CIMM Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

IMMIGRATION TO ATLANTIC CANADA: MOVING TO THE FUTUREPrefaceOn 2 November 2016, the House of Commons agreed to the motion, Private Members’ Business M-39, which instructed the Standing Committee on Citizenship and Immigration (hereafter referred to as “the Committee” or “CIMM”) to undertake a study on immigration to Atlantic Canada. The Committee should consider, among other things, (i) the challenges associated with an aging population and shrinking population base, (ii) retention of current residents and the challenges of retaining new immigrants, (iii) possible recommendations on how to increase immigration to the region, (iv) analysis of the Atlantic Immigration Pilot initiatives associated with the Atlantic Growth Strategy; and that the Committee report its findings to the House within one year of the adoption of this motion.[1] The Committee decided[2] to hold ten meetings on the topic of immigration to Atlantic Canada. From 29 May 2017 to 19 October 2017, the Committee heard from 55 witnesses and received 10 written submissions.[3] IntroductionIn July 2016, the Government of Canada and the four Atlantic Provinces (New Brunswick (N.B.), Nova Scotia (N.S.), Prince Edward Island (P.E.I) and Newfoundland and Labrador (N.L.)) launched the Atlantic Growth Strategy,[4] which aims to “bring stable and long-term economic prosperity in Atlantic Canada.”[5] The strategy focuses on “five areas aimed at stimulating economic growth in the region,”[6] including immigration and developing and retaining a skilled workforce. As part of this recognition of immigration as an important pillar for economic growth, the federal government and provincial partners announced in July 2016 the development of the Atlantic Immigration Pilot Program (AIPP)[7], which was implemented between July and December 2016 and launched in March 2017 under the larger Strategy.[8] In order to understand the need for immigration to Atlantic Canada, this report begins with an overview of the challenges in Atlantic Canada associated with an aging population that is also impacted by outmigration and a shrinking labour workforce that is not naturally renewed, which has persisted for decades. There have been fewer newcomers generally to this region than in the rest of Canada, with urban centres faring better than rural areas. However, labour and skills shortages in a variety of sectors have not attracted more newcomers to the region, which has had an impact on the provinces’ tax bases and on their capacity to deliver social services. To address these challenges both the public sector and the private sector have sought to find solutions through immigration. The report describes the immigration programs available to Atlantic Canada (the Atlantic Immigration Pilot Program, the Provincial Nominee Program, and Express Entry for high-skilled immigration), as well as the specific challenges that each present for the applicant or the employer. Temporary residents, such as international students or temporary foreign workers, are already in the region in significant numbers but there are questions as to which programs can help them best transition to permanent residence. Attracting immigrants to live permanently in Atlantic Canada requires outreach on a number of levels. Not many foreign nationals[9] outside of Canada are aware of the benefits of living in Atlantic Canada. Additionally, once they arrive, there needs to be adequate support from provincial governments, municipalities, settlement services providers, multi-ethnic associations, employers and local communities. Immigration programs, both traditional programs and the new Atlantic Immigration Pilot Program, must also include consultations with businesses to determine what their labour demands are and how to meet them. Employers participating in the Atlantic Immigration Pilot Program are required to provide a settlement plan for each new employee. Although challenging, this business engagement is seen as a pivotal element to successful integration and retention. Other elements essential to retention include welcoming communities, culturally, ethnically or religiously specific community infrastructure and the full recognition of the importance of the family unit and its well-being. Part 1: Understanding the Challenges in Atlantic CanadaCanada currently has a population of approximately 35,152,000 people.[10] Using the results of the 2016 Census of Population, Statistics Canada analyzed population size and growth in Canada, which has increased tenfold since 1867.[11] “[T]he country's population growth has not been constant over those 150 years”[12] and varies greatly depending on the region. In addition, the growth pattern has changed from natural increase[13] to migratory increase.[14] Fertility rates have gradually decreased after the baby boom period and the “migratory increase became the key driver of population growth at the end of the 1990s.”[15] These population changes have many implications for Canadian society, namely for its economy, regional density as well as ethnocultural and linguistic composition. As the Committee heard during the course of its study, Canada’s four Atlantic Provinces have seen a huge variation in population growth over the decades. From 1851 to 1951, the population of Atlantic Canada grew to be about 14% of the country’s population.[16] During the baby boom period, each province in Atlantic Canada had a high fertility rate that ranged from 4.8 to 5.1 children for every woman aged 15 to 64.[17] However, during the decades following 1960 and 1970, nearly half of those baby boomers left the region,[18] which put the Atlantic region on its current trend of slower population growth than the national average. In 2016, Atlantic Canada’s population was 6.6% of Canada’s population.[19] According to Statistics Canada, the slower population growth in Atlantic Canada is mainly due to three factors: lower natural increases, lower immigration levels and higher interprovincial migration.[20] As a result of lower population growth, “the share of Canadians living in the Atlantic region has decreased in the last five decades”[21] affecting the region’s economic prosperity and social composition. Part 1 of the report discusses demographic and labour demand challenges in Atlantic Canada, including a shrinking labour workforce and regional disparities in areas such as social services. It also provides an overview of specific sectors that are employing foreign nationals in Atlantic Canada. A. An aging population and a shrinking labour workforceA number of witnesses spoke of the decline in population in the Atlantic region, as well as labour market shortages for skilled labour.[22] They noted that the negative effects of the decline in population on the economy could not be mitigated by an increase in productivity or innovation.[23] The Committee heard that the effects of an aging population are well-known, including a decrease in demand for goods and a decrease in tax revenue,[24] making it more difficult for provincial governments to provide education and health services.[25] 1. Demographic challengesData from the 2016 Census of Population indicates that the population of Atlantic Canada is declining in the 15 to 64 age range as the number of senior citizens rises.[26] As Mr. Laurent Martel from Statistics Canada pointed out one out of five individuals living in the Atlantic Provinces is now 65 and over.[27] He compared the statistic to other provinces such as Alberta, where only 12% of its population is 65 and over.[28] Professor Ather Akbari, Atlantic Research Group on Economics of Immigration, Aging and Diversity at Saint Mary's University, provided a ten-year overview of the age distribution of the population nationally and in the region by province, as seen in Table 1. Table 1 – Age Distribution of Population, Canada and Atlantic Canada, 2007 and 2017 (%)

Source: Table submitted to the Committee by Ather H. Akbari, Population Aging and Immigration in Atlantic Canada. According to his analysis, the population in Atlantic Canada that is over 65 years old has increased by 5.17% over the last ten years, whereas nationally there was only a 3.46% increase. In addition, Atlantic Canada is facing a decline in birth rates, lower than the national average,[29] and a long-standing trend of young residents leaving the region to settle and work elsewhere.[30] Mr. Martel observed that of these young adults in the Atlantic Provinces it was mostly those who live in rural areas that seem to be leaving in a significant way to settle elsewhere in their province or in Canada.[31] He is of the opinion, however, that these migratory losses of young adults do not exist in the Prairie Provinces, for example. He suggested that there are many demographic factors in the Atlantic Provinces related to retention of young adults (particularly from those in their early twenties to about 28 years old).[32] Finally, witnesses were concerned with the fact that New Brunswick's population has declined by 0.5% since 2011, meaning deaths are now outnumbering births, which is a first in Canadian history.[33] Mr. Martel also cautioned that this population decline “trend … will increase in coming years.”[34] 2. Low numbers of newcomers in Atlantic Canada compared to the rest of CanadaStatistics show that Atlantic Canada receives only a small share of immigrants in proportion to its population. In 2016, New Brunswick, with a population of approximately 730,710 people, had an immigrant population of 4.6%, whereas 21.9% of Canada’s population was composed of immigrants.[35] Nova Scotia’s population was about 908,340 people and had 6.1% of immigrants. In P.E.I., there were 139,685 people and 6.4% identify as immigrants. In Newfoundland and Labrador, 2.4% of the province’s population (521,250) identified as immigrants.[36] Based on data from the 2016 Census, Table 2 illustrates the share of immigrants in Atlantic Canada in proportion to the region’s population and Table 3 provides an overview of the percentage of immigration livening in Atlantic Canada by period of arrival to Canada. Table 2 – Population of Atlantic Canada in 2016 by Non-Immigrants, Immigrants and Non-Permanent Residents Categories

Source: Table complied by the authors using Statistics Canada, “Immigration and Ethnocultural Diversity Highlight Tables”, 2016 Census, Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 98-402-X2016007, Ottawa, 2017.

Table 3 – Percentage of Immigrants Living in Atlantic Canada in 2016 by Period of Arrival to Canada

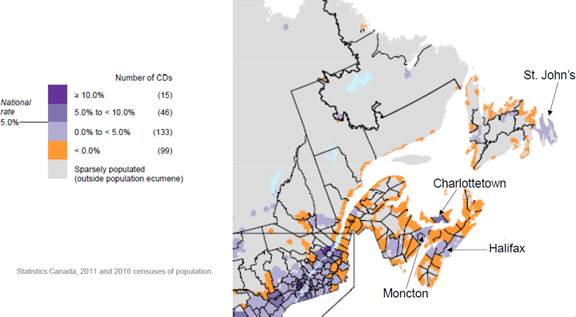

Source: Table complied by the authors using Statistics Canada, “Immigration and Ethnocultural Diversity Highlight Tables,” 2016 Census, Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 98-402-X2016007, Ottawa, 2017. This relatively smaller share of immigration to the region is also observed when comparing the number of newcomers to Atlantic Canada to Canada’s overall numbers. Table 4 shows that from 2006 to 2015, the number of immigrants arriving through federal immigration programs as permanent residents to Atlantic Canada slowly increases each year. Table 4 – Permanent Residents Admitted to Atlantic Canada by Province from 2006 to 2015

Source: Table complied by the authors using Government of Canada, “Canada - Permanent residents by province or territory and urban area”, Facts & Figures 2015: Immigration Overview - Permanent Residents – Annual IRCC Updates. According to the Atlantic Provinces Economic Council, the number of immigrants to the Atlantic region has increased mainly due to the “growth in numbers entering through the Provincial Nominee Programs”[37] of each Atlantic province, “whereby the provinces select and nominate potential immigrants who … are approved by the federal government for permanent residency.”[38] For instance, in 2015, Atlantic Canada received 4,640 individuals through the Provincial Nominee Program[39] and 2,533 people through federal immigration programs.[40] In 2015, the region also received about 1,110 refugees and other immigrants admitted on a humanitarian basis.[41] Mr. Wadih Fares, President and Chief Executive Officer of W.M. Fares Group, outlined the strength of Nova Scotia’s Provincial Nominee Program by highlighting that 2016 was a record year for immigration, with nearly 5,500 new immigrants.[42] He also noted that “Nova Scotia welcomed over 1,500 Syrian refugees through government-assisted, private, and blended sponsorships. This is a significant increase compared with previous years in which our province typically resettled only about 200 refugees.”[43] Recent census data shows that in 2016 “[e]ach of the Atlantic provinces received its largest number of new immigrants, which more than doubled the share of recent immigrants in this region in 15 years.”[44] Nevertheless, in 2016, Atlantic Canada had an overall share of national immigration of 4.6%,[45] whereas the share for Quebec was 18%, Ontario was 37% and Western Canada was 40%.[46] Witnesses emphasized that Atlantic Canada is not getting its “fair share”[47] of immigration and without a larger base it “can't get the critical mass to attract more immigrants.”[48] When retention rates of immigrants to Atlantic Canada (and perhaps any rural area of Canada) are factored in, the net benefit to Atlantic Canada is much less than the benefit enjoyed by the country as a whole, especially in urban areas. To be equitable and to address the current crisis, the immigration target for Atlantic Canada should take retention into account. Consequently, the Committee recommends: Recommendation 1 In light of the challenges in retention, that Immigration Refugees and Citizenship Canada work in collaboration with provincial governments to increase the share of newcomers to the Atlantic Provinces and to adequately fund the infrastructure needs and support services for the immigrant community in Atlantic Canada. Recommendation 2 That Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada work with the Atlantic Provinces to ensure adequate provision of settlement services to attract and retain newcomers to these areas. 3. Regional disparities between rural areas and urban centresThe demographic challenges within the regions and provinces of Atlantic Canada are not all the same. Some regions in Atlantic Canada have relatively high population growth, mainly in urban centres such as Halifax (N.S), Moncton (N.B.), St. John’s (N.L.) or Charlottetown (P.E.I.).[49] For example, between 2006 and 2016, Fredericton (N.B.) grew by 14.9%, Charlottetown by 12.5%, and Halifax by 8.3%.[50] However, Atlantic Canada still has a relatively higher proportion of its population in rural areas than the rest of Canada. Professor James Ted McDonald from University of New Brunswick pointed out that 48% of New Brunswick’s population lives in rural areas, compared to 19% for Canada overall.[51] To provide a better understanding of this regional disparity, he said that the “last time Ontario and Quebec were 48% rural was in 1921. Even Saskatchewan, with 33% of its population in rural areas, last had a 48% rural population in 1976.”[52] Nevertheless, the Committee saw that the regions with declining populations are essentially in rural Atlantic Canada, as seen in Figure 1.[53] These decreases in most rural areas are due to outward migration to urban areas either in Atlantic Canada or elsewhere in the country.[54] Figure 1 – Population Growth in Atlantic Canada by Census Divisions (CDs) from 2011 to 2016

Source: Graphic submitted to the Committee by Laurent Martel, Atlantic Canada: Key Demographic Challenges. Mr. Finn Poschmann, President and Chief Executive Officer of the Atlantic Provinces Economic Council, observed that, among Canada's provinces, Atlantic Canada has the highest unemployment rates, which are above 8%, and the lowest employment to population ratios overall.[55] However, others argued that cities in the Atlantic Provinces are doing well, with low unemployment rates.[56] As an example, Mr. MacDonald indicated that, “in May 2017, the unemployment rate in the Moncton, New Brunswick, census metropolitan area or CMA was 6.1%, and in Saint John 5.6%, compared with 6.7% in Peterborough and 5.6% in Abbotsford.”[57] Urban centres in the Atlantic region are also relatively successful in attracting immigrants compared to rural areas; in New Brunswick, 80% of immigrants are choosing to reside in the main three cities.[58] On the other hand, rural areas in Atlantic Canada face high unemployment rates, which, according to Mr. McDonald, “arise from an older, less skilled workforce who have lost jobs in forestry and fisheries and whose skills are not readily transferred.”[59] For example, the unemployment rate is “11.8% in P.E.I. and 12.3% in New Brunswick. By way of contrast, the unemployment rate of rural Quebec is 5.4% as of May 2017.”[60] Witnesses remarked that immigration is difficult for recent immigrants in rural areas in Atlantic Canada[61] because there is a lack of social infrastructure, such as high-quality and high-speed internet and public transit.[62] As one witness concluded, “[t]he Atlantic Provinces are urbanizing, and immigration on its own will not solve the challenges of rural areas and small towns in these provinces.”[63] 4. Labour shortages in a variety of sectorsThe Committee also heard that labour shortages in the sectors of agriculture, construction, fisheries, hospitality, and transportation in Atlantic Canada are higher than the national average.[64] According to Mr. Reint-Jan Dykstra, Director at the Canadian Federation of Agriculture, the agri-food sector is constrained by chronic labour shortages, despite increasing wages and decreasing unemployment in the sector.[65] He clarified that this is a national issue with 59,000 vacancies across Canadian agriculture, with a job vacancy rate of 7%.[66] He warned that the vacancy rate will double by 2025 due to population aging.[67] According to a 2015 study conducted by the Canadian Agriculture Human Resource Council cited by Mr. Dykstra, these vacancies result in $1.5 billion in lost potential sales each year.[68] Mr. Adam Mugridge from Louisbourg Seafoods Ltd. echoed Mr. Dykstra’s comments in relation to labour shortages due to an aging labour force. Indeed, the average age in Louisbourg Seafoods Ltd processing plants in Nova Scotia is 58 years old.[69] In Atlantic Canada, the rate of private sector job vacancies is around 3% in construction and hospitality, whereas the national rate is about 2.4%.[70] Ms. Juanita Ford from Hospitality Newfoundland and Labrador also shared her projections: the tourism sector in Newfoundland and Labrador could reach a 15.2% job vacancy rate by 2035, leaving over 3,000 jobs unfilled.[71] This would result in a “shortfall in revenue to the tourism sector in Canada by 2035 [that is] estimated at $27.5 billion,”[72] which will “hamper growth, decrease investment in the sector, cause higher operating costs, reduce profits, erode the sector's ability to compete, and cause inferior customer service.”[73] Other witnesses stated that, in their industry, they need to fill some positions with immigrants in order to grow their company. Mr. Vaughn Hatcher from Day and Ross Transportation Group stated that he needed more people in his company to drive an extra 2,000 loads a year to the United States from Atlantic Canada.[74] Digital Nova Scotia projected a 3.5% growth in the information communications technology industry between 2017 and 2021, but the sector reported difficulty finding workers.[75] The financial sector in Nova Scotia described the same difficulty.[76] The province estimated that by 2021 there will be a need for “55,000 new workers due to a shrinking labour pool.”[77] These labour shortages are caused by a retiring workforce and a difficulty in finding workers with the appropriate skills in the geographic region. According to Mr. Akbari, the population decline affecting mostly rural Atlantic Canada is of concern because most natural resource based industries in the region are located in rural areas.[78] In addition, Mr. Jordi Morgan from the Canadian Federation of Independent Business indicated that the shortage of qualified labour is a top priority issue for small and medium enterprises because it limits them from growing their business.[79] In a brief submitted to the Committee, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) suggested that labour shortage predictions could be factored into Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada’s immigration point system in order to address the shortage of qualified labour and incentivize industries in hiring immigrants.[80] As such, the Committee recommends: Recommendation 3 That the Government of Canada, in collaboration with Atlantic Provinces and stakeholders, consider predicted labour shortages in all skill levels when planning and delivering their immigration related policies and programs. Recommendation 4 That Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, in collaboration with the Atlantic Provinces, improve programs tailored to address francophone immigrant recruitment, including outreach campaigns specifically aimed toward countries with French as an official language; to develop strategies for integration and retention needs specific to the different contexts of francophone minority communities; to revise the applicant requirements for provinces so that the percentage of francophone or francophile applicants selected is targeted to the percentage of francophones in each provinces; and to develop an evaluation and accountability framework to measure progress achieved and ensure attainment of immigration objectives in these communities. Recommendation 5 That Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada better ensure that funding is made available to settlement services and language training in French in the region to improve the sustainability of the region’s French communities. 5. Impact on the tax baseWitnesses warned the Committee that an aging and declining population results in fewer labour force participants, thereby leading to shrinking markets for goods and services which have an adverse impact on incentives for business investments and tax revenues.[81] One particularly striking example was provided by Ms. Amanda McDougall, a municipal councillor for the Cape Breton Regional Municipality in Nova Scotia. She explained how the declining population challenge faced by her municipality influences the municipality’s revenue streams. She emphasized that 1,500 people leave Cape Breton Island each year,[82] which means a $19 million loss in consumer spending,[83] not to mention taxable income. According to her, this demographic challenge will only increase in the coming years because, out of the 2,005 immigrants that chose Nova Scotia in 2015, only 92 people settled in Cape Breton Island.[84] She was also concerned that other rural regions in Nova Scotia welcomed among them a shared number of 10 people that same year.[85] For her, immigration is essential to get “more people in the area to contribute to [the] tax bases”[86] because immigration is connected to economic development. 6. Impact on social servicesDuring the study, witnesses acknowledged another set of challenges: the impact of an aging and declining population on the social services provided by provincial and municipal governments. As summarized by Mr. Frank McKenna, Deputy Chair of the TD Bank Group, and former Premier of New Brunswick, Aging populations cost more, the declining population base results in less equalization, fewer transfers for health and education, less money from income tax, less money raised from consumption tax, and then we have to care for an aging population, which is exponentially more expensive. The results are starkly visible: universities are struggling for students, our high schools are sometimes half full and, of course, everybody is fighting to keep their school full and we have bed-blockers in all our hospitals.[87] Member of Parliament Alaina Lockhart testified as sponsor of the private member’s motion that her constituents in Fundy Royal, New Brunswick, are “concerned about their rural schools, the corner stores in their communities closing because of a lack of volume, and the dwindling memberships in organizations.”[88] In fact, Ms. Heather Coulombe, owner of Farmer’s Daughter Country Market, from Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia confirmed that there are schools and businesses that closed near her, mostly in rural areas.[89] Communities in Atlantic Canada, like those in other regions of the country, are beginning to understand the magnitude and impact of these challenges that will lead to the consolidation[90] or the loss of schools[91] and other difficulties regarding infrastructure such as hospitals, mail and banking services.[92] Mr. Akbari also informed the Committee that the cost of public and private services does not adjust immediately when the population declines and that there is a point below which base costs cannot go regardless of population size.[93] Population decline also means a corresponding decline of some federal funds determined by population size such as social and health care transfers.[94] A vicious circle can be created because an aging population puts pressure on younger labour force participants to provide for the social programs for the elderly, but higher contribution to Canadian Pension Plan and high taxes combined with the closure of public and private services can further accelerate outmigration and rural population decline.[95] Mr. Marco Navarro-Génie, President and Chief Executive Officer of the Atlantic Institute for Market Studies, reminded the Committee that “theatres, parks, schools, hospitals and festivals”[96] are important to Atlantic Canadians, but that funds are required to sustain and maintain these services.[97] As a result of these regional differences and demographic challenges, Atlantic Canada’s needs in terms of public services, social programs and infrastructure will vary more and more across the different regions of the four provinces. B. Public and private initiatives for immigrationThe Committee heard from a number of provincial officials and witnesses that have turned towards immigration to foster population and economic growth. Government officials recognize that immigration is important in supporting economic growth, while other witnesses spoke of employing foreign nationals and newcomers to Canada in order to grow their business and attract investments. 1. Provincial government initiativesOver the years, each Atlantic province has developed specific initiatives to grow its immigration. Since 2014, New Brunswick, as an official bilingual province, has had a strategy in place to attract Francophone immigrants,[98] as its immigration pattern does not currently reflect the demographic weight of both linguistic communities.[99] In 2017, the Government of New Brunswick hosted the first Forum sur l'immigration francophone to encourage francophone immigration outside Quebec[100] and its second Economic Opportunities Summit, which provided an opportunity for governmental and community organizations to share perspectives on immigration and population growth.[101] The University of New Brunswick has also created an Economic Immigration Lab to work with employers to help create more effective channels for hiring skilled immigrants.[102] The Nova Scotia Office of Immigration tabled its first annual report in 2015.[103] That same year, the province had expanded pathways available to immigration to Nova Scotia by targeting individuals with specific work experience or entrepreneurial skills under the Provincial Nominee Program.[104] In addition, it doubled its Provincial Nominee Program allocation from 600 nominees in 2013 to 1,350 in 2017 and it streamlined its immigration processing and service delivery.[105] The province has also increased its resources to focus on employer engagement to help them recruit skilled workers to Nova Scotia. The Nova Scotia Health Authority has also collaborated with Nova Scotia Immigration staff to recruit medical professionals at job fairs abroad.[106] The Government of Newfoundland and Labrador’s Immigration Action Plan, launched March 2017, lays out its priorities for the period 2017–2022. Key actions under the plan include improving immigration processing, supporting third party immigration organizations, the creation of a new website and web portal for immigrant applications, and education and training for employers.[107] In August 2017, the government of Newfoundland and Labrador issued a call for proposals to enhance immigrant settlement and recruitment. It has indicated that priority will be given to expanding or supporting English-as-a-Second-Language services.[108] In May 2017, the Government of Prince Edward Island announced “a new population action plan for P.E.I., focusing on recruitment, retention, repatriation, and rural economic development.”[109] The province also issued a request for proposals for "immigration agents" who will work to attract immigrants, particularly entrepreneurs, to live and work on the island. The agents’ main focus will be to make immigrants aware of economic opportunities in rural areas and to encourage them to purchase or invest in existing P.E.I. businesses.[110] In August 2017, the government of P.E.I. announced the creation of four Regional Economic Advisory Councils, tasked with providing recommendations to Cabinet on economic growth. Among other priorities, the councils are designed to “enhance population growth in each region, and specifically help in targeted population attraction drawn by employment and economic opportunities.”[111] 2. Private sector employing foreign nationalsAs stated previously, there are high labour shortages in multiple sectors in Atlantic Canada and a number of witnesses spoke about employing newcomers in order to meet the labour demand in their sector to fill gaps.[112] As Ms. Juanita Ford of Hospitality Newfoundland told the Committee, the tourism sector has relied heavily on young people as a source of labour. However, the rate at which young people are entering the labour force is decreasing while competition to attract younger workers is intensifying from other sectors of the economy. The industry will experience a shortage of people, in general, to fill positions, and a much more pronounced deficiency in skilled workers to fill positions.[113] She also noted that the hospitality industry, like others, has focused on integrating non-traditional labour pools, such as youth, Indigenous persons, and people with disabilities, into the workforce. However, these initiatives are not enough and immigration is needed to fill the labour demand. Indeed, almost a quarter of the 18,000 tourism workers in Newfoundland and Labrador are immigrants, including 40% of all chefs,[114] however retention remains a problem. Mr. Bill Allen, Chairman of the Board of Restaurants Canada, owns six restaurants in P.E.I., Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. He told the Committee that for the last ten years he has hired “over 50 temporary foreign workers who have made their way through into the provincial nomination program, and then through to, in many cases, their PR [permanent residence].”[115] Other industries, such as agriculture or fisheries also depend heavily on foreign nationals.[116] For example, the Canadian Federation of Agriculture stated that farmers turn to foreign workers for both seasonal and full time positions because of limited access to labour and experienced workers.[117] Nationally, the agriculture industry brings in approximately 45,000 foreign nationals each year, which represent 12% of the industry’s workforce.[118] Mr. Mugridge also explained to the Committee how his company Louisbourg Seafoods Ltd. depends on foreign workers for a third of the workforce, which has 500 employees during its busiest periods.[119] In this region, there is a high rate of unemployment, but also a labour shortage of persons with the required skills. In P.E.I., Mr. Craig Mackie, from the Prince Edward Island Association for Newcomers to Canada, noted that immigrants are working in almost all sectors of the economy, including the new areas of bioscience and aerospace, which require highly-skilled workers.[120] 3. Need for capital investmentsProfessor Herb Emery, Vaughan Chair in Regional Economics at the University of New Brunswick, drew the Committee’s attention to the need for private sector investment to increase labour demand and create opportunities for newcomers.[121] He warned that economic growth is not just a question of adding more labour supply to the market. According to him, economic growth also requires investments, wage growth stimulation and higher labour productivity that will spur more interest in the market.[122] He provided Saskatchewan as an example that reversed their population-aging trend and attracted immigrants through new investments in its resource projects and industries.[123] In his opinion, Professor Emery described the labour market as dysfunctional where wages and employment do not adjust adequately.[124] He stated that adding more people into a dysfunctional labour market might not resolve the problem, which potentially influences the outcome of immigration programs such as the Atlantic Immigration Pilot Program.[125] Mr. Jeffrey Green, Director, Talent Acquisition, J.D. Irving Ltd., echoed the comments of Professor Emery and stated that capital investment is an important factor when forecasting labour and skills shortages. As an example, a quarter of J.D. Irving Ltd.’s forecast is influenced by growth, such as capital investments.[126] The Committee has identified that there are challenges in each stage of the immigration lifecycle, namely recruitment, processing, settlement and retention, and there are recommendations to be made to address perceived deficiencies. As such, the Committee recommends: Recommendation 6 That Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada take into consideration the other pillars of the Atlantic Growth Strategy, namely innovation, infrastructure, clean growth and climate change, and trade and investments, when implementing immigration policy under the Atlantic Growth Strategy in order to more effectively respond to labour demand in Atlantic Canada. Recommendation 7 That Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada take the immigration lifecycle of recruitment, processing, settlement and retention, into consideration when implementing immigration policy and programs under the Atlantic Growth Strategy. Part 2: Bringing Immigrants to Atlantic CanadaPart 2 provides a brief overview of the current programs and policies that attempt to bring newcomers and foreign nationals to Atlantic Canada. Witnesses identified a number of challenges to immigration with the programs and services as currently delivered. Some are within the department’s processes, others are policy choices of IRCC and provincial governments. The four Atlantic Provinces are making a concerted effort to work together to confront the region’s demographic and labour market challenges. Collaborative initiatives in the field of immigration have included advocating for additional provincial nominee places and recruiting international students. The Atlantic Growth Strategy, which includes the Atlantic Immigration Pilot program, is the latest initiative developed in collaboration with the federal government. A. Atlantic Growth StrategyThe Atlantic Growth Strategy is a multi-pronged strategy to address long standing concerns regarding economic growth in the region, which has not kept pace with the national average. The first pillar of the Atlantic Growth Strategy focuses on immigration and a skilled work force, where the other pillars of growth are innovation, infrastructure, clean growth and climate change, and trade and investments.[127] The first initiative of the Strategy is the Atlantic Immigration Pilot Program. The Atlantic Growth Strategy is led by a Leadership Committee comprised of the Premiers of the four Atlantic Provinces and members of the federal cabinet.[128] The Leadership Committee receives advice from the Atlantic Growth Advisory Group,[129] chaired by Mr. Henry Demone from High Liner Foods Inc., Nova Scotia. The Advisory Group was struck “to engage with Indigenous, business, academic, community and civil society leaders on ways to enhance regional growth.”[130] 1. Atlantic Immigration Pilot ProgramAs of March 2017, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) started accepting permanent resident applications through the Atlantic Immigration Pilot Program,[131] which is a three-year immigration project which includes a specific stream for international graduates. Officials from IRCC presented the Atlantic Immigration Pilot Program (AIPP) to the Committee. Ms. Laurie Hunter, Director of Economic Immigration Policy and Programs at IRCC, explained that the AIPP provides priority processing for permanent residence applications in the intermediate-skilled, high-skilled and international graduate programs.[132] Unlike some other programs, employers are not required to obtain a Labour Market Impact Assessment (LMIA) for jobs offered in the context of this pilot project. However, a unique aspect of the pilot project is the requirement for employers to provide an individualized settlement plan to support each of the newcomers’ integration into the community. The goal for 2017 was to process 2,000 applications (principal applicants and family members) through the pilot project.[133] By way of example, a quota of 646 families was allocated to New Brunswick under the AIPP for the first year.[134] The provincial government allocated additional funding to assist settlement services and to reach out to employers, hoping to raise the province’s immigrant retention rate[135] of 72% to 80%.[136] Outreach to individual businesses has led to significant interest and participation in the program. Jobs have been identified in various sectors including IT, business service centres, contact centres, transportation, aquaculture, seafood processing, agriculture, forestry, food manufacturing, manufacturing, home care, hospitality and food services, administration, and finance.[137] Mr. Charles Ayles, a senior official from the Government of New Brunswick, stated that teams overseas are having success in recruiting qualified immigrants.[138] Prince Edward Island has a quota of 120 families under the AIPP, although these may be redistributed amongst the other provinces in the region if that target is not met. Deputy Minister Neil Stewart testified that P.E.I. was cautious about requesting higher levels of immigrants through the pilot program, stating “[w]e want to see our retention rates before we seek higher levels”.[139] Mr. Morgan from the Canadian Federation of Independent Business saw a number of positive elements in the AIPP; such as the elimination of the LMIA, the improved speed of processing and the inclusion of intermediate skilled jobs, while most federal programs for permanent residence target high skilled workers. He was cautious about the capacity of small and medium-sized businesses to develop and deliver individualised settlement plans.[140] Ms. Gerry Mills, Executive Director, Immigrant Services Association of Nova Scotia, informed the Committee that her organization had developed 123 settlement plans to date, assisting employers across the four provinces, especially small and medium-sized businesses that did not have the expertise nor the resources to respond to the settlement plan needs of their employees.[141] While the program is in its first year, a number of witnesses have already experienced difficulties with the AIPP. Ms. Angelique Reddy-Kalala of the City of Moncton told the Committee that having settlement plans by designated organizations, of which none were located in New Brunswick, was problematic.[142] For Mr. Allen, of Restaurant Canada, the entire process was difficult. After eight months, they were ready to submit a potential employee’s application for review that consisted of a 55 page document.[143] He qualified the processing as proceeding “at a snail’s pace”[144] and inefficient because “there are 15 steps before you can make the application.”[145] He also expressed frustration with the lack of information and knowledge that he received when asking the same question to IRCC offices, claiming to have received three different answers on three different days.[146] For those reasons, Mr. Luc Erjavec, of Restaurants Canada, suggested a digitized process through an online portal.[147] Mr. Dave Tisdale hired a long-haul trucker through the AIPP, but he said it had been a complicated process even though the foreign national was already in Canada.[148] Furthermore, few students are aware of their eligibly for the specific stream designed for international graduates.[149] Some committee members were taken aback to hear how difficult the AIPP process was and the delays involved for some employers, as expedited processing had been one of the priorities underlined by IRCC officials. The Committee was concerned to hear conflicting evidence on the complexity of the process for employers in different Atlantic Provinces. Some members of the committee question whether the complexity of the AIPP arose out of IRCC or provincial complications. The Committee recommends: Recommendation 8 That Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, with the Atlantic Provinces, annually evaluate the Atlantic Immigration Pilot Program; ensure that the process is harmonized, simplified and expedited for Atlantic Canadian business applicants; and provide the Committee with details of the new process. Recommendation 9 That Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada digitize the application process for the Atlantic Immigration Pilot Program. B. Provincial Nominee ProgramEach province in Atlantic Canada has negotiated an agreement with the federal government for a Provincial Nominee Program (PNP).[150] The PNP allows provincial governments to develop their own economic immigration streams in order to meet regional priorities. The New Brunswick Minister of Post-Secondary Education, Training and Labour, the Hon. Donald Arseneault, stated that historically, the NBPNP has been used to retain skilled and business immigrants.[151] It now has a stream incorporated into Express Entry, a system which will be further detailed below.[152] In 2016, New Brunswick exceeded its objective in welcoming francophone immigrants through the PNP.[153] The Prince Edward Island Minister of Workforce and Advanced Learning, the Hon. Sonny Gallant, confirmed that immigrants settled in P.E.I. mainly through the PNP.[154] The P.E.I. PNP includes streams for businesses as well as for entrepreneurs.[155] The Newfoundland and Labrador Provincial Nominee Program has a stream for skilled workers, a stream for skilled workers in Express Entry and a stream for international graduates.[156] The Nova Scotia Nominee Program has three streams targeting entrepreneurs, international graduate entrepreneurs and skilled workers and two streams incorporated into Express Entry, one for high skilled individuals (Nova Scotia Demand: Express Entry) and one for those who already have one year of experience working in Nova Scotia (Nova Scotia Experience: Express Entry).[157] The federal government assigns each participating province a certain limit of PNP applications for a given year. Table 5 below shows how many permanent residents were admitted to each Atlantic province from the years 2010 to 2015. According to the Atlantic Provinces Economic Council, the region was assigned 2,325 principal applicant nominees for 2016, including family members.[158] Table 5 – Permanent Residents Admitted through the Provincial Nominee Program

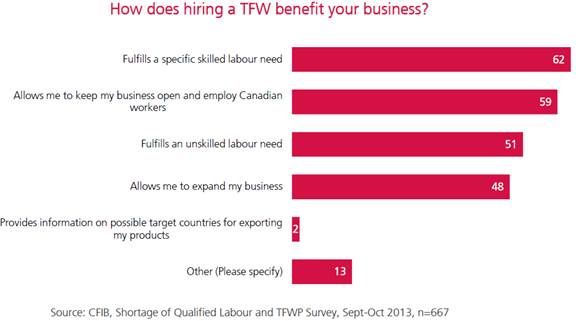

Source: Table complied by the authors using the annual reports to Parliament on immigration published by Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada from 2011–2016. Ms. Gerry Mills of the Immigrant Services Association of Nova Scotia, told the Committee that “[m]ost of our immigrants to Nova Scotia come through the PNP stream. If the federal government is truly interested in increasing immigration to the Atlantic, raise or eliminate the caps.”[159] Some witnesses stated that there appears to be reluctance on the part of some provinces or businesses to move from the Provincial Nominee Program (in which government evaluates labour market needs without a settlement plan) to the Atlantic Immigration Pilot Program (with specific settlement obligations and a designation requirement without a government assessment of labour market needs). Moreover, some witnesses also noted that the Atlantic Immigration Pilot Program, as proposed by the Minister, takes the Labour Market Impact Assessment out of the hands of the government and puts it into the hands of designated industry employers who can more efficiently know the labour market demands. As such, the Committee is hesitant to recommend changes to the Provincial Nominee Program before the Pilot Program has been properly assessed. C. Express Entry for high-skilled immigrationSince January 2015, IRCC’s Express Entry[160] is a two-step application management system for key economic immigration programs. Individuals create an online profile that puts them in a pool where they are ranked using the Comprehensive Ranking System (CRS). Through ministerial instructions issued regularly, top ranking candidates’ expressions of interest are pulled from the pool and they are invited to complete an immigration application. The economic immigration programs covered by Express Entry include the Canadian Experience Class, the Federal Skilled Worker Program, the Federal Skilled Trades Program and a portion of the Provincial Nominee Program. Ms. Laurie Hunter described recent changes to Express Entry that in her opinion would have a positive impact on the Atlantic region. For example, more points are now awarded to post-secondary graduates from Canadian institutions and more points to candidates with strong French language skills. High-skilled workers whose application is exempt from Labour Market Impact Assessment (LMIA) no longer require their job offer to be supported by an LMIA to receive additional points in Express Entry.[161] 1. Objective: faster processingExpress Entry is the program that currently offers the fastest processing time from the date the applicant submits a complete application and receives her or his permanent resident visa: IRCC’s service standards indicate this is done in six months or less (80% of the cases).[162] As stated in the UNHCR-OECD summary of the Business Dialogue held in Toronto, six months “is a long time for a company to wait when they have an immediate labour need.”[163] The Atlantic Provinces Economic Council indicated in a written submission that [L]engthy processing times are a barrier to greater use of immigration by the business community.... The federal government needs to ensure it has sufficient resources to process all economic applications in a timely manner, including the new Atlantic Immigration Pilot and all provincial nominees.[164] In this context, Mr. Fares recognized that to process all applications in a timely manner the federal government had to have sufficient resources.[165] Taking these comments into consideration, the Committee recommends: Recommendation 10 That Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada model the service level standards, including processing times, for the Atlantic Immigration Pilot Program on those currently existing for Express Entry, for which expected processing times now stand at less than six months. D. International studentsInternational students make up 20% of full-time enrolment in universities in the Atlantic region.[166] In 2009-2010, they contributed $565 million to the economy across the region.[167] In 2016, a survey conducted amongst the university and college graduates in the region indicated that 75% of respondents intended to remain in the region. A 2017 follow-up survey[168] showed that 64% had remained, and 26% indicated that they had left because of the lack of employment opportunities in their field of study. The Government of Newfoundland and Labrador has identified international students as a source of potential immigrants and has a designated staff person at the Office of Immigration and Multiculturalism to assist students with labour market and immigration advice.[169] The province also plans to partner with employers to create internships for international students as well as to pilot a program called “My First Newfoundland and Labrador Job”.[170] Students who wish to work after graduation in Canada can obtain a Post-Graduate Work Permit (PGWP),[171] however its length is dependent on the number of years of study. The current trend of one year masters degrees means that PGWPs valid for one year are common. Ms. Sofia Descalzi, Chairperson, Canadian Federation of Students-Newfoundland and Labrador, shared her experience of being an international student with the Committee.[172] A recruiter from Memorial University visited her high school in Ecuador and she eventually received a scholarship for one year’s tuition. She then experienced difficulty finding part-time work off campus, discovering that employers were reluctant to hire a foreign national. She said that not having constant health-care coverage (as it is tied to full-time study) had also given her much concern. She informed the Committee that international students were frequent users of campus food banks.[173] She suggested that, in order for international students to remain in Canada, they need better pathways to citizenship and job opportunities. Ms. McDougall also stated that the lack of front-line immigration services was a major deterrent in keeping international students on Cape Breton Island.[174] The Committee understands that international students have been identified as potential immigrants to Atlantic Canada. For international students to transition to permanent residents, they need more support. Recommendation 11 That Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, allow international students in the Atlantic Immigration Pilot Program and those who have been recruited by a designated employer under the Atlantic Immigration Pilot Program to access settlement services once they have started the permanent residency application process. 1. Flexibility for international students to remain and work in Atlantic CanadaProfessor Natasha Clark of Memorial University testified that, in her experience, it was difficult for international students to become permanent residents with Express Entry, as their scores were not high enough to be competitive. She explained that “even with new changes to the comprehensive ranking system, an international graduate with a bachelor's degree and one year of work experience in Canada does not necessarily score highly enough to be competitive in the Express Entry pool.”[175] She informed the Committee that international students lack labour market opportunities and face “challenges to entering the labour market”.[176] Ms. Penny Walsh McGuire, of the Greater Charlottetown Area Chamber of Commerce, also spoke of the need to give international students work experience before they graduate, and yet international students were not eligible for the Canada Summer Jobs Program, and co-op study permits were difficult to obtain in a timely fashion.[177] She suggested that post graduate work permits be valid for five years regardless of the program of study.[178] The Committee heard that an international student accepted in a co-op program would have difficulties, not in finding placement, but in the strict application of issuance of work permits. Further, seeing that Post Graduate Work Program are the key to permanent residence through Express Entry (Canadian Experience Class) it seems that in Atlantic Canada it would be useful to guarantee a length to this type of work permit. The Committee observed that in order for recent graduates to have a reasonable opportunity to succeed in the Canadian workforce, they must first gain valuable Canadian work experience so that employers are more likely to recruit them and assist them in securing permanent residency under an existing program or the Atlantic Immigration Pilot Program. The Committee recommends: Recommendation 12 That Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, work with relevant stakeholders to issue work permits to students that are valid throughout their study program in Atlantic Canada, including co-op terms, and issue post graduate work permits valid for five years in Atlantic Canada. E. Temporary foreign workers and Labour Market Impact AssessmentTemporary foreign workers (TFWs) are hired for periods not exceeding eight months, on the basis that no qualified permanent resident or Canadian is available to do the work. This involves job postings and obtaining for a fee a Labour Market Impact Assessment from Employment and Social Development Canada.[179] A closed work permit is then issued after the worker’s application is reviewed abroad. In 2014, caps were introduced to limit the number of temporary foreign workers an employer could hire.[180] Eventually, an exemption was provided to seasonal industries waiving the cap on TFWs in place until the end of 2017.[181] A report by the Atlantic Provinces Economic Council states that the use of TFWs tripled in the Atlantic region between 2005 and 2012, from 3,499 TFWs to 10,913 foreign nationals.[182] Despite this rapid growth, TFWs in 2012 represented only 1% of total employment in the Atlantic region, compared with 1.9% nationally. Temporary foreign workers primarily filled labour shortages in lower paying, lower skill occupations such as fish plant and food service workers. Mr. McKenna stated that the Temporary Foreign Worker Program was integral to the labour market, and informed the Committee that hundreds of jobs had been shifted out of the region following the reforms to the program in 2014.[183] He suggested that a pathway to permanent residency for TFWs should be established.[184] Mr. Mugridge spoke of the seasonal work in the fishery industry that employs, at its annual peak, 500 employees in coastal communities of Nova Scotia.[185] He explained that TFWs comprise a third of his workforce.[186] Mr. Mugridge said they were trying to develop new seafood products that would translate into full-time jobs for these workers.[187] Mr. Kevin Lacey, Director, Atlantic, Canadian Taxpayers Federation, told the Committee that TFWs are hired to respond to labour shortages although there are high unemployment rates in the region, a situation that keeps wages down.[188] Mr. Morgan explained that employers sought TFWs at great cost,[189] but access to the program had assisted them to expand their businesses and to continue to employ Canadian workers. He provided the Committee with a survey that showed the main reasons businesses used TFWs, as seen in Figure 2. Figure 2 – Small Businesses’ Top Reasons to Hire Temporary Foreign Workers