HUMA Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

CHAPTER 3: EDUCATION, SKILLS TRAINING AND EMPLOYMENTA. Background: Federal Contributions to Education, Skills Training and Employment1. Main federal programsWhile education, skills training and employment are typically matters mostly under provincial jurisdiction, the federal government is involved in these areas in a number of important ways. For example, the federal government provides financial support to the provinces and territories through major financial transfers in order to assist them in the provision of a variety of programs and services. One such transfer is the Canada Social Transfer, which is a block transfer to the provinces and territories in support of early childhood development and child care, post-secondary education, as well as social assistance and social services.[106]The federal government also administers the Aboriginal Head Start On Reserve program and the Aboriginal Head Start in Urban and Northern Communities program, which fund Indigenous community-based organizations that deliver early childhood learning and development programs to First Nations, Inuit, and Métis children.[107] In addition, the federal government offers student financial assistance in the form of grants and loans, as well as repayment assistance plans, through initiatives such as the Canada Student Loans program and the Canada Student Grants, with the objective of encouraging Canadians to pursue post-secondary education. Specifically, the Canada Student Grants are available for students from low- and middle-income families, students with dependants, part-time students, as well as students with permanent disabilities.[108] Further, the Registered Education Savings Plan (RESP), which is a savings account for children meant to offset the future costs of post-secondary education, is linked to the following federal savings incentives:

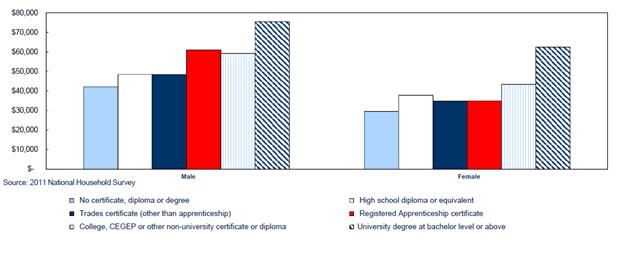

In her appearance before the Committee, one of the representatives from Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC) indicated that approximately 3.5 million children in Canada have more than $47 billion accumulated in RESPs for their future post-secondary education.[110] Other financial incentives offered by the federal government to support post-secondary education include tax credits for tuition fees and for the interest paid on student loans.[111] The federal government also provides financial support for the post-secondary education of First Nation and eligible Inuit students through programs like the Post-Secondary Student Support Program and the University and College Entrance Preparation Program. Designed to meet the specific needs of Indigenous peoples and communities, these programs offset the costs associated with tuition, school supplies, travel and living expenses. The Post-Secondary Student Support Program is delivered by Indigenous communities and supports approximately 23,000 students annually.[112] In addition to providing financial assistance for post-secondary education, the federal government allocates resources towards increasing literacy and essential skills in Canada. Through the Literacy and Essential Skills program, funding is provided to improve the literacy and essential skills of Canadians as well as to help them to better prepare for, obtain, and maintain employment.[113] Further, through the Financial Consumer Agency of Canada (FCAC), the federal government promotes financial literacy. Specifically, the national strategy for financial literacy (“Count me in, Canada”), which is led by the FCAC, has the objective of helping people “manage their money and debt wisely, plan and save for their financial future, as well as prevent and protect themselves from fraud and financial abuse.”[114] The federal government also invests in skills training and employment through the Labour Market Development Agreements and the Canada Job Fund Agreements, which are funding agreements with the provinces and territories to help unemployed or underemployed Canadians access the training and services they need to pursue opportunities for a better future. It should be noted that the Canada Job Fund Agreements include the Canada Job Grant, which is designed to help employers train new or existing employees for jobs that need to be filled.[115] Each year, the federal government provides the provinces and territories $1.95 billion through the Labour Market Development Agreements and $500 million through the Canada Job Fund Agreements.[116] Finally, financial support is also provided by the federal government to those facing multiple barriers to training and employment such as youth, people with disabilities and Indigenous peoples. Through the Youth Employment Strategy, for example, funding is provided for employers and organizations to create job opportunities for youth, as well as to design and deliver activities to enable youth to develop a broad range of skills and make informed career decisions. Under this initiative, the Skills Link stream helps vulnerable youth, especially those individuals who have dropped out of high school or are not pursuing education. Similarly, the Opportunities Fund for Persons with Disabilities provides funding for organizations to help people with disabilities prepare for, obtain and maintain employment or self-employment. Through the Aboriginal Skills and Employment Training Strategy, Indigenous people are enabled to develop employment skills and pursue training for lasting employment.[117] 2. Budget 2016 measuresBudget 2016 announced a series of contributions in the areas of education, skills training, and employment, listed in detail in Appendix A of this report. Notably, Budget 2016 announced an investment of $500 million in 2017-2018 to support the establishment of a national framework on early learning and child care, in collaboration with the provinces and territories. Of this amount, $100 million was proposed in relation to Indigenous child care and early learning on reserve.[118] It should be noted that, in her appearance before the Committee, the representative from INAC indicated that the Department is currently working with other federal partners in order to support school readiness by, among other measures, developing an early learning and child care framework for First Nations.[119] Budget 2016 also announced a series of investments which have the objective of making post-secondary education more affordable. These measures include enhancing the Canada Student Grants by, for example, increasing the grants for students from low-income families from $2,000 to $3,000 per year. In addition, Budget 2016 proposed to increase the loan repayment threshold under the Canada Student Loans Program’s Repayment Assistance Plan, so that repayment is only required once a borrower is making at least $25,000 a year, instead of $20,210 a year.[120] Further, Budget 2016 announced investments to enhance the skills and employment opportunities of unemployed and underemployed Canadians, through an additional investment of $125 million for the Labour Market Development Agreements and an additional $50 million towards the Canada Job Fund Agreements in 2016-2017. Additional investments were also announced with respect to the Youth Employment Strategy in the form of $165.4 million in 2016-2017. Budget 2016 also proposed the allocation of $15 million over two years, starting in 2016-2017, towards the Aboriginal Skills and Employment Training Strategy.[121] B. What the Committee Heard1. Education and skills trainingWitnesses appearing before the Committee agreed that a strong link exists between education and skills training and poverty reduction. According to ESDC officials “[h]igher levels of education are linked to higher earning potential, a lower likelihood of unemployment, greater resilience during economic downturns, and many other public, private, social, and economic benefits.”[122] The following graphs provided by Statistics Canada show that, for both men and women, those with less than a high school education have the lowest earnings while those with a university degree have the highest earnings. The graphs also reveal that education significantly reduces the gap in employment rates between the off-reserve Indigenous population and the rest of the population, as well as between people with disabilities and those with no disabilities.[123] Chart 3: Median employment income of full time full year paid employees aged 25 to 64 by highest certificate, diploma or degree, 2010

Source: 2011 National Household Survey Chart 4: Unemployment rates of total population and off reserve Aboriginal population aged 15 and over, Canada, 2015

Source: Education indicators in Canada: Report of the Pan-Canadian Education Indicators Program, June 2016 Chart 5: Employment rate adjusted for age difference, by education level and severity of disability

Source: Canadian Survey on Disability, 2012 While the importance of education and skills training for reducing poverty was well established, witnesses cautioned that there are multiple challenges along the way to improving educational attainment. These challenges, the testimony noted, arise at various stages of the educational system, from early learning to adult education, and may have a greater impact on individuals from vulnerable groups. a. Early learning and childhood developmentThe first few years in a child’s life were described by witnesses as essential for building the skill set necessary for breaking the cycle of multigenerational poverty, especially literacy, numeracy, and language skills. Jennifer Flanagan, Chief Executive Officer at Actua, explained that skills development must also start early in elementary school for the fields of science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM), fields in which children and youth from low-income families have traditionally been under-represented.[124] Heather Smith, President of the Canadian Teachers’ Federation, cautioned that, given that schools are preparing children for a workplace or a job that may not yet exist, more emphasis should be placed on soft skills like critical thinking and problem solving. Similarly, Kory Wood, President of Kikinaw Energy Services, spoke about the importance of developing goal setting skills from an early age, especially for individuals trying to overcome multigenerational poverty.[125] Witnesses also noted that children and youth who live in poverty face unique challenges, such as housing inadequacy and food insecurity, and therefore require additional resources in order to succeed in the education system. These additional resources, as explained in a brief submitted by Living SJ, are unique for each child and can include enriched education, mentorship as well as social, health, and recreation supports. Witnesses therefore emphasized the importance of after-school and other programs, noting that schools alone cannot supply what every child needs.[126] During its study, the Committee learned that child poverty is a reality in Canada, with the City of Saint John, New Brunswick, having the highest rate of child poverty in the country. The Committee also heard that numerous organizations across Canada are working towards improving childhood development outcomes. For example, the Boys and Girls Clubs of Canada provide after-school programming for children and youth in impoverished communities, including financial literacy education. Similarly, the YMCA of Greater Saint John operates an early learning centre, which offers free kindergarten readiness programs for children not in licensed care, among other supports for families.[127] Overall, witnesses noted that greater resources are needed for early learning and childhood development, and welcomed federal initiatives towards the establishment of a national strategy for early learning. While witnesses indicated that there is a role for the federal government to play in this regard, Reagan Weeks, Assistant Superintendent at the Prairie Rose School Division, suggested that it would be critical to modify any national strategy to fit the community context. In her opinion, if children are not integrated with the larger learning community, the risk exists for the current gap in early learning to be widened inadvertently. In addition, Jeffrey Bizans, Co-Chair of EndPovertyEdmonton, indicated that it would be important to build the well-educated workforce that is needed for high-quality care, as well as ensure that research is conducted to support continued improvements in early learning and care.[128] b. Saving for post-secondary education and the Registered Education Savings PlanWhile the objective of RESPs and associated savings incentives is to accumulate funds towards the future costs of post-secondary education, Courtney Hare, Manager of Public Policy at Momentum, indicated that not all parents are opening RESP accounts for their children and that, as a result, unclaimed Canada Learning Bond funds amount to approximately $3 billion. In her testimony, she noted the need for more asset building programs in order to address this problem, suggesting lack of knowledge about tools like the RESPs and limited financial means as contributory factors. Derek Cook, Director of the Canadian Poverty Institute, also noted that limits on allowable assets for welfare applicants lead indirectly to people divesting their RESPs in order to qualify.[129] A brief submitted by the Canadian Alliance of Student Associations further explained that RESPs are being “disproportionately enjoyed” by higher income families as greater RESP contributions trigger a higher percentage in savings grants from the federal government.[130] Data shared by Statistics Canada with the Committee shows that, while parents in the lowest income category are increasingly saving for their children, as of 2013, families with household income between $30,000 and $50,000 accumulated an average of $6,500 in RESPs, while families with household income of $100,000 and over accumulated $12,713.[131] Accordingly, the Canadian Alliance of Student Associations recommended in its brief that access to this program be improved for low-income applicants. For example, rather than requiring an application, the brief suggested that the Canada Learning Bond be granted automatically to those who qualify when filing their taxes and that it be proactively distributed through a voucher that could be deposited into a child’s RESP plan, at an approximate cost of $200 million. In addition, the brief recommended that the Canada Education Savings Grants be reduced from 20% to 10% for families with a total annual income in the top quintile of Canadian incomes in order to pay for the expansion of the Canada Learning Bond, an initiative that is estimated to save approximately $200 million.[132] Similarly, Ms. Hare suggested that funding be shifted away from the Canada Education Savings Grant to the Canada Learning Bond.[133] c. The cost of post-secondary and postgraduate educationThe Committee also learned about the rising cost of post-secondary and postgraduate education. According to data provided by Statistics Canada during the study, undergraduate tuition fees have increased in almost every province during the period from 2008-2009 to 2016-2017, except in the provinces of Alberta and Newfoundland and Labrador.[134] Bilan Arte, National Chairperson of the Canadian Federation of Students, explained that, while post-secondary education is required for most jobs in today’s labour market, it is disproportionately accessed by Canadians from higher income families, with individuals from vulnerable groups such as new immigrants, refugees, visible minorities, people with disabilities, and youth from low-income families often being left behind for lacking the necessary resources.[135] According to the brief submitted by the Canadian Alliance of Student Associations, for Indigenous people, lack of funding is one of the principal barriers to accessing post-secondary education, despite the existence of the federal Post-Secondary Student Support Program. Testimony provided by witnesses in this regard revealed that annual funding increases for this program have been capped at 2% for approximately 20 years and that, as a result, funding for the post-secondary education of First Nation and eligible Inuit students has not kept up with the rise in tuition fees and living costs or with the growing demand to pursue post-secondary education. Danielle Levine, Executive Director at the Aboriginal Social Enterprise Program, explained to the Committee that this “significant gap in funding” has led band councils to make difficult decisions, such as funding the post-secondary education of selected individuals or supporting enrolment in trades and bachelor’s degrees at the expense of other programs. Ms. Arte added that band councils are also more likely to fund programs that take fewer years to complete, and that many Indigenous students are forced to drop out of post-secondary education because they lack ongoing financial assistance. The waiting list of Indigenous youth who would like to pursue higher levels of education, she noted, has been estimated at 10,000 students.[136] Witnesses also spoke about financial barriers to accessing postgraduate education, indicating that masters and other graduate degrees are associated with lower unemployment rates and higher incomes. According to the Canadian Alliance of Student Associations’ brief, given that these programs often charge much higher tuition fees than other post-secondary education programs, low-income Canadians as well as students from under-represented groups are less likely to access them. This is especially the case as federal support for graduate students is primarily provided through merit-based scholarships rather than through needs-based grants.[137] Even in circumstances where elevated tuition fees do not constitute a barrier to accessing higher levels of education, witnesses agreed that they still constitute a significant burden on people. For example, elevated tuition fees may force students to balance school and work in order to make ends meet, may contribute to high student debt upon graduation, and may have other long-term societal repercussions such as individuals postponing leaving their family homes or delaying marriage or having children. According to data submitted by Statistics Canada, more than 4 out of 10 post-secondary education students who graduated in 2010 had debt upon graduation.[138] Speaking about the Canada Student Loans Program’s Repayment Assistance Plan, Ms. Arte cautioned that, although the threshold has been increased so that repayment is only required once a borrower is making at least $25,000 a year, this figure still constitutes an earning level that is very close to the poverty line. Overall, in order to address the above-noted challenges, witnesses called for additional allocation of resources with respect to post-secondary and postgraduate education. Ms. Arte, for example, supported the notion of a fully funded, universal system of post-secondary education. In its brief to the Committee, the Canadian Poverty Institute specifically recommended that the Canada Social Transfer be split in order to create a Canada Education Transfer (CET), that investment through the CET be increased to levels similar to those previously provided under the Canada Assistance Plan, and that conditions be established for the CET that would provide reasonable limits on tuition. Regarding the Post-Secondary Student Support Program, Ms. Arte recommended that the 2% cap on annual funding increases be removed, whereas the Canadian Alliance of Student Associations called for a fully funded program and for the long waiting list to be addressed. In its brief, the Canadian Alliance of Student Associations also suggested that the Canada Student Grants be expanded to include grant options targeted to under-represented groups and students with high financial needs, that the Canada Student Grants be indexed to the education component of the Consumer Price Index to maintain their purchasing power over the period of time a student is eligible to receive the grant, and that a Canada Student Grant for graduate students with high financial needs be established.[139] d. Financial literacy and vulnerable groupsThe Committee also obtained extensive testimony about the role that financial literacy can play in poverty reduction, especially for people from vulnerable groups. The FCAC informed the Committee that 34% of newcomers, 37% of low-income Canadians, and 50% of Indigenous people living off reserve struggle to pay or are not keeping up with bills and payments. Speaking about the importance of financial literacy, Jérémie Ryan, Director of Financial Literacy and Stakeholder Engagement at the FCAC, indicated as follows: We know that giving consumers the knowledge, skills and confidence to manage their money gives them more control. Our research tells us that confidence in particular plays a key role. If people are more confident, they are more likely to shop around, ask questions, negotiate, and use products and services that can help them manage their money and save, such as RESPs and TFSAs.[140] While the Committee was told about federal initiatives to improve financial literacy outcomes in Canada, such as “Count me in, Canada,” and about important work that is being done through financial empowerment programs offered by organizations like Momentum, witnesses expressed concerns about low-income Canadians’ increasing reliance on payday loans and similar services. Data provided by the FCAC reveals that the proportion of Canadians using payday loans has more than doubled, from 1.9% in 2009 to 4.3% in 2014.[141] According to Laura Cattari, Campaign Co-ordinator at the Hamilton Roundtable for Poverty Reduction, payday loans are provided for a very limited period of time, usually two weeks, and have an annual interest rate that is approximately 550%. As a result, she noted, many customers fall thousands of dollars in debt to payday lenders.[142] Witnesses also expressed concerns about the fact that financial planners are not properly regulated in Canada, often giving advice to low-income Canadians that is more damaging than beneficial. According to Wanda Morris, Chief Operating Officer at the Canadian Association of Retired Persons, very low-income earners are often encouraged to contribute to an RRSP as their investment vehicle when, in fact, this measure results in very little tax benefits at the time the contribution is made as well as in direct claw backs on their GIS or other benefits upon withdrawal.[143] The Committee was also told about financial literacy programming as it impacts Indigenous peoples. According to Ms. Levine, available financial literacy programming across Canada takes the form of group-based training and is not geared to the individual. Given that Indigenous peoples are often not receptive to speaking about their personal financial circumstances in a public forum, she noted that these programs are not always suitable for them.[144] Overall, witnesses recommended that financial literacy programming be personalized to an individual’s challenges and unique circumstances, and also called on the federal government to better regulate the payday loan industry as well as financial planners. Witnesses also suggested that the federal government work with the Canadian Bankers Association to update its 2014 low-cost account guidelines, with the objective of ensuring that more Canadians can access safe and affordable financial services. It was also suggested that the federal government invest in asset-building programs for low-income Canadians.[145] In addition, with respect to Indigenous peoples, Ms. Levine recommended that it would be important for the federal government to continue funding existing programming; as well as to invest in strategic areas, including asset development, through initiatives such as matched savings, affordable home ownership, and micro-finance.[146] e. Recognition of foreign credentialsAccording to Vanessa Desa, Vice-Chair of the Board of Directors for Immigrant Access Fund Canada, recent immigrants to Canada face additional challenges linked to education, including inequitable licensing processes as well as lack of access to financial resources for training and certification, all of which are having an impact on their poverty rates. Specifically, she noted that 41% of chronically poor immigrants have university degrees. In her appearance before the Committee, she described this situation as follows: Despite the fact that Canada actively recruits skilled immigrants for the contributions that they and their families can make to our economy and our future, we have not created the conditions to allow them to thrive. Despite their higher levels of education, on average, they face higher unemployment rates and lower wages than Canadian-born workers, and are disproportionately represented in Canadian poverty statistics... This is preventable poverty, devastating to the families who experience it and who arrive on our shores expecting so much more, and a huge loss to Canada’s economy and to all of us as Canadians.[147] A brief submitted by her organization explained that foreign credential recognition processes “lack clarity, are complex, vary by province and territory, and can be very lengthy.” For example, in order to have their credentials assessed, registered and licensed nurses have to apply to a national body before they can apply provincially. This national body will often contract with an organization in the United States, which will then collect the required documentation from employers, universities and registration bodies in the applicants’ home countries, and charge an additional fee if this documentation is neither in English nor French. The brief further explained that these processes are also very expensive, indicating that assessments of credentials along with fees for exams, tuition, books, and course materials can cost upwards of $50,000. These costs occur at the same time as earnings drop or cease during the licensing and training period as people devote their time and attention to studying. Unpaid internships, such as those for pharmacists and physiotherapists, for example, appear to be on the rise. In addition, those on social assistance face the risk of losing their funding if they obtain a loan from organizations such as Immigrant Access Fund Canada. As a result, Ms. Desa reported that, after four years in Canada, only 28% of newcomers with foreign credentials were able to have them recognized. In order to address the various challenges associated with the recognition of international qualifications among immigrants to Canada, Ms. Desa recommended that the systemic barriers in licensing and credential recognition processes continue to be addressed, despite progress made through the pan-Canadian framework developed under the Forum of Labour Market Ministers. Ms. Desa further suggested that the federal government ensure that the policies and practices of regulatory bodies and other stakeholders be aligned to better support the labour market integration process faced by immigrants. Finally, she recommended that the federal government “create an environment that inspires, supports, and rewards social innovation and social finance.”[148] 2. EmploymentIn addition to barriers linked to education and skills training, the Committee was told about challenges with respect to employment. These include gaps in the transition from education to employment, what some witnesses noted was an increase in various forms of precarious employment, as well as lack of affordable and accessible child care. People with disabilities, the testimony noted, also face additional challenges in obtaining and maintaining employment. The Committee learned that, combined, all of these factors are contributing to the poverty rates of people in vulnerable groups. a. The gap between education and employmentThe Committee heard that there are a series of challenges associated with the transition from education to employment which, when coupled with other issues such as precarious employment, are leading youth to question the value of post-secondary education. In this regard, Lynne Bezanson, Executive Board Member of the Canadian Council of Career Development, indicated as follows: There is ample evidence to demonstrate that career education and support services over the lifespan as well as workplace learning opportunities produce positive education and labour market outcomes, not in isolation but as key components, and in Canada they are traditionally underused as accessible and affordable labour market and poverty reduction strategies.[149] During her appearance before the Committee, Ms. Bezanson explained that the career services available to those transitioning from school to work, or simply from one job to another, are neither consistent nor coordinated. This is owed to a lack of collaboration at the community level, between the educational institutions and the business community, as well as at the national level. She noted specifically that successful programs, such as the one in place in New Brunswick that connects students in grades 10 to 12 with employers, are not widely known outside of that jurisdiction.[150] Further, witnesses indicated that although the overwhelming majority of jobs require prior work experience, this is actually very difficult to secure, especially as access to co-op programs and paid internships is very limited. The rate of on-the-job training for youth is also very low. According to Emily Norgang, Senior Researcher at the Canadian Labour Congress, for example, only 1 in 5 employers actually hire and train apprentices. While there are excellent programs to address some of these challenges, Ms. Bezanson noted that there are problems around access, implementation and sustained funding. There are also very few incentives to encourage employers to hire young graduates, or avenues for the business community to indicate what they need in order to hire more youth.[151] Data provided by Monique Moreau, Director of National Affairs at the Canadian Federation of Independent Business, reveals that, in 2015, a new hire with no previous work experience cost small businesses approximately $4,200 to train, while a new hire with some work experience cost approximately $2,800. Although small businesses invest heavily in training, she noted that “the current government model [of workforce development] does not fully address the training needs of small businesses, nor does it recognize the realities of training in a small business.”[152] For example, training investments made by the government do not always match the skills training that employers need, with on-the-job mentoring being the preferred method for employers. As a result, she indicated, 84% of small businesses reported in 2015 not having used government-sponsored programs over the previous three years. Those few businesses that did use them, however, identified apprenticeship-tax credits as their preference. Ms. Hare further explained that the Canada Job Grant has not always been used to benefit those individuals who experience barriers to employment. In Alberta, for example, she indicated that 98% of these funds have been used to support people who were already working.[153] Avenues suggested by witnesses to close the gap in the transition from education to employment included the establishment of a national school-to-work transition strategy, that would be built on the foundation of successful initiatives in place in Canada and abroad and that would bring together key stakeholders in the educational and business sectors. In this regard, Ms. Bezanson cited the example of the European Youth Guarantee program, which ensures that young people have access to continuing education, apprenticeships and/or employment after leaving formal education. In its brief, the Canadian Alliance of Student Associations also raised the idea about a national school-to-work transition strategy.[154] Further, Valérie Roy, Director General at the Regroupement québécois des organismes pour le développement de l’employabilité, called for increased funding for programs such as the Skills Link component of the Youth Employment Training Strategy, for more flexible transfer agreements with the provinces and territories, as well as for the establishment of a career development frame of reference through the Forum of Labour Market Ministers.[155] Similarly, Ms. Hare suggested that the federal government amend the Canada Job Fund Agreements and dismantle the Canada Job Grant program to ensure that funds are allocated towards the training of individuals facing multiple barriers to employment, rather than primarily to the upskilling of those who are already employed. In addition, Ms. Moreau proposed the introduction of an EI training credit to better support the training efforts of small- and medium-sized businesses.[156] Another suggestion made by witnesses included creating work experience opportunities and incentives for students and recent graduates in in-demand sectors of the economy.[157] b. Precarious employmentAccording to Ms. Bezanson, Canada has “the highest rates of post-secondary education degree-holders in the OECD [Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development] who are working in jobs from which they earn half or below half of the median income, which is the commonly accepted cut-off point for poverty.”[158] She also noted that Indigenous and immigrant youth, as well as people with disabilities, face even greater challenges. Combined, precarious forms of employment were described to the Committee as leading to higher rates of youth poverty and to the expansion of the working poor.[159] A reference document submitted by the Canadian Labour Congress indicates the following: Young workers have not fared well over the past three decades in terms of employment and income... Although this can be expected to a degree, since young Canadians may have fewer developed skills and are less likely to be as advanced along their career path, low wages combined with the degradation of job quality raises concerns. Workplaces are changing and although trends like the growth of non-standard working relationships, the growing service sector, globalization and trade liberalization, and technological change present new opportunities, they also threaten to undermine labour laws, employment standards and other safeguards that are in place to protect workers and their communities.[160] Data provided by Ms. Norgang shows that precarious employment has become a norm for young Canadians, with 1 in 4 youth being underemployed and with 1 in 5 youth being in part-time employment involuntarily. What were once entry-level positions have now become long-term jobs. As a result, there has been an increase in the number of youth holding multiple jobs. Ms. Norgang also stated that there has been a “drastic rise” of employers misclassifying workers as self-employed, which has the effect of shifting the costs and risks of owning a business onto the workers themselves and of denying workers basic employment standards such as minimum wage and hours of work. She also noted that, while 37% of workers in their early 50s have a workplace pension plan, only 9% of those in their early 20s do.[161] In a brief submitted to the Committee, YWCA Canada cautioned that the general trend away from full-time permanent employment has impacted men and women differently, and that women are more likely to earn minimum wage and to be engaged in precarious employment than their male counterparts. The brief also noted that the feminization of certain occupations, in particular, has contributed to higher rates of labour force insecurity for women, as these positions are often characterized by lower wages as well as by lack of benefits and job security. Further, according to Kendra Milne, Director of Law Reform at the West Coast LEAF, women in Canada earn less than men in full-time annual earnings; a gap that is larger for Indigenous, disabled and racialized women.[162] According to Ms. Desa, recent immigrants are also more likely to be in precarious employment. At the time of their application for a loan with the Immigrant Access Fund Canada, she noted, 42% of applicants were unemployed and the remaining 58% were in survival jobs. In addition to the barriers identified above with regards to the recognition of foreign credentials, recent immigrants are often required by employers to have Canadian work experience, and are excluded from the social and informational networks that can lead to employment.[163] In order to address precarious employment, the representative from the Canadian Labour Congress recommended that the federal government explore the creation of a youth guarantee program, similar to the one in place in Europe, to guarantee youth either training or employment following the end of formal education, as explained above. While some positive steps have been taken to address precarious-employment related issues, such as the Canada Summer Jobs program, she noted that more needs to be done in this regard. For example, the Canada Summer Jobs program could be extended beyond the summer months and two-tier contracts could be banned. She also suggested that the federal government review and revise employment standards legislation to ensure it addresses the changing nature of the workplace, and that a national poverty reduction strategy developed by the federal government take into account Canada’s diversity in order to ensure equality of opportunity.[164] With respect to the precarious employment of recent immigrants, Ms. Desa recommended that the federal government recognize the role that mentoring and bridging programs can play in supporting immigrants overcome barriers to employment.[165] c. The impact of child care on the employment of womenThough also recognized as a barrier to education and skills training, witnesses appearing before the Committee spoke at length about insufficient affordable and accessible child care as a barrier to women’s full integration into the workforce and as one of the causes of poverty for women. Given its impact on the employment of women, lack of affordable and accessible child care is one of the contributory factors to women having overall lower employment earnings, lower pensionable earnings, as well as lower retirement savings. As a result, women continue to disproportionately live in poverty later in life, with caregiving impacting a woman’s financial security throughout her life. According to Ms. Mile, the median cost of child care in the province of British Columbia is between $1,200 and $1,300 a month, which constitutes the second largest expense for families after housing. Pamela McConnell, Deputy Mayor of the City of Toronto, remarked that, in Toronto, the cost of child care can be as high as $2,350 a month. For women parenting alone, Ms. Milne noted, the cost of child care constitutes an “insurmountable barrier to employment” as they cannot realistically earn enough to afford child care and other basic necessities of life. This, in turn, forces many women to rely on social assistance and other forms of financial dependency. Women parenting as part of a couple, however, also face difficulties with respect to caregiving. Indeed, the high cost of child care means that the lower earning parent, who is often the mother, will sometimes forgo employment in order to fill the gaps in child care or reduce the costs of care. In these situations, if the relationship breaks down, women may be at risk of poverty.[166] In addition to affordability issues around caregiving, some witnesses spoke about the lack of accessible child care. Ms Cattari told the Committee about a high-priority neighbourhood in Hamilton, Ontario, where there were zero licensed child care spaces available and 1,755 children under the age of 12. Further, Tracy O’Hearn, Executive Director for the Pauktuutit Inuit Women of Canada, indicated that there is a “pervasive and chronic lack of child care” in Inuit communities. Witnesses also spoke about the long waiting lists associated with accessing affordable child care. In contrast, Ms. McConnell indicated that Toronto has 4,000 vacant child care spaces despite waiting lists, as they are unaffordable without subsidies.[167] The majority of witnesses who addressed this subject agreed that there is a need for affordable and accessible child care. Ms. Cattari, for example, called for affordable universal child care, with a focus on placing centres in high-priority neighbourhoods; as well as for greater support for community-based, not private, child care centres. In addition, Ms. Milne suggested that federal funding in this regard adhere to human rights and gender principles in order to ensure that the needs of women who live in poverty are met. Witnesses also emphasized the importance of family development within the context of child care, indicating that greater supports for families living in poverty are necessary and that this topic should be addressed alongside the issue of early learning.[168] d. The employment of people with disabilities[169]The Committee was told that the unemployment rate for people with disabilities is extremely high and that, as a result, people with disabilities are twice as likely to live below the poverty line. Data shared with the Committee by the organization Every Canadian Counts reveals that, in 2011, the employment rate for Canadians with disabilities was 49% compared to 79% for non-disabled Canadians.[170] This situation, witnesses explained, is owed to a complex array of misconceptions on the part of employers and society as a whole, as well as ineffective programs for people with disabilities. During his appearance before the Committee, Mark Wafer, Tim Hortons franchisee, suggested that many employers fear that hiring a person with disabilities means hiring an employee who works slower, takes more sick time, requires more supervision, necessitates expensive accommodations, and is less innovative. In his experience, however, the opposite is true. He described some of the benefits of hiring people with disabilities as follows: What we have discovered is that by building capacity and by including people in real jobs for real pay, we are creating a safer workplace. We are creating a more innovative workplace. We are reducing costs by reducing employee turnover, and much more. There is a clear economic case for being an inclusive employer.[171] While the average annual turnover rate in the quick-service sector is approximately 100% to 125%, Mr. Wafer remarked that his turnover rate for the last 10 years has been under 40% owing to the fact that he is an inclusive employer. In 2015, for example, none of his 46 employees with a disability quit their employment, while the turnover rate for the other 200 employees without a disability was 55%.[172] Garth Johnson, Chief Executive Officer at Meticulon, spoke of their experience as an IT consulting firm that hires people with autism, stating autistic individuals are “at a minimum 60% better, more productive, more efficient, [and] more accurate than their typically abled counterparts who they work with.”[173] In addition, they have never failed on a contract, which is rare in the IT consulting world.[174] With respect to accommodating people with disabilities, witnesses noted that the costs are not as high as employers fear. According to Mr. Wafer, 60% of employees with disabilities do not need accommodation at all, while 35% need some form of accommodation that is likely to cost on average $500 or less.[175] In addition to being beneficial to their businesses, witnesses indicated that being an inclusive employer has also had major impacts on the well-being of people with disabilities themselves. Randy Lewis, former Senior Vice-President of Logistics and Supply Chain at Walgreens, shared with the Committee various personal stories of individuals with disabilities hired by this American firm: ... when I was in Connecticut, I talked to a young man who has multiple seizures a day who told me he had been looking for a job for 17 years and had been unsuccessful until then, or the terrific HR manager we got with cerebral palsy, who made all As in graduate school, and had 30 in-person interviews and not a single job offer, or the 50-something man with an intellectual disability who took his first paycheque home and came back the next day and asked his supervisor, “Why did my mom cry?” There are stories like that on and on.[176] Referring to this group as a “massive talent pool,” Mr. Wafer noted that, of all Canadians with disabilities who have graduated in the last five years, 447,000 of them have not found employment. Of this figure, he added, 270,000 have post-secondary education. The representative from Meticulon further illustrated this point by indicating that, for 85% of their employees with autism this constituted their first job, while the other 15% had prior experience in subsistence level jobs.[177] Speaking of the programs available to assist people with disabilities, witnesses indicated that they are “difficult to access, provide inadequate support, and do not transfer between provinces.” According to the brief submitted by the organization Every Canadian Counts, this fragmented system makes caregivers and their dependents vulnerable to poverty. In this regard, John Stapleton, Metcalf Foundation fellow, told the Committee that, while there is a “vast array of programs” for people with disabilities, these programs have actually had the effect of hindering a person’s incorporation into the workforce as a result of claw back provisions. Social assistance, for example, deducts all other forms of income, including wages, workers’ compensation, and EI sickness benefits.[178] Overall, witnesses suggested that a series of measures need to be taken to ensure the removal of barriers to employment for people with disabilities. Mr. Wafer, for example, recommended that the money that is currently being used to provide wage subsidies for employers under the Opportunities Fund for Persons with Disabilities instead be put towards engagement programs to educate the private sector about the benefits of hiring people with disabilities. Similarly, Mr. Johnson suggested that the federal government invest into research projects to study the business returns associated with hiring people with disabilities, thereby motivating private businesses to follow suit. Mr. Stapleton recommended that emphasis be placed on those programs that help with the transition into employment. Finally, in its brief, the organization Every Canadian Counts suggested the creation of a national disability support program, which would have the objective of providing access to homecare, transportation, and assistive devices necessary for disabled people to work.[179] C. Innovative Approaches Linked to Education, Skills Training and EmploymentDuring the course of the study, the Committee received testimony regarding various innovative ideas and projects in the areas of education, skills training and employment. These ideas and projects, which were often portrayed as innovative models that could be implemented at a larger scale to alleviate poverty rates, included:

[106] Department of Finance Canada, Federal Support to Provinces and Territories and Canada Social Transfer. [107] Health Canada, Aboriginal Head Start on Reserve; and Public Health Agency of Canada, Aboriginal Head Start in Urban and Northern Communities. [108] Government of Canada, Canada Student Loans and Canada Student Grants. [109] Government of Canada, Information about Registered Education Savings Plans (RESPs), Canada Education Savings Grant – Overview, Additional Canada Education Savings Grant – Overview, and Canada Learning Bond. [110] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 15 November 2016 (Mary Pichette, Director General, Canada Student Loans Program, ESDC). [111] Canada Revenue Agency, Line 323 – Your tuition, education, and textbook amounts and Line 319 – Interest paid on your student loans. [112] Government of Canada, Post-secondary education; and Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC), Post-Secondary Student Support Program and University and College Entrance Preparation Program. See also HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 15 November 2016 (Paula Isaak, Assistant Deputy Minister, Education and Social Development Programs and Partnerships, INAC). [113] Government of Canada, 2016-17 Report on Plans and Priorities – Section II: Analysis of Programs by Strategic Outcome, Sub-Program 2.1.14: Literacy and Essential Skills. [114] Government of Canada, National Strategy for Financial Literacy – Count me in, Canada. See also HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 15 November 2016, 0855 (Jérémie Ryan, Director, Financial Literacy and Stakeholder Engagement, Financial Consumer Agency of Canada). [115] Government of Canada, Labour Market Development Agreements, Canada Job Fund Agreements, and Canada Job Grant. [116] Government of Canada, Growing the Middle Class, Budget 2016, 22 March 2016, p. 80. [117] Government of Canada, Youth Employment Strategy, Funding: Skills Link, Funding: Opportunities Fund for Persons with Disabilities – Overview, and Aboriginal Skills and Employment Training Strategy. [118] Government of Canada, Growing the Middle Class, Budget 2016, 22 March 2016. [119] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 15 November 2016 (Paula Isaak, Assistant Deputy Minister, Education and Social Development Programs and Partnerships, INAC). [120] Government of Canada, Growing the Middle Class, Budget 2016, 22 March 2016. [121] Ibid. [122] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 15 November 2016, 0910 (Mary Pichette, Director General, Canada Student Loans Program, ESDC). [123] Reference document submitted by Statistics Canada, “Education and Training: Presentation to the Stating Committee on Human Resources, Skills and Social Development and the Status of Persons with Disabilities,” 15 November 2016, pp. 10 to12. [124] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 22 November 2016 (Jennifer Flanagan, Chief Executive Officer, Actua). [125] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 17 November 2016 (Heather Smith, President, Canadian Teachers’ Federation). See also HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 29 November 2016 (Kory Wood, Kikinaw Energy Services). [126] Brief submitted by Living SJ, 1 March 2017. See also HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 17 November 2017 (Rachel Gouin, Director, Research and Public Policy, Boys and Girls Clubs of Canada; and Achan Akwai Cham, Volunteer and Alumna, Boys and Girls Club of Canada). [127] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 9 February 2017 (Shilo Boucher, President and Chief Executive Officer, YMCA of Greater Saint John; and Erin Schryer, Executive Director, Elementary Literacy Inc.). See also HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 17 November 2016 (Rachel Gouin, Director, Research and Public Policy, Boys and Girls Clubs of Canada; and Achan Akwai Cham, Volunteer and Alumna, Boys and Girls Club of Canada). [128] Ibid. See also HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 16 February 2017 (Reagan Weeks, Assistant Superintendent, Alberta Education, Prairie Rose School Division); and HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 15 February 2017 (Jeffrey Bizans, Co-Chair, EndPovertyEdmonton). [129] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 22 November 2016 (Courtney Hare, Manager of Public Policy, Momentum). See also HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 20 October 2016 (Derek Cook, Director, Canadian Poverty Institute). [131] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 15 November 2016 (Heather Dryburgh, Director, Tourism and Centre for Education Statistics, Statistics Canada). See also Reference document submitted by Statistics Canada, “Post-secondary savings is on parents’ radar no matter the household income, 2013.” [133] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 22 November 2016 (Courtney Hare, Manager of Public Policy, Momentum). [134] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 15 November 2016 (Heather Dryburgh, Director, Tourism and Centre for Education Statistics, Statistics Canada). [135] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 24 November 2016 (Bilan Arte, National Chairperson, Canadian Federation of Students). [136] Brief submitted by Canadian Alliance of Student Associations. See also HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 22 November 2016 (Danielle Levine, Executive Director, Aboriginal Social Enterprise Program); and HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 24 November 2016 (Bilan Arte, National Chairperson, Canadian Federation of Students). [138] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 15 November 2016 (Heather Dryburgh, Director, Tourism and Centre for Education Statistics, Statistics Canada); and HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 17 November 2016 (Emily Norgang, Senior Researcher, Canadian Labour Congress). [139] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 24 November 2016 (Bilan Arte, National Chairperson, Canadian Federation of Students). See also Brief submitted by the Canadian Poverty Institute and Brief submitted by Canadian Alliance of Student Associations. [140] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 15 November 2016, 0900 (Jérémie Ryan, Director, Financial Literacy and Stakeholder Engagement, Financial Consumer Agency of Canada). [141] Ibid. See also HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 22 November 2016 (Courtney Hare, Manager of Public Policy, Momentum). [142] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 29 November 2016 (Laura Cattari, Campaign Co-ordinator, Hamilton Roundtable for Poverty Reduction). [143] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 25 October 2016 (Wanda Morris, Chief Operating Officer, Vice-President of Advocacy, Canadian Association of Retired Persons; and Brad Brain, Registered Financial Planner, Brad Brain Financial Planning Inc.). [144] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 22 November 2016 (Danielle Levine, Executive Director, Aboriginal Social Enterprise Program). [145] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 22 November 2016 (Courtney Hare, Manager of Public Policy, Momentum); HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 29 November 2016 (Laura Cattari, Campaign Co-ordinator, Hamilton Roundtable for Poverty Reduction); and HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 25 October 2016 (Wanda Morris, Chief Operating Officer, Vice-President of Advocacy, Canadian Association of Retired Persons; and Brad Brain, Registered Financial Planner, Brad Brain Financial Planning Inc.). [146] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 22 November 2016 (Danielle Levine, Executive Director, Aboriginal Social Enterprise Program). [147] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 16 February 2017, 1030 (Vanessa Desa, Vice-Chair, Board of Directors, Immigrant Access Fund Canada). [148] Ibid. See also Brief submitted by Immigrant Access Fund Canada, 3 March 2017. [149] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 17 November 2016, 0850 (Lynne Bezanson, Executive Board Member, Canadian Council for Career Development). [150] Ibid. [151] Ibid. (Lynne Bezanson, Executive Board Member, Canadian Council for Career Development; and Emily Norgang, Senior Researcher, Canadian Labour Congress). [152] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 22 November 2016, 0855 (Monique Moreau, Director of National Affairs, Canadian Federation of Independent Business). [153] Ibid. (Monique Moreau, Director of National Affairs, Canadian Federation of Independent Business; and Courtney Hare, Manager of Public Policy, Momentum). [154] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 17 November 2016 (Lynne Bezanson, Executive Board Member, Canadian Council for Career Development). See also Brief submitted by Canadian Alliance of Student Associations. [155] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 29 November 2016 (Valérie Roy, Regroupement québécois des organismes pour le développement de l’employabilité). [156] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 22 November 2016, 0855 (Monique Moreau, Director of National Affairs, Canadian Federation of Independent Business; and Courtney Hare, Manager of Public Policy, Momentum). See also Brief submitted by the Canadian Federation of Independent Business, “SME Views on Poverty Reduction Strategies: Presentation to the Standing Committee on Human Resources, Skills and Social Development,” 22 November 2016. [157] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 17 November 2016 (Lynne Bezanson, Executive Board Member, Canadian Council for Career Development). [158] Ibid., 0850. [159] Ibid. [160] Reference document submitted by the Canadian Labour Congress, “Diverse, Engaged, and Precariously Employed: An In-Depth Look at Young Workers in Canada,” August 2016, pp. 5 to 6. [161] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 17 November 2016 (Emily Norgang, Senior Researcher, Canadian Labour Congress). [162] Brief submitted by YWCA Canada, “Reducing Poverty for Women, Girls & Gender Non-Conforming People.” See also HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 1 November 2016 (Kendra Milne, Director, Law Reform, West Coast LEAF). [163] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 16 February 2017 (Vanessa Desa, Vice-Chair, Board of Directors, Immigrant Access Fund Canada). [164] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 17 November 2016 (Emily Norgang, Senior Researcher, Canadian Labour Congress). Two-tier contracts have been described as arrangements characterized by different scales of compensation and benefits, such that new employees may receive lower wages, longer probationary periods, or different pensions and benefits, than workers performing the same job who were hired at an earlier date. These differences may be temporary or permanent. Given that new employees tend to be younger, two-tier contracts create concerns about discrimination on the basis of age. For additional information, please refer to YouthandWork.ca, “Prevailing Conditions, Necessary Choices? Michael MacNeil on Two-Tiered Wages,” 2 October 2012. [165] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 16 February 2017 (Vanessa Desa, Vice-Chair, Board of Directors, Immigrant Access Fund Canada). [166] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 1 November 2016 (Kendra Milne, Director, Law Reform, West Coast LEAF); HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 10 March 2017 (Pamela McConnell, Deputy Mayor, City of Toronto). See also Brief submitted by the Women’s Centre of Calgary, “A Poverty Reduction Strategy Must Address Gender Inequalities,” March 2017. [167] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 29 November 2016 (Laura Cattari, Campaign Co-ordinator, Hamilton Roundtable for Poverty Reduction); HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 13 December 2016 (Tracy O’Hearn, Executive Director, Pauktuutit Inuit Women of Canada); and HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 10 March 2017 (Pamela McConnell, Deputy Mayor, City of Toronto). [168] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 29 November 2016 (Laura Cattari, Campaign Co-ordinator, Hamilton Roundtable for Poverty Reduction); HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 1 November 2016 (Kendra Milne, Director, Law Reform, West Coast LEAF); HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 9 February 2017 (Shilo Boucher, President and Chief Executive Officer, YMCA of Greater Saint John; and Erin Schryer, Executive Director, Elementary Literacy Inc.). [169] Please note that challenges related specifically to mental illness and addiction will be addressed under a separate chapter dedicated to this topic. [170] Brief submitted by Every Canadian Counts, “Alleviating Poverty Among Canadians Living with Chronic Disabilities,” February 2017. [171] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 24 November 2016, 0850 (Mark Wafer, President, Megleen operating as Tim Hortons). [172] Ibid. (Mark Wafer, President, Megleen operating as Tim Hortons). [173] Ibid., 0900 (Garth Johnson, Chief Executive Officer, Meticulon). [174] Ibid. (Garth Johnson, Chief Executive Officer, Meticulon). [175] Ibid. (Mark Wafer, President, Megleen operating as Tim Hortons). [176] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 29 November 2016, 0910 (Randy Lewis, Former Senior Vice-President, Walgreens). [177] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 24 November 2016 (Mark Wafer, President, Megleen operating as Tim Hortons; and Garth Johnson, Chief Executive Officer, Meticulon). [178] Ibid. (John Stapleton, Fellow, Metcalf Foundation). See also Brief submitted by Every Canadian Counts, “Alleviating Poverty Among Canadians Living with Chronic Disabilities,” February 2017. [179] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 24 November 2016 (Mark Wafer, President, Megleen operating as Tim Hortons; Garth Johnson, Chief Executive Officer, Meticulon; and John Stapleton, Fellow, Metcalf Foundation). See also Brief submitted by Every Canadian Counts, “Alleviating Poverty Among Canadians Living with Chronic Disabilities,” February 2017. [180] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 9 February 2017 (Shilo Boucher, President and Chief Executive Officer, YMCA of Greater Saint John; and Erin Schryer, Executive Director, Elementary Literacy Inc.). [181] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 16 February 2017, 0845 (Reagan Weeks, Assistant Superintendent, Alberta Education, Prairie Rose School Division). [182] Ibid. [183] Brief submitted by Mohawk College, “City School by Mohawk’s Impact on Poverty Reduction in Hamilton,” 30 January 2017. [184] Ibid. [185] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 16 February 2017, 1030 (Vanessa Desa, Vice-Chair, Board of Directors, Immigrant Access Fund Canada). [186] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 17 November 2016 (Lynne Bezanson, Executive Board Member, Canadian Council for Career Development). [187] HUMA, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 24 November 2016 (Adaoma C. Patterson, Adviser, Peel Poverty Reduction Strategy Committee). [188] Brief submitted by BUILD Inc., March 2017. [189] Ibid. |