Chapter 6The Physical and Administrative Setting

The Chamber

The South Corridor, where the portraits of former Prime Ministers are displayed, links Confederation Hall to the Commons Chamber. At the west end of the corridor is the spacious high-ceilinged foyer of the House of Commons, which may also be accessed from the Members’ entrance at the western end of the Centre Block. On the four walls of the foyer, just below the balcony which overlooks it from the floor above, is a frieze comprised of 10 sets of low and high relief sculpture panels depicting events and themes from the past 25,000 years of Canadian history, from the arrival of the aboriginal peoples to that of the United Empire Loyalists in the late 18th century.33 Opening off the foyer are the doors to the House of Commons ante-chamber which leads into the Chamber itself. The doors, known as the Canada Doors, are made of white oak and trimmed with hand-wrought iron. The Canada Doors are usually open only for the Speaker’s Parade, the Speech from the Throne, and Royal Assent ceremonies. Members access the ante-chamber by using the smaller doors on either side of the Canada Doors. A second set of doors in the ante-chamber lead into the Chamber, while doors on the west and east sides lead into the government and opposition lobbies. The lobbies also open onto the Chamber.34

Each day when the House meets to conduct business, the Speaker’s Parade35 leaves the Speaker’s office and passes through the Speaker’s Corridor, the Hall of Honour, Confederation Hall and the South Corridor. The Parade enters the ante-chamber of the House through the Canada Doors and proceeds into the Chamber.

The Chamber itself is rectangular in shape, measuring approximately 21 metres in length and 16 metres in width. It is sheeted with Tyndall limestone as well as white oak and, like its counterpart at Westminster, is decorated in green36 (see Figure 6.3, “The House of Commons Chamber”). The 14.7-metre high ceiling is made of cotton canvas, hand-painted with the provincial and territorial coats of arms.

The floral emblems of the 10 provinces and 2 of the territories are depicted in 12 stained glass windows on the east, west and north walls of the Chamber.37 On the east and west walls, above the Members’ galleries and between the stained glass windows, is the noted British North America (BNA) Act series of sculptures. It consists of 12 separate bas-relief sculptures in Indiana limestone. Each one depicts, in symbolic and story form, the federal and provincial roles and responsibilities arising out of the BNA Act (now called the Constitution Act, 1867).38

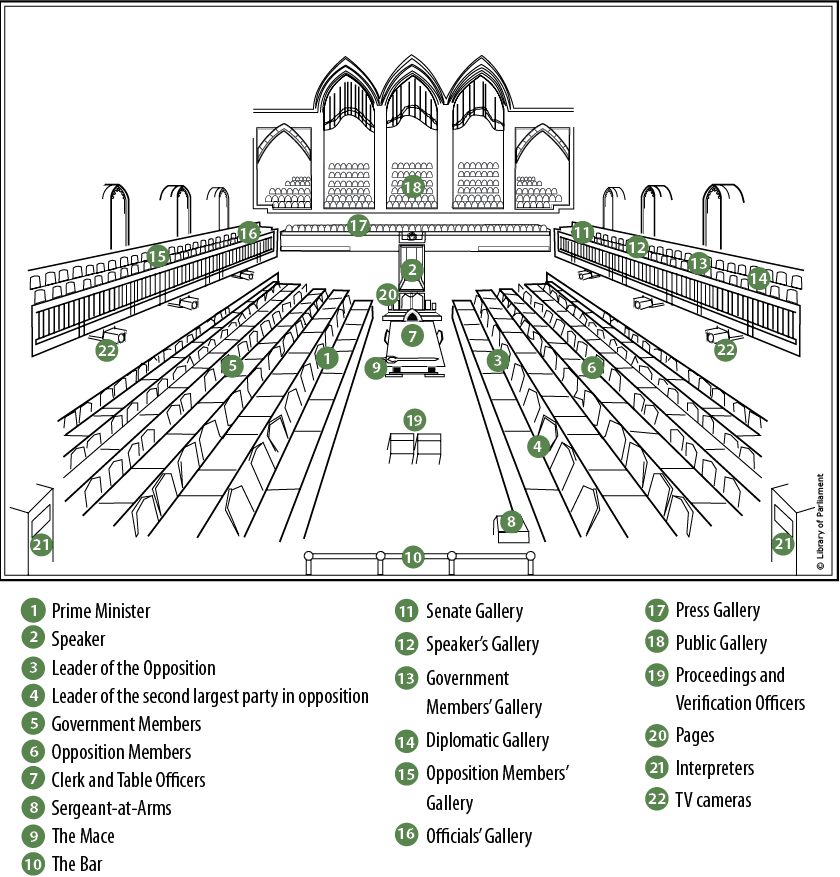

Seating

The Chamber is divided by a wide central aisle and is furnished on either side with tiered rows of desks and chairs, facing into the centre. The desks are equipped with a locked compartment (in which Members may store belongings), microphones, an electrical outlet and access to the House of Commons computer network. Government Members sit to the Speaker’s right, opposition Members to the left.39 The Prime Minister and Cabinet sit in the front rows of the government side; directly across the floor from the Prime Minister sits the Leader of the Opposition who is flanked by Members of his or her party. The second-ranked opposition party and all other recognized parties in the House sit with their leaders usually to the left of the Official Opposition, closer to the Bar of the House. Traditionally, the front-row seats to the left of the Speaker are reserved for leading Members of the opposition parties, and opposition parties are allocated front-row seats in proportion to their numbers in the House.40 The distance across the floor of the House between the government and opposition benches is 3.96 metres. When there are more government Members than can be accommodated on the Speaker’s right, some are seated on the left, usually in the seats closest to the Speaker. Similarly, when there are more opposition Members than can be accommodated on the Speaker’s left, the remaining opposition Members are seated on the right, closer to the Bar of the House. Members of parties not recognized in the House and independent Members are assigned seats by the Speaker.

All Members of Parliament have their own assigned seats in the Chamber. Should the number of seats in the House be increased following a decennial census, additional desks are installed.41 The allocation of seats in the House is the responsibility of the Speaker and is carried out in collaboration with the party Whips.42 Seat assignments may change from time to time, but the Prime Minister and the Leader of the Opposition are always seated in the same places. It is customary for seats to be assigned near the Chair for the use of the Deputy Speaker and other Chair Occupants when they are not presiding over the House; no such allocation is made for the Speaker.43

The Speaker’s Chair

The Speaker’s chair stands on a dais44 at the north end of the Chamber with the flag displayed to the right of the Speaker.45 In the years after Confederation, it was the custom for departing Speakers to take their chairs with them and a new chair to be made for the incumbent.46 This custom ceased in 1916 when the chair then in use was destroyed in the fire. A new chair arrived in 1921 as a gift from the British branch of what is now the Commonwealth Parliamentary Association.47 This chair is an exact replica of the original Speaker’s chair at Westminster designed by Augustus Pugin, made circa 1849, and then destroyed when the British House of Commons was bombed during the Blitz in 1941. It is approximately four metres high, surmounted by a canopy of carved Austrian oak and the Royal Coat of Arms. The oak used for the carving of the Royal Arms was taken from the roof of Westminster Hall, which was built in 1397.

Over the years, the Speaker’s chair and screen behind it have been modified. Microphones and speakers have been installed and lights placed overhead while the chair’s original black leather upholstery has been replaced with green velvet. The armrests now offer a writing surface and a small storage space. A hydraulic lift was also installed to permit more comfortable seating for the various occupants of the chair.48 At the foot of the chair, visible only to its occupant, is a computer screen which allows the Chair Occupant to see information generated by the computers at the Table, the countdown timer used to monitor the length of speeches and interventions when time limits apply, and a portion of the unofficial rotation list for Members wishing to speak. The screen also displays a digital feed from the television cameras in the Chamber, allowing the Speaker to see the image being broadcast.49

At the foot of the dais below the Speaker’s chair is a bench where some of the House of Commons pages are stationed during sittings of the House. The pages are first-year university students employed by the House of Commons to carry messages and deliver documents to Members during sittings of the House.50

A door behind the Speaker’s chair opens onto a corridor, called the Speaker’s Corridor, leading directly to the Speaker’s chambers. Hanging in this hallway are portraits of past Speakers of the House.51

The Table

A short distance in front of the dais and the Speaker’s chair is a long oak table where the Clerk of the House, chief procedural adviser to the Speaker, sits with other Table Officers.52 The Clerk sits at the north end of the Table, with Table Officers along its right- and left-hand sides. The Clerk’s chair was made in 1873. After the death in 1902 of the then Clerk, Sir John Bourinot, the chair was presented to his widow. In 1940, the family gifted it to the House.

Each of the three seating positions at the Table is equipped with a computer providing full network connectivity. The computers are used to keep the records,53 to manage the rotation lists of Members wishing to speak, to relay information to the Chair and to send and receive electronic mail to and from other branches of the House. The computers also have access to the digital feed from the television cameras in the Chamber. The Mace rests at the south end of the Table. Also on the Table is a collection of parliamentary reference texts for consultation by Members and Table Officers, as well as a pair of bookends, a calendar stand, inkstand and seal press.54

The Mace

The Mace is the ornamental staff, symbol of the authority of the Speaker, which rests on the Table during sittings of the House. In the Middle Ages, the Mace was an officer’s weapon; it was made of metal with a flanged or spiked head and was used to break through chain-mail or plate armour.55 In the 12th century, the Sergeants-at-Arms of the King’s Bodyguard were equipped with maces. These maces, stamped with the Royal Arms and carried by the Sergeants in the exercise of their powers of arrest without warrant, became recognized symbols of the King’s authority. Maces were also carried by civic authorities.

Royal Sergeants-at-Arms began to be assigned to the Commons early in the 15th century. By the end of the 16th century, the Sergeant’s mace had evolved from a weapon of war to an ornately embellished emblem of office. The Sergeant-at-Arms’ power to arrest without warrant enabled the Commons to arrest or commit persons who offended them without having to resort to the ordinary courts of law.56 This penal jurisdiction is the basis of the concept of parliamentary privilege and, since the exercise of this privilege depended on the powers vested in the Royal Sergeant-at-Arms, the Mace—his emblem of office—was identified with the growing privileges of the Commons and became recognized as the symbol of the authority of the House and of the Speaker through the House.57

At Confederation, the House of Commons Mace was that of the former Legislative Assembly of the Province of Canada.58 It had survived the burning of the Parliament building in Montreal in 1849,59 as well as two fires in Quebec City in 1854,60 but was lost in the great fire of February 3, 1916. When the House met in the Victoria Memorial Museum (as it was then known) in the immediate aftermath of the fire, the Senate lent the House its Mace. For the following three weeks, the Mace belonging to the Ontario Legislature was used until a temporary Mace, made of wood, was fashioned. The current Mace is made of sterling silver and copper alloy covered with heavy gilt, is 1.48 metres long and weighs 7.9 kilograms. It was a gift from the Lord Mayor and the Sheriffs of London and was presented to Prime Minister Robert L. Borden at The Guildhall in London on March 28, 1917 and first used in the House on May 16, 1917.61 The wooden Mace was kept and since 1977 has been used in the Chamber on the anniversary of the date of the fire.62

The Mace is integral to the functioning of the House; since the late 17th century it has been accepted that the Mace must be present for the House to be properly constituted.63 The guardian of the Mace is the Sergeant-at-Arms,64 who carries it on the right shoulder in and out of the Chamber at the beginning and end of each sitting of the House.65 At the opening of a sitting of the House, the Mace is laid across the foot of the Table with its crown pointing to the government side of the House. When the House sits as a Committee of the Whole, it is placed on brackets below the foot of the Table.66 During the election of a Speaker, the Mace rests on a cushion on the floor beneath the Table. During a sitting, it is considered a breach of decorum for Members to pass between the Speaker and the Mace.67 Members have also been found in contempt of the House for touching the Mace during proceedings in the Chamber.68 When the House is adjourned, the Mace is kept in the Speaker’s office.

The Bar of the House

The Bar is a brass rod extending across the floor of the Chamber inside its south entrance. It is a barrier past which uninvited representatives of the Crown (as well as other non-Members) are not welcome.69 The Sergeant-at-Arms, or an assistant, sits at a desk on the opposition side of the Chamber and inside the Bar.

Individuals may be summoned to appear before the Bar of the House in order to answer to the authority of the House. If someone is judged to be in contempt of the House, that is, guilty of an offence against the dignity or authority of Parliament, the House may summon the person to appear and order that he or she be reprimanded by the Speaker in the name of and with the full authority of the House. On a number of occasions in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, individuals were summoned to appear before the Bar of the House. Since 1913, there have been only two instances of the House requiring someone to appear at the Bar to be reprimanded.70

On occasion, individuals may be summoned to the Bar for reasons other than to be admonished by the Speaker. Witnesses to be examined by the House may stand at the Bar and reply to questions posed by Members.71 As well, the House may call individuals to the Bar in order to pay tribute to them.72

The Galleries

Overlooking the floor of the House on both sides and at both ends of the Chamber are galleries which can accommodate more than 500 people (see Figure 6.3, “The House of Commons Chamber”). In the gallery facing the Speaker’s Chair, called the South Gallery,73 the first rows are reserved for the diplomatic corps and for other distinguished guests; the remaining rows are reserved for the visiting public. At the opposite end of the Chamber, immediately above the Speaker’s Chair, is the Press Gallery. Admittance is restricted to members of the Parliamentary Press Gallery74 (one of the galleries in which note-taking is permitted). Immediately behind the Press Gallery is another public gallery.75 On the side of the Chamber facing the government benches are three galleries: one for guests of government Members, another for Senators and their guests, and another one for guests of the Prime Minister and the Speaker. On the other side of the Chamber, facing the opposition benches, a gallery is reserved for departmental officials (the other gallery in which note-taking is permitted), another for guests of the Leader of the Opposition, and two others for guests of Members of other opposition parties.

The doors to the galleries are opened at the start of each sitting of the House, after the prayer is read.76 For reasons of decorum and security, photography, reading and sketching materials, and note-taking (with the above exceptions) are not permitted in the galleries. Coats, briefcases, notebooks, photographic equipment and the like may not be carried into the galleries.77 During the taking of recorded divisions, no one may enter or leave the galleries.

Strangers

“Stranger” is a term of long-time use in the procedural lexicon; it refers to anyone who is not a Member or an official of the House of Commons (for example, Senators, diplomats, government officials, journalists or members of the general public). It underlines the distinction between Members and non-Members and gives emphasis to the fact that strangers or outsiders may be present in the galleries or within the House precincts only under the authority of the House.78 Strangers are not permitted on the floor of the House of Commons when the House is sitting.79

The right of the House to conduct its proceedings in private, that is, without strangers present, is centuries old. Until 1845 in the British House, sessional orders excluded strangers from every part of its premises (while in practice the presence of strangers came to be tolerated in areas not appropriated to the exclusive use of Members).80 In Canada, at Confederation, the House adopted a rule giving individual Members the power to order the galleries to be cleared.81 In 1876, the rule was substantially amended to allow Members only to move a motion “that strangers be ordered to withdraw”; this non-debatable and non-amendable motion was then left for the House to decide.82 Since 1994, in addition to Members being allowed to move the motion, the Speaker has had the authority to order the withdrawal of strangers without putting the question to the House.83 In practice, such occurrences are not frequent and strangers are welcomed so long as there is space to accommodate them and proper decorum is observed.

Disorder in the Galleries

The Parliamentary Protective Service is responsible for maintaining order and decorum in the galleries. From time to time there have been instances of misconduct in the galleries and the security staff have acted to remove demonstrators or strangers behaving in a disruptive way.84 In cases of extreme disorder, the Speaker has directed that the galleries be cleared.85 In addition, should the House adopt the motion “That strangers be ordered to withdraw”, it would be the duty of the security staff to clear the galleries of strangers.

Lobbies

Adjacent to the government and opposition sides of the Chamber is a long, narrow room known as a lobby. The one behind the government benches is reserved for government Members; the other, on the opposition side, is for Members of the opposition parties. Connected by doors to the Chamber, the lobbies are furnished with tables, armchairs and office equipment for Members’ use. Members attending the sitting of the House use the lobbies to conduct business and are able to return to the Chamber at a moment’s notice. The party Whips assign staff to work from the lobbies and pages are stationed in the lobbies to answer telephones and carry messages. The lobbies are not open to the public. Security staff control access to the lobbies in accordance with guidelines set by the Corporate Security Office after consultation with the Whips.

Sound Reinforcement, Simultaneous Interpretation and Broadcasting Systems

In 1951, a special committee of the House recommended the installation of a sound reinforcement system “similar to the one in the House of Commons Chamber at Westminster”.86 For some years, there had been complaints about the acoustics in the Chamber and the difficulty that Members and those in the galleries had in following the proceedings. The challenge in providing effective sound amplification lay in devising a system for use in an assembly where Members speak from their places (rather than from a rostrum) and only when recognized by the Speaker. The committee’s report was concurred in; the system was installed during a recess and used for the first time in the session which opened on November 20, 1952.87 Each Member’s desk, as well as the Speaker’s Chair, is equipped with a microphone. A microphone switching console, staffed by console operators, is located at the front of the gallery at the south end of the Chamber. Individual microphones are activated when a Member is recognized by the Speaker. Only the Speaker has the power to activate his or her own microphone (it may also be activated by the console operator); when the Speaker’s microphone is activated, the Members’ microphones will not function.

In 1958, the House agreed to the installation in the Chamber of a system for simultaneous interpretation in both official languages.88 Members were of the opinion that this would give further expression to the Constitution, which provides for the equal status of the official languages and for their use in parliamentary debate.89

Enclosed booths for interpreters are located in the southeast and southwest corners of the Chamber opposite the Speaker’s chair. Members’ desks are equipped with earphones in order to receive floor amplification, as well as simultaneous interpretation of the proceedings into French or English. Visitors in the galleries also have access to the sound reinforcement and interpretation systems and may choose to listen to the proceedings with interpretation in the official language of their choice, or without interpretation.

In 1977, the House decided to televise its proceedings.90 Following this decision, the Chamber became the site of extensive construction to equip it for this purpose. During the summer adjournment, the Chamber was refitted: the sound systems were upgraded, appropriate lighting was installed, cameras were added (operated manually and later replaced with remote-controlled cameras), and a control room was constructed above the South Gallery situated at the south end of the Chamber.91 In 2003, the House approved the broadcast of its proceedings over the Internet via the House of Commons website.92 Since then, sittings of the House, televised committee meetings, and the audio feed from non-televised committee meetings have been broadcast over the Internet.93

Since 2003, technological upgrades have been made to the Chamber during adjournment periods. The simultaneous interpretation system, broadcasting infrastructure and sound systems have all undergone various upgrades.94 New technology such as Wi-Fi has also been made available so that Members may conduct business from the lobbies more easily.

Provision for Still Photography

Before the advent of broadcasting of House of Commons proceedings, photographs of the House during a sitting were taken with the permission of the House.95 In the late 1970s, once the House had dealt with the question of broadcasting, the matter of still photography arose. There were no provisions for print media to take pictures of the House at work, except by special arrangement, whereas the electronic media now had access to images of every sitting of the House.96 On a trial basis, and now standard practice,97 a photographer was allowed behind the curtains on each side of the House during Question Period, as well as for other important debates. The photographers are employed by a news service agency which supplies other news organizations under a pooling arrangement. When in the Chamber, they operate in accordance with the principles governing the use of television cameras, described in Chapter 24, “The Parliamentary Record”. Only these photographers, and the official photographers employed by the House of Commons, are authorized to take photographs of the Chamber while the House is in session; even Members are forbidden from taking photographs.98

Other Uses of the Chamber

At times, the House of Commons Chamber is used for purposes other than a parliamentary sitting. Some are recurring events such as addresses by distinguished visitors,99 orientation sessions for new Members,100 and educational and other programs.101 At other times, the Chamber has been used for special events.102 Since these events are not actually sittings of the House, the Mace is not on the Table.