FINA Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

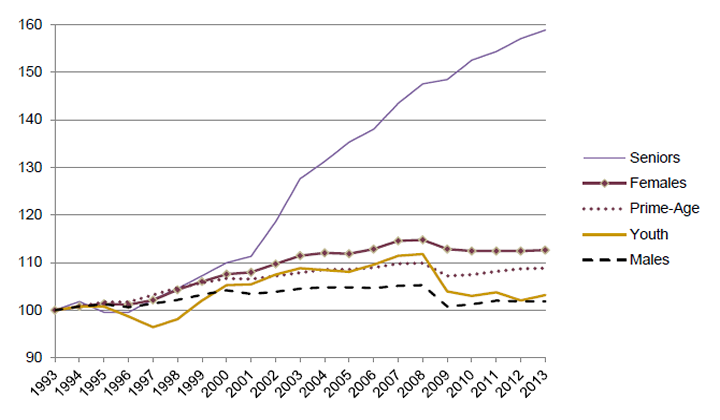

CHAPTER SEVEN: MAXIMIZING THE NUMBER AND TYPES OF JOBS FOR CANADIANSA. Background1. EmploymentIn 2013, 17.7 million people – about 15 million employees and approximately 2.7 million self-employed persons – were employed in Canada, an increase of 1.3% – or 223,500 people – from 2012. This increase continued the trend of rising employment levels in Canada that has existed since the end of the recent global recession. As shown in Figure 14, Canada’s employment rate – the number of people employed as a percentage of the number in the working-age population – has generally been rising over the last two decades, although the employment rate in 2013 – at 61.8% – was below its 2008 peak of 63.5%. By gender, almost all of the increase in the employment rate over the last 20 years has been due to more women becoming employed. Figure 14 – Employment Rate, by Gender and Age Group, Canada, 1993–2013 (Index: 1993=100)

Notes: “Employment Rate” is the number of people employed as a percentage of the population aged 15 and older. The rate is indexed to 100 for the year 1993. “Youth” are aged 15 to 24, “Prime-Age” are aged 25 to 54, and “Seniors” are aged 55 or older. Source: Figure prepared using information from: Statistics Canada, Table 282-0002, “Labour force survey estimates (LFS), by sex and detailed age group, annual,” CANSIM (database), accessed 10 November 2014. By age group, the number of senior workers – those aged 55 or older – nearly tripled over the last 20 years, rising from 1.2 million in 1993 to 3.4 million in 2013; their employment rate grew from 22.1% to 35.1%. Relative to senior workers, the employment rate for prime-age workers – those aged 25 to 54 – grew less, rising from 74.9% in 1993 to 81.5% in 2013, and that for youth – those aged 15 to 24 – was relatively unchanged over the period, at 53.4% in 1993 and 55.1% in 2013. Over the 2008–2013 period, the youth employment rate declined, falling from 59.7% in 2008 to 55.1% in 2013; the employment rate for prime-age workers remained at around 82.0% throughout the period, while the rate for senior workers grew from 32.6% to 35.1%. The 2 million employees involved in temporary work arrangements in 2013 – that is, in seasonal (21.3%), term or contract (53.4%), or casual or other jobs (25.2%) – accounted for about 13.4% of the 15 million employees in that year. While the number of permanent employees as a percentage of all employees decreased from 88.7% in 1997 to 86.6% in 2013, the number of temporary employees as a percentage of all employees increased from 11.3% to 13.4%; in the latter case, more than one half of the increase occurred after the onset of the recession in the fall of 2008. Direct federal funding to support employment is provided through the Youth Employment Strategy, which supports young people – especially those facing barriers to employment – as they transition to employment; the Strategy includes Skills Link, Career Focus, Canada Summer Jobs and the Federal Student Work Experience Program. Employment and Social Development Canada’s operating funds support various national employment services to help Canadians find suitable employment; these services include the Job Bank, Labour Market Information, and general job referral and placement services. The federal government also supports programs aimed at increasing the employment of people with a disability, including through the Opportunities Fund for Persons with Disabilities, the Enabling Accessibility Fund and the Entrepreneurs with Disabilities Program. Finally, federal personal tax measures that facilitate employment include the child care expense deduction, the Universal Child Care Benefit, the moving expense deduction and the Working Income Tax Benefit. Relevant tax measures for businesses include the Apprenticeship Job Creation Tax Credit, the Hiring Credit for Small Business and the Small Business Job Credit. 2. UnemploymentIn 2013, more than 1.3 million people in Canada were unemployed; this number was 20.8% lower than in 2008. Canada’s unemployment rate in 2013 – at 7.1% – was higher than the rate in 2008 – at 6.1%. In 2013, the unemployment rate for youth – at 13.7% – was higher than that for prime-age workers and senior workers – at 5.9% and 6.0% respectively. Over the 2008–2013 period, the 2.1-percentage-point growth in the youth unemployment rate was higher than that for prime-age workers and senior workers; their rates rose by 0.8 and 1.0 percentage points respectively. Figure 15 shows the unemployment rates – the number of unemployed people as a percentage of the number of people in the labour force – for youth, prime-age workers, senior workers, Aboriginal people, people with a disability and immigrants for selected years since 1996. Figure 15 – Unemployment Rate, by Population Identity, Canada, 1996, 2001, 2006 and 2011 (%)

Note: The unemployment rates by disability identity are available only for 2001 and 2006, and reflect people aged 15 to 64. Sources: Figure prepared using information from: Statistics Canada, 2001 Census of Canada, 2006 Census of Population, 2011 National Household Survey: Data Tables, Participation and Activity Limitation Survey, 2001: Education, employment and income of adults with and without disabilities – Tables, Catalogue No. 89-587-XIE, and Participation and Activity Limitation Survey of 2006: Labour Force Experience of People with Disabilities in Canada, Catalogue No. 89-628-X, No. 7. In Canada, the average duration of unemployment increased from 14.8 weeks in 2008 to 21.1 weeks in 2013. In 2013, 75.5% of unemployed people were unemployed for 26 weeks or less, while 33.1% were unemployed for 4 weeks or less; 20.2% were unemployed for 27 weeks or more, and 4.3% were unemployed for an unknown duration. The percentage of unemployed people who were unemployed for a year or longer more than doubled over the 2008–2013 period, rising from 74,800 people – or 6.7% of all unemployed people – in 2008 to 164,600 people – or 12.2% of all unemployed people – in 2013. The Employment Insurance (EI) program is funded by contributions made by employees, employers and self-employed persons. Through Part I of the EI program, the federal government uses EI funding to provide two types of income benefits for EI contributors who are temporarily unemployed and who meet certain requirements: Regular Benefits, which are provided in the event of job loss; and Special Benefits, which are provided in the event of illness, for the birth of a child and to care for a family member, among other situations. According to the EI Monitoring and Assessment Report 2012/13, 62.9% of EI contributors received Regular Benefits in 2012; this proportion is about the same as it was in 2003 – at 62.7% – but lower than it was in 2010 – at 71.7%. Table 2 presents various measures of EI eligibility and accessibility for the 2006–2007 to 2012–2013 period. Table 2 – Measures of Employment Insurance Eligibility and Accessibility

Notes: “EI Contributors” includes individuals who had paid EI premiums in the previous 12 months.

Source: Employment and Social Development Canada, Employment Insurance Monitoring and Assessment Report 2012/13, Chart 21, Chapter 2. Part II of the EI program supports EI beneficiaries’ transition to employment through skills training programs, employer incentives to hire workers, employee incentives to accept employment, guidance for starting a small business and assistance with job search. As specified in various Labour Market Development Agreements, these supports occur collaboratively between the federal and the provincial/territorial governments. As well, direct federal support occurs through Part II for pan-Canadian initiatives, such as the Aboriginal Skills and Employment Training Strategy (ASETS), which provides benefits to Aboriginal people who are EI beneficiaries and to other Aboriginal people, Research and Innovation, and Labour Market Partnerships with employers, employee and employer associations, community groups and communities. Canadians who are not eligible for EI are supported through federal transfer payments to the provincial/territorial governments for employment benefits and support measures. In particular, these measures occur through Labour Market Agreements for Persons with Disabilities and through Labour Market Agreements (LMAs); the introduction of the Canada Job Grant is occurring in the context of federal-provincial/territorial negotiations for the renewal of LMAs in 2014–2015. As well, the federal government is currently consulting with stakeholders on the future of Employment and Social Development Canada’s ASETS and the Skills and Partnership Fund. B. Changes Proposed by Witnesses Invited to Address “Maximizing the Number and Types of Jobs for Canadians”In speaking to the Committee about maximizing the number and types of jobs for Canadians, witnesses commented on a range of issues, including labour market information, labour mobility and temporary foreign workers, payroll taxes, Labour Market Development Agreements, training and skills development, entrepreneurship and sector-specific initiatives. 1. Labour Market InformationIn its brief, the Canadian Chamber of Commerce proposed that the Forum of Labour Market Ministers coordinate the collection and dissemination of labour market information to enhance the identification of skills shortages in Canada. As well, the Retail Council of Canada, the Canadian Federation of Independent Business and the Toronto Region Board of Trade’s brief supported improved labour market information to enable a clearer understanding of skills gaps and better labour market planning. The Canadian Labour Congress called for a national summit on the issue of improving labour market information. The Canadian Chamber of Commerce’s brief also requested that Statistics Canada expand its Job Vacancy Survey to identify skills gaps at a disaggregated geographical level. The Canadian Chamber of Commerce and the Canadian Labour Congress proposed that Statistics Canada reintroduce and expand its Workplace and Employee Survey. 2. Labour Mobility and Temporary Foreign WorkersTo reduce the need for temporary foreign workers, the Canadian Chamber of Commerce’s brief suggested that the government introduce incentives to defray the relocation costs incurred by skilled trades workers who are willing to work temporarily in rural or remote communities. In commenting on the need to address labour supply and allocation challenges, and to reduce the demand for temporary foreign workers, Canada’s Building Trades Unions proposed that the government offer either a labour mobility tax credit or a travel grant through the Employment Insurance program that would cover travel expenses incurred by workers for employment purposes; the credit or grant could be introduced immediately or following a pilot project. The Canadian Labour Congress’ brief called for the creation of a temporary migrant worker commission as an independent regulatory body that would monitor and enforce the transition to the elimination of all temporary work permits for low-skilled, low-wage jobs. The Quebec Employers’ Council urged an examination of the impacts on employers of the June 2014 changes to federal support for temporary foreign workers. In particular, the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers suggested that the government reintroduce the Canada–Alberta occupation-specific pilot project that allowed skilled temporary foreign workers to move between employers without prior federal authorization. Recognizing the need to access temporary help quickly in order to meet short-term production requirements, it requested that the government meet its service standard of a 10-day turnaround for labour market impact assessments in relation to temporary foreign workers. 3. Employment Insurance ContributionsThe Canadian Federation of Independent Business and the Canadian Chamber of Commerce proposed that employers and employees have the same Employment Insurance contribution rate. As a means of supporting on-the-job training, the Canadian Federation of Independent Business and the Quebec Employers’ Council advocated the creation of an employment insurance contributions credit for training expenses; employers that offer formal training to their employees would have a lower Employment Insurance contribution rate. The Quebec Employers’ Council’s brief also called for reintroduction of the 20% federal contribution to the EI program that existed until 1990, with the remaining 80% contribution shared equally between employers and employees. The Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers’ brief urged the creation of variable Employment Insurance contribution rates: rates for employers that reflect their record of layoffs; and rates for employers and employees that are positively correlated with regional unemployment rates, which could result in relocation to areas with lower rates of unemployment. 4. Labour Market Development AgreementsThe Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers’ brief suggested that the government reform the Labour Market Development Agreements – particularly the Targeted Wage Subsidy, the Self-Employment Program and the Job Creation Partnership – to ensure that services are delivered in a manner that is similar to provincial labour market agreements. To reduce job vacancies, the Canadian Federation of Independent Business supported employer access to Labour Market Development Agreement funding for a broader range of training options, including informal, on-the-job training. 5. Training and Skills DevelopmentIn focusing on ways in which to foster a training and skills development culture in Canadian workplaces, the Canadian Labour Congress, the Canadian Chamber of Commerce and the Metcalf Foundation proposed support for mentorship programs or other programs – such as paid internships and co-op initiatives – that would give workers on-the-job experience with small businesses. As well, to increase the number of apprentices who complete their training and become certified, the Canadian Chamber of Commerce’s brief advocated financial incentives for employers. The Metcalf Foundation also suggested that workplace skills development and productivity gains could be achieved by federal promotional campaigns to educate employers on the benefits of investments in workplace training. The Quebec Employers’ Council’s brief requested that the Apprenticeship Job Creation Tax Credit be extended to other apprenticeships managed by Quebec’s Commission des partenaires du marché du travail. To protect and enforce interns’ rights in the areas of compensation, health and safety standards, the Canadian Intern Association proposed that Parliament amend the Canada Labour Code to include – as employees – interns who work for federally regulated companies. To improve monitoring and reporting in relation to interns, it also urged Statistics Canada to include internships in its Labour Force Survey. Monster Canada suggested that the Department of National Defence, in partnership with employers, invest in a military skills translator to transition members of the Canadian Armed Forces to civilian jobs; these translators link a military member’s skills, experiences and training with appropriate civilian job opportunities. For this initiative, it proposed up-front funding of $1.7 million per translation unit, and annual operating funds of $400,000. 6. EntrepreneurshipStartup Canada requested funding of $15 million over three years to enable an increase, from 20 to 100, in the number of its Startup communities in urban and rural municipalities across Canada. Similarly, Futurpreneur Canada asked for funding of $37.5 million over five years to support 5,600 youth in its full start-up program – which offers loan financing and mentoring, business supports and networking for youth entrepreneurs for up to five years – and $2 million to help an additional 2,000 youth in its expanded stand-alone mentoring initiative. 7. Sector-specific InitiativesAs a means of creating scientific jobs, the Green Budget Coalition proposed a reinvestment in protecting Canada's environment through conservation. As well, to support green jobs, it advocated continuing progress on phasing out inefficient fossil fuel subsidies, no new subsidies for liquefied natural gas production, and an end to the Mineral Exploration Tax Credit. Moreover, with a view to meeting the Aichi Biodiversity Targets adopted by the United Nations in 2010, the Green Budget Coalition’s brief urged funding of $20 million annually for five years for jobs in conservation science. To support jobs in particular energy sectors, counter international trade cycles and limit the impact of changes in commodity values, the Institut de recherche et d'informations socio-économiques suggested that the government facilitate diversity in energy production beyond the oil and gas sector, especially in ecological transition and renewable energy. In focusing on rates in the United States and on jobs in Canada’s manufacturing sector, the Chemistry Industry Association of Canada urged the government to adopt a capital cost allowance rate of between 45% and 50% for machinery and equipment. The Toronto Region Board of Trade proposed that governments partner with industry to facilitate industry and academic co-ops and partnerships, and use community benefit agreements – which often identify requirements to train and hire local workers – in relation to major infrastructure projects. In noting that international markets create jobs, diversify revenue streams and increase tourism, the Canadian Arts Coalition advocated a $35 million increase in the 2015 parliamentary appropriation for the Canada Council for the Arts, with the long-term goal of $300 million annually. It also requested funding of $25 million over three years for cultural promotion in embassies, trade and business development, and international exhibitions by Canadian artists of their works. C. Changes Proposed by Witnesses Invited to Address Issues Other Than “Maximizing the Number and Types of Jobs for Canadians”The Committee’s witnesses were invited to speak about a particular topic. When they appeared, they often made comments about one of the other five topics selected by the Committee, as indicated below. 1. “Balancing the Federal Budget to Ensure Fiscal Sustainability and Economic Growth” WitnessesThe Canadian Taxpayers Federation called for a reduction in Employment Insurance contributions and transformation of the Employment Insurance program into individual employment insurance accounts; upon retirement, people could transfer the amount in their account to their savings. To support employment opportunities for veterans, the National Association of Federal Retirees proposed the creation of a tax credit for employers that hire veterans. In highlighting Germany’s virtual labour market system, the Canadian Council of Chief Executives advocated the establishment of a single, comprehensive portal that would centralize all data on labour market conditions and job vacancies. The Canadian Union of Public Employees, as a way to support job creation, called for increased public investments in infrastructure, affordable housing, renewable energy and energy efficiency, and the level of services that the government provides in these areas. To support growth in wage rates, it requested that the government cease its involvement in collective bargaining processes and introduce a federal minimum wage of $14 per hour. Moreover, it suggested that future federal budgetary surpluses be used to restore Employment Insurance benefits to their previous level, and that additional reforms be made to federal support for temporary foreign workers in order to protect domestic and foreign workers from abusive employers. 2. “Supporting Families and Helping Vulnerable Canadians by Focusing on Health, Education and Training” WitnessesYWCA Canada and the Childcare Resource and Research Unit proposed the creation of a national child care system that is similar to that in Quebec in order to increase Canada’s gross domestic product and net government revenues through higher female labour force participation. As well, the Childcare Resource and Research Unit urged the Department of Finance to evaluate the effectiveness of the following three measures, with the results of its evaluation made publicly available: the Universal Child Care Benefit; proposed plans for income splitting; and the child care expense deduction. Moreover, to strengthen provincial/territorial child care systems, it requested $700 million in emergency transfers to the provinces/territories. The Canadian Federation of Students suggested that Statistics Canada estimate the number of unpaid interns working in Canada, and that – as they are not covered by Canadian labour legislation – the government support the development of more direct mechanisms to monitor and enforce unpaid interns’ legal rights. The Canadian Federation of Students’ brief proposed an increase in funding for the Youth Employment Strategy, as well as the development of a strategy – modeled on the German Dual System of Vocational Education – to enhance employment and training opportunities for Canada’s youth. 3. “Increasing the Competitiveness of Canadian Businesses Through Research, Development, Innovation and Commercialization” WitnessesThe Confédération des syndicats nationaux called for a variety of changes to the Employment Insurance program. In particular, it said that at least 60% of contributors should be able to access benefits, maximum insurable earning thresholds should be revised, and the surplus in the Employment Insurance fund should be used for program enhancements. Moreover, it asked that a separate employment insurance fund be created, with this fund managed by the private sector. In mentioning the Australian Workforce and Productivity Agency, Polytechnics Canada requested the creation of an arm’s-length, independent labour market information council that would collect and supply labour market data to all Canadians. It also suggested that the proposed labour market information council monitor all apprentices in Canada, and provide information on their progress, their mobility and the barriers they face. The Confédération des syndicats nationaux suggested that the government adopt measures that would support the transition to an economy that creates “green” jobs. 4. “Ensuring Prosperous and Secure Communities, Including Through Support for Infrastructure” WitnessesThe Large Urban Mayors’ Caucus of Ontario called on the government to work with the provinces and municipalities to develop a comprehensive jobs strategy; the strategy would include a coordinated international trade agenda, targeted investments in transportation and transit infrastructure to address issues that affect economic growth and job creation, such as gridlock, and labour market measures, such as skills training, apprenticeship programs and changes to the immigration system. 5. “Improving Canada’s Taxation and Regulatory Regimes” WitnessesIn speaking about the Working Income Tax Benefit, Arthur Cockfield – who is with Queen’s University and appeared as an individual – proposed that benefits be paid for a longer period and at a higher amount. Noting that employees who earn slightly more than $2,000 annually do not qualify for Employment Insurance benefits and that two-thirds of those who are eligible for a refund of their contributions actually receive a refund, Restaurants Canada requested the creation of a basic exemption from the payment of contributions that would be similar to the year’s basic exemption in the Canada Pension Plan, and would apply to both employees and employers. |