Robert Beamish, Anokasan Capital

The committee heard that consultation with First Nations, Inuit and Métis should be conducted in good faith, yielding outcomes that reflect the values, interests and priorities of local governments, communities and social groups.[10] In the words of Mr. Nils Andreassen of the Alaska Municipal League: “for Indigenous peoples, good practice will feel right if the ultimate decision is values-driven and reflects local feedback … [I]t will be Indigenous peoples who will determine whether an engagement has been meaningful or a [best practice].”

BEST PRACTICES

Witnesses discussed the following best practices for conducting meaningful Indigenous consultations on major energy projects in Canada:

- Approaching affected groups collectively, without preconceived ideas about the outcome of consultations.[11] As Dr. Liza Mack of the Aleut International Association put it, “when you come in with an assumption about what should happen in a community, it turns people off from listening to you and wanting to hear your side.” Chief Bill Erasmus of the Arctic Athabaskan Council advises industry proponents to approach affected groups as a collective in order to facilitate consensus-building: “They all hear the same things. Then they can talk amongst themselves, and they'll develop a way to say yes or no.” In addition, Ms. Rumina Velshi of the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission identified multi‑stakeholder meetings as a best practice for addressing several issues at once.

- Identifying areas of alignment prior to engagement, with good knowledge of the history, culture, treaty rights and socioeconomic priorities of each nation or community.[12] As Mr. Beamish put it, “our differences can only bring us together once we understand how they separate us.” He advises industry proponents to be actively aware of any cultural bias towards Indigenous peoples. Similarly, Ms. Sletto highlighted Indigenous cultural competency training as a best practice, whileChief Isaac Laboucan-Avirom of the Woodland First Nation called for “an educational component for international companies to understand the landscape in Canada so that First Nations don't have to consistently recreate this work.”

- Cultivating a safe and respectful negotiation environment where both positive and negative feedback is encouraged and addressed, free of intimidation, coercion, manipulation, harassment, prejudice and divisiveness.[13] Professor Gunn urges industry proponents to be especially mindful in situations where communities may feel pressured to engage due to economic duress, and ensuring they are “not further dividing the community.” In addition, Professor Ciaran O’Faircheallaigh of Australia’s Griffith University stressed that negotiations should occur in a context in which Indigenous peoples have “real bargaining power,” reasserting the value of FPIC as a legal framework in this regard. Finally, Mr. Andreassen recommends reporting all decisions back with clear explanations of how community input was included: “Indigenous people should see their values reflected within a decision. This is how communities will know that they have been listened to and engaged with meaningfully.”

c) Inclusiveness, Accessibility and Capacity Enhancement

The committee heard that meaningful consultation should engage and address the needs of diverse communities and social groups, including women, children and youth.[14] Moreover, witnesses stressed that engagement processes need to be accessible and feasible for Indigenous participants, thereby enabling the achievement of FPIC.[15] In the words of Chief Laboucan-Avirom, Indigenous people “need to have the capacity to understand the technical aspects of [energy] projects, communicate information to community members, and gather information from community members and knowledge-keepers. This takes much more funding than is currently offered by Canada.”

BEST PRACTICES

Witnesses highlighted the following best practices for improving the inclusiveness and accessibility of Indigenous consultations for diverse social groups:

- Enhancing local decision-making capacity by disseminating community-wide resources that promote energy and business literacy, engaging independent specialists to assist with impact and risk assessments, and providing participant funding and administrative support, where needed.[16] According to Ms. Raylene Whitford of Canative Energy, energy/business literacy entails knowledge of key concepts, processes and terminology about the industry/project. It is a foundation for informed consent. Furthermore, Professor Gunn explained that international law requires the engagement of independent specialists to ensure that Indigenous people “should not have to rely solely on the materials put forward by [industry proponents].” Mr. Chris Karamea Insley, Māori advisor to Canative Energy, urges project managers to ensure their engagements are relevant and accessible to diverse community audiences. He pointed out that the “aunty test” is often the hardest to pass: “one of the aunties will stand up and [ask], ‘Yes, we know all of those [financial] numbers, but what are you going to do to grow our people?’”

- Consulting participants of all genders, ages, physical/mental abilities, education levels and social statuses.[17] According to Mr. Ian Thomson of Oxfam Canada, Indigenous women leaders recognize “an entrenched gender bias in how decisions are made around energy and natural resources.” He and Professor Gunn called for targeted assessments of the impacts of energy projects on women and children, bearing in mind the gender power dynamics in each community. In addition, Ms. Whitford urges industry to engage and empower young Indigenous leaders that “look forward to being heard.”

- Accommodating oral traditional evidence (OTE) and other forms of communication and engagement, based on advice from local experts.[18] As Professor O’Faircheallaigh suggested, Indigenous people tend to favour a broad variety of engagement forms, such as small and one-on-one meetings, or discussions at the site of anticipated project impacts, where they “feel much freer and are much better able to express their understandings.” Witnesses recommend working with Indigenous experts to ensure engagement methods, dates, times and locations are appropriate for local participants.

2. Partnership: Beyond the Duty to Consult

“Partnerships with private industry are the key to the growth of our economies.”

Wallace Fox, Indian Resource Council

Witnesses told the committee that meaningful engagement with First Nations, Inuit and Métis should go beyond the Crown’s duty to consult towards a logic of co-development and business partnership.[19] According to Ms. Naina Sloan of Natural Resources Canada, “joint leadership and co-design offer a more certain path to identifying shared interests and enabling diverse parties to work together.” Indeed, Mr. John Helin, mayor of the Lax Kw’alaams Band, stated the following on behalf of his community:

To enable respectful development, Lax Kw'alaams does not want to be treated merely as another interest-holder in our territories. As title-holder to the lands and territories, Lax Kw'alaams must be a full participant in all processes relating to a proposed project and must also be a beneficiary of that project. This goes beyond engagement and includes consenting to the project. This should include: compliance with overall land and resource plans; co-operative determination of what approvals may be required; actively co-designing and participating in the processes leading to any approvals; and, ongoing involvement in compliance monitoring, including decommissioning of projects.

The following subsections address best practices, according to witnesses, for advancing energy co-development and business partnership with Indigenous governments and communities.

a) The Application of Indigenous Knowledge

Based on the work of the permanent members of the Arctic Council, Dr. Ellen Inga Turi of the Sámi University of Applied Sciences defines Indigenous knowledge as follows:

[A] systematic way of thinking and knowing that is elaborated and applied to phenomena across biological, physical, cultural and linguistic systems. [Indigenous] knowledge is owned by the holders of that knowledge, often collectively, and is uniquely expressed and transmitted through Indigenous languages. It is a body of knowledge generated through cultural practices, lived experiences including extensive and multi-generational observations, lessons and skills. It has been developed and verified over millennia and is still developing in a living process, including knowledge acquired today and in the future, and it is passed on from generation to generation.[20]

The committee heard that Indigenous knowledge is often overlooked or underused in the resource development sector.[21] According to Professor O’Faircheallaigh, “there tends to be a deeply in-built assumption that western science offers the only valid understanding of environmental processes and outcomes.” He added that even when Indigenous knowledge is used, “it tends to be co-opted and presented in a frame that's very much dominated by western assumptions and western values.”

BEST PRACTICES

Witnesses highlighted the following best practices for the application of Indigenous knowledge in energy projects:

- Incorporating Indigenous knowledge, expertise and best practices in the development, design and implementation of project-related policies, consultations, monitoring activities, and risk assessment and management strategies.[22] According to research by Dr. Turi, Indigenous knowledge should be applied at the policy development stage; “waiting until policy implementation to include it will be more challenging, if not downright impossible.” Moreover, Dr. Steve Hemming of Australia’s Flinders University advises industry to incorporate Indigenous values in risk management at all levels: “if an Indigenous nation has a process of risk management or risk assessment of [an] action, then there's a way forward for identifying what needs to take place in a strategic way.”

- Conducting Indigenous-led impact assessments – preferably in Indigenous languages – that take into account local socioeconomic and cultural priorities, not just environmental impacts.[23] As Professor O’Faircheallaigh pointed out, Indigenous-led assessments are “much more capable of properly identifying the key issues for Indigenous people and, just as importantly, of identifying viable strategies for dealing with those impacts.” Dr. Turi further stated that Indigenous knowledge is “rooted in Indigenous languages,” affirming that conducting impact assessments by Indigenous researchers in their own language would be a step in the right direction.

- Fostering information alignment and knowledge co-production between Indigenous peoples and non-Indigenous stakeholders.[24] While Indigenous and western practices may sometimes be at odds, Professor Hans-Kristian Hernes of the Arctic University of Norway indicated that patient and meaningful dialogue tends to lead to constructive outcomes and mutual understanding. Dr. Mack urges industry proponents to remain open-minded about the ways First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities work, keeping in mind that “western approaches to research and collecting information could be different from what they are used to.” Ms. Whitford advises project managers to consider Indigenous communities “as an operator would consider their joint venture partner.”

b) Sustainable and Equitable Development

“Reconciliation should begin with economic empowerment.”

Dawn Madahbee Leach, National Indigenous Economic Development Board

UNDRIP recognizes that “respect for Indigenous knowledge, cultures and traditional practices contributes to sustainable and equitable development and proper management of the environment.” According to witnesses, sustainable development should include both environmental stewardship and socioeconomic benefits for local communities – namely, opportunities for long-term employment, professional education/training, and other social, economic and cultural gains.[25]

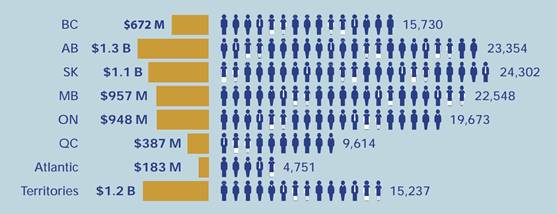

The committee heard that the benefits of Indigenous socioeconomic development extend to all Canadians. According to a 2016 study by the National Indigenous Economic Development Board (NIEDB), closing the productivity gap between Indigenous and non‑Indigenous people in Canada would lead to “an estimated increase in GDP of $27.7 billion annually, or about a 1.5% boost to the nation’s economy.” Ms. Dawn Madahbee Leach of NIEDB told the committee that such economic outcomes could be achieved if Indigenous people – “the most marginalized [group] in Canada” – were to have the same levels of education and employment as the average population (Figures 2 and 3). In this respect, she stated that “reconciliation should begin with economic empowerment.”[26]

Figure 2: Increasing Indigenous Employment Opportunities and Participation

If Indigenous peoples currently with employment income had the same education and training as non-Indigenous people, then the productivity of Indigenous labour would match the productivity of non-Indigenous labour. The average employment income among Indigenous people would then rise to match that of non-Indigenous Canadians. Closing the education and training gaps would result in an additional $8.5 billion in income earned annually by the estimated Indigenous workforce.

Source: National Indigenous Economic Development Board (November 2016).

Figure 3: Increasing Indigenous Employment Opportunities and Participation

If Indigenous peoples are given the same access to economic opportunities available to other Canadians (i.e., access to new jobs, equal conditions of employment, possibility to start a business), they will be more likely to fully participate in the labour force. Matching economic outcomes by increasing the Indigenous employment rate would result in an estimated $6.9 billion annually in additional employment income among 135,210 newly employed Indigenous peoples.

Source: National Indigenous Economic Development Board (November 2016).

The committee heard that sustainable and equitable development can be the product of Indigenous-industry partnerships, such as impact benefit agreements (IBAs), equity partnerships and joint ventures.[27] Professor Newman explained that some IBAs have brought significant benefits to Indigenous communities, “particularly when they have included strong provisions supporting business development that outlasts a particular non-renewable resource or that builds from the base of an existing renewable resource.” Furthermore, Mr. Ian Jacobsen of Ontario Power Generation (OPG) affirmed that OPG’s equity partnerships with First Nations have been mutually beneficial and “can be excellent models for reconciliation.”

The committee also heard of exemplary joint ventures involving Indigenous-led businesses in the energy sector. Tarquti Energy Corporation is leading the long-term development of renewable energy in Nunavik (northern Quebec), while Onion Lake Energy (OLE), Frog Lake Energy Resources Corp. and the Fort McKay Group of Companies have built successful partnerships in Alberta’s oil and gas industry.[28] Speaking for the Onion Lake Cree Nation, Mr. Wallace Fox of the Indian Resource Council (IRC) described the joint venture between OLE and Calgary-based BlackPearl Resources as a “success story.” He stated the following:

In my tenure as chief, we took this revenue from the royalties, from the partnerships and from the contracts, creating employment, purchasing a construction company, where people went from getting the social assistance norm of $150 a month to making $2,000 a week driving big machinery. We built roads, lease buildings and lagoons. We invested in a carpentry program. We built 400 to 500 homes with the resources—again, with jobs, drywalling training, for both men and women. We built our own school, our own training centre. We have our own care home. We're also looking at a private hospital now, in Leduc—which is $100 million.

Mr. Fox affirmed that “partnerships with private industry are the key to the growth of [Indigenous] economies.”

BEST PRACTICES

Witnesses discussed the following best practices for fostering sustainable and equitable energy-sector development in Indigenous communities:

- Negotiating mutually beneficial Indigenous-industry agreements that deliver measurable outcomes, including long-term employment, education/skills training, youth scholarships and other socioeconomic, cultural and environmental benefits, as needed.[29] In general, witnesses agree that communities benefit most from long-term opportunities with consistent gains. Mr. Beamish identified employment, equity, environment and education as the “four Es” of sustainable development, explaining that the emphasis given to each will depend on local priorities. Chief Laboucan-Avirom advises industry proponents to work closely with community insiders in order to leverage local talent and identify mutually beneficial business opportunities.

- Establishing procurement policies that support Indigenous-led businesses, goods and services, similar to Australia’s Indigenous Procurement Policy (IPP).[30] The IPP’s purpose is to “leverage the Commonwealth’s annual multi-billion procurement spend to drive demand for Indigenous goods and services, stimulate Indigenous economic development and grow the Indigenous business sector.” According to Ms. Leach, the Australian program has created “more than $1 billion in contracts to more than 1,200 Indigenous businesses.” Dr. Hemming noted that IPPs have been “a major innovation” at both the federal and state levels in Australia.

- Investing in heritage trust funds to ensure that the revenue generated from the development of non-renewable energy resources benefits both current and future generations.[31] Examples of best practices include Alberta’s Heritage Savings Trust Fund, the Alaska Permanent Fund and the Government Pension Fund of Norway (also known as the “Oil Fund”). Professor Greg Poelzer of the University of Saskatchewan likened heritage trust funds to Registered Retirement Savings Plans (RRSPs); they make financial sense despite shorter-term expenses. Furthermore, Ms. Whitford suggested that many Indigenous peoples tend to be long-term planners; government support to co-develop community trust funds would likely be well received.

c) Infrastructure Modernization and Energy Independence

“Clear rights frameworks, mutually respectful relationships and tangible strategic plans for infrastructure development in remote areas are required to control access [to energy resources] and maximize benefits to Canadians.”

Mr. Duane Ningaqsiq Smith, Inuvialuit Regional Corporation

Many Indigenous communities are located in remote areas with limited infrastructure and access to energy resources. According to Professor Poelzer, energy access and security is an ongoing issue for the vast majority of remote and rural communities in the territorial and provincial north: “The high cost of energy often contributes to grinding poverty and the ‘heat or eat’ dilemma in many communities. The lack of stable power is a deterrent to business development and business investment.”

By way of example, Mr. Smith described the Inuvialuit Settlement Region (located in Canada’s western Arctic) as “resource rich but infrastructure poor,” subject to one of the highest energy costs in Canada. He stated the following:

There is a lack of commercial access to the ocean, local energy production facilities, adequate telecommunications … we truck most of our energy needs from thousands of kilometres away, either from British Columbia or Alberta, to fuel the energy in the communities. This doesn't make sense to us when we're sitting on nine trillion cubic feet of gas.… You can imagine the greenhouse gas emissions from that. We are subject, as well, to high transportation surcharges, and there's a limited number of companies that can supply this energy. The region has very limited disposable income among residents and inability to pay more. Residents give up nutritious food, home repairs and opportunities for their kids so that they can pay for heat and power. The energy costs in our region are probably the highest in Canada. There is a real desire to develop local energy resources, but infrastructure, again, is needed.

Witnesses told the committee that the global transition towards a low-carbon energy future presents a unique opportunity to build long-term Indigenous partnerships in remote and rural communities.[32] In the words of Professor Poelzer:

If we think about the national railway of the 19th century as the key infrastructure project that helped to build Canada from sea to sea, I would suggest that the global energy transition offers Canada the same opportunity in the 21st century.… The energy transition can be a nation-building project that includes all founding peoples and contributes to our journey of reconciliation, through steel in the ground.

Chief Byron Louis of the Okanagan Indian Band, who shared the perspective of the Assembly of First Nations (AFN), affirmed that the energy sector is a “much-needed partner” to advance a renewed relationship between Indigenous governments and the Crown, adding that “First Nations are increasingly joining Canada's growing clean energy economy as a way to generate revenue in a manner that is consistent with [their] cultural and environmental values.” Similarly, Mr. Sullivan told the committee that “small, remote northern communities like Inuvik have unique energy needs that provide a strong foundation for pursuing smaller and more sustainable community-based renewable energy developments.” Finally, Mr. Smith stated that natural gas should be “a key component in the global transition from coal and diesel, maximizing local resources while helping reach carbon emission reduction targets.”

BEST PRACTICES

Witnesses highlighted the following priorities for enhancing the infrastructural capacity and energy security of Indigenous communities in remote and rural areas of Canada:

- Supporting the development of transportation and communication infrastructure to enable sustainable resource development in remote and rural areas, especially in the provincial and territorial north.[33] Speaking for the Inuvialuit Settlement Region, Mr. Smith stated that Canada needs to “engage with Indigenous organizations to plan infrastructure investments that will benefit both local residents and the Canadian economy over the next 20 years.” Dr. Dorough suggested that the Arctic Council would be in a good position to facilitate development cooperation among regions of the circumpolar Arctic.

- Encouraging the development of community-owned and operated utilities through public-private partnerships and regional cooperatives.[34] With reference to the business models of Finnmark Kraft in Norway and the Alaska Village Electric Cooperative (AVEC) in the United States,[35] Professor Poelzer explained that the independent production of electric power creates opportunities for equity ownership and new business ventures; sustainable local employment and revenue; and “democratization in decision-making at the local level.” Chief Louis advises governments to focus on promoting energy independence by “[assisting] with the transition away from diesel power generation for approximately 112 diesel-dependent First Nations across Canada.”

- Settling outstanding land claims and, where needed, modernizing existing land claim agreements with the aim of strengthening Canada’s industrial development framework for the benefit of all.[36] As Professor Gunn noted, many land claims are outstanding, and for those that are settled, treaty obligations are not always fulfilled. Furthermore, Mr. Smith suggested that some existing land claim agreements – namely the Inuvialuit Final Agreement – need to be modernized “to reflect the current environmental, legal and geopolitical landscape” in light of growing foreign interest in resource development in northern Canada. He stated that “clear rights frameworks, mutually respectful relationships and tangible strategic plans for infrastructure development in remote areas are required to control access [to energy resources] and maximize benefits to Canadians.”

3. Indigenous-Led Development: The Way Forward

Many of the best practices outlined in the previous sections are complimentary and interdependent. Their underlying objective is to strengthen Indigenous engagement and partnerships in Canada’s energy sector, as part of ongoing efforts to reconcile Indigenous-Crown relations. According to established international human rights standards, First Nations, Inuit and Métis have the right to self-determination. Furthermore, the federal government acknowledges that “their self-government is part of Canada's evolving system of co-operative federalism and distinct orders of government.”[37]

“First Nations are increasingly joining Canada's growing clean energy economy as a way to generate revenue in a manner that is consistent with our cultural and environmental values.”

Chief Byron Louis, Okanagan Indian Band

To this end, the committee heard that Indigenous-led development is the “preferred model” for the development of Indigenous lands and resources, presenting “win-win” opportunities that can bring “alignment between otherwise competing interests.”[38] In the words of Dr. Dorough, “[the] outcomes of Indigenous-initiated and Indigenous-controlled development are bound to be far more responsive to the priorities, interests, concerns, cultural values and rights of Indigenous peoples.” This view is consistent with the UNDRIP conviction that “control by Indigenous peoples over developments affecting them and their lands, territories and resources will enable them to maintain and strengthen their institutions, cultures and traditions, and to promote their development in accordance with their aspirations and needs.”[39]

BEST PRACTICES

The Māori of New Zealand

The committee heard that the Māori people of New Zealand have been leaders in Indigenous economic development and self-determination. Over the past three-to-four decades, the Māori economy grew from approximately $30 to $50 billion NZD, becoming “a cornerstone” of the New Zealander economy. Mr. Insley stated that the Māori economy is growing at a compound annual rate of 15-20%, compared to the country’s average of 2-3%. The committee also heard that Māori culture is fully integrated in mainstream society: there are Māori schools and universities; place names are in Māori, the country’s second official language; and the traditional Māori dance, “the haka,” has become an internationally recognized trademark of New Zealand.[40]

Mr. Insley attributed the economic success and international leadership of the Māori people to several factors, most notably the following:

- Treaty land settlement. New Zealand’s treaty settlement process created a pool of development capital that got reinvested in Māori-owned businesses, thereby stimulating the Māori economy. This initial “settlement redress” also contributed to the vertical integration of management-savvy businesses that now cover production cycles from raw material extraction through to international marketing under the Māori brand.

- Youth education. Over the past two decades, a surge of Māori youth started seeking higher education in New Zealand and overseas, many returning home with valuable skills and expertise. The challenge for Māori communities and the New Zealand government has been to welcome their youth back to sustainable economic opportunities. As Mr. Insley explained, success is “not through a government-driven, top-down approach only; it has to come from communities [and families] to drive that back up.” Māori businesses offer annual youth scholarships for higher education in universities and trades colleges.

- International trade and cooperation. Māori business leaders participate in the development of international trade policy alongside the New Zealander Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade (MFAT). According to Mr. Insley, MFAT recognizes the Māori economy and culture as a “point of difference in trading with other nations.” Moreover, the Māori have developed close partnerships with fellow Indigenous peoples across the globe. They are eager to share their best practices and engage in Indigenous business-to-business trade.

While First Nations, Inuit and Métis still face disproportionate barriers to business development in Canada, as previously noted, witnesses highlighted major advancements in Indigenous education, employment, entrepreneurship and innovation over the past few decades.[41] For example, according to Ms. Leach, studies by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) indicate that the Indigenous business environment in Canada is more favourable than those of other countries, with 58 Indigenous-owned financial institutions, two Indigenous-owned banks, and more than 56,000 Indigenous businesses nationwide. Furthermore, Professor Poelzer told the committee that First Nations businesses have been growing at 8.2% over the last decade, outstripping the growth rates of OECD countries; that their business start-ups are 500% greater than the Canadian mainstream, reflecting a high degree of entrepreneurship. Similarly, Ms. Whitford spoke of a revival of Indigenous entrepreneurship and innovation in Canada, where First Nations, Inuit and Métis are creating “incredible businesses with new ideas.”

The committee heard that First Nations, Inuit and Métis businesses would benefit from measures to enhance their capacity for trade and cooperation with other countries and Indigenous peoples.[42] For example, Ms. Whitford called for “more government support of … international liaising, engagement, discussion [and] communication between Indigenous communities,” while Mr. Beamish suggested that Canadian embassies and consulates would do well to develop more awareness of Indigenous-based opportunities at home. Mr. Fox suggested that the Government of Canada should facilitate economic development partnerships between Indigenous peoples and foreign investors; leverage more Indigenous leadership in international delegations. Furthermore, Professor Poelzer spoke of the “enormous opportunity” to market Indigenous know-how around the world, especially in the renewable energy sector of northern-based economies. He cited the Arctic Remote Energy Network Academy as a model of international energy development cooperation, bringing together “energy champions from Indigenous communities, from everywhere from Greenland to Canada to Alaska.”

While witnesses pointed out that other countries look to Canada for best practices on Indigenous issues, including consultation, engagement, land rights and self-government agreements, they made it clear that Indigenous-Crown relations in our shared energy sector are a work in progress.[43] As Professor Newman put it, “the best practices are probably still ahead of us and are ones to keep seeking,” in partnership with First Nations, Inuit and Métis.

[1] Standing Committee on Natural Resources (RNNR), Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament (Evidence): Mr. Christopher Duschenes (Acting Assistant Deputy Minister, Department of Indigenous Services Canada, Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development [DIAND]); and Mr. Ellis Ross (Member of the Legislative Assembly of British Columbia, Skeena [B.C. MLA]).

[2] RNNR Evidence: Mr. Duschenes (DIAND); and Mr. Sullivan (Gwich’in Council).

[3] RNNR Evidence: Dr. Dalee Sambo Dorough (Senior Scholar, University of Alaska Anchorage, appearing as an individual); Mr. Duschenes (DIAND); Chief Byron Louis (Okanagan Indian Band, Assembly of First Nations [AFN]); Mr. John Helin (Mayor, Laz Kw’alaams Band); and Grant Sullivan (Executive Director, Gwich’in Council International [Gwich’in Council]). Also see: Government of Canada, United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

[4] RNNR Evidence: Mr. Duschenes (DIAND); Dr. Dorough (as an Individual); Chief Bill Erasmus (International Chair, Arctic Athabaskan Council); Mr. Duane Ningaqsiq Smith (Chair and Chief Executive Officer, Inuvialuit Regional Corporation); Chief Byron Louis (AFN); Mr. Helin (Laz Kw’alaams Band); Professor Brenda Gunn (University of Manitoba); and Mr. Ellis Ross (B.C. MLA).

UNDRIP acknowledges that the Charter of the United Nations, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and the Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action “affirm the fundamental importance of the right to self-determination of all peoples, by virtue of which they freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development.”

[5] RNNR Evidence: Mr. Duschenes (DIAND); and Ellis Ross (B.C. MLA).

[6] RNNR Evidence: Mr. Helin (Laz Kw’alaams Band); Mr. Smith (Inuvialuit Regional Corporation); Chief Isaac Laboucan-Avirom (Chief, Woodland Cree First Nation); Mr. Sullivan (Gwich’in Council); Ms. Dawn Madahbee Leach (Vice Chair, National Indigenous Economic Development Board [NIEDB]); Ms. Raylene Whitford (Director, Canadtive Energy); Mr. Robert Beamish (Director, Anokasan Capital); Dr. Liza Mack (Executive Director, Aleut International Association); Craig Benjamin (Campaigner, Indigenous Rights, Amnesty International); Ms. Gunn-Britt Retter (Head, Arctic and Environment Unit, Saami Council); Professor Brenda Gunn (Associate Professor, Faculty of Law, University of Manitoba); Professor Ciaran O’Faircheallaigh (Professor, Griffith University, Australia); Professor Greg Poelzer (Professor, University of Saskatchewan); Mr. Nils Andreassen (Executive Director, Alaska Municipal League); Dr. Steve Hemming (Professor, Flinders University, Australia); Mr. Chris Karamea Insley (Advisor, Canative Energy); Ms. Naina Sloan (Senior Executive Director, Indigenous Partnerships Office - West, Department of Natural Resources [NRCan]); Mr. Duschenes (DIAND); Tracy Sletto (NEB); Ms. Tracy Sletto (Executive Vice-President, Transparency and Strategic Engagement, National Energy Board [NEB]); Mr. Robert Steedman (Chief Environment Officer, NEB); Rumina Velshi (President and Chief Executive Officer, Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission [CNSC]); and Ian Jacobsen (Director, Indigenous Relations, Ontario Power Generation, Canadian Electricity Association [OPG/CEA]).

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] RNNR Evidence: Dr. Liza Mack (Aleut International Association); Chief Erasmus (Arctic Athabaskan Council); and Professor Gunn (University of Manitoba).

[10] RNNR Evidence: Chief Laboucan-Avirom (Woodland First Nation); Mr. Helin (Laz Kw’alaams Band); Mr. Smith (Inuvialuit Regional Corporation); Ms. Sloan (NRCan); Mr. Duschenes (DIAND); Ms. Sletto (NEB); Mr. Steedman (NEB); Ms. Velshi (CNSC); Mr. Jacobsen (OPG/CEA); Mr. Beamish (Anokasan Capital); Dr. Mack (Aleut International Association); Professor Poelzer (University of Saskatchewan); Mr. Benjamin (Amnesty International); Mr. Andreassen (Alaska Municipal League); Dr. Hemming (Flinders University); Ms. Leach (NIEDB); Professor Gunn (University of Manitoba); Professor O’Faircheallaigh (Griffith University); and Mr. Duschenes (DIAND).

[11] RNNR Evidence: Dr. Mack (Aleut International Association); Mr. Ian Thomson (Policy Specialist, Extractive Industries, Oxfam Canada); Professor Dwight Newman (Professor of Law and Canada Research Chair in Indigenous Rights, University of Saskatchewan); Mr. Benjamin (Amnesty International); Professor Gunn (University of Manitoba); Mr. Sullivan (Gwich’in Council); and Mr. Beamish (Anokasan Capital); Mr. Helin (Laz Kw’alaams Band); and Chief Erasmus (Arctic Athabaskan Council).

[12] RNNR Evidence: Mr. Brian Craik (Director, Federal Relations, Grand Council of the Crees [Eeyou Istchee]); Mr. Beamish (Anokasan Capital); Chief Delbert Wapass (Board Member, Indian Resource Council [IRC]); and Mr. Andreassen (Alaska Municipal League).

[13] RNNR Evidence: Professor Gunn (University of Manitoba); Mr. Sullivan (Gwich’in Council); Chief Wapass (IRC); Mr. Andreassen (Alaska Municipal League). Professor O’Faircheallaigh (Griffith University); Mr. Beamish (Anokasan Capital); and Ms. Sletto (NEB).

[14] RNNR Evidence: Professor Newman (University of Saskatchewan); Ms. Whitford (Canative Energy); Dr. Mack: (Aleut International Association); Chief Erasmus (Arctic Athabaskan Council); Mr. Steedman (NEB); Ms. Velshi (CNSC); Mr. Ross (B.C. MLA).

[15] RNNR Evidence: Mr. Helin (Laz Kw’alaams Band); Chief Erasmus (Arctic Athabaskan Council); Dr. Mack (Aleut International Association); Mr. Duschenes (DIAND); Ms. Velshi (CNSC); Professor O’Faircheallaigh (Griffith University); Mr. Andreassen (Alaska Municipal League); Professor Gunn (University of Manitoba); Chief Laboucan-Avirom (Woodland First Nation); and Ms. Leach (NIEDB).

[16] RNNR Evidence: Professor Gunn (University of Manitoba); Ms. Whitford (Canative Energy); Chief Laboucan-Avirom (Woodland First Nation); Mr. Helin (Laz Kw’alaams Band); Chief Erasmus (Arctic Athabaskan Council); Dr. Mack (Aleut International Association); Professor O’Faircheallaigh (Griffith University); and Ms. Leach (NIEDB).

[17] RNNR Evidence: Professor Gunn (University of Manitoba); Mr. Thomson (Oxfam Canada); Ms. Whitford (Canative Energy); Mr. Andreassen (Alaska Municipal League); Ms. Leach (NIEDB); Mr. Beamish (Anokasan Capital); Dr. Mack (Aleut International Association); and Mr. Velshi (CNSC).

[18] RNNR Evidence: Professor Gunn (University of Manitoba); Chief Wapass (Indian Resource Council); Ms. Leach (NIEDB); Mr. Andreassen (Alaska Municipal League); Professor O’Faircheallaigh (Griffith University); Dr. Turi (Sámi University of Applied Sciences); Dr. Mack (Aleut International Association); Mr. Beamish (Anokasan Capital); Mr. Benjamin (Amnesty International); Prof. Greg Poelzer (University of Saskatchewan); Ms. Sloan (NRCan); Ms. Velshi (CNSC); and Ms. Sletto (NEB).

[19] RNNR Evidence: Mr. Fox (IRC); Professor Newman (University of Saskatchewan); Mr. Helin (Laz Kw’alaams Band); Chief Louis (AFN); Mr. Perera (CEA); Chief Louis (AFN); Mr. Duschenes (DIAND); Ms. Velshi (CNSC); Ms. Sletto (NEB); and Mr. Hubbard (CEAA).

[21] RNNR Evidence: Mr. Andreassen (Alaska Municipal League); Professor O’Faircheallaigh (Griffith University); Dr. Hemming (Professor, Flinders University); and Dr. Turi (Sámi University of Applied Sciences).

[22] RNNR Evidence: Dr. Turi (Sámi University of Applied Sciences); Dr. Liza Mack (Aleut International Association); Ms. Sloan (NRCan); Ms. Sletto (NEB); Ms. Velshi (CNSC); Professor Poelzer (University of Saskatchewan); Ms. Leach (NIEDB); Mr. Andreassen (Alaska Municipal League); Chief Laboucan-Avirom (Woodland First Nation); Mr. Helin (Lax Kw’alaams Band); and Dr. Hemming (Professor, Flinders University).

[23] RNNR Evidence: Professor Poelzer (University of Saskatchewan); Ms. Leach (NIEDB); Professor O’Faircheallaigh (Griffith University); Dr. Turi (Sámi University of Applied Sciences); and Dr. Dorough (as an individual).

[24] RNNR Evidence: Mr. Andreassen (Alaska Municipal League); Mr. Beamish (Anokasan Capital); Professor Hans-Kristian Hernes (Arctic University of Norway); Dr. Mack (Aleut International Association); and Ms. Whitford (Canative Energy).

[25] RNNR Evidence: Dr. Dalee Sambo Dorough (as an Individual); Dr. Mack: (Aleut International Association); Mr. Wallace Fox (IRC); Mr. Beamish (Anokasan Capital); Professor Poelzer; Ms. Leach (NIEDB); Mr. Andreassen (Alaska Municipal League); Chief Laboucan-Avirom (Woodland First Nation); Mr. Helin (Lax Kw’alaams Band); Dr. Hemming (Flinders University); and Mr. Sullivan (Gwich’in Council).

[27] RNNR Evidence: Mr. Fox (IRC); Professor Newman (University of Saskatchewan); Ian Jacobsen of Ontario Power Generation (OPG/CEA); and Mr. Duschenes (DIAND).

[28] RNNR Evidence: Mr. Fox (IRC); and Mr. Duschenes (DIAND).

[29] RNNR Evidence: Mr. Sullivan (Gwich’in Council); Mr. Fox (IRC); Professor Poelzer (University of Saskatchewan); Ms. Leach (NIEDB); Professor Newman (University of Saskatchewan); Mr. Perera (CEA); Chief Laboucan-Avirom (Woodland First Nation); Mr. Jacobsen (OPG); Ms. Whitford (Canative Energy); Chief Wapass (IRC); Mr. Fox (IRC); Mr. Perera (CEA); and Mr. Insley (Canative Energy).

[30] RNNR Evidence: Dr. Hemming (Flinders University); Ms. Leach (NIEDB); and Mr. Duschenes (DIAND).

[31] RNNR Evidence: Professor Poelzer (University of Saskatchewan); and Ms. Whitford (Canative Energy).

[32] RNNR Evidence: Chief Louis (AFN); Professor Poelzer (University of Saskatchewan); Dr. Dorough (as an individual); Generation Energy Council (NRCan); and Mr. Smith (Inuvialuit Regional Corporation).

[33] RNNR Evidence: Mr. Smith (Inuvialuit Regional Corporation); Professor Poelzer (University of Saskatchewan); Dr. Dorough (as an individual); Professor Newman (University of Saskatchewan); Mr. Sullivan (Gwich’in Council); and Mr. Duschenes (DIAND).

[34] RNNR Evidence: Professor Poelzer (University of Saskatchewan); Dr. Dorough (as an individual); Professor Newman (University of Saskatchewan); Mr. Sullivan (Gwich’in Council); and Mr. Duschenes (DIAND).

[35] Finnmark Kraft is owned by a mix of private, municipal and co-operative utilities, jointly developing local wind and hydroelectric power in northern Norway. AVEC is the largest Indigenous electricity co-operative in the world by territory, serving 57 communities in rural Alaska.

[36] RNNR Evidence: Mr. Smith (Inuvialuit Regional Corporation); Dr. Liza Mack (Aleut International Association); Chief Erasmus (Arctic Athabaskan Council); and Professor Gunn (University of Manitoba).

[37] RNNR Evidence: Mr. Duschenes (DIAND); Dr. Dorough (as an individual); Chief Louis (AFN); and Mr. Helin (Laz Kw’alaams Band); Mr. Sullivan (Gwich’in Council). Also see: Principles respecting the Government of Canada's relationship with Indigenous peoples (Government of Canada).

[38] RNNR Evidence: Professor Newman (University of Saskatchewan); and Dr. Dorough (as an individual).

[40] RNNR Evidence: Mr. Insley and Ms. Whitford (Canative Energy).

[41] RNNR Evidence: Chief Louis (AFN); Ms. Whitford (Canative Energy); Mr. Fox (IRC); Chief Laboucan-Avirom (Woodland First Nation); Ms. Leach (NIEDB); and Professor Poelzer (University of Saskatchewan).

[42] RNNR Evidence: Mr. Fox (IRC); Mr. Smith (Inuvialuit Regional Corporation); Ms. Whitford (Canative Energy); Mr. Beamish (Anokasan Capital); Professor Poelzer (University of Saskatchewan); and Mr. Insley (Canative Energy).

[43] RNNR Evidence: Mr. Duschenes (DIAND); Ms. Sloan (NRCan); Ms. Velshi (CNSC); Dr. Turi (Sámi University of Applied Sciences); and Professor Hans-Kristian Hernes (Arctic University of Norway).