CIIT Committee Report

If you have any questions or comments regarding the accessibility of this publication, please contact us at accessible@parl.gc.ca.

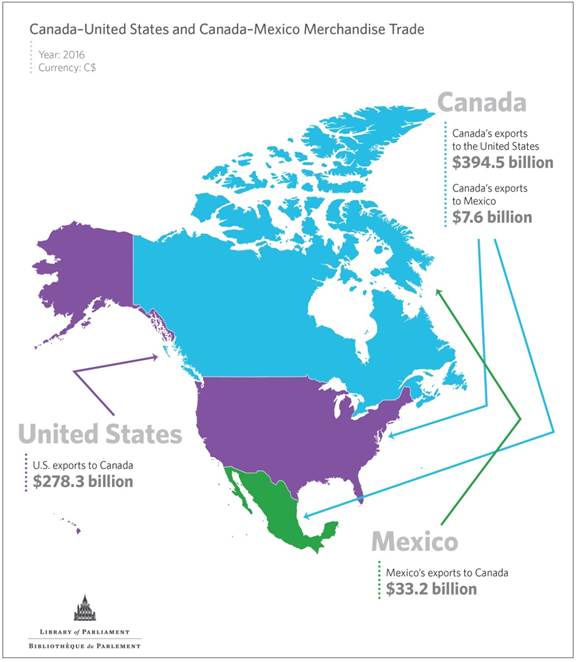

THE PRIORITIES OF CANADIAN STAKEHOLDERS HAVING AN INTEREST IN BILATERAL AND TRILATERAL TRADE BETWEEN CANADA, THE UNITED STATES AND MEXICOCHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCING THE STUDYMany would agree that trade liberalization among Canada, the United States and Mexico has resulted in an integrated, regional North American economy. In particular, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) – which entered into force on 1 January 1994 and superseded the Canada–United States Free Trade Agreement (CUSTA) – has enabled preferential market access among the three countries. It has also facilitated the development of cross-border value chains and production processes throughout the NAFTA region. In addressing economic, security and other challenges, Canada relies on close and productive relationships with both of its NAFTA partners. Its longstanding relationship with the United States, which is Canada’s largest trade and investment partner, has contributed to the economies of both countries. Statistics Canada estimates that, in 2013, the country’s exports to the United States accounted for 15.3% of Canadian gross domestic product and more than 2 million Canadian jobs.[1] A U.S. Department of Commerce report claims that U.S. exports of goods and services to Canada supported 1.6 million U.S. jobs in 2015.[2] In addition, more than 400,000 people cross the border between the two countries each day. Although geographically closer to the United States than to Mexico, Canada also has valuable relations with Mexico. The country was Canada’s third-largest merchandise trade partner in 2016, and Canadians made 1.9 million visits to Mexico in 2015, second only to the United States. Canada and Mexico have extensive consular networks, and collaborate in such fora as the United Nations, the Organization of American States, the G20, the Summit of the Americas and the North American Leaders’ Summit. Since January 2017, the United States has made various trade-related decisions that affect Canada, including in relation to NAFTA, the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and bilateral trade in softwood lumber. On 18 May 2017, the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) formally notified the U.S. Congress that the Trump administration intended to renegotiate NAFTA, and negotiating objectives were published on 17 July 2017. On 17 November 2017, the USTR released updated negotiating objectives. As of 20 November 2017, five rounds of negotiations had occurred. The United States has indicated the possibility of intent to withdraw from NAFTA. Recognizing the potential for significant changes to North America’s trade relationships, on 16 February 2017, the House of Commons Standing Committee on International Trade (the Committee) adopted a motion to undertake a study on the priorities of Canadian stakeholders having an interest in bilateral and trilateral trade in North America. Beginning on 4 May 2017, the Committee held 12 meetings in Ottawa, Ontario, during which it heard from: Canadian and U.S. businesses; academics; think tanks; groups representing organized labour and the interests of Indigenous peoples and women; and others. It also received a number of briefs and other submissions. As well, the Committee undertook fact-finding missions to the following U.S. cities: Seattle, Washington State; Sacramento, the Napa Valley, the San Francisco Bay Area and the Silicon Valley, California; Denver and Boulder, Colorado; Detroit, Michigan; Chicago, Illinois; Columbus, Ohio; Milwaukee, Wisconsin; and Washington, D.C. The fact-finding mission to Washington, D.C. included a meeting with members of the U.S. House of Representatives’ Ways and Means Committee’s Subcommittee on Trade. The report begins with statistical information about North American trade and investment, as well as general comments by witnesses about the North American trade relationship and raising Americans’ awareness about the importance of the Canada–U.S. trade relationship. It then summarizes the points made by individuals and groups with whom the Committee met in Ottawa and various U.S. cities on the following topics: negotiating free trade agreements (FTAs) and consulting Canadians; providing access to markets; moving goods, services and people; settling disputes; and expanding the scope of NAFTA. The report concludes with the Committee’s final thoughts and its recommendations to the Government of Canada. Most Canadian exports and imports of merchandise and services are sent to, or originate from, NAFTA countries. In addition, nearly one half of Canada’s stock of foreign direct investment is located in these countries, which are also the origin of almost one half of the stock of foreign direct investment in Canada.[3] The Committee’s witnesses described various aspects of North American trade, and commented on awareness among Americans of the Canada–U.S. trade relationship. A. North American Merchandise TradeThe United States is Canada’s most significant trade and investment partner. In 2016, Canada had a merchandise trade surplus with the United States; 76.3% of the value of Canada’s merchandise exports was destined for the United States, while 52.2% of the value of Canadian merchandise imports was from the United States. Figure 1 shows the value of Canada–U.S. merchandise trade since 1996. Figure 1 – Canada–U.S. Merchandise Trade, 1996–2016

Source: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament using Statistics Canada data accessed through Trade Data Online (database) on 26 September 2017. Canada’s trade and investment with Mexico is smaller than that with the United States, but has grown since the inception of NAFTA. In 2016, 1.5% of the value of Canada’s merchandise exports was destined for Mexico, while the country supplied 6.2% of the value of Canada’s merchandise imports; in that year, Canada had a merchandise trade deficit with Mexico. Figure 2 shows the value of Canada–Mexico merchandise trade since 1996. Figure 2 – Canada–Mexico Merchandise Trade, 1996–2016

Source: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament using Statistics Canada data accessed through Trade Data Online (database) on 26 September 2017.

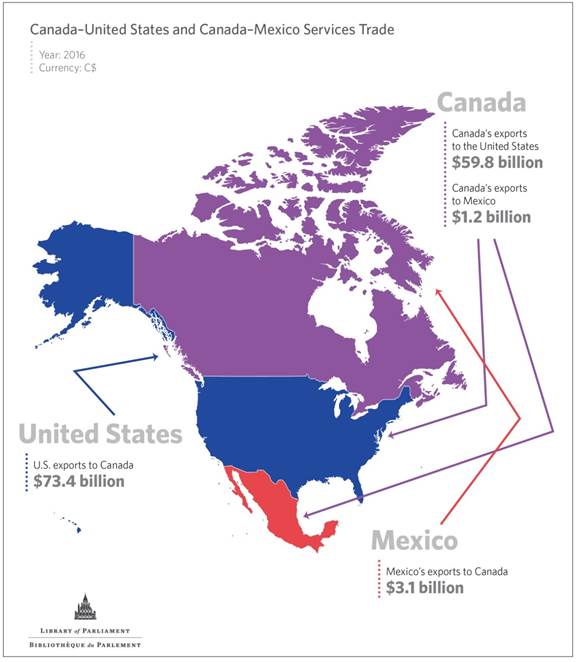

Source: Infographic prepared by the Library of Parliament using Statistics Canada data accessed through Trade Data Online on 26 September 2017. B. North American Services TradeCanada had a services trade deficit with the United States in 2016, as shown in Figure 3; the deficit was largely the result of trade in travel services, with Canadian travel services exports to, and imports from, the United States totalling $9.6 billion and $20.5 billion, respectively. In that year, Canada’s commercial services exports to, and imports from, the United States were valued at $41.7 billion and $43.1 billion, respectively; regarding transportation and government services, Canada’s exports to, and imports from, the United States were valued at $8.5 billion and $9.8 billion. In 2016, 54.9% of the value of Canadian services exports was destined for the United States, while the country was responsible for 55.5% of the value of Canada’s services imports. Figure 3 – Canada–U.S. Services Trade, 1996–2016

Source: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament using data from: Statistics Canada, “Table 376-0036: International Transactions in services, by selected countries, annual (dollars x 1,000,000),” CANSIM (database), accessed on 25 October 2017. Regarding Canada–Mexico trade in services, as shown in Figure 4, Canada had a deficit with Mexico in 2016; like the United States, this deficit was largely due to travel services. In 2016, Canadian travel services exports to, and imports from, Mexico were valued at $357 million and $2.5 billion, respectively. Canada’s commercial services exports to, and imports from, that country were $664 million and $425 million, respectively, in 2016; regarding transportation and government services, its exports to, and imports from, Mexico were $139 million and $263 million, respectively. In 2016, 1.1% of the value of Canada’s services exports was destined for Mexico, while the country was responsible for 2.4% of the value of Canada’s services imports. Figure 4 – Canada–Mexico Services Trade, 1996–2016

Source: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament using data from: Statistics Canada, “Table 376-0036: International transactions in services, by selected countries, annual (dollars x 1,000,000),” CANSIM (database), accessed on 25 October 2017.

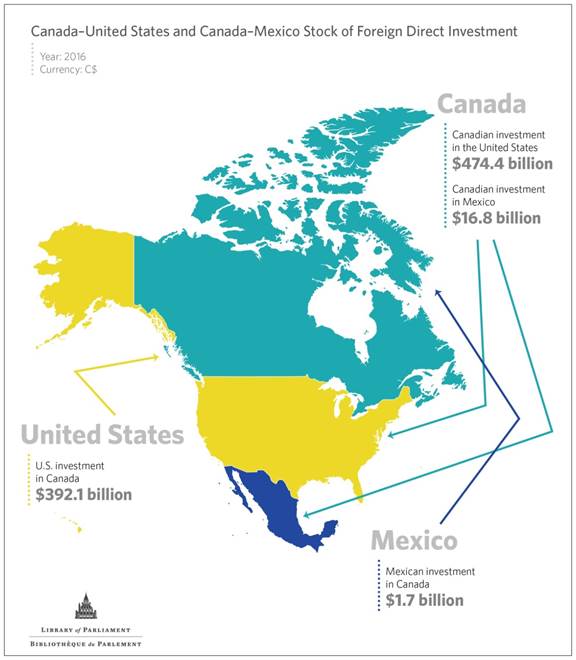

Source: Infographic prepared by the Library of Parliament using data from: Statistics Canada, “Table 376-0036: International transactions in services, by selected countries, annual (dollars x 1,000,000),” CANSIM (database), accessed on 25 October 2017. C. North American Foreign Direct InvestmentAmong the 120 countries for which data were available for 2016, the United States was the largest destination for Canadian direct investment abroad; it was also the largest source of foreign direct investment in Canada among the 55 countries for which data were available. In that year, 45.2% of the stock of Canada’s foreign direct investment was in the United States, while 47.5% of the stock of foreign direct investment in Canada was of U.S. origin. Figure 5 shows the two countries’ stock of foreign direct investment in each other since 1996. Figure 5 – Canada–U.S. Stock of Foreign Direct Investment 1996–2016

Source: Figure prepared by the Library of Parliament using data from: Statistics Canada, “Table 376-0051: International investment position, Canadian direct investment abroad and foreign direct investment in Canada, by country, annual (dollars x 1,000,000),” CANSIM (database), accessed on 26 September 2017. As well, among the 120 countries for which data were available for 2016, Mexico was the 10th largest destination for Canadian direct investment abroad; it was the 25th largest source of foreign direct investment in Canada among the 55 countries for which data were available. In that year, 1.6% of Canada’s stock of foreign direct investment was in Mexico, while 0.2% of the stock of foreign direct investment in Canada was of Mexican origin. Figure 6 shows the two countries’ stock of foreign direct investment in each other since 1996. Figure 6 – Canada–Mexico Stock of Foreign Direct Investment, 1996–2016