Chapter 12The Process of Debate

Motions

In order to bring a proposal before the House and obtain a decision on it, a motion is necessary.4 A motion is a proposal moved by one Member in accordance with well-established rules that the House do something, order something done or express an opinion with regard to some matter.5 A motion initiates a discussion and gives rise to the question to be decided by the House.6 This is the process followed by the House when transacting business.

While there may be many items on the Order Paper awaiting the consideration of the House, only one motion may be debated at any one time.7 Once a motion has been proposed to the House by the Chair, the House is formally seized of it. The motion may then be debated, amended, superseded, adopted, negatived or withdrawn.8

A motion is adopted if it receives the support of the majority of the Members present in the House at the time the decision on it is made. Every motion, once adopted, becomes either an order or a resolution of the House. Through its orders, the House approves bills at their various stages, regulates its proceedings or gives instructions to its Members or officers, or to its committees. A resolution of the House is a declaration of opinion or purpose;9 it does not require that any action be taken, nor is it binding. The House has frequently brought forth resolutions in order to show support for an action or outlook.10

A motion must be drafted in such a way that, should it be adopted by the House, “it may at once become the resolution … or order which it purports to be”.11 For example, it is usual for the text of a motion to begin with the word “That”. While examples may be found of motions with preambles, these are generally considered out of keeping with usual practice.12 It is customary for motions to be expressed in the affirmative. A motion should not contain any objectionable or irregular wording. It should neither be argumentative nor in the style of a speech.13

Debatable and Non-debatable Motions

Before 1913, the rules provided for a limited number of matters to be decided without debate; however, the general practice until then had been that all motions were debatable, barring the existence of some rule or practice to the contrary.14 In 1913, the Standing Orders were amended to specify that all motions were to be decided without debate or amendment unless specifically recognized as debatable in the rules.15 The Standing Orders therefore list the kinds of motions which are debatable and state that all others, unless otherwise provided for in the Standing Orders, are to be decided without debate or amendment.16

Debatable motions generally include:

- motions requiring written notice;

- all Orders of the Day, with the exception of concurrence in (but not consideration of) a ways and means motion;

- motions taken up during Routine Proceedings under the rubric “Motions”; and

- motions to adjourn the House for the purpose of initiating emergency debates.

As a general rule, every question that is debatable is amendable. Exceptions include motions to adjourn the House for the purpose of an emergency debate, to refer a government bill to a committee before second reading, and “That this question be now put” (the “previous question”).

Motions decided without debate or amendment tend to be concerned more with the ordering of business of the House or with the manner in which it is conducted than with the substance of that business. They include, but are not limited to, motions:

- that the House do now adjourn;

- to proceed to the Orders of the Day;

- that the House proceed to another order of business;

- that the debate be now adjourned;

- that the question be postponed to a specific day;17

- to go into a Committee of the Whole at the next sitting;

- that a Member be now heard; and

- to continue or extend a sitting.18

Classification of Motions

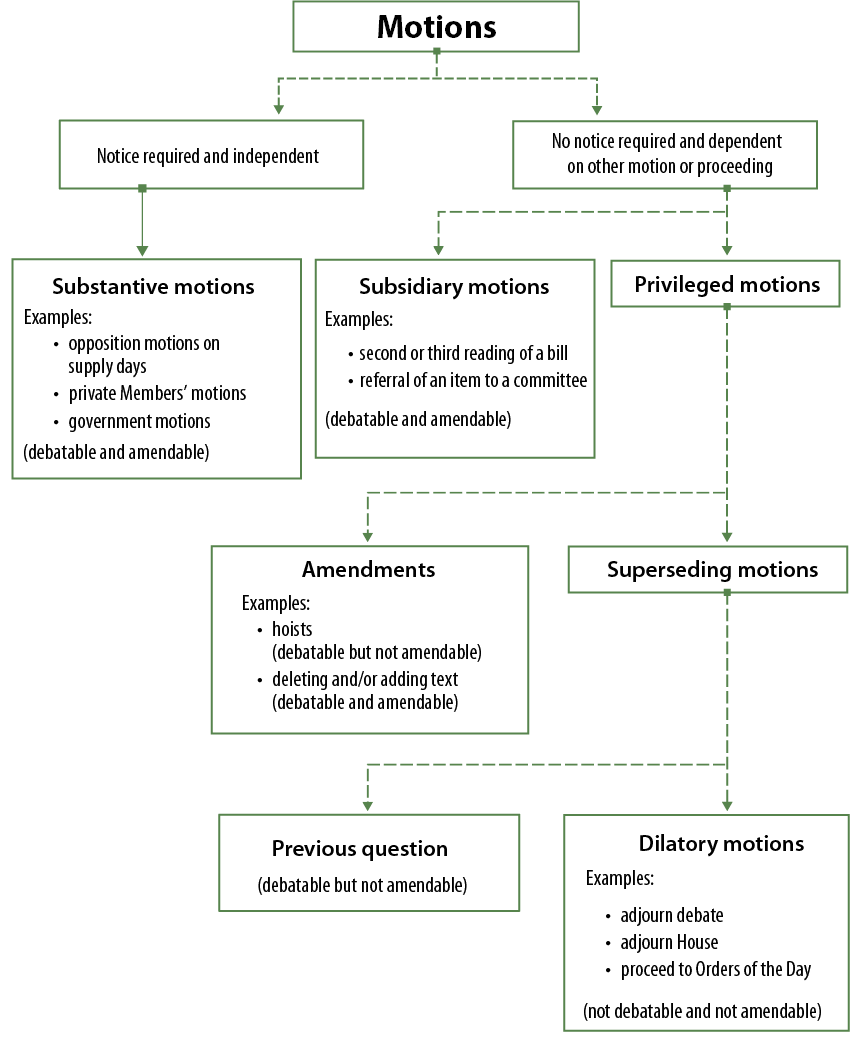

There is no single way of classifying motions.19 Generally, they may be grouped into those motions which are self-contained and require notice, and those which are dependent on some other proceeding or motion and do not require notice. Those in the first group are substantive motions and those in the second group are either subsidiary (ancillary) or privileged motions (see Figure 12.1, “Classification of Motions”).

Substantive Motions

Substantive motions are independent proposals which are complete in themselves, and are neither incidental to nor dependent upon any proceeding already before the House. As self-contained items of business for consideration and decision, each is used to elicit an opinion or action of the House. They are amendable and must be phrased in such a way as to enable the House to express agreement or disagreement with what is proposed. Such motions normally require written notice before they can be moved in the House. They include, for example, private Members’ motions, opposition motions on supply days and government motions.

Subsidiary Motions

Subsidiary motions, also known as ancillary motions, are procedural in nature; each is dependent on an existing order of the House and is used to move forward a question then before the House.20 For example, motions for the second and third readings of bills, and motions to commit (i.e., to refer a matter to a Committee of the Whole or to another committee) are subsidiary motions which are debatable and amendable.21 Like privileged motions, they may be moved without notice.22

Privileged Motions

A privileged motion (not to be confused with a motion arising from a question of privilege) differs from a substantive motion in that it arises from and is dependent upon the subject under debate. A privileged motion may be moved without notice when a debatable motion is before the House; the privileged motion then takes precedence over the original motion under debate. Privileged motions can either be amendments or superseding motions. Both types seek to set aside the question under consideration and may be moved only when that question is under debate.

Amendments

A motion in amendment arises out of debate and is proposed either to modify the original motion in order to make it more acceptable to the House or to present a different proposition as an alternative to the original. It requires no notice23 and is submitted in writing to the Chair.24 The provision that a motion must be in writing ensures that, if the motion is in order, it is proposed to the House exactly as worded by the mover. No amendment may be moved during the questions and comments period provided for after each Member’s speech on the main motion. After an amendment has been moved, seconded and evaluated as to its procedural acceptability, the Chair proposes it to the House.25 Debate on the main motion is set aside and the amendment is debated until it has been decided, whereupon debate resumes on the main motion (as amended or not) and other amendments may be proposed.

Just as the text of a main motion may be amended, an amendment may itself be amended. A subamendment is an amendment proposed to an amendment. In most cases, there is no limit to the number of amendments which may be moved; however, only one amendment and one subamendment may be before the House at any one time.26

An amendment must be relevant to the motion it seeks to amend. It must not stray from the main motion but must aim to refine its meaning and intent.27 An amendment should take the form of a motion to:

- leave out certain words in order to add other words;

- leave out certain words; or

- insert or add other words to the main motion.

An amendment should be so framed that, if agreed to, it will leave the main motion intelligible and internally consistent.28

An amendment is out of order, procedurally, if:

- it is irrelevant to the main motion29 (i.e., it deals with a matter foreign to the main motion, exceeds its scope,30 or introduces a new proposition which should properly be the subject of a separate substantive motion with notice31);

- it raises a question substantially the same as one which the House has decided in the same session or conflicts with an amendment already agreed to;32

- it is completely contrary to the main motion and would produce the same result as the defeat of the main motion;33

- any part of the amendment is out of order;34 or

- it originates with the mover of the main motion.35

When an amendment is being debated, its mover may not move an amendment to his or her own amendment. If the Member wishes to modify the amendment, he or she must seek the consent of the House to withdraw the original amendment and propose a new one.36

Amendments to certain items of business are subject to additional restrictions. For example, only one amendment and one subamendment may be moved to a motion proposed in the budget debate or to a motion proposed under an Order of the Day for the consideration of the Business of Supply on an allotted day. In the latter case, such an amendment (or subamendment) may be moved only with the consent of the motion’s sponsor, as is the case with private Members’ motions and motions for second reading of private Members’ bills.37 Further, a motion to refer a government bill to committee before second reading is not subject to amendment.38

Subamendments

Most of what applies to amendments applies equally to subamendments. Each subamendment must be strictly relevant to, and not at variance with the sense of, the corresponding amendment and must seek to modify the amendment and not the original question.39 A subamendment cannot enlarge upon the amendment, introduce new matters foreign to it or differ in substance from it.40 A subamendment cannot strike out all of the words in an amendment, thereby nullifying it; the Speaker has ruled that the proper course in such a case would be for the House to defeat the amendment.41 Debate on a subamendment is restricted to the words added to or omitted from the original motion by the amendment. Since subamendments cannot be further amended, a Member wishing to change one under debate must wait until it is defeated and then propose a new subamendment.

Superseding Motions

A superseding motion is one which is moved for the purpose of superseding (or replacing) the question before the House. There are two types of superseding motions: the previous question42 and several subtypes known collectively as dilatory motions. While the text of an amendment is dependent on that of the main motion, the text of a superseding motion is predetermined and the motion is proposed with the intention of setting aside further discussion of whatever question is before the House.

A superseding motion can be moved without notice when any other debatable motion is before the House. The Member moving a superseding motion can do so only after having been recognized by the Speaker in the course of debate. It is not in order for such a motion to be moved when the Member has been recognized on a point of order or during a period provided for questions and comments.43 With the exception of the previous question, superseding motions are not debatable and cannot be applied to one another.

The Previous Question

When debate on a motion concludes (i.e., no Member not already having done so wishes to speak, or the House has ordered debate to conclude), the question is put by the Chair, enabling the House to agree or disagree with the proposition before it. The act of putting the question assumes that the House has finished debate and wants to make a decision. Normally, this is implicit in the process, as seen when the Chair asks if the House is “ready for the question”; it can, however, be tested by asking the House to make a formal decision as to whether or not the question should be put. In such a case, a decision is required prior to the one on the main motion. This is achieved by proposing, “That this question be now put”, a motion known as the previous question.44

The motion, “That this question be now put”, has two uses:

- to supersede the question under debate since, if it is negatived, the Speaker is bound not to put the question on the main motion and the House proceeds to its next item of business; and

- to limit debate since, until it is decided, it precludes any amendment to the main motion.45 If it is adopted, it compels the House to proceed immediately to a decision on the main motion.46

The previous question has been used irregularly since Confederation. There are only four recorded instances of its use in the 19th century.47 In 1913, a noteworthy event occurred in relation to the previous question when the government, seeking means to bring an end to the lengthy debate on its Naval Aid Act, moved a motion introducing three new Standing Orders—including the closure rule—and then eliminated any possibility of amendment by moving the previous question immediately thereafter.48 The new rules were adopted after days of acrimonious debate49 and the immediate effect of this was the application of the closure rule to the debate on the Naval Aid Act.50 In the late 1920s, and afterwards in the 1940s and early 1950s, the previous question was used fairly regularly. Following an almost 19-year lapse in which it was not used at all,51 it came again into frequent use in the 1980s and 1990s and remains in regular use.52

The previous question has been applied to many substantive motions before the House. For example, it has been moved to the Address in Reply to the Speech from the Throne,53 to the various stages of a bill,54 to motions for concurrence in reports from committees,55 to motions of instruction to standing committees,56 and to motions sponsored by private Members57 and the government.58

The previous question cannot be proposed by the mover of the main motion, nor can it be moved by a Member who has been recognized on a point of order. It can be moved only by a Member recognized to speak in the regular course of debate. The previous question is a debatable superseding motion which is given priority once it is proposed during debate.59 The same time limits applicable to speeches and questions and comments during debate on the main motion apply to the debate on the previous question. It cannot be proposed while an amendment to the main motion is being considered but, once the amendment is disposed of by the House and debate resumes on the main motion itself, amended or not, the previous question can then be moved.60 While the previous question is debatable, it is not amendable61 and can be withdrawn only by unanimous consent.62 The previous question cannot be moved in a Committee of the Whole or in any committee of the House.63

A unique feature of the previous question is that it does nothing to hinder debate on the original motion.64 What is relevant to the previous question is also relevant to the original motion. Nonetheless, after the previous question has been moved, it constitutes a new question before the House and Members may participate in debate even if they have already spoken to the main motion or to any amendment which has been disposed of.65 Since the previous question is not a substantive motion, its mover is not granted the right to speak a second time in reply.66

Debate on the previous question may be superseded by a motion to adjourn the debate, a motion to adjourn the House or a motion to proceed to the Orders of the Day;67 however, such motions are not in order once the House has adopted the motion for the previous question.68 If debate on the previous question is adjourned or interrupted by the adjournment of the House or otherwise, debate on the previous question and the original motion ceases and both are retained on the Order Paper.69 In some of these cases, the main motion and previous question were again brought before the House and decided; in others, there was no further debate or decision and the motions lapsed when the session ended.70

When debate on the motion for the previous question has concluded, the question is put to the House.71 Members moving the previous question have, when a recorded division was held, voted in favour, against, or not at all.72 If the previous question is resolved in the affirmative, the Chair immediately, without further debate or amendment, puts the question on the main motion.73 If it is negatived,74 resolving that the question be not now put, the Speaker must not put the question on the main motion at that time; the main motion having been superseded, the House proceeds to its next item of business, and the main motion is removed from the Order Paper.

A recorded division on the previous question may be deferred.75 However, when a deferred division on the previous question is held and the motion is adopted, the question is put immediately on the main motion and the latter vote cannot be further deferred, except on a Friday, unless by special order or by the Chief Government Whip, with the agreement of the Whips of all other recognized parties.76

Dilatory Motions

Dilatory motions are superseding motions intended to dispose of the original question before the House either for the time being or permanently. Although dilatory motions are often moved for the express purpose of causing delay, they may also be used to advance the business of the House. Thus, dilatory motions are used both by the government and the opposition.

Dilatory motions can be moved only by a Member who has been recognized by the Chair in the regular course of debate and not on a point of order.77 Dilatory motions include motions:78

- to proceed to the Orders of the Day;

- to proceed to another order of business;

- to postpone consideration of a question until a later date;

- to adjourn the debate; and

- to adjourn the House.79

The Standing Orders indicate that dilatory motions are receivable “when a question is under debate”;80 however, they have also been moved when there was no question under debate during Routine Proceedings.81 The Chair has found in order motions that the House proceed to the next item under Routine Proceedings,82 and that the House proceed to the Orders of the Day.83 However, a motion to move to an item under Routine Proceedings, other than the next one in the sequence, was ruled out of order on the grounds that the House should proceed from item to item in the usual order.84 Unlike the previous question, dilatory motions may be proposed while an amendment to a motion is under debate.85

When a dilatory motion is moved and seconded, the Chair must be provided with its text in writing.86 Dilatory motions do not require notice, are not debatable or amendable, and, if in order, are put by the Chair immediately. Until 1913, dilatory motions were debatable and the consideration of the superseded question would be delayed by the debate and decision on the dilatory motion.87 When a dilatory motion is moved now, a recorded division is usually demanded and the bells are rung for a maximum of 30 minutes to summon the Members, thus delaying debate on other matters before the House. When a motion to adjourn the House is adopted, the time remaining in the sitting day is also lost.

A motion to proceed to the Orders of the Day or to proceed to another order of business, while categorized as a dilatory motion, is often used by the government during Routine Proceedings to counteract dilatory tactics or to advance the business of the House. A motion to proceed to the Orders of the Day, if adopted, supersedes whatever is then before the House and causes the House to proceed immediately to the Orders of the Day, skipping over any intervening matters on the agenda.88

Motions to Proceed to the Orders of the Day

The motion “That the House do now proceed to the Orders of the Day” may be moved by any Member prior to the calling of Orders of the Day; however, once the House has reached this point, moving the motion would be redundant.89 The Chair has ruled that a motion to proceed to the Orders of the Day is in order during Routine Proceedings90 which, in recent practice, is usually when it has been proposed.91 If the motion is adopted during Routine Proceedings, the item of Routine Proceedings then before the House (and all further items under Routine Proceedings) and requests for emergency debates are superseded and stood over until the next sitting and the House moves immediately to the Orders of the Day.92 No point of order may be entertained once the Speaker has put the question to the House.93 Furthermore, if a motion is being debated at the time a motion to proceed to the Orders of the Day is moved and adopted, it is dropped from the Order Paper. If the motion to proceed to the Orders of the Day is defeated, the House continues with the business before it at the time the motion was moved. This motion has been moved by both the government and the opposition either as a dilatory tactic or to counter dilatory tactics.94

Motions to Proceed to Another Order of Business

A motion “That the House proceed to (name of another order)”, if adopted, supersedes whatever business is then before the House. The House proceeds immediately to the consideration of the order named in the motion. If a motion to proceed to another order is defeated, debate on the main motion or question before the House continues.

When the House is considering Government Orders, a motion to proceed to another Government Order is not in order if moved by a private Member since it is the government’s prerogative to call its business in the sequence it wants.95 On one occasion during Government Orders, a motion was moved proposing that the House proceed to consider an item of Private Members’ Business. The Speaker ruled that, while the House may move from one item to another within the same type of order, a motion to move from one type of order (Government Orders, in the case at hand) to another in a different section of the Order Paper (Private Members’ Business, in this case) seeks to suspend the normal course of House business and, as such, is a substantive motion which could be moved only after due notice.96

A motion to proceed to another order has been interpreted to allow the House to move from one rubric or item of Routine Proceedings to the next in the sequence of items under Routine Proceedings, even though there may be no substantive motion before the House.97 Use of this motion has become obsolete outside of Routine Proceedings as the sequence of business during Government Orders and Private Members’ Business is now determined by various Standing Orders. The House tends to proceed by unanimous consent when it wishes to vary the order of business as set out in the rules.

Motions to Adjourn the Debate

The purpose of a motion to adjourn a debate is to set aside temporarily the consideration of a motion. It can be used as a dilatory tactic or for the management of the business of the House. If the House adopts a motion “That the debate be now adjourned”, then debate on the original motion stops and the House moves on to the next item of business. However, the original motion is not dropped from the Order Paper; it remains on the House agenda and is put over to the next sitting day when it may be taken up again. Thus, the adoption of a motion to adjourn the debate has the effect of delaying further debate on a motion on that day.98 If the motion to adjourn the debate is defeated, then debate on the original motion continues.

A motion to adjourn the debate is in order when moved by a Member who has been recognized by the Speaker to take part in debate on a question before the House.99 It may not be moved during Routine Proceedings, except during debate on motions moved under the rubric “Motions”. The mover of the motion being debated may not move to adjourn the debate since this would involve moving two motions simultaneously.100 In addition, the restrictions which apply to motions to adjourn the House also apply to motions to adjourn the debate.101

Motions to Adjourn the House

The Standing Orders provide for the House to adjourn every day at a specified time.102 However, a Member may move a motion “That the House do now adjourn” at some other time during the sitting. If the motion is agreed to, the House adjourns immediately until the next sitting day. With the exception of non-votable items of Private Members’ Business and motions for concurrence in committee reports, the motion under consideration by the House at the time is not dropped from the Order Paper, but is simply put over to the next sitting day when it may be taken up again.103

Motions to adjourn are referred to as dilatory motions when they are used to supersede and delay the proceedings of the House.104 However, motions to adjourn are not considered to be dilatory motions when they are used by the government for the management of the business of the House. A motion to adjourn the House may be proposed by the government simply to end a sitting.105 For example, this motion has been used by the government to adjourn late in the sitting but before the scheduled hour of adjournment, rather than call another item of business,106 or to adjourn because of extraordinary circumstances.107 A motion to adjourn the House is not debatable. The House has nonetheless used this motion, by unanimous consent or special order, as the vehicle for a debate on a matter deemed important but which was not necessarily connected to any business before the House.108 In addition, the motion to adjourn the House is debatable when used to hold an emergency debate109 or, at the end of a sitting, for the adjournment proceedings.110

A motion to adjourn the House is in order when moved by a Member who has been recognized by the Speaker to take part in debate on a motion before the House,111 or to take part in business under Routine Proceedings.112 A motion to adjourn the House is not in order if conditions are attached to the motion (e.g., where a specific time of adjournment is included) since this transforms it into a substantive motion which may be moved only after notice.113 In addition, a motion to adjourn the House may not be moved in the following circumstances:

- during Statements by Members or Question Period;114

- during the questions and comments period following a speech;115

- on a point of order;116

- by a Member moving a motion in the course of debate (the same Member cannot move two motions at the same time);

- during the election of the Speaker;117

- during emergency debates or the Adjournment Proceedings since, at these times, the House is already considering a motion to adjourn;118

- on the final allotted day of a supply period;119

- during debate on a motion that is subject to closure;120

- when a Standing Order or special order of the House provides for the completion of proceedings on any given business before the House121 except when moved by a Minister;122 or

- during proceedings on any motion proposed by a Minister in relation to a matter the government considers urgent.123

If a motion to adjourn is defeated, a second such motion may not be moved until some intermediate proceeding has taken place or item of business has been considered.124 Members may move repeatedly and alternately the motions to adjourn the debate and to adjourn the House, as these motions do not have the same effect and are considered intermediate proceedings.125

Motion that a Member Be Now Heard

While not strictly a dilatory motion, a motion, “That a Member be now heard” can be used as a dilatory tactic.126 Unlike dilatory motions, if adopted, it does not have the effect of superseding the original question; it merely determines who is to speak next on the motion under consideration. Such a motion can only be moved on a point of order and has been used in conjunction with dilatory motions.127

When two Members rise simultaneously to speak, the Speaker will recognize one of them. By rising on a point of order before the Member recognized has begun to speak, another Member may move that the Member who had not been recognized “be now heard”. If the Speaker judges the motion to be in order, the question is put forthwith without debate.128 If carried, the Member named in the motion may speak to the original motion but, if defeated, the Member originally recognized retains the right to speak.129