FINA Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

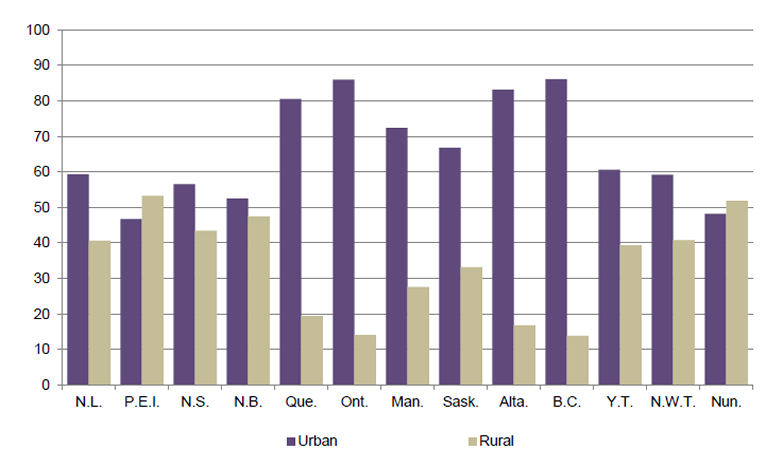

CHAPTER FIVE: ENSURING PROSPEROUS AND SECURE COMMUNITIES, INCLUDING THROUGH SUPPORT FOR INFRASTRUCTUREA. Background1. Urban and Rural CommunitiesSince 1851, the percentage of Canadians living in urban areas has been rising; it was 81.1% in 2011, representing approximately 27.1 million individuals. Nearly 11.6 million of these individuals – 34.5% of the population – were living in one of Canada’s three largest census metropolitan areas: Toronto, Montreal and Vancouver; a census metropolitan area must have a total population of at least 100,000 individuals, of whom 50,000 or more people must live in the area’s “core.” In 2011, 6.3 million people resided in Canada’s rural areas, a figure that has remained relatively stable since 1991. As the urban population has grown consistently over the last two decades, the proportion of Canadians living in rural areas has declined, falling from 23.4% in 1991 to 18.9% in 2011. As shown in Figure 9 for 2011, the proportion of the Canadian population living in rural areas was higher in the Atlantic provinces and the territories than in the rest of Canada; Canada’s four most populated provinces – Ontario, Quebec, British Columbia and Alberta – had the highest proportions of their residents living in urban areas. With the exception of Manitoba, the proportion of residents residing in rural areas has been decreasing in all provinces/territories since 1991; in Manitoba, the proportion has been stable. Figure 9 – Proportion of the Population Living in Urban and Rural Areas, by Province/Territory, 2011 (%)

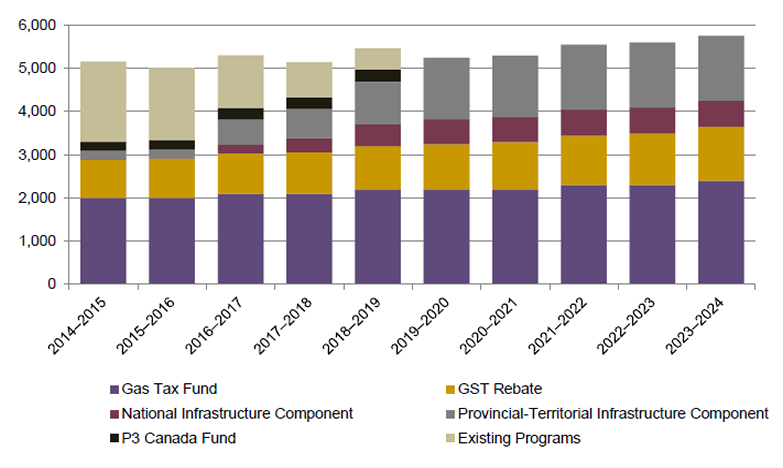

Notes: “Rural population” refers to persons living outside centres that have a population of 1,000 and outside areas that have 400 persons per square kilometre. “Urban population” refers to the remaining population. Source: Figure prepared using information from: Statistics Canada, “Population, urban and rural, by province and territory.” A number of federal departments, agencies and Crown corporations – such as the regional development agencies, Infrastructure Canada and the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation – support the development of prosperous and secure urban and rural communities, including through funding for infrastructure and affordable housing. 2. InfrastructurePublic infrastructure that is in good condition is thought to be essential to both the development of prosperous communities and the well-being of inhabitants. According to Infrastructure Canada, significant investments in core public infrastructure – bridges, roads, water and wastewater systems, public transit, and cultural and recreational facilities – by all levels of government have resulted in a decrease in that infrastructure’s “average age,” defined as the percentage of its useful life that is spent. That said, sustained investments are needed in order to maintain the quality and adequacy of public infrastructure. As most public infrastructure is owned by the provinces/territories and municipalities, the federal government’s role in relation to that infrastructure consists primarily in providing financial support for infrastructure projects. To that end, Infrastructure Canada administers a number of funding programs, although other federal departments and agencies also provide support. The 2013 federal budget proposed the New Building Canada Plan, which is a 10-year funding commitment for provincial/territorial and municipal infrastructure that covers the 2014–2015 to 2023–2024 period and replaces the Building Canada Plan. The plan has three key funds: the P3 Canada Fund; the Community Improvement Fund, which includes the Gas Tax Fund and the incremental Goods and Services Tax Rebate for Municipalities; and the New Building Canada Fund, which includes the National Infrastructure Component and the Provincial-Territorial Infrastructure Component, part of which is the Small Communities Fund. Figure 10 provides a breakdown of planned federal spending, through the New Building Canada Plan, for provincial/territorial and municipal infrastructure over the 2014–2015 to 2023–2024 period. Figure 10 – Planned Federal Spending through the New Building Canada Plan, 2014–2015 to 2023–2024 ($ millions)

Notes: “GST” means Goods and Services Tax.

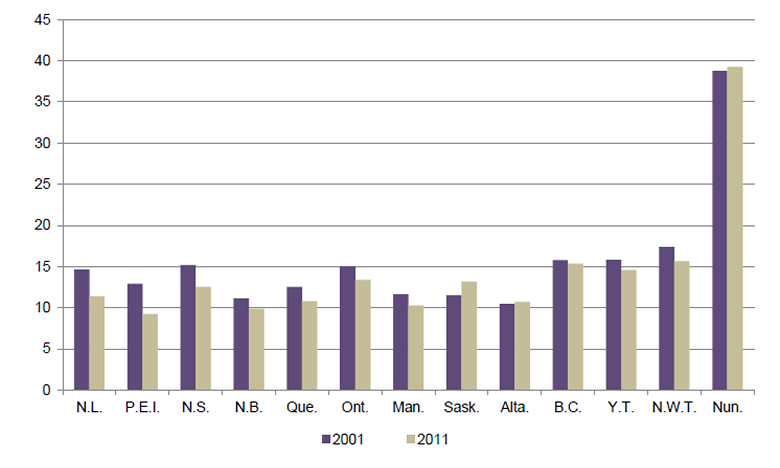

Source: Figure prepared using information from: Department of Finance, Jobs, Growth and Long-Term Prosperity – Economic Action Plan 2013, 21 March 2013, p. 178, and Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer, A Cost Estimate of Federal Infrastructure, 11 April 2013, p. 6. In addition to the funding provided for provincial/territorial and municipal infrastructure, the federal government owns and maintains a large portfolio of public infrastructure, including bridges, airports, ports and border infrastructure. All federal infrastructure projects with capital costs exceeding $100 million are subject to a public–private partnership screening process. Finally, the federal government also supports on-reserve First Nations public infrastructure through a number of programs administered by Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada. These programs include the Capital Facilities and Maintenance Program, the First Nations Infrastructure Fund and the First Nations Water and Wastewater Action Plan. 3. HousingAccording to the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, housing is “acceptable” when it is adequate in quality and suitable in size, and can be obtained without spending 30% or more of before-tax household income; households whose shelter does not satisfy these criteria and that are unable to access acceptable housing are considered to be in core housing need. The availability of acceptable housing can affect the well-being of individuals and communities, as it can positively affect health outcomes, educational achievement and labour market attachment. In 2011, the latest year for which data are available, the percentage of Canadian households that were considered to be in core housing need was 12.5%, down from 13.7% in 2001. As shown in Figure 11, in 2011, the proportion of households in core housing need was highest in Nunavut, followed by the Northwest Territories, British Columbia and Yukon; it was lowest in Prince Edward Island, followed by New Brunswick. Over the 2001–2011 period, Saskatchewan, Nunavut and Alberta were the only provinces/territories to have an increase in the proportion of households in core housing need. Figure 11 – Proportion of Households in Core Housing Need, by Province/Territory, 2001 and 2011 (%)

Source: Figure prepared using information from: Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, “Households in Core Housing Need, Canada, Provinces, Territories and Metropolitan Areas, 1991–2011.” Through the Investment in Affordable Housing initiative, the federal government provides funding to provinces/territories to support the design and delivery of affordable housing programs; the federal contributions are matched by provincial/territorial contributions. In addition, through the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, the federal government makes investments to support the federal portfolio of existing social housing on- and off-reserve; most of this housing was built between 1946 and 1993. Lastly, Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation’s Affordable Housing Centre provides advisory and financial services to private, public and not-for-profit developers to help them deliver new affordable housing projects without long-term federal financial assistance. Regarding support for affordable housing on-reserve, the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation delivers a number of initiatives, including the On-Reserve Non-Profit Housing Program and direct lending for eligible social housing projects. As well, Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada provides support for housing on-reserve. In order to prevent and reduce homelessness, the federal government provides financial and other support to communities across Canada – including Aboriginal and those that are remote – through the Homelessness Partnering Strategy. B. Changes Proposed by Witnesses Invited to Address “Ensuring Prosperous and Secure Communities, Including Through Support for Infrastructure”Witnesses invited by the Committee to speak about the topic of ensuring prosperous and secure communities, including through support for infrastructure, focused their remarks on funding programs for provincial/territorial and municipal infrastructure, federal procurement rules for infrastructure, public–private partnerships and other types of private-sector involvement in infrastructure. Moreover, they commented on electricity infrastructure, climate change adaptation and disaster mitigation, airport infrastructure and tourism, and housing and homelessness. 1. Funding Programs for Provincial/Territorial and Municipal InfrastructureIn highlighting the economic, social and environmental benefits of public transit, the Amalgamated Transit Union advocated permanent and dedicated funding for public transit, including through a share of the Gas Tax Fund, a portion of the Goods and Services Tax and/or an employer payroll tax. According to the Canadian Urban Transit Association, the government should work with the provinces and municipalities to increase the share of infrastructure funding that is allocated to public transit. Moreover, to improve the effectiveness of federal investments in public transit, it supported better integration of land-use planning into investment decisions and fiscal incentives to encourage the use of public transit. Recognizing that new federal regulations will require municipalities to upgrade their wastewater systems, the Federation of Canadian Municipalities requested a 20-year federal commitment to assist municipalities with the costs of these upgrades. It mentioned the creation of a fund dedicated to wastewater infrastructure projects that would receive contributions from all levels of government, including $300 million annually from the federal government. The Canadian Parks and Recreation Association noted the health and social benefits of recreational and sports infrastructure, and proposed that the federal government work with provincial and municipal governments to establish a program that would fund critical repairs, maintenance, adaptation or replacement of this type of infrastructure. According to it, the federal contribution to the program should be $925 million annually for three years. Regarding the New Building Canada Fund, the Saskatchewan Association of Rural Municipalities asked that applications for rural road and bridge projects that support the natural resources sector be considered in the context of their economic impact. Moreover, it proposed that a share of the Provincial-Territorial Infrastructure Component of the New Building Canada Fund be dedicated to rural communities, and that future federal infrastructure programs include a small communities component with a population threshold that is lower than that currently in place. The Union of Quebec Municipalities noted that the federal government and the Province of Quebec have not yet reached an agreement regarding the New Building Canada Fund; it encouraged them to do so promptly, as a number of New Building Canada Fund components – including the Small Communities Fund – have not yet been implemented in Quebec as a result of the lack of agreement. In commenting on the federal approach to investments in provincial/territorial and municipal infrastructure, the Mowat Centre advocated a more strategic and coordinated approach that better integrates provincial and municipal priorities, as well as a wide range of policy considerations. 2. Public–Private Partnerships and Other Types of Private-Sector Involvement in InfrastructureThe Canadian Council for Public-Private Partnerships encouraged the government to address a specific disincentive that exists when using a public–private partnership procurement process for a particular project: the maximum share contributed by the federal government to a project funded through the P3 Canada Fund is 25%, while it is 33% for the New Building Canada Fund. The Canadian Urban Transit Association advocated an increase in the maximum federal share in relation to the P3 Canada Fund from 25% to 33%. According to the Canadian Council for Public-Private Partnerships, municipalities and Aboriginal communities generally lack the capacity to participate in a public–private partnership project, which can be complex; consequently, it proposed the development of a “single window” that would provide integrated legal, technical and advisory services to these communities to help with the management of such a project. In noting that the complexity of a public–private partnership process results in up-front costs that are relatively high for small projects, the Canadian Life and Health Insurance Association proposed that P3 Canada develop standardized public–private partnership documentation for projects valued at less than $50 million. The Saskatchewan Association of Rural Municipalities suggested that modifications to the P3 Canada Fund eligibility criteria are needed in order to make it easier for rural communities to access funding. Regarding ways to stimulate private and/or pension fund investments in infrastructure, the Large Urban Mayors' Caucus of Ontario advocated changes to Canadian tax policy, while the Mowat Centre encouraged the government to involve pension funds as part of a national infrastructure strategy and to study other ways – including asset recycling, infrastructure banks and community benefit agreements – to fund infrastructure. KPMG supported adaptations to the Australian Asset Recycling Initiative to make it relevant for the Canadian context. 3. Federal Procurement Rules for InfrastructureIn suggesting that closed tendering in public procurement processes for construction projects restricts competitive bidding, which results in higher costs, Merit Canada called for a ban on closed tendering and the implementation of open tendering for federally funded projects, including those for infrastructure. According to it, competitive bidding processes are also undermined by "job targeting funds," which are used by unions to subsidize the wages paid by employers that hire unionized workers, thereby providing these employers with an unfair advantage over non-unionized employers against which they may be competing; it urged an examination of these funds by the Commissioner of Competition and the Canada Revenue Agency to determine whether they comply with the Competition Act and the Income Tax Act respectively. Marcelin Joanis – who is with Polytechnique Montréal and appeared as an individual – supported public procurement rules that reward innovation and that maximize the rate of return on each dollar invested in infrastructure. Noting the importance of academic research in this area, he urged governmental organizations to disclose more infrastructure-related data. 4. Electricity InfrastructureTo protect Canada’s electricity infrastructure better, the Canadian Electricity Association proposed an increase in funding for the Canadian Cyber Incident Response Centre. It also called for amendments to the Criminal Code to include new sentencing options for copper theft that would better reflect the potentially high damage that such theft can cause to electricity infrastructure. With a view to supporting R&D that contributes to the modernization of the electricity grid’s infrastructure, the Canadian Electricity Association requested the renewal of funding for the Clean Energy Fund and the ecoENERGY Innovation Initiative. 5. Climate Change Adaptation and Disaster MitigationIn speaking about the need for governments and businesses to improve the extent to which they anticipate and adapt to extreme weather events, the Canadian Climate Forum advocated the development of a better understanding of changing weather patterns and climatic trends, and supported increased investments in that regard. In particular, it proposed extending and/or increasing the funding for the Climate Change and Atmospheric Research program. The Canadian Climate Forum and the Large Urban Mayors’ Caucus of Ontario urged the development of infrastructure planning strategies that incorporate adaptation to climate change. To that end, the Large Urban Mayors’ Caucus of Ontario called for additional investments in storm water and electricity infrastructure to improve resistance to extreme weather events, while the Canadian Climate Forum proposed the creation of incentives to encourage governmental organizations, businesses and communities to incorporate the concept of “climatic resilience” in their strategic planning. The Canadian Electricity Association requested that funding for Natural Resources Canada’s Adaptation Platform be renewed. The Saskatchewan Association of Rural Municipalities urged the creation of a national disaster mitigation program which, with funds of $200 million over five years, would finance structural and non-structural mitigation projects; structural projects would include the construction of dykes, the raising of properties and the digging of flood diversion channels, while non-structural projects would include flood mitigation strategies. It also asked that municipally owned gravel be included as an eligible expense for cost-sharing in relation to the Disaster Financial Assistance Arrangements’ guidelines. 6. Airport Infrastructure and TourismIn noting that funding for the Canadian Air Transport Security Authority has not kept pace with growth in the number of air passengers, the Canadian Airports Council proposed that funding for the authority be adjusted accordingly. It also requested that funding for the Canada Border Services Agency be increased to allow the deployment of additional automated border clearance kiosks, and that support for trusted traveller programs – such as NEXUS – be increased. As well, the Canadian Airports Council called for changes to the Airports Capital Assistance Program that would make small National Airport System airports eligible for funding. The Canadian Airports Council also urged a comprehensive study of taxes and fees in relation to air travel and their impacts on the competitiveness of Canadian airports. While the Canadian Airports Council said that these taxes and fees should not be increased further, the Tourism Industry Association of Canada indicated that they should be reduced. In noting that growth in the tourism sector has been much lower in Canada than in other countries, the Tourism Industry Association of Canada requested annual investments of $35 million for three years in a national marketing campaign designed to attract visitors from the United States. 7. HousingThe Federation of Canadian Municipalities and the Large Urban Mayors' Caucus of Ontario encouraged the government to maintain or expand funding for affordable housing. The Wellesley Institute proposed a doubling of the funding for the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation’s Investment in Affordable Housing initiative, and requested that the government reverse the decline in its support for affordable housing. Moreover, the Large Urban Mayors' Caucus of Ontario suggested that tax measures to support home ownership by low-income families be explored, while the Wellesley Institute called for a 10% increase in the funding for the Homelessness Partnering Strategy. In speaking about ways in which the government could make home ownership more affordable, the Canadian Home Builders' Association proposed a number of measures: maintain federal spending on core municipal infrastructure, as the result is lower municipal taxes; exempt provincial and municipal taxes on new homes from the Goods and Services Tax; and increase the maximum amortization period for government-backed insured mortgages to 30 years for qualified first-time home buyers. Regarding the home renovation sector, the Canadian Home Builders' Association advocated the creation of a tax credit for home renovation that would combat the underground economy in that sector. It also supported reinstatement of the ecoENERGY Retrofit-Homes program. C. Changes Proposed by Witnesses Invited to Address Topics Other Than “Ensuring Prosperous and Secure Communities, Including Through Support for Infrastructure”The Committee’s witnesses were invited to speak about a particular topic. When they appeared, they often made comments about one of the other five topics selected by the Committee, as indicated below. 1. “Balancing the Federal Budget to Ensure Fiscal Sustainability and Economic Growth” WitnessesAs a means of supporting economic growth, the Canadian Council of Chief Executives, the Conference Board of Canada and the University of Ottawa’s Kevin Page supported increased federal investments in infrastructure. 2. “Supporting Families and Helping Vulnerable Canadians by Focusing on Health, Education and Training” WitnessesAs part of its efforts to secure additional funding for First Nation reserves, including for housing, the Assembly of First Nations urged First Nations and the federal government to implement a funding framework that respects and fulfills First Nations treaty and inherent rights and that responds to the needs of its people. YWCA Canada stated that the shift of major funding from the former Homelessness Partnering Secretariat – operated through Human Resources and Skills Development Canada – to the Housing First model – a federally funded research demonstration project – needs to be accompanied by a gender-based analysis and resulting strategy to ensure the model is adapted to fit women's homelessness. 3. “Increasing the Competitiveness of Canadian Businesses Through Research, Development, Innovation and Commercialization” WitnessesThe Confédération des syndicats nationaux urged the government to adopt measures that would support the transition to an economy that produces fewer greenhouse gas emissions. 4. “Maximizing the Number and Types of Jobs for Canadians” WitnessesIn stating that public infrastructure projects are largely self-financing, the Canadian Labour Congress suggested that initial investments in such projects could be financed by increasing the federal corporate income tax rate to 19.5%. In its brief, the Canadian Chamber of Commerce called for a long-term federal infrastructure strategy that would ensure predictable and transparent funding, encourage the use of asset management plans, increase coordination with the provincial/territorial governments and the private sector, and focus on areas that produce the highest returns on investment for businesses and governments, such as trade-enabling infrastructure. To support communities, the Green Budget Coalition proposed a tax credit of up to $3,000 to assist with renovation costs when a certified agent ascertains that the radon in a home presents a health risk. To examine, assess and identify mechanisms to ensure equitable environmental protection and benefits, its brief requested funding of $30 million over three years for a commission of inquiry on ensuring healthy environments for Canadians, and $30 million annually for a federal-provincial/territorial committee and a federal office of environmental health equity. The Green Budget Coalition also suggested that the government fund fast-charging stations for electric vehicles around major urban centres, provide accelerated capital cost allowance rates for all forms of power storage, and integrate environmental adaptation considerations into all infrastructure project planning and assessment under the Building Canada Plan. In indicating that the government’s borrowing costs are currently very low, Scott Clark – who is with C.S. Clark Consulting and appeared as an individual – supported the creation of a new national infrastructure strategy that would be financed through borrowing; such a strategy could potentially include partnerships with pension funds. As well, to facilitate provincial investments in infrastructure, he advocated the creation of a federal financing agency that would lend to the provinces at federal borrowing rates. The Quebec Employers’ Council’s brief urged the federal and Quebec governments, as well as local stakeholders, to collaborate on appropriate financing solutions for major infrastructure projects in Quebec; in its view, the use of public–private partnerships should be explored. In mentioning the 2013 report entitled Forging Partnerships, Building Relationships, the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers’ brief highlighted the need for the government to consult with Aboriginal communities in a manner consistent with the recommendations in that report. In its view, reconciliation needs to occur among Aboriginal communities, industry and all governments in Canada to address land claims issues and to engage Aboriginal entrepreneurs in resource development projects. Solidarité rurale du Québec requested that, in development and employment assistance programs for training or support for business innovation, the government consider community size, population density, the types of natural resources, remoteness from major centres, and accessibility to services and infrastructure. It also proposed that, as part of a possible federal rural policy, the government establish an agreement with each regional county or municipality to strengthen and support rural development through decentralized financing; the rural pact in Quebec's national policy on rurality was cited as a possible model. In addition, Solidarité rurale du Québec urged the government to support local businesses and rural community development by limiting free trade with international agricultural markets, investing in the local forest biomass sector, and increasing local access to affordable, high-speed Internet. |