FEWO Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

INTRODUCTION

Canadians are living longer, and the proportion of seniors[1] in the Canadian population is increasing faster than that of any other age group. Women are disproportionately represented among the 65 years and older age group, as shown in Figure 1, and outlive men, on average, by several years.[2] Women born in the 2014-2016 period have a life expectancy of 84 years, compared to 79.9 years for men.[3]

Although women tend to lead longer lives than men in Canada, senior women are more likely than senior men to live with low income, which affects the quality of their lives. Certain groups of senior women, such as Indigenous women, may be particularly vulnerable to live with low income.[4] Beyond income-related challenges, senior women can encounter difficulties related to health and wellness, as well as discrimination, abuse and gender-based violence that may not be experienced by senior men.

Figure 1 - Number of Men and Women Aged 65 Years and Over in Canada, by Age Category (1 July 2018)

Source: Figure prepared using data obtained from Statistics Canada, “Population estimates on July 1st, by age and sex,” Table: 17-10-0005-01 (formerly CANSIM 051-0001), accessed on 3 May 2019.

Recognizing that senior women in Canada face specific challenges, and that these can negatively affect their quality of life, the House of Commons Standing Committee on the Status of Women (the Committee) agreed on 19 June 2018 to undertake a study on the factors contributing to senior women’s poverty and vulnerability in Canada. The Committee adopted the following motion:

It was agreed, — That, pursuant to Standing Order 108(2), the Standing Committee on the Status of Women undertake a study to examine the challenges faced by senior women with a focus on the factors contributing to their poverty and vulnerability, including, but not limited to:

- Access to transportation;

- Access to health services and medication;

- Cost of home and health services;

- Access to affordable housing;

- Access to justice; and

- Widowhood.

That the Committee conduct this study over the course of eight meetings, report its findings to the House, and request a government response to its report.[5]

The Committee received testimony from 54 witnesses, 10 of whom appeared as individuals, 11 as representatives for five federal departments and agencies, and the remainder representing 18 organizations. The Committee was briefed by officials from Statistics Canada, the Public Health Agency of Canada, the Department of Employment and Social Development, the Department for Women and Gender Equality, and the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation. The testimony was received during nine meetings between 21 February and 2 May 2019. Finally, 24 individuals and organizations provided written briefs and speaking notes to the Committee. Appendix A includes a list of all witnesses and Appendix B includes a list of all submitted briefs.

The Committee’s report provides an examination of senior women’s financial security, health and wellness and vulnerability to discrimination and gender-based violence.

Witnesses presented factors that can contribute to senior women’s poverty and vulnerability, as well as to their loss of autonomy. The Committee’s report describes the main factors highlighted by witnesses, including:

- the persistence of the gender wage gap;

- women’s tendency to participate in part-time and unpaid work, including caregiving;

- women’s longer life expectancy compared to men, which can lead to greater physical challenges and financial insecurity;

- the lack of accessibility and availability of affordable housing and transportation;

- insufficient funding for home care and community-based supports;

- the high cost of medication, particularly in combination with other basic needs including food and housing;

- social isolation; and,

- discrimination and gender-based violence.

The Committee believes that any approach to ensuring healthy aging and a good quality of life for Canada’s seniors must include the intersecting perspectives of diverse groups of senior women and must respect senior women’s rights to independence and autonomy. In addition to gender, senior women’s poverty and vulnerability are affected by various aspects of intersecting identities; “women with disabilities, [I]ndigenous women, ethno-cultural minority and immigrant women, and LGBTQ[6] women experience unique challenges as they age.”[7]

The Committee’s report and accompanying recommendations are intended to provide guidance to the Government of Canada on measures that could be implemented to address the factors contributing to senior women’s poverty and vulnerability. The Committee members would like to thank the witnesses who offered their knowledge, ideas and insights to the Committee during its study.

INCREASING SENIOR WOMEN’S ECONOMIC SECURITY

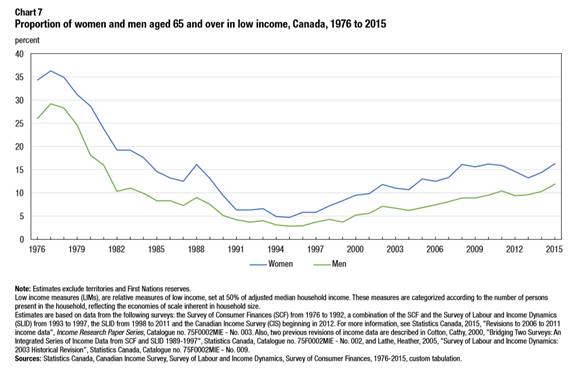

Poverty among seniors in Canada has decreased significantly over the past decades, including for senior women.[8] However, senior women remain more likely than senior men to live on lower incomes and to live in poverty, as shown in Figure 2.[9]

Figure 2 – Proportion of Women Men Aged over 65 years in Low Income (1976 to 2015)

Source: Dan Fox and Melissa Moyser, PhD, “The Economic Well-Being of Women in Canada,” Women in Canada: A Gender-based Statistical Report, 89-503-X, Statistics Canada, 16 May 2018, p. 15.

Senior women’s experiences of vulnerability and poverty are affected by various identity factors such as ethnicity, immigration status, disability, sexual orientation and gender identity and indigeneity.[10] For instance, certain groups of senior women, such as immigrant and Indigenous women as well as women living alone or with non-family members, are at higher risk of living below the poverty line.[11] The Committee was told that although senior women are not a homogenous group, senior Indigenous women share common experiences that affect them as a group: colonization, residential schools, the Sixties Scoop and discriminatory policies that affect health and wellbeing.[12]

Senior women’s poverty “is often a function of events occurring across their lives”[13] and is not related to age alone.[14] Witnesses highlighted several challenges women face throughout their lives that can affect their economic security as seniors:

- Women have lower lifetime employment earnings than men: women generally earn less than men throughout their lives, in part because of the gender wage gap and because women disproportionately occupy lower-paid or part-time jobs.[15]

- Women are at a double disadvantage since they earn less than men over their lifetimes and they live longer than men, on average, thus having to provide for themselves for a longer period of time with lower incomes and smaller savings compared to men.[16]

- Women are more likely than men to perform unpaid care work for their children or for family members, which affects their ability to participate fully in the workforce.[17] Women can carry on this type of work in older age, when they might have to care for their partners, parents or grandchildren.[18] Witnesses stated that caregiving work is not sufficiently recognized and explained that increased financial compensation for this type of work was necessary to limit the impacts it might have on senior women’s economic security.[19]

Representatives from the Department of Employment and Social Development told the Committee about Opportunity for All: Canada’s First Poverty Reduction Strategy (the Strategy) released in August 2018. The federal Strategy establishes an official poverty line based on the market basket measure[20] and establishes poverty reduction targets.[21]

Senior Women’s Income

Senior women’s poverty “is often a function of events occurring across their lives” and is not related to age alone.

Since women earn less than men throughout their lives, they contribute smaller amounts than men to their Canada Pension Plans (CPP) or to their Québec Pension Plans (QPP) and to other savings plans, such as registered retirement savings plans (RRSPs) or tax-free savings accounts (TFSAs). This situation can directly affect senior women’s incomes.[22] One witness explained: “Because of my late entry into the paying workforce, I have not had time to prepare adequately for retirement in terms of CPP or independent workplace retirement plans.”[23] As well, certain groups of senior women who have not been in the Canadian workforce for a long period of time, for instance, some immigrant and refugee women, receive lower CPP payments.[24] Witnesses stressed the need for women to be able to contribute to their CPP or QPP if they work reduced hours, or stay at home full time to do unpaid care work.[25]

The Committee heard about the important value of the choice that some individuals make to stay at home: “Because I stayed at home, I was able to volunteer extensively. I volunteered in my children's schools, at my church and in homeless shelters, and I served on the boards of directors of a number of not-for-profit organizations.”[26] Colleen Young told the Committee:

A young woman today should feel secure in having the choice to stay at home and raise a family or work part- or full-time, if she wishes to, and know that as she ages, she can receive the same deductions and benefits, and maybe even a pension, as her spouse does. Here is where the key lies. Where are her benefits if she chooses to stay home, is unemployed, but plays a key role in the development of her family? No dollar value has ever been assigned to such an important and extremely significant job in this world.[27]

A representative from Statistics Canada indicated that poverty tends to decrease during senior years mainly because of government transfers such as the Old Age Security (OAS) program[28] and the Guaranteed Income Supplement (GIS):[29] “Without these two programs, the poverty rate of seniors would be five times larger than it is now.”[30] OAS and GIS represent a significant proportion of senior women’s total income, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3 – Principal Income Sources for Seniors, as Percentage of Total Income, by Sex (2013)

Note: Abbreviations: Old Age Security (OAS), Guaranteed Income Supplement (GIS), Spouse’s Allowance (SPA), Canada Pension Plan (CPP) and Quebec Pension Plan (QPP).

Source: Figure prepared using data obtained from Tamara Hudon and Anne Milan, “Table 7: Income sources as a percentage of total income of women and men aged 65 and over, Canada, 2003 and 2013,” Senior Women, Women in Canada: A Gender-based Statistical Report, 89-503-X, Statistics Canada, 30 March 2016.

Witnesses stated that benefits received from OAS and GIS are not enough for an individual “to lead a decent life with comfortable housing, adequate food and clothing, health care, let alone participate in social activities and recreational and cultural events, not to mention the costs of transportation and travel.”[31] The cost of living varies greatly across the country, so the fixed amount received through GIS and OAS might not be enough to cover the cost of living in some areas.[32] Some witnesses indicated that the eligibility requirements for OAS, particularly the requirement to have lived in Canada for at least 10 years after the age of 18, can prevent some vulnerable seniors, such as senior immigrants, from accessing the program.[33] Several witnesses recommended that the federal benefits available to caregivers be increased and that the tax credit available to caregivers be refundable.[34]

In a submitted brief, the Réseau FADOQ indicated that seniors often have higher day-to-day expenses than other age groups, because of the cost of medications or assistive devices. To cover these costs, some seniors might have to tap into their RRSPs or registered retirement income funds (RRIFs).[35]

Widowhood can also negatively affect senior women’s income. Outliving one’s spouse can mean losing an important source of income; when a recipient of GIS and OAS dies, the surviving spouse can no longer rely on this source of income to fulfil financial obligations and must then restructure their personal finances.[36] As well, a witness explained that, when they become widowed, women who were not in charge of their household finances, but that now have to take care of their finances, can face a steep learning curve, a problem that may be compounded by the fact that most government services are primarily accessible online.[37]

Witnesses stressed the need for financial literacy training for women to help them carefully plan their retirement.[38] As well, the Committee heard that “helping women understand the roles that different financial mechanisms play across their life course is very important.”[39] Financial literacy training is also important for senior women as they tend to report lower confidence in their financial knowledge than do men.[40] As well, the Committee heard that seniors might need help to understand which government programs are available to them and how to access them.[41]

To help address challenges facing women throughout their lives that can affect their economic security as seniors, the Committee recommends:

Recommendation 1

That the Government of Canada continue to address the pay disparities between men and women in the workforce by placing a priority on pay equity and ensuring more financial security for women later in life.

Recommendation 2

That the Government of Canada ensure that current support and tax credits for caregivers are meeting the needs of families caring for seniors.

Recommendation 3

That the Government of Canada, with the goal of ensuring a financially secure retirement for everyone in Canada and recognizing the value of unpaid caregiving work, create provisions like the drop-out from Employment Insurance in the Canada Pension Plan and/or tax benefits for individuals who stay at home to care for family members, including for those who do so full-time, to participate meaningfully in this contributory program; the definition of caregivers should include spouses, children, grandchildren, and Indigenous Elders.

To help increase the economic security of senior women, particularly for senior women living with low-incomes, the Committee recommends:

Recommendation 4

That the Government of Canada consider making changes to the Guaranteed Income Supplement (GIS) and Old Age Security (OAS) program to improve senior women’s economic security, such as:

- ensuring that senior women who are financially vulnerable, including those who are newcomers to Canada, are aware of and have access to OAS; and

- examining extending GIS benefits of a deceased recipient to a surviving spouse for a few months to allow the surviving spouse to restructure their personal finances.

Recommendation 5

That the Government of Canada examine the development of a Seniors Entrepreneurship Program (possibly through the Women Entrepreneurship Strategy) and provide supports and services to older women to start their own businesses or develop particular skills.

Recommendation 6

That the Government of Canada consider removing the requirement for mandatory minimum withdrawals from Registered Retirement Income Funds that comes into effect at the end of a person’s 71st year to ensure that seniors who choose to work past the age of 70 or who have other sources of income are not required to make the minimum withdrawals.

Recommendation 7

That the Government of Canada examine disability-related benefits and tax measures to ensure that persons living with disabilities are not penalized financially for increasing the number of hours they work in paid employment.

IMPROVING SENIOR WOMEN’S HEALTH AND WELLNESS

[G]ender affects most of the known factors that determine health, including education, occupation, income, social networks, physical and social environments and health services.… The first step in reducing health inequalities in older adult life is reducing socioeconomic disparities, with a focus on gender.[42]

As women age, various factors can affect their health and wellness. Factors such as a lower socioeconomic status,[43] living alone,[44] and frailty[45] disproportionately affect women, and can have negative impacts on their overall health and wellbeing. This section of the report will examine various aspects of senior women’s health, including access to safe and affordable housing, social isolation, specific health concerns, access to prescription drugs and to home care services.

To help improve senior women’s health and wellness, the Committee recommends that:

Recommendation 8

That the Government of Canada continue to apply a gender-based analysis plus lens to the development of all policies and programs related to seniors, and develop programs to address the specific needs of minority women and members of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer and Two-Spirit community.

Recommendation 9

That the Government of Canada work with the National Seniors Council and other stakeholders, including women, to develop a national seniors strategy that addresses the needs of Canada’s senior population, ensures the equitable provision of supports and services across the country, and considers the unique needs of women, minority groups and the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer and Two-Spirit community.

Access to Safe, Accessible and Affordable Housing

Access to safe, accessible and affordable housing is a challenge for many senior women, particularly those living alone or in rural areas, or who have a low income.[46] The Committee heard that 14% of senior-led households are in core housing need. People in core housing need to spend more than 30% of their income on housing. Seniors living on their own are more at risk of being in core housing need and a higher proportion of senior women living alone (27%) than senior men living alone (21%) are in core housing need.[47] Witnesses also told the Committee that they were witnessing an increase in homelessness among older women.[48] The Committee was told about the planned Canada Housing Benefit,[49] which would provide low-income seniors with a $2,500 annual benefit starting in 2020.[50]

The Committee heard about the Government of Canada’s efforts to increase access to safe, accessible and affordable housing through the National Housing Strategy (NHS). The NHS is “focused primarily on vulnerable populations, including seniors, who have special housing needs and often limited financial resources.”[51] A representative from the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) told the Committee that seniors could benefit from affordable housing units and renovation projects funded under the NHS’s National Housing Co-Investment Fund and from investments in community housing stock.[52] The Committee was told that 33% of all investments under the NHS are expected to support the needs of women and girls.[53] However, the Committee was told that funding under the NHS is “going to fall woefully short of what's needed”[54] and that the NHS must “better address the housing needs of older women.”[55]

Witnesses stressed the importance of independent living and of keeping seniors in their homes.[56] For example, Anita Pokiak, Board Member of Pauktuutit Inuit Women of Canada, told the Committee: “I know a lot of the Elders don't like to go into centres. They like their dignity and to be on their own.”[57] Witnesses talked about innovative options that could help seniors stay in or find housing that suits their needs, such as co‑housing, “a form of intentional community where people come together and choose to live in a community,”[58] and universal design, a design that makes housing sustainable and safe as people age.[59] According to a representative from CMHC, “[u]niversal design is built so that, as the population ages, it's really easy to make … adaptations.”[60]

To help senior women live independently and ensure that they can stay in their homes as they age, the Committee recommends that:

Recommendation 10

That the Government of Canada continue to ensure that the specific housing needs of seniors are addressed and prioritized through the National Housing Strategy, with consideration for the intersectional needs of groups such as women, minority communities and members of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer and Two‑Spirit community, and gather data to close the knowledge gap on senior women living alone.

Social Isolation and Loneliness

While the Committee heard that many Canadians wish to stay in their homes and communities as they age, witnesses added that the proper supports must be in place for these seniors, particularly those who live alone. Living alone can contribute to seniors’ social isolation, and as senior women are more likely to live alone, they can be disproportionately affected by social isolation.[61]According to witnesses, other factors contributing to senior’s social isolation include:[62]

- poverty and economic insecurity;

- health concerns, such as chronic pain, disability and mental health troubles;

- history of being subject to discrimination and violence;

- lack of accessible and affordable transportation options, including the loss of one’s driver’s license;

- living in residential care;

- language barriers;

- lack of access to information, particularly digital information, on services available for seniors; and

- lack of funding and resources for community programming for seniors.

Witnesses explained that social isolation can have significant impacts on seniors’ mental and physical health, as well as their quality of life; social isolation can lead to a loss of social connection and self-esteem, an increase in vulnerability to abuse, poor physical and cognitive health, insufficient nutrition, and an increase in seniors’ mortality.[63] However, witnesses emphasized the importance of recognizing that some seniors may choose to live alone and that assumptions that may be informed by ageism should be questioned.[64]

[S]ocial isolation can have significant impacts on seniors’ mental and physical health, as well as their quality of life.

Witnesses emphasized the importance of seniors’ centres, age-friendly communities, volunteer opportunities, access to transportation, telephone outreach services, and community programs to combat seniors’ social isolation.[65] The Government of Canada’s New Horizons for Seniors Program (NHSP) is delivered through Employment and Social Development Canada and provides grants and contributions funding to projects working to empower seniors in their communities. Among the NHSP’s objectives is to support seniors’ social participation and inclusion.[66] Witnesses explained that many effective programs that target various aspects of seniors’ social isolation receive funding through the NHSP, however, that when the funding for these projects ends, so does the project.[67]

Often, as a result of a lack of available health services in many Inuit communities, Inuit seniors are required to move far from their families, cultures and communities to receive care. This move represents a significant loss for the community, as well as an increase in Inuit seniors’ social isolation. The cost and inaccessibility of transportation in remote communities often means that when an Inuit elder moves south to a long-term care facility, their families cannot visit them very often, if at all. This distance from their community and culture can have long-lasting negative impacts on seniors, such as social isolation and loss of culture, and on their home communities, as communities lose their traditional teachers and caregivers.[68]

To address the factors contributing to seniors’ social isolation and access to services, as identified by witnesses, the Committee recommends that:

Recommendation 11

That the Government of Canada continue to support the National Seniors Council to increase awareness and understanding of the social isolation of seniors, and continue the increased funding for the New Horizons for Seniors program to support seniors-driven projects to combat social isolation and help seniors, including senior women living in rural and remote communities and immigrant women, to continue to participate fully in the community.

Recommendation 12

That the Government of Canada, as part of the government’s investment in transportation infrastructure, work with provinces and territories to address the lack of transportation options for seniors living in rural and remote communities.

Senior Women’s Health

The Committee heard that good data is required to develop effective policies and programs to support seniors in Canada. While the Public Health Agency of Canada and Statistics Canada conduct research related to various aspects of Canadian seniors’ experiences, including health and wellbeing, certain gaps in the data exist.[69] For example, both Helen Kennedy of Egale Canada and Chaneesa Ryan of the Native Women’s Association of Canada indicated that health-related research may overlook certain groups of women and senior women, such as “lesbian, [bisexual], transgender, queer, intersex, and Two-Spirit women” and Indigenous women.[70] Furthermore, Statistics Canada identified gaps in its administrative data related to seniors in Canada, such as data on the experiences of individuals living in residential care facilities.[71]

Canada’s aging population means that a greater proportion of Canadians will require specific health care services. Since the prevalence of certain chronic diseases tends to increase with age, it is likely that Canadians 65 years and over live with at least one chronic condition.[72] Since Canadian women tend to live longer than men, they may be more likely than men over their lifetimes to develop a chronic condition or a disability, and encounter complex health challenges as they age.

Witnesses indicated that Indigenous populations tend to experience lower levels of overall wellness when compared to other populations groups in Canada. Furthermore, as they age, Indigenous women are more likely to develop chronic conditions, dementia and/or disabilities earlier in life than non-Indigenous women.[73] Despite the prevalence of these health outcomes among Indigenous populations, access to health services for these conditions may be limited. Chaneesa Ryan of the Native Women’s Association of Canada explained that “44% of first nations people aged 55 and older require one or more continuing care services. However, fewer then 1% have access to long-term care facilities on reserve.”[74]

To help improve senior women’s health, the Committee recommends:

Recommendation 13

That the Government of Canada continue to include lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and two-spirit older and aging individuals in intersectional research that previously only involved women.

Recommendation 14

That the Government of Canada ensure that government-supported research and study of aging and seniors issues apply a gender-based analysis plus lens to gather better data to help guide more informed policy decisions.

Senior Women’s Specific Health Challenges

The Committee heard that among the most prevalent health issues in aging populations are “cardiovascular disease[s], strokes, malignancies, osteoporosis, and cognitive and psychiatric illness.”[75] Senior women are disproportionately affected by both osteoporosis and rheumatoid arthritis when compared to senior men.[76] Similar to the prevalence of chronic conditions, the prevalence of disability increases with age, and is thus higher among women than men over their lifetimes.[77] Finally, mental illness may develop later in life following major life transitions related to aging.[78]

Witnesses identified some specific health challenges and their impacts on senior women’s health and wellbeing, including dental problems, dementia, inadequate nutrition, hearing loss and injuries from falls. Falls pose significant risk to seniors’ overall mental and physical health; of those seniors who experience a fall, close to 20% will die within one year of the fall.[79] Some of these other challenges are detailed in the paragraphs that follow.

Dental care is integral to good overall health. Poor oral hygiene can result in oral diseases; while these diseases are preventable, left untreated they can require costly emergency procedures and potential health complications. Access to dental care can be difficult for seniors who rely on others for care and transportation, as well as for seniors without medical coverage that covers dental costs.[80]

Senior women are more likely than senior men to be diagnosed with dementia.[81] While 7.1% of Canadians suffer from dementia, older women represent approximately two-thirds of this total. The burden of dementia care often falls on women, which can result in elevated mental, physical and financial stress.[82] The Committee heard from a representative of the Public Health Agency of Canada that it is leading the development of a national dementia strategy, which should be released in spring 2019;[83] since women tend to be disproportionately affected by dementia in various ways,[84] this strategy may be particularly relevant for senior women.

Witnesses spoke about certain factors related to aging that may result in the misdiagnosis of seniors’ health conditions. For example, proper nutrition, including access to traditional foods for Indigenous elders,[85] plays a significant role in seniors’ health. Seniors may receive incorrect diagnoses for health problems as a result of cognitive impairments due to poor nutrition, for example, Laura Tamblyn Watts of the Canadian Association of Retired Persons indicated that symptoms resulting from improper nutrition may lead to a senior being inappropriately diagnosed with dementia.[86] Similarly, some health care professionals may not recognize the signs of hearing loss in seniors and may instead provide a diagnosis of cognitive impairment.[87] Stigma, cost, and self-esteem issues may deter seniors from seeking appropriate hearing health services, leading to mental health troubles, social isolation and an increased risk of falls and other health complications among seniors.[88]

To help address senior women’s specific health challenges, the Committee recommends:

Recommendation 15

That the Government of Canada, in collaboration with provinces and territories, ensure equitable access for all seniors to hearing health care and assistive devices, and work with appropriate agencies to increase public awareness to prevent hearing loss, to identify and manage hearing loss and to destigmatize hearing loss.

Recommendation 16

That the Government of Canada continue to build on Canada’s National Dementia Strategy and the work of the Ministerial Advisory Board on Dementia to ensure Canada is tackling the increasing level of dementia in Canada’s aging population.

Recommendation 17

That the Government of Canada develop a strategy to combat the issue of malnutrition for seniors and encourage access to healthy and nutritious food.

Recommendation 18

That the Government of Canada develop culturally specific and appropriate multilingual support services specifically for older women and support the development of orientation programs to help older women and their families navigate the complexities of the justice, immigration and health care systems.

Recommendation 19

That the Government of Canada continue to develop initiatives to promote healthy aging for women, including physical programs and mental health support programs.

Access to Appropriate Health Care

Canada’s health care system often provides various types of care through a combination of providers, and this system may be challenging for seniors to navigate as they age.[89] This situation can be particularly true for First Nation seniors because of the jurisdictional division of First Nations’ health care provision on and off reserve.[90] Access to health services may also vary by region.[91]

With respect to Indigenous seniors, witnesses explained that a large proportion of Indigenous seniors live off-reserve. In accessing health services off-reserve, seniors may encounter racism in the health care system, and may not have access to culturally safe supports in these contexts.[92] To access necessary health services as they age, including mental health and addictions services, some Indigenous seniors may be forced to leave their communities. Leaving their communities, families and cultures can be traumatizing for Indigenous seniors, particularly for survivors of residential schools or the Sixties Scoop who were forced to leave their communities as children.[93]

Other factors were identified by witnesses as being potentially challenging to senior women’s access to health services. For some senior women, language barriers may impede their access to health services. For example, Anglophone senior women living in Quebec may not have access to health services in English in their communities or may not be comfortable describing their health challenges to service providers in French.[94] Furthermore, accessing health services may be a particular challenge for seniors who are living with a disability; lack access to transportation; or have to travel long distances from rural and remote communities to seek medical services.[95] In addition, witnesses suggested that gender differences exist in seniors’ access to, as well as experiences within, the health care system, which can have harmful consequences for senior women.[96]

Witnesses added that health care staff must be properly trained in addressing the health concerns of, and providing proper care to, diverse seniors, including women identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, two-spirit and other identities, as well as Indigenous women and women living with disabilities.[97]

Witnesses emphasized the importance of access to appropriate health services for diverse groups of senior women in their homes and communities. Health care services that are provided close to home and are focused on prevention, including fall prevention, were highlighted as imperative to ensure that seniors stay well and that the prevalence and length of hospital stays are reduced.[98]

To help ensure senior women’s access to appropriate health care, the Committee recommends:

Recommendation 20

That the Government of Canada provide funding to ensure access to services that meet the mental health needs of diverse groups of seniors, including members of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer and Two-Sspirit communities, as well as women living with disabilities and Indigenous women, and work with provincial and territorial governments to ensure that diverse groups of seniors have access to safe spaces in health care settings.

Access to Prescription Medication and to End-of-Life Medical Care

The Committee heard concerns related to prescription drugs, as well as to the provision of medical assistance in dying for senior women. The cost of medication is a concern for many seniors, and senior women may be disproportionately affected by these costs.[99] Witnesses suggested that there are significant gaps in the coverage of pharmaceutical drug costs by public insurance plans across Canada, and many seniors may not have private coverage.[100] Seniors living in lower income situations may have to choose between paying rent and buying food or purchasing their medications.[101] Witnesses emphasized the need for a universal pharmacare program to reduce the cost of medication for seniors.

In addition to the cost of medication, witnesses highlighted several other concerns related to prescription drugs. Firstly, if a senior is receiving care from various health care providers, there may not be a clear overview or coordination of the assortment of drugs they are taking.[102] In addition, there may be misunderstanding or confusion about how to take various medications safely, as such, it is important for health care professionals to ensure that senior patients receive information in clear and accessible ways.[103]

Regarding medical assistance in dying, Bonnie Brayton of the DisAbled Women’s Network of Canada suggested that legislative changes introduced to permit medical assistance in dying in Canada may leave women living with disabilities vulnerable to abuse because of a lack of standards and monitoring mechanisms. She explained that women living with disabilities might consider medically assisted dying because of a lack of access to palliative care as well as to other services and supports that could improve their quality of life. She indicated that providing, and guaranteeing access to, these services would ensure that women living with disabilities have options other than medically assisted dying.[104]

To help senior women with the costs of prescription drugs the Committee recommends that:

Recommendation 21

That the Government of Canada pursue options to help seniors and Canadians with the high cost of prescription drugs, including a national pharmacare program, and ensure that the development and implementation of a national pharmacare plan takes into consideration the specific needs of senior women, including financial barriers from out-of-pocket payments for medication.

Availability of Home Care and Support Services

Witnesses highlighted the importance of seniors staying in their homes and communities, instead of in long-term care homes or hospitals.[105] In addition to contributing positively to seniors’ wellbeing, living at home and using home care services may also be more cost-efficient than long-term hospital care.[106] However, home care services can be difficult to access for seniors, and may not meet the diverse needs of Canadian seniors.[107]

Senior women are more likely to receive paid or unpaid support, predominantly with transportation, than senior men.[108] However, according to Statistics Canada, approximately twice the number of senior women have unmet care needs compared to senior men.[109]

The lack of funding for home care was identified as a factor contributing to insufficient and inconsistent home care across the country. In Inuit communities, many health care services and resources are unavailable, including sufficiently trained home care staff, and culturally appropriate palliative care.[110] Indigenous senior women may require specific services and care to address the effects of “unhealed historic trauma” and other adverse experiences, which may not be available in their communities.[111]

Without home care services, seniors may be vulnerable to various health challenges, including falls, poor nutrition and mental health troubles.[112] In the absence of accessible home care services, women’s unpaid caregiving and labour often fills the gaps. Women of all ages continue to bear a disproportionate amount of caregiving responsibilities; “[s]enior women are more apt to receive unpaid help from their daughters, while for senior men it more often comes from their spouse.”[113] As indicated earlier in this report, women’s caregiving responsibilities can affect their economic security, as well as their health, across their lifetimes.

To ensure that all senior women have access to appropriate home and community care services, the Committee recommends that:

Recommendation 22

That the Government of Canada, in collaboration with the provinces and territories, examine issues of diversity in access to home and community care, with particular consideration for the unique needs of diverse senior women, to ensure that their specific home and community care needs are met.

Recommendation 23

That the Government of Canada work with Northern and Indigenous communities to improve access to culturally sensitive and appropriate long-term, residential and palliative care facilities in their communities, and work to ensure that, when Elders must leave their community for care, they have access to culturally appropriate food and community support.

ELIMINATING DISCRIMINATION AND VIOLENCE AGAINST SENIOR WOMEN

The Committee heard that ageism, “a combination of prejudicial attitudes towards older people, old age and aging itself,”[114] can greatly affect senior women’s lives. Senior women may be ignored, underestimated or patronized, which can create barriers for them to overcome with regards to body image, health, finances and justice.[115] Ageism can also negatively affect government policy decisions, development and implementation.[116]

Women can experience discrimination and gender-based violence at any time of their lives, including in their senior years, and the effects of violence “can accumulate, creating compound effects of violence experienced through the life stages.”[117] Senior women’s experiences of discrimination and violence can be compounded by several identity factors, such as age, sexual orientation and disability.[118] Indeed, the Committee heard that “[o]lder women's lives are often impacted by the dual effects of sexism and ageism.”[119] Other factors can increase senior women’s risk of experiencing violence such as living with a disability, widowhood, dependence on a caregiver, or socio-economic conditions.[120] As well, senior women who are sponsored immigrants might have no choice but to stay with family members who are financially responsible for them, a situation which “sets up a dynamic of deep concern about abuse and neglect.”[121] The strategy, It’s Time: Canada’s Strategy to Prevent and Address Gender-Based Violence was launched in 2017, and aims to address gender-based violence and gaps in support for diverse groups experiencing gender-based violence, including senior women.[122]

[O]lder women's lives are often impacted by the dual effects of sexism and ageism.

A common form of violence against senior women is financial abuse. Because technology evolves quickly and can sometimes be difficult to master, especially with regards to online banking, seniors who are less “tech-savvy” might be vulnerable to fraud or scams.[123] Other examples of financial abuse against seniors can include misuse of power of attorney, being forced to sign legal papers one does not understand or being forced to give money to relatives.[124] The Committee was told that in Inuit communities, Inuit Elders are often the leaseholders of social housing; as such they may be vulnerable to family members taking advantage of this situation by moving in and not contributing to household costs.[125] Educating seniors on how to protect themselves to avoid being victims of financial abuse, particularly online, and raising awareness of the signs of financial abuse among seniors is important.[126] Certain elder abuse prevention projects receive funding through the Government of Canada’s New Horizons for Seniors Program, which is administered by Employment and Social Development Canada.[127]

The Committee was told that senior women who are victims and survivors of violence might be ashamed or afraid to ask for help. To that end, confidential phone services can help them assess their situation, evaluate their options, and move forward.[128] As well, senior women face barriers when trying to seek help when they are victims and survivors of violence, including a lack of services adapted to the needs of seniors, social isolation, and cultural or language barriers.[129] Some senior women experiencing violence may be reluctant to go to a shelter or a transition house because they might have to move far away from their friends and families to access these services, or because shelters and transition houses are not adapted to their needs.[130]

Also, witnesses stated that senior women can face barriers accessing legal services because of a lack of financial resources or because they might not know where to find a lawyer.[131] Some groups of senior women can face additional barriers in accessing justice. For example, rates of prosecution and conviction of sexual assault of senior women in institutional settings are very low.[132]

In order to help eliminate discrimination and gender-based violence against senior women, the Committee recommends:

Recommendation 24

That the Government of Canada examine the experience of other countries that have appointed either a seniors’ advocate or seniors’ ombudsman, and whether this office would be beneficial in Canada.

Recommendation 25

That the Government of Canada recognize the issue of ageism that exists in our society and adversely affects the senior population and develop a strategic campaign to work to end this stigma in Canada.

Recommendation 26

That the Government of Canada develop programs to raise awareness of elder abuse and ensure that seniors are aware of the resources and support that are available to them.

Recommendation 27

That the Government of Canada work with its provincial and territorial partners to ensure that culturally and age-appropriate services, including shelters and transition houses as well as legal aid, are available for all senior women who experience any form of violence, regardless of where they live.

[1] The term “seniors” is used by the Government of Canada and is therefore used by the Committee in this report. The Committee uses the term to describe individuals in Canada aged 65 years and older, unless otherwise indicated. The Committee acknowledges that the term “seniors” can sometimes carry ageist connotations.

[2] House of Commons Standing Committee on the Status of Women (FEWO), Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 21 February 2019, 0950 (Anne Milan, Chief, Labour Statistics Division, Statistics Canada); and 1035 (Sébastien Larochelle-Côté, Editor-in-chief, Insights on Canadian Society, Statistics Canada).

[3] Statistics Canada, “Life expectancy and other elements of the life table, Canada, all provinces except Prince Edward Island,” Table 13-10-0114-01, accessed 18 April 2019.

[4] FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 21 February 2019, 0945 (Danielle Bélanger, Director, Strategic Policy, Policy and External Relations Branch, Department for Women and Gender Equality).

[5] FEWO, Minutes of Proceedings, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 19 June 2018.

[6] Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer.

[7] FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 2 April 2019, 0945 (Krista James, National Director, Canadian Centre for Elder Law).

[8] Women Focus Canada Inc., “Dr. Oluremi (Remi) Adewale – Women Focus Canada,” Submitted Brief.

[9] See for example: FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 4 April 2019, 0850 (Katherine Scott, Senior Researcher, Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives); and FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 28 February 2019, 0855 (Luce Bernier, President, Association québécoise de défense des droits des personnes retraitées et préretraitées); and FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 30 April 2019, 0850 (Michael Udy, President, Seniors Action Quebec).

[10] Canadian Centre for Elder Law, “Brief,” Submitted Brief, 28 March 2019; and FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 4 April 2019, 0850 (Katherine Scott).

[11] FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 4 April 2019, 0850 (Katherine Scott); and FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 21 February 2019, 0950 (Anne Milan).

[12] FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 2 May 2019, 0910 (Chaneesa Ryan, Director of Health, Native Women's Association of Canada).

[14] FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 30 April 2019, 0845 (Lia Tsotsos, Director, Centre for Elder Research, Sheridan College).

[15] See for example: Women Focus Canada Inc., “Dr. Oluremi (Remi) Adewale – Women Focus Canada,” Submitted Brief; The Interior BC Council on Aging, “Status of Women Brief: Older Women/Poverty/Vulnerability,” Submitted Brief; 2019; FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 4 April 2019, 0855 (Margaret Gillis, President, International Longevity Centre) and 0855 (Katherine Scott); and FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 2 May 2019, 0915 (Chaneesa Ryan).

[16] FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 4 April 2019, 0855 (Margaret Gillis) and 0855 (Katherine Scott).

[17] FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 21 February 2019, 0845 (Jackie Holden, Senior Director, Seniors Policy, Partnerships and Engagement Division, Income Security and Social Development Branch, Department of Employment and Social Development); and FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 2 May 2019, 0915 (Chaneesa Ryan).

[19] See for example: FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 4 April 2019, 1000 (Mary Moody, as an individual) and 1000 (Lana Schriver, as an individual); FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 11 April 2019, 1025 (Oluremi Adewale, Chief Executive Officer, President, Founder, Women Focus Canada Inc.) and 1025 (Amanda Grenier, Professor, McMaster University, as an individual); and FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 30 April 2019, 0950 (Colleen Young, as an individual) and 0955 (Juliette Noskey, as an individual).

[20] There are many ways to measure poverty. In their testimony, Statistics Canada and the Department of Employment and Social Development used the market basket measure, which measures poverty based on the price of a basket of goods and services that an individual requires to meet basic needs and achieve a modest standard of living. See: FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 21 February 2019, 1015 (Sébastien Larochelle-Côté).

[22] See for example: FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 2 April 2019, 1000 (Gisèle Tassé-Goodman, Vice-President, Réseau FADOQ); FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 9 April 2019, 1025 (Laura Tamblyn Watts, Chief Public Policy Officer, Canadian Association of Retired Persons); The Interior BC Council on Aging, “Status of Women Brief: Older Women/Poverty/Vulnerability,” Submitted Brief, 2019; and FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 4 April 2019, 0955 (Mary Moody).

[24] Canadian Research Institute for the Advancement of Women, “Written submission from the Canadian Research Institute for the Advancement of Women to the House of Commons Standing Committee on the Status of Women for its study on challenges faced by senior women,” Submitted Brief, 28 March 2019.

[25] See for example: FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 2 April 2019 0945 (Krista James, National Director, Canadian Centre for Elder Law); FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 4 April 2019, 1000 (Lana Schriver); and FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 4 April 2019, 1000 (Mary Moody).

[26] FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 2 May 2019, 1005 (Shirley Allan, as an individual).

[28] The OAS is a pension program available to Canadians over 65 years old, who have lived in Canada for 10 years or more. The OAS is funded through the federal government’s general tax revenues.

[29] A benefit under the OAS, the GIS provides an additional monthly benefit to OAS recipients who have a low income and are living in Canada.

[31] Coalition citoyenne pour mieux vivre et mieux vieillir, “Recommendations to the House of Commons Committee Situation of Senior Women,” Submitted Brief, 20 March 2019; and Congress of Union Retirees of Canada, “Brief to the House of Commons Standing Committee on the Status of Women, on the Challenges Faced by Senior Women,” Submitted Brief, 20 March 2019.

[34] See for example: FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 2 April 2019, 1000 (Gisèle Tassé-Goodman); and FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 28 February 2019, 1015 (Laura Kadowaki, Policy Researcher, West Coast, Canadian Association of Retired Persons) and 0900 (Luce Bernier).

[35] Réseau FADOQ, “Brief—Challenges Facing Senior Women in Canada,” Submitted Brief, 28 February 2019.

[36] FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 28 February 2019, 0900 (Danis Prud'homme); and FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 2 April 2019, 1000 (Gisèle Tassé-Goodman).

[38] FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 9 April 2019, 1025 (Laura Tamblyn Watts); and YWCA Hamilton, “Challenges Faced by Senior Women with a Focus on the Factors Contributing to Their Poverty and Vulnerability,” Submitted Brief, 2019.

[40] The Interior BC Council on Aging, “Status of Women Brief: Older Women/Poverty/Vulnerability,” Submitted Brief, 2019.

[42] Women Focus Canada Inc., “Dr. Oluremi (Remi) Adewale – Women Focus Canada,” Submitted Brief.

[43] Ibid.

[45] Canadian Frailty Network, “Addressing Challenges Faced by Senior Women,” Submitted Brief, March 2019.

[46] FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 21 February 2019, 0845 (Jackie Holden); and Ontario Association of Interval and Transition Houses, “Challenges Faced by Senior Women,” Submitted Brief, 28 March 2019.

[47] FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 21 February 2019, 0855 (Charles MacArthur, Senior Vice-President, Assisted Housing, Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation).

[48] FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 4 April 2019 0900 (Margaret Gillis); and YWCA Hamilton, “Challenges Faced by Senior Women with a Focus on the Factors Contributing to Their Poverty and Vulnerability,” Submitted Brief, 2019.

[49] The Government of Canada announced the creation of the Canada Housing Benefit (CHB) in November 2017 as part of the National Housing Strategy. The CHB is scheduled to be launched in 2020. For more information, see: Government of Canada, Canada’s National Housing Strategy: A Place to Call Home.

[51] Ibid., 0850.

[52] Ibid., 0855.

[53] Ibid.

[55] Ibid., 0900 (Margaret Gillis).

[57] FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 9 April 2019, 1010 (Anita Pokiak, Board Member, Pauktuutit Inuit Women of Canada).

[59] FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 21 February 2019, 0915 and 0920 (Charles MacArthur).

[60] Ibid., 0915.

[61] FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 30 April 2019, 0855 (Michael Udy); FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 26 February 2019, 0950 (Lori Weeks); and FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 11 April 2019, 0945 (Oluremi Adewale).

[62] See for example: FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 11 April 2019, 1035 (Amanda Grenier); DisAbled Women’s Network of Canada, “Parliamentary Brief,” Submitted Brief, 29 March 2019; FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 21 February 2019, 0945 (Danielle Bélanger); Ontario Association of Interval and Transition Houses, “Challenges Faced by Senior Women,” Submitted Brief, 28 March 2019; and FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 30 April 2019, 0900 (Vanessa Herrick, Executive Director, Seniors Action Quebec) 0850 (Lia Tsotsos).

[63] See for example: FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 21 February 2019, 0845 (Jackie Holden); FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 4 April 2019, 0900 (Margaret Gillis) and 0930 (Katherine Scott); and FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 28 February 2019, 1015 (Madeleine Bélanger, as an individual).

[65] See for example: FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 21 February 2019, 1000 (Anna Romano, Director General, Centre for Health Promotion, Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention Branch, Public Health Agency of Canada); Transportation Options Network for Seniors, “Women & Transportation in Manitoba,” Submitted Brief; Saskatoon Services for Seniors, “Challenges Facing Senior Women in Canada,” Submitted Brief, 29 March 2019; and YWCA Hamilton, “Challenges Faced by Senior Women with a Focus on the Factors Contributing to Their Poverty and Vulnerability,” Submitted Brief, 2019.

[66] Government of Canada, New Horizons for Seniors Program.

[70] FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 2 May 2019, 0910 (Helen Kennedy, Executive Director, Egale Canada); and 940 (Chaneesa Ryan).

[74] Ibid., 0920.

[77] DisAbled Women’s Network of Canada, “Parliamentary Brief,” Submitted Brief, 29 March 2019.

[79] Ibid.

[80] Canadian Dental Hygienists Association, “Submission to the Standing Committee on the Status of Women, Regarding Challenges Faced by Senior Women in Canada,” Submitted Brief, 29 March 2019; and FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 11 April 2019, 1035 (Oluremi Adewale).

[86] Ibid., 1020 (Laura Tamblyn Watts).

[87] FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 26 February 2019, 0845 (Jean Holden, Advisory Board Member, Hearing Health Alliance of Canada) and 0850 (Valerie Spino, Advisory Board Member, Hearing Health Alliance of Canada); and Cathy Cuthbertson, “Brief,” Submitted Brief.

[88] Ibid.

[89] FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 2 April 2019 0945 (Krista James); and FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 2 May 2019, 0935-0940 (Kathy Majowski, Board Chair, Canadian Network for the Prevention of Elder Abuse).

[90] FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 26 February 2019, 1000 (Tania Dick, Vancouver Island Representative, British Columbia, First Nations Health Council); and FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 2 May 2019, 0920 (Chaneeesa Ryan).

[91] Ibid.

[93] FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 2 May 2019, 0920 (Chaneeesa Ryan) and 925 (Roseann Martin, Elder, Native Women’s Association of Canada).

[95] See for example: FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 26 February 2019, 1000 (Tania Dick); Assaulted Women’s Helpline and Seniors Safety Line, “Challenges Faced by Senior Women,” Submitted Brief, 29 March 2019; Coalition for Healthy Aging in Manitoba, “Challenges Faced by Senior Women,” Submitted Brief, 29 March 2019; DisAbled Women’s Network of Canada, “Parliamentary Brief,” Submitted Brief, 29 March 2019.

[97] See for example: FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 4 April 2019, 0915 (Katherine Scott); FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 2 April 2019, 1000 (Philippe Poirier-Monette, Collective Rights Advisor, Provincial Secretariat, Réseau FADOQ); FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 30 April 2019, 0925 (Vanessa Herrick); FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 2 May 2019, 0910 (Helen Kennedy).

[98] FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 4 April 2019, 0915 (Kiran Rabheru, Board Chair, International Longevity Centre Canada); FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 30 April 2019, 0935 (Lia Tsotsos).

[100] Ibid.

[101] Ibid.; and 1020 (Mary Moody).

[104] FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 2 May 2019, 0930-0935 (Bonnie Brayton, National Executive Director, DisAbled Women’s Network of Canada).

[105] Selma Tobah, “Brief submitted to the House of Commons Standing Committee on the Status of Women,” Submitted Brief, 21 March 2019; FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 9 April 2019, 1000 (Anita Pokiak); and FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 26 February 2019, 1005 (Tania Dick).

[106] FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 4 April 2019, 0945 (Kiran Rabheru); and Selma Tobah, “Brief submitted to the House of Commons Standing Committee on the Status of Women,” Submitted Brief, 21 March 2019.

[108] FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 21 February 2019, 0955 (Anne Milan); and FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 4 April 2019, 0910 (Katherine Scott).

[109] Selma Tobah, “Brief submitted to the House of Commons Standing Committee on the Status of Women,” Submitted Brief, 21 March 2019; and Women Focus Canada Inc., “Dr. Oluremi (Remi) Adewale – Women Focus Canada,” Submitted Brief.

[111] FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 28 February 2019, 1030 (Catherine Twinn, Lawyer, as an individual).

[112] Ibid.; and Saskatoon Services for Seniors, “Challenges Facing Senior Women in Canada,” Submitted Brief, 29 March 2019.

[113] FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 21 February 2019, 0955 (Anne Milan); and FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 4 April 2019, 0910 (Katherine Scott).

[115] Ibid; FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 26 February 2019, 0950 (Lori Weeks); and The Interior BC Council on Aging, “Status of Women Brief: Older Women/Poverty/Vulnerability,” Submitted Brief, 2019.

[116] Coalition for Healthy Aging in Manitoba, “Challenges Faced by Senior Women,” Submitted Brief, 29 March 2019.

[118] FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 21 February 2019, 0945 (Danielle Bélanger); National Pensioners Federation, “Submission by the National Pensioners Federation to the House of Commons Standing Committee on the Status of Women: Challenges faced by senior women contributing to their poverty and vulnerability,” Submitted Brief, 25 March 2019; and FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 2 May 2019, 0905 (Helen Kennedy).

[120] The Interior BC Council on Aging, “Status of Women Brief: Older Women/Poverty/Vulnerability,” Submitted Brief, 2019; FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 9 April 2019, 0945 (Anita Pokiak); FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 2 May 2019, 0850 (Kathy Majowski) and 0855 (Bonnie Brayton).

[124] The Interior BC Council on Aging, “Status of Women Brief: Older Women/Poverty/Vulnerability,” Submitted Brief, 2019.

[126] FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 28 February 2019, 0915 (Danis Prud'homme); FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 11 April 2019, 1030 (Oluremi Adewale); and Association québécoise de défense des droits des personnes retraitées et préretraitées, “Brief submitted to the House of Commons Standing Committee on the Status of Women, Ottawa Chaired by Ms. Karen Vecchio,” Submitted Brief, 28 February 2019.

[128] Assaulted Women’s Helpline and Seniors Safety Line, “Challenges Faced by Senior Women,” Submitted Brief, 29 March 2019.

[129] Ibid.

[130] FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 2 April 2019, 0945 (Krista James); and FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 9 April 2019, 1005 (Laura Tamblyn Watts).

[131] FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 2 April 2019, 0950 (Krista James); and FEWO, Evidence, 1st Session, 42nd Parliament, 4 April 2019, 0925 (Margaret Gillis).

[132] DisAbled Women’s Network of Canada, “Parliamentary Brief,” Submitted Brief, 29 March 2019.