OGGO Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

STRENGTHENING THE PROTECTION OF THE PUBLIC INTEREST WITHIN THE PUBLIC SERVANTS DISCLOSURE PROTECTION ACTEXECUTIVE SUMMARYOn 2 February 2017, the House of Commons Standing Committee on Government Operations and Estimates (the Committee) decided, at the request of the President of the Treasury Board, to conduct the first statutory review of the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act (PSDPA) since its implementation in 2007. In the course of its study, the Committee held a total of 12 meetings, heard from 52 witnesses and received 12 briefs. The Committee reviewed the origins and the objectives of the PSDPA, the disclosure procedures it prescribes, and the Canadian experience under the Act as well as foreign whistleblower protection legislation and internationals best practices. The report features a holistic presentation of the main procedural challenges and successes of the Act in protecting whistleblowers and strengthening accountability and the integrity of the public service. The report also analyzes in depth many challenges and includes 15 recommendations to improve the Act in its objects and processes to ensure the integrity of the public sector and the protection of Canadian whistleblowers. In the opinion of the Committee, the six main challenges are the following:

The Committee’s recommendations seek to address these challenges by:

On 13 September 2016, the President of the Treasury Board, the Honourable Scott Brison, asked the House of Commons Standing Committee on Government Operations and Estimates (the Committee) to conduct the review provided for in the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act (PSDPA), which came into force in 2007. On 2 February 2017, the Committee decided to undertake this study and adopted the following motion to that effect: That the Committee undertake a review of the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act. The PSDPA was the result of a series of actions taken with regard to the disclosure of wrongdoing in the public sector and the protection of public servant whistleblowers. Since as early as 1996, there have been task forces, policies, codes, reports and government and private members’ bills dealing with the subject. However, the conclusions of an Auditor General of Canada’s November 2003 report, and those of the commission of inquiry that was subsequently established to study the Sponsorship Program from 1997 to 2001 and the federal government’s advertising activities from 1998 to 2003 highlighted the need to better protect public servants who want to disclose wrongdoings in the federal public service.[1] In November 2005, the Parliament of Canada adopted the PSDPA. In 2006, prior to its coming into force, the PSDPA was substantially amended by the Federal Accountability Act. The PSDPA came into force on 15 April 2007 and established disclosure procedures for wrongdoing and related complaints of unlawful reprisals in the public service, Crown corporations[2] and other federal public bodies. It also replaced the Treasury Board’s Policy on the Internal Disclosure of Information Concerning Wrongdoing in the Workplace.[3] From February to April 2017, the Committee held 12 meetings to study the PSDPA and heard from 52 witnesses including:

The full list of witnesses is available in Appendix A and the list of briefs submitted is found in Appendix B. The Committee’s statutory review report of the PSDPA consists of an overview of the provisions of the law and identified flaws, the suggested solutions brought forward by witnesses and experts, and finally the Committee’s observations and recommendations. Part I of the report reviews the disclosure of wrongdoing process, the types of protections offered to whistleblowers and the associated corrective measures. Part II analyzes in depth the protection provisions for whistleblowers under the Act as well as the remedial process in the event reprisals occur. Part III explores the federal organizational culture with respect to whistleblowing, and examines methods to improve it. Finally, part IV evaluates the objects of the Act, the reporting provisions of the Act and how proactive the law is to prevent wrongdoing in order to maintain confidence in the integrity of the federal public sector. Although some witnesses called for the Act to be completely redrafted, the Committee has opted for an incremental legislative approach regarding the recommendations contained in this report. However, the Committee wishes to encourage those undertaking the next statutory review of the PSDPA, no later than five years from now, to explore the following themes, as well as whether the implementation of a restorative justice approach is appropriate in this context:

1.1 Provisions of the Act Concerning the Disclosure of Wrongdoing1.1.1 What May Be Disclosed1.1.1.1 The Definition of WrongdoingThe PSDPA seeks to maintain and enhance public confidence in the integrity of public servants and public institutions through effective procedures for the disclosure of wrongdoings and the protection of public servants who make such disclosures. The PSDPA strives to achieve an appropriate balance between public servants’ duty of loyalty to their employer, their right to freedom of expression as guaranteed by the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, and the public interest.[4] Section 8 of the Act, defines wrongdoing in or relating to the public sector as:

According to Brian Radford, General Counsel, Office of the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner of Canada (the Commissioner’s Office), it is the view of the Commissioner’s Office − an independent and confidential channel to enable public servants and members of the public to disclose potential wrongdoing in the federal public sector − that the definition of “wrongdoing” is broad and provides the flexibility to fully investigate matters brought to its attention. He indicated that: The public interest importance of the act means that the act is there to address wrongdoing of an order of magnitude that could shake public confidence, if not reported and corrected. When the Commissioner is dealing with an allegation of wrongdoing, it is something that if proven involves a serious threat to the integrity of the public sector. Joe Friday, Commissioner, Commissioner’s Office, supports that his Office “deal[s] with everything from human behaviour and interactions to potential crime.” However, as it does not have criminal jurisdiction, criminal acts of wrongdoing investigated by the Commissioner’s Office are referred to the RCMP. Accordingly, the Commissioner’s Office has referred cases of wrongdoing to the RCMP at least four times.[5] Regarding the disclosure of wrongdoing, as defined by the Act, Carl Trottier, Assistant Deputy Minister, Governance, Planning and Policy Sector, Treasury Board Secretariat, and Barbara Glover, Assistant Deputy Minister, Departmental Oversight Branch, Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC),[6] emphasized that disagreement with policy or disagreement with implementation is not necessarily equivalent to wrongdoing. Nonetheless, it was expressed by Craig MacMillan, Assistant Commissioner, Professional Responsibility Officer, RCMP, that the type of wrongdoing a public servant may be guilty of committing varies depending on its institution of employment. For example, he noted that an RCMP member would be found to have committed a wrongdoing for breaching its code of conduct under the Act even if it is not a serious breach. 1.1.1.2 When Is Wrongdoing Serious Enough?Disclosure activity statistics demonstrate that very few disclosures of wrongdoing, 25% to 32%,[7] warrant an investigation under the PSDPA, on average, by the Commissioner and within the departments and agencies, respectively. Mr. Trottier explained that “in many instances [the disclosures made internally] do not meet the definition of wrongdoing in any shape or form. In other instances, [disclosures] should have been sent through another means, another grievance process.” For example, Marc Thibodeau, Director General, Labour Relations and Compensation, Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA), submitted that CBSA had received 93 allegations of wrongdoing in 2015-2016, but that 46 of these “did not meet the threshold for investigation under the Act [and another] 23 were referred to other processes.” Mr. MacMillan and Mr. Thibodeau claimed that the PSDPA is meant to address wrongdoing of a more “serious” nature and is a “last resort mechanism for issues that are not covered by other [processes]. In that context, a lot of issues were raised and resolved through other processes.” Nonetheless, John Tremble, Director, Centre for Integrity, Values and Conflict Resolution, Department of Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada, indicated that all disclosures are subject to a “rigorous analysis” to determine their merit under the Act. In response to a question from a Committee member, Mr. Friday sustained that the Commissioner’s Office found a low number of wrongdoings due to the level of seriousness the term’s definition reflects. The Committee also invited international experts to compare and comment on the similarities and differences between the PSDPA and other whistleblower protection laws. Definitions of wrongdoing from selected jurisdictions are presented in Table 1. Table 1 – Definition of the Term ‘Wrongdoing’ from Selected Jurisdictions’ Legislation on Whistleblower Protection

Sources: Table prepared using data obtained from Australian Capital Territory Government, Public Interest Disclosure Act 2012; U.S. Government, Whistleblower Protection Act of 1989; Government of Ireland, Protected Disclosures Act 2014; and U.K. Government, Public Interest Disclosure Act 1998. Notwithstanding the similarities between the different definitions, Mark Worth, Manager, Blueprint for Free Speech, testifying as an individual, recognized that there may be an issue as no “provision in the [PSDPA] distinguishes rampant, systemic, or across-the-board workplace problems like discrimination, unsafe conditions at work, or bullying from individual employee grievances.” In addition, the Committee heard from many witnesses, such as Debi Daviau, President, Professional Institute of the Public Service of Canada, that the definition of wrongdoing is actually “too narrow.” In agreement, David Yazbeck, Partner, Raven, Cameron, Ballantyne & Yazbeck LLP, appearing as an individual, said that the law is interpreted such that “gross mismanagement” is a wrongdoing, but “mismanagement” is not. Larry Rousseau, Executive Vice-President, National Capital Region, at the Public Service Alliance of Canada, concurs that the Act does not ensure a whistleblower the right to disclose all acts of illegality and misconduct. According to him, the definition of “wrongdoing” selectively omits large areas, including the Treasury Board’s policies. Moreover, John Devitt, Chief Executive, Transparency International Ireland, testifying as an individual, explained that the impact of a limiting definition of wrongdoing is that it would not afford protection to public servants that disclose potential wrongdoing outside that definition. Another limitation of the definition, in the opinion of Patricia Harewood, Counsel, Public Service Alliance of Canada, is that the definition of wrongdoing under section 8 of the Act restricts its application to the public sector as defined under the Act. 1.1.2 To Whom May a Disclosure Be Made?1.1.2.1 Internal Disclosure ProceduresSections 10 and 12 of the PSDPA establish the first of two channels for the disclosure of wrongdoings in the federal public sector: the internal disclosure procedures. Chief executives must, in their respective portion of the public sector, designate a senior officer to be responsible for receiving any information a public servant believes reveals that a wrongdoing has been committed or that the public servant has been asked to commit a wrongdoing. A public servant may also provide such information to his or her supervisor. The PSDPA requires the Treasury Board to establish a code of conduct applicable to the federal public sector. It also provides that every chief executive of a department or federal body must establish internal procedures, including designating a senior officer to be responsible for receiving and dealing with disclosures of wrongdoing. This procedure should protect the identity of the persons involved and the confidentiality of the information collected in relation to disclosures and investigations. Chief executives of federal departments and agencies are responsible for ensuring that the Values and Ethics Code for the Public Sector, a code of conduct and internal disclosure procedures are effectively implemented in their organization. They must also ensure that their code of conduct and internal disclosure procedures are regularly monitored and evaluated. The Commissioner’s Office’s decision-making guide reminds potential public servant whistleblowers that many internal resources are available to help them resolve problems in their organization, including senior officers for internal disclosure,[8] union representatives, staff relations advisors, ethics officers, human resources advisors, conflict management advisors, diversity coordinators, equity coordinators, health and wellness coordinators, and conflict of interest advisors. Representatives of federal departments spoke about an interdepartmental working group, the Internal Disclosure Working Group, which includes senior officers, Treasury Board Secretariat officials and officials from the Commissioner’s Office. The working group discusses issues relating to the internal disclosure process and shares guidance and best practices. The departmental representatives stated that the working group is also developing the tools necessary to manage disclosures in the best way possible.[9] Tom Devine, Legal Director, Government Accountability Project, appearing as an individual, argued that the protection provided in the internal process is essential, as over 90% of whistleblowers make their disclosure to their superior. However, according to Scott Chamberlain, Director of Labour Relations and General Counsel, Association of Canadian Financial Officers, the internal disclosure process in federal departments and agencies does not work and employees do not use it because they believe it is designed to contain problems, not resolve them. He said this is why wrongdoings are often revealed through the media or other avenues. He added that the internal process is dysfunctional because it is not independent and that only an independent external process could be effective. Mr. Devine also noted that the PSDPA does not cover disclosures made to co-workers, even though these “are necessary for the homework to make responsible disclosures, to law enforcement, to Parliament, to the public, or to the media.” Finally, Mr. Friday emphasized that the internal process is quite different from the external one and that, unlike for the external disclosure process, the PSDPA provides very little direction regarding the functioning of the internal process. In his view, this role was assigned to the employer, namely, the Treasury Board Secretariat. A. Risk of Conflicts of InterestThe Committee heard that federal department and agency executives could find themselves in a conflict of interest situation when they manage cases of wrongdoing. Anne Marie Smart, Chief Human Resources Officer, Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer, Treasury Board Secretariat, explained that, where wrongdoing is founded, chief executives of federal departments and agencies consider what disciplinary measures should be taken and sometimes hire a third party to help them with that task. When chief executives are in a conflict of interest situation, they can ask another person, such as the Public Service Integrity Commissioner, or another department to determine what measures should be taken. In response to a question from a Committee member, representatives of federal departments and agencies asserted that their obligation to report to their manager in cases of allegations of wrongdoings does not create conflicts of interest. For example, Ms. Glover stated that the system used by her department seems to work because each deputy minister is responsible for operations in his or her department and must correct any and all problems that arise there. Moreover, she said she has to prepare a report for each allegation of wrongdoing and that, if an allegation is founded, a disciplinary process is launched. While recognizing that the internal process is not as independent as the external one, Amipal Manchanda, Assistant Deputy Minister, Review Services, at the Department of National Defence, noted that the PSDPA nonetheless includes some provisions to ensure independence. For example, his duties do not involve any operational activity within his department, as the person responsible for investigations into wrongdoings cannot be connected with operations or any elements of wrongdoing within those operations. Line Lamothe, Acting Director General, Human Resources and Workplace Services, at the Department of Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada, said it is staff, not the deputy minister, who must take the necessary measures when wrongdoing is found to have occurred. Nonetheless, according to Mr. Friday, there is an “issue of the potential conflict” in the internal process. Replying to another question from a Committee member, Ms. Smart stated that, if the senior officers of federal departments and agencies responsible for disclosures were independent and reported separately to a chief investigator, “it would set up a clash between the authorities of deputy heads to manage people.” However, A.J. Brown, Professor, Griffith University, who testified as an Individual, argued that internal disclosure units in departments and agencies should operate with a certain degree of independence from management. B. Values and Ethics CodesSome officials from federal departments and agencies discussed the process surrounding the public service’s values and ethics codes. Ms. Smart noted that federal departments and agencies develop their own codes of conduct and must not only adopt them, but also carry out awareness campaigns with their employees. Mr. Trottier added that all federal departments and agencies write their values codes into the letters of offer for new public servants and these newcomers must read the code as soon as they are hired. In addition, he said values and ethics training is mandatory for all public servants, which makes the process quite robust in his view. Luc Bégin, Ombudsman and Executive Director, Ombudsman, Integrity and Resolution Office, at the Department of Health, explained that all Health Canada employees must, on their appointment, attest that they have read and understood the Department’s code of conduct when they sign their letter of employment. David Hutton, Senior Fellow, Centre for Free Expression, appearing as an Individual, reported that, five years after the PSDPA came into force, the Treasury Board Secretariat drafted a new code of conduct for the federal public service and each federal department and agency had to write its own code of conduct. Yet, in his view, many of the codes were rewritten “to criminalize whistle-blowing and to make it a firing offence to say anything negative about your department,[such that] all kinds of negative consequences would flow from that.” Allan Cutler, Allan Cutler Consulting, testifying as an individual, said that, even though the deputy ministers of federal organizations are designated as being accountable for establishing procedures and policies pursuant to the Federal Accountability Act as well as effective internal controls, there are no consequences if these requirements are not met. He believes this is a fundamental flaw in the PSDPA. C. Selected Examples of Departments and AgenciesThe Committee invited representatives from selected federal departments and agencies to appear during its study in order to better understand their internal disclosure processes. Indigenous and Northern Affairs CanadaMs. Lamothe presented the internal disclosure process for Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada. She explained that it is managed by the senior officer, who is also the Director of the Centre for Integrity, Value and Conflict Resolution. Supported by three staff members, the senior officer is responsible for providing impartial advice and guidance to public servants who are considering making a disclosure of wrongdoing. The senior officer may hire the assistance of a subject matter expert to review the allegations and gather additional information. If the senior officer finds sufficient grounds to launch an investigation, he or she informs the deputy minister and asks for approval to launch an investigation. The Department then hires an independent investigator, and once the investigation is complete, the senior officer presents the findings and his or her recommendations to the deputy minister. She added that, since 2007, the department has received an average of three disclosures per year. Canada Border Services AgencyMr. Thibodeau explained that, to determine whether an investigation under the PSDPA is warranted, the immediate superior or the senior officer must address the following possibilities: “whether there is another recourse mechanism available to review the allegations; whether the matter, if proven to be founded, meets the act's definition of “wrongdoing” and the precedents set by the Integrity Commissioner; and, whether the issue is one of public or personal interest.” Where an investigation is not warranted, the employee receives the decision and an explanation in writing and is informed about the other recourse mechanisms available, such as the informal conflict resolution process. Communications Security EstablishmentJoanne Renaud, Director General, Audit, Evaluation and Ethics, Communications Security Establishment (CSE), explained that, for national security reasons, the CSE receives exceptional treatment under the PSDPA. However, its employees must have access to an internal mechanism for discussing or reporting serious ethical issues, including wrongdoings, that is vetted by the Treasury Board Secretariat. Ms. Renaud stated that CSE employees may make disclosures to their manager, a union representative, a labour relations official, the manager of the ethics office or her. As the Director General for Audit, Evaluation and Ethics, Ms. Renaud is responsible for receiving and reviewing allegations and subsequently establishing whether there are sufficient grounds for further action and whether resolution is appropriate. In addition, she must prepare an annual report to the Chief of the CSE setting out the number of disclosures received and investigations initiated, the recommendations made and any systemic issues identified. The Chief of the CSE is in turn responsible for reporting the disclosures made and related issues in his or her annual reports to the Minister of National Defence. In addition, the Committee learned that the CSE has multiple structures in place to meet the requirements of the PSDPA.[10] These include executive control and oversight, policy compliance teams in its operational areas, an on-site legal team from the Department of Justice and ongoing monitoring of internal processes. Moreover, all CSE activities are subject to scrutiny from the independent CSE Commissioner. Pursuant to the National Defence Act, the CSE Commissioner is responsible for undertaking any investigation he or she deems necessary in response to a complaint about the CSE. Finally, Ms. Renaud described the reprisal protections provided to CSE employees who make disclosures or co-operate with investigations into disclosures. Royal Canadian Mounted PoliceAccording to Mr. MacMillan the new code of conduct for members of the RCMP and the new code of conduct for RCMP public service employees “adopted a more positive, responsibilities-based approach to conduct, and both contain an obligation to report concerns relating to misconduct.” Since the PSDPA came into force, the RCMP has had three instances of founded wrongdoing. Under the RCMP’s PSDPA policy, the RCMP’s senior officer may form an assessment committee to confidentially review allegations of wrongdoings based on a list of assessment criteria. Unlike federal departments and agencies governed by the PSDPA, the RCMP has its own internal process for addressing reprisals, as it is the case for other internal RCMP processes, including the harassment and grievance processes. Department of National Defence and Canadian Armed ForcesMr. Manchanda explained that the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) internal whistleblower protection mechanism is very similar to that of the Department of National Defence, as every single component of the PSDPA is included in the CAF protection process. In addition, he said the definition of wrongdoing is very similar to that of the PSDPA and that the internal disclosure processes at the CAF and the Department are identical. Mr. Manchanda also noted that the Department of National Defence and the CAF share a values and ethics code and that an annual report on disclosure is prepared and submitted to the Treasury Board Secretariat’s Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer. Health CanadaMr. Bégin stated that Health Canada encourages its employees to report wrongdoing to their supervisor. He also told the Committee that Health Canada’s Ombudsman, Integrity and Resolution Office was created in February 2016 to provide confidential, neutral and independent ombudsperson, informal conflict resolution, and internal disclosure services as well as values and ethics’ training to public servants at Health Canada and the Public Health Agency of Canada. Mr. Bégin went on to inform the Committee about the measures the Ombudsman, Integrity and Resolution Office takes when a disclosure is founded. The Ombudsman Office reports its findings, any systemic problems that may give rise to wrongdoings and its recommendations for corrective measures to senior management. The reports are also posted on the Health Canada’s website. In response to a question from a Committee member, Mr. Bégin explained that when the Ombudsman Office receives a disclosure of wrongdoing, it contracts out the investigation to an independent firm. Public Services and Procurement CanadaAccording to Ms. Glover, PSPC has a strong framework to prevent and respond to possible wrongdoings, as it has embedded measures into its corporate culture, management practices, systems and processes. Additionally, PSPC has a procurement code of conduct for contractors. Ms. Glover added that, when allegations of wrongdoing are founded, disciplinary and corrective measures are taken and, when systemic issues are apparent, recommendations are made to remedy deficiencies in processes and procedures. However, she did not specify to whom these recommendations are made. Each year, PSPC receives between 25 and 30 complaints under the PSDPA.[11] Biagio Carrese, Director, Special Investigations Directorate, PSPC, stated that a team of 10 investigators with varying backgrounds, from criminal investigations to public procurement investigations, is dedicated to internal disclosures. 1.1.2.2 Other Resolution MechanismsSome witnesses described other resolution mechanisms available in federal departments and agencies that do not handle disclosures of wrongdoings, but rather other conflict situations such as harassment, toxic labour relations or grievances for other complaints, such as those relating to pay or the reimbursement of travel costs. For example, Mr. Trottier explained that the federal public service has a harassment grievance process, a harassment policy and a labour relations disciplinary policy. Mr. Bégin stated that, in his view, the problems raised through the internal disclosure process in many cases do not need to be investigated because they can be dealt with informally, including through labour relations or informal conflict management processes. Among the other resolution mechanisms at PSPC, Ms. Glover cited internal investigations; routine audits by the human resources, acquisitions and finance branches; and complaints relating to procurement. In addition, unions play a role in the disclosure of wrongdoings since, according to Mr. Yazbeck, they have a duty to represent members who have disclosed wrongdoings and they hire labour relations lawyers for difficult or complex cases. 1.1.2.3 Public Sector Integrity Commissioner and its Office

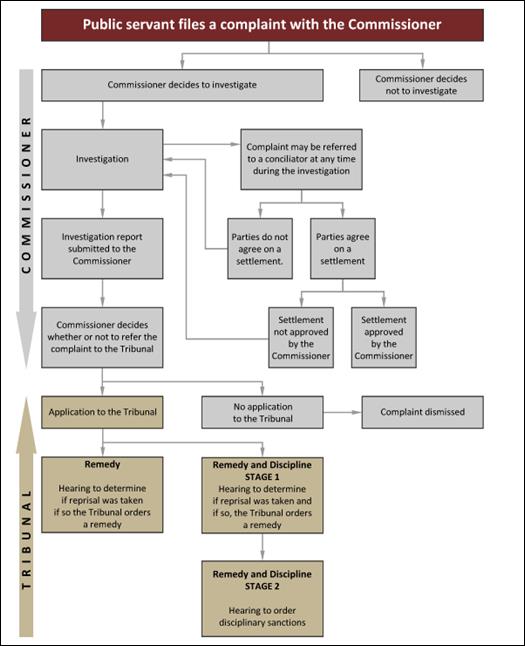

Section 39 of the PSDPA establishes the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner (the Commissioner), the second of two channels for the disclosure of wrongdoings in the federal public sector. The Commissioner is appointed by the Governor in Council with the approval of Parliament. Under section 13(1) of the PSDPA, a public servant can disclose wrongdoings directly to the Commissioner, without having to go through his supervisor or the senior officer designated by his chief executive. In addition, under section 33(1) of the Act, the Commissioner may begin a new investigation if a previous investigation or a person that is not a public servant provides information indicating that a wrongdoing has been committed. The Commissioner conducts investigations in order to bring “the existence of wrongdoings to the attention of chief executives and [makes] recommendations concerning corrective measures to be taken by them.”[12] The Commissioner holds all the powers of a commissioner under Part II of the Inquiries Act, in addition to those specifically granted by the PSDPA.[13] The Commissioner reports the results of investigations and provides information about the disclosures to chief executives, ministers, the Treasury Board, Parliament, or other relevant authorities depending on the circumstances and the nature of the information.[14] Thus, the Commissioner reports directly to Parliament and has the power to receive and investigate allegations of wrongdoing and reprisal complaints, to make recommendations to chief executives concerning corrective measures to be taken, and to review reports from chief executives following up on his or her recommendations. Under sections 38(3.1)–38(4) of the PSDPA, when an investigation leads to a finding of wrongdoing, the Commissioner must report it to the speakers of the Senate and the House of Commons within 60 days. This case report must include the finding of wrongdoing, any recommendations of the Commissioner to the chief executive of the portion of the public sector involved, and the comments of this chief executive. The Commissioner’s Office’s role is to establish a safe, independent and confidential process to enable public servants and members of the public to disclose potential wrongdoing in the federal public sector. The Commissioner’s Office’s jurisdiction extends to the entire federal public sector, including separate agencies and Crown corporations, which represents approximately 375,000 public servants.[15] For fiscal year 2017–2018, the Commissioner’s Office plans to spend a little more than $5.4 million under the 2017–2018 Main Estimates and to have 23 full-time equivalent employees.[16] The Commissioner’s Office’s disclosure procedure comprises three steps:

The Commissioner’s Office subsequently reviews the disclosure and determines the next steps. The public servant whistleblower must respect the confidentiality of the process. If reprisal actions are taken against the public servant whistleblower, he or she may file a complaint with the Commissioner’s Office, which must decide whether to investigate within 15 days. The case is referred to the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Tribunal if the Commissioner “has reasonable grounds to believe that reprisals occurred.”[19] In fiscal year 2015–2016, the Commissioner’s Office received 86 new disclosures of wrongdoing and 30 new reprisal complaints. It should be noted that these complaints are different from those received by public sector organizations and compiled in the Annual Report on the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act published by the Treasury Board Secretariat. As shown in Table 2, the number of new disclosures and complaints made to the Commissioner’s Office has remained relatively stable over the last three years. Table 2 – Statistics on disclosures to the Commissioner’s Office of the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner of Canada, Fiscal Years 2011–2012 to 2015–2016

Sources: Table prepared using data from the Office of the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner of Canada, 2011–2012 Annual Report, p. 8; 2012–13 Annual Report, p. 8; 2013–14 Annual Report, p. 9; 2014–15 Annual Report, p. 9; and 2015–16 Annual Report, p. 12. Since 2007, the Commissioner’s Office is responsible to investigate disclosures of wrongdoing and all reprisal complaints related to a protected disclosure. Some witnesses, such as Mr. Brown, suggested that the design of the dual roles of the Commissioner investigating disclosures and protecting whistleblowers place him in a situation of conflict of interest: “there’s a fundamental problem with the legislation in terms of the clarity and combination of roles of the Integrity Commissioner.” He suggested properly embedding in the legislation the whistleblower protection regime rather than relying on one body to “handle everything.” In addition, Mr. Yazbeck agreed that there can also be a problem with the commissioner’s role as the investigator of wrongdoing and the decision maker on whether wrongdoing occurred or not. Michael. Ferguson, Auditor General, Office of the Auditor General of Canada, brought to the Committee’s attention to the fact that his Office cannot investigate reprisal complaints from employees of the Commissioner’s Office. Joanna Gualtieri, Director, The Integrity Principle, who testified as an individual, went on to say that, since its budget is not allocated in an independent fashion, the Commissioner’s Office “is entirely dependent on government, more specifically Treasury Board.” In the same vein, Mr. Hutton said the Commissioner, as an officer of Parliament, is “supposed to be completely independent of the bureaucracy, but he's not.” In his view, one problem with the investigation process used by the Commissioner’s Office is its frequent reliance on external service providers. Finally, concerning resources, Mr. Brown believes it is essential for the Commissioner’s Office to have the resources it needs to fulfil its role. 1.1.2.4 Public DisclosuresSection 16(1) allows a public servant to make a disclosure to the public under certain conditions. First the public servant must have the right to make a disclosure either externally to the Commissioner’s Office or internally to his or her supervisor or senior officer. Second, there must also be no sufficient time to make a disclosure through the aforementioned disclosure mechanisms. Lastly, the public servant must believe on reasonable grounds that the subject matter of the disclosure is an act or omission that either constitutes a serious offence under Canadian law or constitutes an imminent risk of a substantial and specific danger to people or the environment. Section 16(1.1) creates an exception to section 16(1) and prohibits the disclosure to the public of information subject to any restriction created by an Act of Parliament. However, section 16(2) stipulates that if a different legislation provides a public servant the right to make a disclosure, that disclosure will not be limited by conditions under section 16(1). Concerning public disclosures, Mr. Radford noted that whistleblowing to the media likely implies “hardship” for the whistleblower because they are often not protected from reprisals, as was the case before the PSDPA came into force. Essentially, as explained by Mr. Rousseau, unless the public servants meet the “exceptional requirements” defined in section 16 of the Act, if they suffer from reprisals, they are not protected because their disclosure of wrongdoing was not a “protected disclosure” under the Act. In an attempt to provide context to public disclosures, Ms. Gualtieri, voiced that: Most of the whistle-blowers I've talked to, especially when you're talking about systemic wrongdoing … spend a tremendous amount of effort trying to effect corrective action and be heard inside the organization. I did it for six years, right up to the minister's office. Going to the media was not something that I relished. I had no experience in it, but what were my options? Going to the media was the last step …Whistle-blowers do not run to the media.… Also, I think we have to remember that the media historically has been the channel or the avenue by which we, the public, and you, the politicians, have been informed about systemic wrongdoing. 1.1.3 Am I Protected?Throughout the course of the study, the Committee was told that victims of reprisals may not be protected under the PSDPA if their disclosure of wrongdoing was not made following the prescribed guidelines of the Act. Generally, a “protected disclosure” under the Act is defined as a disclosure of wrongdoing, as defined by the Act, made in good faith by a public servant directly to their organization’s designated officer, to their supervisor or to the Commissioner. On this topic, Mr. Radford explained that in accordance with the PSDPA, “all persons who have made a protected disclosure are protected [from reprisals], whether or not their [allegation] of wrongdoing is founded, whether or not their claim of wrongdoing even has merit.” Mr. Cutler recounted numerous failures of the Act to protect employees within the public service, including private contractors. He spoke of an apparent “lack of willingness” of the Commissioner’s Office to investigate certain disclosures and reprisal complaints. For example, he raised the issue of an employee’s reprisal complaint – in the form of termination of employment – that was rejected because he or she was no longer a public servant. In brief, it is the opinion of many witnesses, including Mr. Cutler, that the act “completely fails to protect those it's [supposed] to protect. It's designed to protect senior bureaucrats, not the ordinary public servant.” That said, section 11 of the PSDPA includes confidentiality requirements to ensure the protection of whistleblowers. Chief executives must take measures necessary to protect the identity of persons involved in the disclosure process – including witnesses and alleged wrongdoers – and the confidentiality of the information collected. Under section 22 of the PSDPA, the Commissioner holds the same responsibility towards the persons involved in the disclosure. According to Mr. Trottier, confidentiality is “one of the main tenets” of the Act; it ensures that disclosures of wrongdoing will be “treated with the appropriate degree of confidentiality” to guarantee whistleblowers’ protection. Conversely, a large number of witnesses, including Mr. Hutton, claimed that the “strict confidentiality” protection is “completely bogus.” He explained that often, only a small number of people have access to the information disclosed in which case it is relatively easy to identify the whistleblower, especially if they were asking questions during the preliminary work necessary to make a disclosure. In Isabelle Roy’s, General Counsel, Legal Affairs, Professional Institute of the Public Service of Canada, own words: “Anonymity often can’t be protected.… There may be an attempt to keep the informer's identity confidential, but it's often impossible, despite people's best efforts and intentions.” 1.1.3.1 Access to Legal AdvicePursuant to section 22(a) of the PSDPA, it is the Commissioner’s duty to provide information and advice regarding the making of a disclosure of wrongdoing. However, the Commissioner has the power to authorize free access to legal advice of $1,500, and in exceptional circumstances of $3,000, for public sector employees who are considering making a disclosure of wrongdoing, serving as a witness or alleging a reprisal.[20] Mr. Friday recognized that as an “independent, neutral, objective, investigative decision-making body,” the Commissioner’s Office “may not be necessarily perceived as the right body to provide advice.” Thus, the Commissioner “make[s] the distinction between advice and information.” It can be difficult for a public servant to know how to proceed when they believe wrongdoing may be occurring in the workplace.[21] Notwithstanding those difficulties, Mr. Brown indicated that “the entitlement to legal aid” in the Canadian legislation is a good precedent and should be preserved. 1.1.4 Investigations of Wrongdoing1.1.4.1 Commissioner’s Duty and Investigative PowersSection 26 of the PSDPA identifies the purpose of investigations under the Act as that to bring the existence of wrongdoing to the attention of chief executives and to make recommendations concerning corrective measures to be taken by them. Investigations are also to be conducted as informally and expeditiously as possible. Concerning the entire process of disclosures and investigations of wrongdoing under the Act, the Commissioner, according to section 22 must:

However, according to section 23, the Commissioner cannot deal with a disclosure or begin an investigation when a person or body – acting under federal legislation other than the PSDPA – is dealing with the subject matter of the disclosure or the investigation, providing that this person or body does not do so as a law enforcement authority. Moreover, according to section 30(1) of the Act, the investigation powers of the Commissioner (sections 28 and 29 of the PSDPA) do not extend to information that is subject to solicitor-client privilege. Lastly, the Commissioner cannot use a confidence of the Queen’s Privy Council for Canada disclosed in violation of section 13(2) of the Act. The Commissioner can issue a subpoena or summon an individual in the exercise of his or her powers. However, the Commissioner must, under subsection 29(3), before entering the premises of any portion of the public sector in the exercise of his aforementioned powers, notify the chief executive of that portion of the public sector. Under the Act, chief executives must provide public access to some information related to the wrongdoing in the course of an investigation, subject to restrictions created by other federal legislation.[22] To tend to its responsibilities, the Commissioner’s Office performs an admissibility analysis and investigates both disclosures of alleged wrongdoing and reprisal complaints. According to Raynald Lampron, Director of Operations, Commissioner’s Office, since 2011, the Commissioner’s Office has investigated approximately 25% of the submitted disclosures of wrongdoing because “there [was] a valid reason not to deal with the disclosure” in 47% of cases and 3% of cases of disclosures of wrongdoing were not deemed sufficiently important by the Commissioner’s Office. Since 2013, Mr. Lampron reports that the Commissioner has not refused to investigate a disclosure because of the delay criteria of subsection 24(1)d). As such, 11 case reports of founded wrongdoing were tabled before Parliament from 15 April 2007 to 10 February 2017, which stemmed from the receipt of 774 disclosures and the launch of 110 investigations. The Commissioner has tabled two reports of founded wrongdoings since then. Mr. Radford noted that not one decision of the Commissioner pertaining to the 13 cases of founded wrongdoing, either in admissibility analysis or investigation, was overturned by a federal court or federal court of appeal. However, Mr. Rousseau added that, when wrongdoing is founded, the Commissioner cannot order corrective action, sanction the wrongdoers, launch criminal proceedings or seek injunctions to put an end to ongoing misconduct. Mr. Yazbeck stated that, even though the federal government has decades of case law on the process for investigating complaints and referring them to the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal under the Canadian Human Rights Act, the investigation process used by the Commissioner’s Office “is flawed,” “lacks thoroughness,” “view[s] whistle-blowers with suspicion,” is often “procedurally unfair,” has “a tendency to find ways not to deal with a complaint or dismiss it” and fails to take “a contextual or a subtle approach.” A. Investigation Time FramesUnder the Act, there are no provisions concerning the time frame the Commissioner can and should take to complete the admissibility analysis or investigations of disclosures under the Act. Nevertheless, Mr. Friday said the Commissioner’s Office has established service standards for processing cases. It aims to finish an initial case analysis within 90 days and complete an investigation within one year in 80% of cases. He reported that, to date, the Commissioner’s Office has met its service standards over 90% of the time. In cases where those norms were not respected, such as in the case of Don Garrett, a contractor whistleblower that was exposed to asbestos during the course of his work for the federal government, the investigation process “turned out to be a nightmare”. Mr. Friday expressed that part of the challenge for his Office is to ensure that they have the resources and service standards necessary to prevent delays. The work of his Office is substantial as certain cases may have 20 or 30 witnesses, some of them unavailable and others seeking legal representation. All these factors contribute to the delays. Nonetheless, his Office also has three staff members meet every three weeks to review files to identify and manage delays appropriately. According to Ms. Gualtieri, “it is naive to believe that an office like [the Commissioner’s] has the power, independence, and resources to take on cases of monumental impact and embarrassment to government. By definition, it is not a failing of the commissioner, but of the structure of the commission itself.” Furthermore, according to Ms. Daviau, the lack of resources at the Commissioner’s Office has led the organization to outsource certain investigations and creates an accountability loophole in which the rules, regulations and guidelines of the government do not apply to contracted investigators. B. Commissioner’s JurisdictionAlthough certain provisions under the Act apply to contractors of the federal government, according to Section 34 of the Act, if the Commissioner is of the opinion that a matter under investigation would involve obtaining information that is outside the public sector, he or she must cease that part of the investigation. Mr. Friday admits that this section has interfered with his ability to complete an investigation in the past, but that such a situation rarely happens. His Office has interpreted the Act as allowing them to ask for information from the private sector, but not demand it, although he would prefer to have the authority to request it under law. In the public sector, the Commissioner has the authority to demand access to information and facilities, although he must first notify the appropriate chief executive. According to Mr. Cutler, it is a problem that the Commissioner’s Office informs federal departments and agencies before he or she visits their offices to consult documents concerning investigations into disclosures because managers could destroy evidence in the meantime. Questioned about the possibility of evidence going missing or being destroyed, Mr. Friday responded that he does not believe that there is an issue with the notification requirement and sustains that it has so far never proven “deleterious” to an investigation. C. Commissioner’s Discretionary AuthoritiesVarious sections under the Act provide the Commissioner with the discretionary power to refuse to investigate a disclosure of wrongdoing. According to section 24(1), the Commissioner may refuse to commence or continue an investigation if he or she is of the opinion that:

Section 23(1) also precludes the Commissioner from investigating a disclosure of wrongdoing (under section 33) if a person or body acting under another Act of Parliament is dealing with the subject matter of the disclosure or the investigation other than a law enforcement authority. Mr. Radford notes that this section only prevents the Commissioner from duplicating a wrongdoing investigation, but not a reprisal one, and he added that even if an investigation has been dismissed, the public servant is always protected against reprisals. Mr. Radford said that the Commissioner’s Office accepts investigations of systemic harassment situations. For example, if a senior management bullies an entire unit or office. In such a case, the Commissioner’s Office would potentially consider the case as meeting the definition of wrongdoing in matters of gross mismanagement or a serious breach of the code of conduct. However, if a public servant presents a single situation of harassment, the Commissioner’s Office will generally encourage them to file a complaint under the harassment policy. Because a large number of disclosures are dismissed at the admissibility analysis stage, Mr. Devine supported that “whistle-blowers have a toothless investigative agency … that has a blank cheque not to ‘deal with’ complainants' cases or their rights, that has immunity for its actions, and that operates in total secrecy.” In the opinion of Ms. Daviau, “the Commissioner’s investigation processes are often unfair, lacking in thoroughness, and insensitive to whistle-blowers.” Mr. Rousseau testified, based on his experience defending whistleblowers that the investigative processes should be “fair and much more transparent.” Mr. Devine said the fact that the Commissioner’s Office has immunity for its actions and “operates in total secrecy” contradicts the PSDPA’s aim to improve transparency. He added that there is no limit on the Commissioner’s discretion and that, unlike his American counterpart, the Commissioner has no obligation to help whistleblowers. Mr. Rousseau argued that the Commissioner can “refuse to deal with any disclosure if the commissioner believes that the whistle-blower is not acting in good faith, or it is not in the public interest, or for any other valid reason.” 1.1.4.2 Auditor General of CanadaPursuant to section 14 of the PSDPA, federal public servants may disclose wrongdoings that concern the Commissioner’s Office to the Office to the Auditor General of Canada. The latter has the same powers and immunities as the Commissioner for dealing with disclosures. According to Mr. Brown, it is important for the Auditor General of Canada to play a role in protecting public servant whistleblowers. Mr. Ferguson noted that, under the PSDPA, he cannot investigate complaints of reprisals from employees of the Commissioner’s Office or seek information from outside the public sector. 1.1.5 Corrective MeasuresUnder section 9 of the PSDPA, a public servant is subject to appropriate disciplinary action in addition to, and apart from, any penalty provided for by law, including termination of employment, if he or she commits a wrongdoing. A wide range of disciplinary actions can be taken although Mr. Trottier admitted it may be limited to a simple reprimand. Ms. Stevens communicated that notwithstanding the provisions of section 9, corrective measures can be taken without a finding of wrongdoing. These corrective measures would update processes to ensure a problem does not occur again. At other times, however, Mr. Trottier sustained that corrective measures were not necessary, for example, when “the employee or the manager is gone; the situation has self-corrected.” Other examples may include misunderstandings or the natural termination of a contract. One of the main shortcomings identified in the context of corrective measures is that the Commissioner can only make recommendations on the appropriate corrective measure to be taken, based on his investigation, such that the deputy head, as explained by Ms. Smart, has to begin a completely new investigation into the wrongdoing to then order corrective measures. With regard to the internal investigations of wrongdoing, Ms Smart suggested that the legislation may lack direction and that it could compromise the appropriateness of corrective measures taken. However, she insisted that appropriate corrective measures would not be deterred by potential conflicts of interest since a third party can be hired in such instances. For his part, Mr. Rousseau suggested that the Act “does not ensure corrective action to end wrongdoing.” He then argued that the Commissioner’s inability to “order corrective action, sanction wrongdoers, initiate criminal proceedings or apply an injunction to halt ongoing misconduct” is a serious gap in the current legislation. 1.2 Solutions Proposed by Witnesses1.2.1 Expand the Definition of the Term ‘Wrongdoing’According to the International Best Practices for Whistleblower Policies, developed by Mr. Devine, the second best practice is the “subject matter for free speech rights with ‘no loopholes’.” In his opinion, whistleblower rights should cover all and any type of illegality, gross waste, mismanagement, abuse of authority, substantial and specific danger to public health or safety as well as any other activity or information that would undermine the mission of the organization to the public and its stakeholders. This definition would permit early protection and identification of wrongdoing or potential wrongdoing. Anna Myers, Director, Whistleblowing International Network, testifying as an individual, supports that this would create a safe alternative to silence. In response to a Committee member’s question, Mr. Devine, Mr. Devitt and Mr. Worth all explained that nearly all foreign whistleblower protection laws exclude personal injustices. For example, the Irish legislation excludes disclosures that are directly related to the employee’s contract of employment to ensure that personal grievances are not mixed with public interest disclosures. 1.2.2 Increase the Number of Protected Disclosure AvenuesAccording to the International Best Practices for Whistleblower Policies, the first best practice is the “context for free expression rights with ‘no loopholes’.” This provision entails that any disclosure which identifies significant misconduct or that would assist in carrying out legitimate compliance functions should be protected. Mr. Devine criticized loopholes in the legislation for “form, context, time or audience.” He also notes that disclosures in the workplace are always protected as retaliation often takes place in response to “duty speech” when a public servant may have only disclosed his suspicions to a co-worker. He qualified the requirements of the Act as “arbitrary restrictions” at odds with international best practices and claimed that they create a disincentive for whistleblowers to come forward. Other witnesses such as Mr. Worth and Duff Conacher, Co-Founder of Democracy Watch, likewise maintained that multiple disclosure channels should be available. A protected disclosure, according to Mr. Brown, should include [a]ny direct disclosures to a regulator or an integrity agency [and] should be automatically protected, whether they've gone internally or not. Disclosures to third parties, whether they're unions, civil society organizations, or the media, should be protected in any circumstances where either those internal or regulatory disclosures were not adequately dealt with and there are reasonable grounds for concluding that after a reasonable time, or where the court or tribunal can be reasonably satisfied that there was no safe mechanism, either internally or to the regulator, for somebody to disclose. He went on to say that, “[i]f a person has reasonable concerns that there was no safe way to disclose internally or to a regulator, that person should be entitled to a public-interest defence if he or she is prosecuted for a breach of confidence or any other remedy.” 1.2.2.1 An Accountable Internal Disclosure MechanismMr. Friday proposed amending section 12 of the PSDPA to expand the definition of “supervisor” to include any supervisor in the reporting line, up to and including the deputy minister, and the manager responsible for the subject of the disclosure. He believes that such an amendment would increase employee trust while making the process less constraining. However, Mr. Devine suggested that this proposal is still too restrictive since, before making a disclosure, public servants must research the matter to ensure their allegations are credible and may therefore suffer reprisals even before they can make a protected disclosure to a supervisor. In addition, Ms. Smart argued that making a protected disclosure should be as simple as possible for the public servant. Additionally, Mr. Radford assured the Committee that the Commissioner’s Office tries as much as possible “to help people who have made a protected disclosure by using the broadest possible definition of ‘protected disclosure.’” Some witnesses pointed out that, to avoid conflicts of interest, the internal disclosure units of federal departments and agencies must report to an external oversight body such as the Commissioner’s Office.[23] Mr. Brown specified that the latter would be responsible for not only compiling statistics, but also assessing situations and intervening if necessary. He believes that, as a result, the Commissioner’s Office would be more proactive, rather than reactive as it is today. Moreover, Mr. Brown contended that the whistleblower protection system should be embedded in both the governance of the Commissioner’s Office and the integrity systems of federal departments and agencies. To acknowledge and recognize that whistleblowers may not be aware of the severity of the information they dispose of, he also suggested extending protection under the Act to public-interest disclosures made to the police, for example. 1.2.2.2 Clarifying Public Disclosure ProvisionsIn situations of conflict of interest and obstruction of justice, Mr. Devine argued that a whistleblower should have the right to address the public directly. In Ireland, for example, whistleblowers can address the media or Member of Parliament when the internal disclosure channel is compromised, according to Mr. Devitt. In such circumstances, Mr. Brown is also the of opinion that whistleblowers should be protected from reprisals even when they have not first made a disclosure internally and he added that the Canadian legislation is “deficient” in this regard. 1.2.3 A Merit-Based AppointmentMr. Cutler argued that the process for appointing the Commissioner must be revamped. Mr. Hutton agreed and suggested appointing a respected and experienced individual from the private sector rather than someone who has worked solely in the public sector, making the appointment process more open and transparent, as in the United States, and giving the Commissioner a very clear mandate to expose wrongdoing. Mr. Conacher proposed in his brief to the Committee that the person appointed as Commissioner must have legal experience and a record of enforcing whistleblower protection, ethics rules or similar accountability laws. He added that the appointment process should be merit-based, open, transparent and independent, and it should be controlled by an independent committee of individuals from outside government and politics chosen by all the political parties represented in Parliament. This committee would assess the candidates and submit to Cabinet a short list from which the Commissioner must be selected. This system is similar to that currently used to appoint provincial judges in Ontario. In his brief, Mr. Conacher also proposed forbidding the renewal of the Commissioner’s fixed term. He further suggested that the [C]ommissioner must be clearly designated as the trainer (including by issuing interpretation bulletins), investigator and enforcer of all government policies (other than the policies enforced by the Auditor General) and must be required to conduct training sessions, conduct regular random audits of compliance and to investigate whistleblower complaints about violations of these policies… During its study on the Main Estimates 2017-18, the Committee was informed by Chantal Maheu, Deputy Secretary to the Cabinet, Plans and Consultations, Privy Council Office, that [t]he government announced a new approach to ensure open and transparent merit-based selection processes for [Governor in Council] appointments, with greater access for Canadians. The new approach now applies to more than 1,500 positions, including heads, vice-chairs, members of agencies and boards, chairpersons, chief executives, and agents and officers of Parliament. Since the Commissioner is an agent of Parliament, these changes will apply to his or her nomination. 1.2.4 Repealing the Requirement of Good Faith

The vast majority of witnesses, including Mr. Brown, Mr. Yazbeck and the Commissioner’s Office, supported eliminating the subjective requirement of good faith imposed on a whistleblower making a protected disclosure under the PSDPA. The Commissioner, Mr. Friday, also claimed that he has never rejected a disclosure of wrongdoing on the basis of “bad faith” and finds it an unnecessary disincentive.[24] In lieu of this “outmoded” requirement, in the opinion of Mr. Devine, a reasonable belief test should be sufficient to prevent intentional false disclosures of wrongdoing, which are never protected. As such, Mr. Devitt proposed that as long as a person has reason to believe that what they are reporting is true, they should be protected. 1.2.5 Ensuring Effective ProtectionIn order to ensure the effective protection of whistleblowers and all parties involved in supporting the disclosure, such as expert witnesses and coworkers, the following suggestions were made to the Committee. Firstly, as explained previously, all witnesses, including Mr. Brown, were of the opinion that disclosures for which there is an honest and reasonable belief should be protected irrespectively of the accuracy of the allegations or the motivation of the whistleblower. In this endeavour, the Commissioner proposed in a written brief to the Committee to amend subsection 2(1), paragraph 19.3(1)(d), and paragraph 24(1)(c) of the PSDPA to remove the words “good faith.” Secondly, in Mr. Conacher’s view, the difficulty to access legal advice or any kind of procedural advice to make a protected disclosure suggests that an office or legal clinic, to which public servants and members of the public could, anonymously, seek advice and be protected by default, even before making the disclosure, is necessary. If no such office or legal clinic is available, Mr. Conacher suggested that funding for legal fees to the whistleblower be comprehensive. An alternative suggestion, from the Commissioner’s Office, is to grant the President of the Treasury Board greater flexibility with the maximum monetary limit for legal advice that can be provided to whistleblowers. Furthermore, the Commissioner’s Office also suggested to amend subsection 25.1(1)(e) of the Act so that former public servants may also receive funds for legal advice. Thirdly, it was suggested that a comprehensive disclosure system should maximize the number of disclosure avenues available to whistleblowers. Mr. Worth clarified that internal disclosures should be encouraged when it is reasonable and possible but insisted that if an employee has reason to be uncomfortable disclosing internally, then they should be able to make a disclosure directly to the Commissioner or a different oversight agency. In cases of extreme emergencies, including the threat that evidence may be destroyed; the employee should be entitled to address the public without first reporting internally or to the Commissioner. In such situations, Mr. Brown suggested that a whistleblower should have the right to a public-interest defence or different remedies if he or she is prosecuted for a breach of confidentiality. Finally, Mr. Conacher recommended in his brief that, when the Commissioner refers a whistleblower complaint about the violation of another law, regulation or policy for which a designated investigative and enforcement agency exists, the commissioner must be required to ensure that the agency investigates the complaint within 90 days, and if an investigation does not begin within this time frame [then] the commissioner must be required to investigate the complaint. 1.2.6 Improving Investigation ProcessesConcerning the matters of conflicts of interest in the midst of internal investigations mentioned by Mr. Chamberlain, it was suggested by Ms. Smart to include provisions in the Act to guide the internal investigation process and ensure it is effective in achieving the purposes of the Act. Mr. Ferguson noted that one of the solutions available to employees who have identified problems with a department or agency’s internal process is to file a complaint with the Commissioner’s Office. In its brief, the Public Service Alliance of Canada proposed making the investigation process used by the Commissioner’s Office more transparent and subject to Access to Information requests, and removing the Commissioner’s discretion to deny disclosures of wrongdoing without conducting an investigation. Mr. Brown said he supports a change to subsection 23(1) of the PSDPA, which prevents the Commissioner from taking up cases that another person or body is reviewing, calling it a retrograde provision. He added that, in other jurisdictions, commissioners have the discretionary authority to intervene as they see fit. Furthermore, he argued that, like numerous other whistleblower protection and oversight bodies around the world, the Commissioner’s Office is very reactive, responding only to disclosures and complaints received rather than being proactive. Yet, in his view, “[t]he only way the system will work is if the Integrity Commissioner or the oversight agency has a very active role in making sure that those systems and procedures at the agency level are in place, that they're working, and that the discretions being applied by CEOs and their staff are actually fair and reasonable.” According to Mr. Devine, the Commissioner’s Office should be able to conduct informal investigations “so that there's a legitimate channel for closure as an alternative to due process proceedings that many unemployed whistle-blowers can't afford.” Concerning the Commissioner’s investigative powers, many witnesses, such as Mr. Conacher, in a brief, suggested that the Commissioner should have punitive rights to ensure that wrongdoing ceases. Examples of such punitive powers include: