HUMA Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

|

During the Committee’s study on advancing inclusion and quality of life for seniors, witness testimony addressed the diversity of the population often described as simply “seniors” and stressed the urgency, and opportunities, inherent in having an increasingly aged portion of the Canadian population. This chapter provides background information on demographic trends, and outlines the major challenges as well as opportunities related to economic and social inclusion. This overview will also touch on the federal government’s role in advancing inclusion and quality of life for seniors. Some witnesses highlighted the importance of recognizing that those over a certain age (usually 65), often referred to as “seniors” are not a homogenous group, pointing to diversity in physical ability, income, education, and living circumstances among these individuals. For example, Irene Sheppard of Fraser Health summarized the population’s diversity: I've learned that defining a senior is like trying to define a sunset: no two are truly alike. There are some general categories, of course, ranging from the vibrant, active senior to the physically and cognitively frail senior, but age is not the defining characteristic of a senior.[2] In this report, the terms “seniors” and “older Canadians” are both used, generally applying to those aged 65 and older. However, it is important to remember these terms do not describe any economic, social, or physical frailty. A. THE DEMOGRAPHIC SHIFT1. Population AgingSeveral witnesses cited the demographic shifts identified in the 2016 Census, when, for the first time, Canadians aged 65 and older outnumbered those aged 17 and younger. The 2016 population of 65 years and older was estimated to be 5.9 million. “[D]efining a senior is like trying to define a sunset: no two are truly alike.” Figure 1.1 illustrates the growth trends in both the working age, senior, and younger populations. This demographic shift has been described as a “grey tsunami.”[3] It is noted that children from birth to age 14 and Canadians aged 65 and older have historically been understood to be dependent on the working-age population, aged 15 to 64. Thus the demographic shift is from children being the larger dependent population to seniors being the larger group. Figure 1.1: Percentage of the Population: 0–17 Years, 18–64 Years and 65 Years and Over

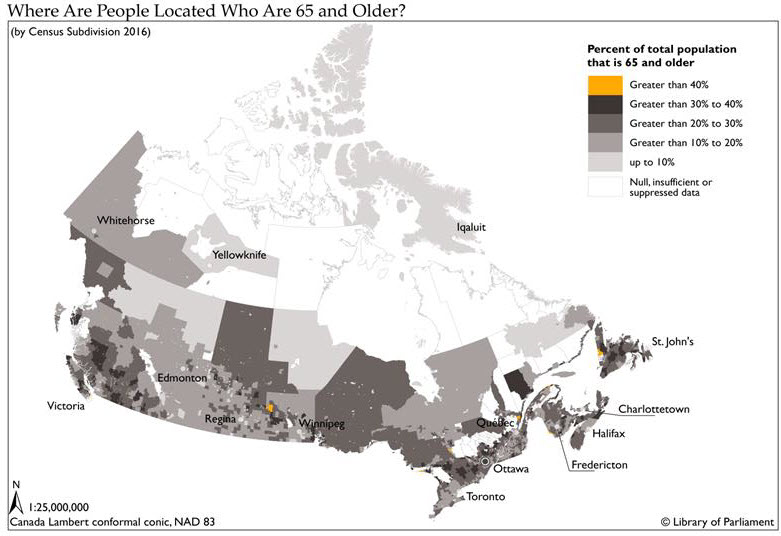

Source: Figure prepared by the author using data obtained from Statistics Canada, CANSIM Table 051-0001: Estimates of population, by age group and sex for July 1, Canada, provinces and territories, annual. While a significant portion of seniors have low incomes (see Figure 2.2 on page 25), several witnesses pointed out that the current generation of seniors is better educated, with greater labour force attachment, retirement savings, and pension benefits than previous generations. For example, as described by Birgit Pianosi, associate professor in the Gerontology Department at Huntington and Laurentian Universities: Today is different from the past. Older adults of today and the future will be much healthier, wealthier, and better educated than those of previous generations. Declining fertility has led to greater female labour force participation. Fewer children mean healthier, smarter, and better educated children. Demographic projections indicate further gains in longevity, including gains in healthy life expectancy, so we really need to look at older adults from a very different perspective.[4] 2. The number of seniors aged 85 and older is increasing rapidlyOver 770,780 people aged 85 and older were enumerated in the 2016 Census. This represents just over 2% of the population. Between 2011 and 2016, the number of people aged 85 and older grew by over 19.4%. This was nearly four times the rate for the overall Canadian population, which grew by 5% during this period. This population will likely continue to increase rapidly as life expectancy is increasing and the large baby boomer cohort (people born between 1946 and 1965) will reach age 85 starting in 2031.[5] Centenarians were actually the fastest growing population in Canada between 2011 and 2016, with a growth of 41.3% during this period. In 2016, the Census enumerated 8,230 centenarians.[6] 3. Women outnumber men but the gap is narrowingWhile there are more women over the age of 65 than men, this gap is narrowing. In 2016, women represented 54.5% of the population aged 65 and over, while men accounted for 45.5%. In 2006, women comprised 56.4% of the older population and men 43.6%.[7] This trend is related to higher gains in life expectancy among men, which means that the gap in life expectancy between men and women is narrowing.[8] 4. Geographic distribution of the population aged 65 and olderAnother significant dynamic of the senior population in Canada is that it is not distributed equally across the country. Atlantic Canada is on average older than the rest of the country. Alberta, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and the territories are younger. Also predictably, there are concentrated pockets of retired seniors where the climate, physical and social conditions are more favourable.[9] Figure 1.2 illustrates selected larger population centres with significant senior populations. Regions in Canada that have a larger proportion and larger numbers of seniors need to consider and deliver different services than regions with younger populations.[10] Figure 1.3 illustrates how seniors are distributed regionally across the country. Figure 1.2: Selected Larger Population Centres (with 5,000 plus population) with Significant Senior Populations

Note: Numbers of people age 65 and over are represented by the green bars – left axis. The percentage of the population age 65 and over is represented by the yellow diamonds – right axis. Source: Figure prepared by the authors using data obtained from Statistics Canada 2016 Census Data Tables, Age and Sex Highlight Tables, 2016 Census, Census subdivisions (municipalities) with 5,000-plus population. Figure 1.3: Geographic Distribution

B. CHALLENGES ASSOCIATED WITH AGINGThe Committee heard that more Canadians are enjoying a healthy life well past the age of 65, participating actively in their workplaces, their families and their communities. However, getting older can take its toll on the well-being of older Canadians. While economic, physical and social difficulties can occur at any age, the general trend is toward greater challenges at more advanced ages. For example, a greater proportion of seniors experience low-income[11]after the age of 75, than between the ages of 65 and 74.[12] Several witnesses described the debilitating results of inadequate income, including poorer health status,[13] social isolation,[14] and reduced capacity to provide care to others in need.[15] At the same time, witnesses told the Committee that people are more likely to develop chronic health conditions[16] and to need more assistance with activities of daily living[17] as they age. These challenges, in turn, make affordable and accessible housing more important, and may trigger the need to move to a collective living situation that provides more support. As witnesses told the Committee, many seniors do not wish to move from their homes[18] and most have no plans to move at all.[19] Witnesses also identified appropriate home care as vital to allowing people to “age in place.”[20] Witnesses noted that “place” could refer to individual homes and/or to the communities in which they live (discussed in greater detail in the section of the report focussed on social inclusion). However, some witnesses expressed that aging in their homes may not be for everyone, particularly in the later years of life. An official from the Public Health Agency of Canada told the Committee that “the prevalence of dementia increases with age group, from 0.8% in the 65- to 69-year age group to 24.6% in the 85-plus age group.”[21] Census 2016 data show that the need to move to a collective dwelling increases significantly with age.[22] 1. Challenges facing all orders of governmentThe challenges facing all orders of government were articulated by Isobel Mackenzie, Seniors Advocate of British Columbia. Ms. Mackenzie highlighted the experiences of two fictional 85‑year-old single seniors, Margaret living in Brandon, Manitoba and Helen living in Vancouver, British Columbia. They are both of sound mind. However, they have some frailty and require daily help in the morning to get up, wash, dress, and check on their medications. They both have an annual income of $27,000 but because of significant differences in shelter costs and access to health care and home supports across provinces, they are left with very different disposable incomes.[23] Table 1.1 illustrates the different expenses that Helen and Margaret must pay for rent and homecare supports. Even though these women are the same age and have the same income, same health care needs, same size of apartment, and same citizenship, at the end of the month Margaret has $1,265 to spend on groceries, transportation, clothing, haircuts, cable, Internet access, social engagements, and cultural activities. Helen has $296. These vastly different circumstances can have profound implications for income security, quality of life and the capacity of seniors to participate in their communities.[24] Table 1.1: Rent and Home care supports for Helen and Margaret

Note: Rent is for a one bedroom apartment. Helen pays $1,159 market rent minus $46 shelter grant. Home support costs Helen $19 a day co-payment. It does not include housekeeping. Margaret’s home support care is covered by her provincial health plan which includes housekeeping support. Margaret has an employer paid retirement benefit which includes extended health and dental coverage. While Margaret and Helen’s stories illustrate vastly different realities between urban communities, the Committee also heard important testimony related to the different realities that seniors in rural, suburban, and remote northern communities experience. Much like in urban communities, inclusion and quality of life can be very different depending on shelter costs and access to transportation, health care and important homecare supports.[25] C. OPPORTUNITIES ASSOCIATED WITH AGINGA report by the Special Senate Committee on Aging, tabled in the Senate in April 2009 was entitled Canada’s Aging Population: Seizing the Opportunity.[26] Testimony and briefs submitted over the course of this study echoed the theme expressed by the Senate report that Canada’s aging population can be understood as an opportunity. As Canadians are living longer and healthier lives and are becoming more educated, they are remaining active in the labour force longer.[27] An official from Employment and Social Development Canada told the Committee that the labour force participation of people aged 65 to 69 years old had increased from 15.6% in 1976 to 26.2% in 2016.[28] Significant increases in work activity were observed at all ages, for men and women alike. In 2015, more than 53% of senior men reported working at age 65, including about 23% who worked full year, full time. In 2015, fewer women (nearly 40%) reported working at age 65, yet this was nearly double the number of 65-year-old women who reported working 20 years earlier.[29] Witnesses described an opportunity to encourage increased labour force participation in this older, healthier population,[30] and described its economic benefits in terms of increasing productivity, incomes, and tax revenues.[31] A number of witnesses also described the opportunity to develop and apply new technologies to enhance the well-being of Canada’s seniors. One witness pointed out how technologies are already minimizing the impacts of some health challenges associated with aging, including reducing the impacts of hearing and vision loss,[32] while others pointed to the promise of technology to simplify some of the daily activities of living,[33] and increase access to home health care.[34] Others foresaw the widespread application of self-driving vehicles as a solution for older Canadians who are no longer able to drive.[35] Still other witnesses noted that not all seniors have access to high-speed Internet services, creating some challenges in accessing the services and supports they need.[36] D. THE FEDERAL ROLEDuring this study, many witnesses identified ways that the challenges associated with aging could be addressed and opportunities enhanced with policies and programs that provide adequate and secure incomes and promote the continued inclusion of Canadians as they age. Under the broad headings of economic and social inclusion, many aspects of these initiatives fall within provincial and territorial jurisdictions, as they deal with policy areas such as social assistance, social services and supports, health services and supports, and housing. However, the federal government also has direct responsibility over these areas for particular populations, including Indigenous people, veterans and newcomers. In addition, federal involvement is extended through transfers to other orders of government, income supports to individuals, benefits through the income tax system, and collaborative work with provincial and territorial counterparts. 1. Economic inclusionFederal income support programs are an essential part of the retirement income system. These federal programs are the Canada Pension Plan, Old Age Security and the Guaranteed Income Supplement. Despite persistent poverty among some seniors, addressed in greater detail in the next chapter on economic inclusion, these initiatives have resulted in significant reductions in seniors’ poverty.[37] Witnesses had many proposals to improve these federal programs, which will also be included in the next chapter. Federal taxation policy also has an impact on the economic security and inclusion of Canadian seniors. In particular, tax reduction to encourage private retirement savings and credits associated with age and with pension income have a direct impact on the available economic resources available to seniors. Yet, as described above, federal income supports cannot offset differences in provincial and territorial programs which can translate into vastly different levels of post-necessity income even among seniors who are in highly similar situations.[38] 2. Social inclusionAs noted above, even the narrowest definition of the federal role in areas such as housing, health and social services recognizes federal responsibility for Indigenous persons and immigrants to Canada. Testimony before the Committee described the particular marginalization of Indigenous[39] and immigrant[40] seniors in Canada. Within an intergovernmental context, the federal government provides significant funding through both the Canada Social Transfer and the Canada Health Transfer to provincial and territorial governments. The Canada Health Act provides criteria for cost-shared funding, originally intended to cover only costs associated with doctors and hospitals. The most recent bilateral accords included a component specifically funding home care. Similarly, the National Housing Strategy has been developed in collaboration with provincial and territorial governments with expected financial contributions by all orders of government. Additional collaboration in other policy areas is facilitated by regular meetings of federal, provincial and territorial ministers with responsibility in these areas.[41] Other federal funding that has a direct impact on the social inclusion of seniors is for health research through the Canadian Institutes of Health Research,[42] and for scientific and social research, through the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council[43] and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council respectively.[44] 3. Federal leadershipProvincial and territorial governments are responsible for the adoption and enforcement of building and fire codes. However, the National Building Code of Canada[45] and other federal regulatory frameworks are the basis for most provincial and territorial codes, often with slight variations or additions.[46] Specific recommendations with respect to the National Building Code[47] were proposed as a mechanism for increasing accessibility of housing for seniors and others with mobility impairments across Canada. Witnesses identified the need for federal leadership in matters of both economic and social inclusion, most frequently to result in greater pan-Canadian consistency in services and supports offered to seniors. These are addressed in greater detail in the subsequent chapters. Finally, there was widespread agreement among witnesses that a “national seniors strategy” would be welcome. Different stakeholders, in both written submissions and testimony, had specific ideas of what should be included in such a strategy and what specific issues and perspectives should frame such an initiative. These are described in greater detail in a later chapter focussed on a national seniors strategy. [2] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 17 October 2017, 1540 (Irene Sheppard, Executive Director, Fraser Health). [3] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 19 October 2017, 1535 (Alison Phinney, Professor, School of Nursing, University of British Columbia, as an individual) and Evidence, 2 November 2017, 1635 (Ian Lee, Associate Professor, Sprott School of Business, Carleton University, as an individual). [4] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 31 October 2017, 1355 (Birgit Pianosi, Associate Professor, Gerontology Department, Huntington and Laurentian Universities, as an individual). [5] Statistics Canada, “A portrait of the population aged 85 and older in 2016 in Canada,” Census in Brief, 3 May 2016. [6] Ibid. [7] Ibid. [8] Statistics Canada. Age and Sex Highlight Tables, 2016 Census, 3 May 2017. [9] Ibid. and Statistics Canada, “A portrait of the population aged 85 and older in 2016 in Canada,” Census in Brief, 3 May 2016. [10] Ibid. [11] The census release uses the After Tax Low Income Measure (LIM-AT). The concept underlying the LIM-AT is that a household has low income if its income is less than half of the median income of all households. Thus, it is a relative measure of low income. [12] Statistics Canada, Household income in Canada: Key results from the 2016 Census, 9 September 2017. [13] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 26 October 2017, 1620 (Laurent Marcoux, President, Canadian Medical Association) and Evidence, 3 October 2017, 1600 (Lola-Dawn Fennell, Executive Director, Prince George Council of Seniors). [14] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 9 November 2017 (Olufemi Adegun, President, Peel, Ontario Branch, Senior Empowerment Assistance Centre) and Evidence, 17 October 2017, 1530 (Nicole Laveau, representative, Comité retraite et fiscalité, Association québécoise de défense des droits des personnes retraitées et préretraitées). [15] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 2 November 2017, 1545 (Marika Albert, Executive Director, Community Social Planning Council of Greater Victoria). [16] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 5 October 2017, 1540 (Bonnie-Jeanne MacDonald, Actuary and Senior Research Fellow, Ted Rogers School of Management, Ryerson University, as an individual). [17] Ibid., 1600 (Isobel Mackenzie, Seniors Advocate, Office of the Seniors Advocate of British Columbia). [18] See, for example, HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 2 November 2017, 1655 (Glenn Miller) and Evidence, 19 October 2017, 1640 (Raza M. Mirza, Network Manager, National Initiative for the Care of the Elderly). [19] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 9 November 2017, 1540 (Donald Shiner, Professor, Atlantic Seniors Housing Research Alliance, Mount Saint Vincent University, as an individual). [20] See, for example, HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 19 October 2017, 1610 (Margaret M. Cottle, Palliative Care Physician, as an individual) and Evidence, 26 October 2017, 1600 (Laurent Marcoux). [21] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 8 June 2017, 1205 (Anna Romano, Director General, Centre for Health Promotion, Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention Branch, Public Health Agency of Canada). [22] Statistics Canada, “A portrait of the population aged 85 and older in 2016 in Canada,” Census in Brief, 3 May 2016. [23] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 5 October 2017, 1400 (Isobel Mackenzie), Written submission from the Office of the Seniors Advocate of British Columbia, October 2017. [24] Ibid. [25] See, for example, HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 7 November 2017, 1550 (Michèle Osborne, Executive Director, Centre action générations des aînés de la Vallée-de-la-Lièvre) and Evidence, 26 November 2017, 1720 (Meredith Wright, Director of Speech-Language Pathology and Communication Health Assistants, Speech-Language & Audiology Canada) and Written submission from Manitoba Seniors’ Coalition, October 2017, p. 8. [26] Special Senate Committee on Aging, Final Report: Canada’s Aging Population: Seizing the Opportunity, April 2009. [27] For additional data on the workers 65 years and older please see Appendix C. [28] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 8 June 2017, 1150 (Nancy Milroy Swainson, Director General, Seniors and Pensions Policy Secretariat, Income Security and Social Development Branch, Department of Employment and Social Development). [29] Statistics Canada. Working seniors in Canada, 29 November 2017. [30] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 5 October 2017, 1530 (Charles M. Beach, Professor Emeritus, Economics Department, Queen's University, as an individual) and 1655 (Isobel Mackenzie). [31] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 17 October 2017, 1545 (Michael R. Veall, Professor, Department of Economics, McMaster University, as an individual). [34] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 7 November 2017, 1540 (Leighton McDonald, President, Closing the Gap Healthcare, Canadian Home Care Association) and Written submission from Canadian Institutes of Health Research, October 2017. [35] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 31 October 2017, 1550 (Kevin Smith, Representative, Seniors First BC) and Evidence, 2 November 2017, 1700 (Ian Lee). [36] See, for example, HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 3 October 2017, 1625 (Wanda Morris, Vice-President, Advocacy, Canadian Association of Retired Persons) and 1600 (Lola-Dawn Fennell). [37] See, for example, HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 5 October 2017, 1530 (Charles M. Beach) and Evidence, 3 October 2017, 1530 (Tammy Schirle, professor, Department of Economics, Wilfrid Laurier University, as an individual). [39] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 8 June 2017, 1115 (Lyse Langevin, Director General, Community Infrastructure Branch, Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development). [41] For specific examples of policy collaboration between Federal, Provincial, Territorial and Municipal governments see: The Canadian Intergovernmental Conference Secretariat. [42] Examples of funded research by the institutes include “Using Internet Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy with Older Adults: Is Age a Factor?” and “Creating a Sustainable System of Care for Older People with Complex Needs: Learning from International Experience.” [43] Examples of recently funded research by this council include “Advancing engineered structures for Canada’s aging population,” and “Adaptable Smart Environments for Elderly People.” [44] Examples of recently funded research by this council include “A cross-cultural investigation of the effects of aging beliefs on cognitive performance in older adults,” and “Population aging, implications for asset values, and impact for pension plans: an international study.” [45] National Research Council, Model code adoption across Canada. [46] Ibid. [47] See, for example, HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 9 November 2017, 1540 (Donald Shiner) and Evidence, 2 November 2017, 1615 (Glenn Miller) and Written submission from CARP, October 2017, p. 2. |